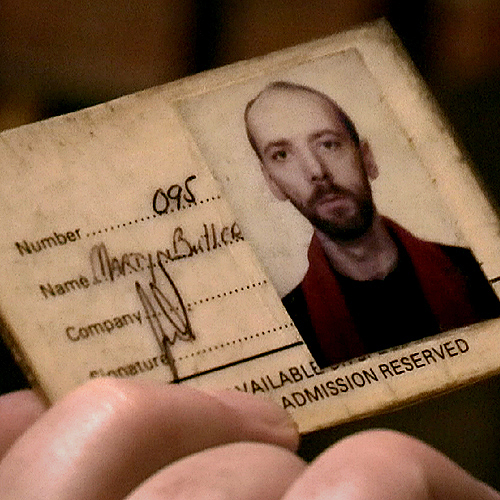

Callum changes into his uniform quickly. He stops and looks in the mirror - one last check.

He’s making sure there are no wires showing.

No tell-tale signs that he has just fixed a tiny camera and microphone in place.

The 21-year-old is about to start a 13-hour shift as a detainee custody officer at Brook House Immigration Removal Centre.

Many of his shifts begin this way, rigging up in the toilets after a workout in the on-site gym.

Callum is secretly filming the chaos, violence and distress he witnesses at the centre.

Distress such as the first suicide attempt he had to deal with.

He was one of the first officers on the scene when a Ghanaian man tried to hang himself from the top floor landing.

They managed to get the ligature off the man’s neck and he survived. But it took its toll.

“I went to bed that night and didn’t sleep - then the nightmares start to happen, replays in your mind,” says Callum.

“I was signed off with a stress-related disorder for about two-and-a-half weeks. When you know you are a cog in the machine that has made him feel that level of desperation, to know the impact you’re having on the lives of these people is difficult.”

Callum started working at Brook House, near Gatwick Airport, in West Sussex, two years ago.

His ambition is to become a professional football referee, but straight out of school, he needed a job.

The detention centre is run by G4S. The UK branch of this multi-national company is employed by the government to run two of the UK’s 11 immigration removal centres.

Callum was shocked by what he found there.

“It’s changed me from being a young, naive boy with not much understanding of human suffering into someone who witnessed it first hand, in probably some of the most horrific ways,” he says.

He decided to blow the whistle on what he describes as the “culture of violence” inside an institution that houses people waiting to be removed from the UK.

He found a failing system, where even those desperate to leave the country are frustrated by delays, while others appear to play the system.

It's a system that keeps some detainees locked up and in limbo for years, yet releases many others having made no clear decisions about their futures.

“The purpose of detention centres shall be to provide for the secure but humane accommodation of detained persons in a relaxed regime with as much freedom of movement and association as possible, consistent with maintaining a safe and secure environment, and to encourage and assist detained persons to make the most productive use of their time, whilst respecting in particular their dignity and the right to individual expression.”

Callum’s hidden camera soon picks up the reality of life in Brook House.

“It is just chaos,” he says.

“People abusing drugs, dealing drugs, self-harming, fighting. And the staff, they can’t cope, they can’t manage with what’s happening in the centre.”

Detainees in Brook House

It’s Callum’s job to get detainees involved in activities such as football, pool and table tennis.

“In reality, I basically fill in wherever I’m needed - whether it be in the wings, or on visits, or on reception,” he says.

When Callum walks into the detention centre, it feels like he's entering a prison. Cells holding two, or even three, men line the landings.

Many of the staff, he believes, are doing their best, but there can be huge pressure. The wings are often run with the minimum number of officers allowed by the Home Office.

“The general morale among officers is pretty poor. It’s often just two officers to each wing with more than 100 detainees,” he says.

“It affects the detainees massively because there’s just not enough staff to lock up a wing. As a result, things are rushed.”

This is meant to be a place of safety for both detainees and officers, but it doesn’t feel like it.

On one shift, Callum sees a detainee who has been slashed across the neck by another.

His attacker apparently lashed out because he hadn’t got the extra egg that he wanted for breakfast.

On another occasion, the officer is told that two colleagues had been taken to hospital after being attacked by a detainee wielding a broken pool cue.

Brook House detainees outside

But it is the number of people harming themselves that is particularly disturbing.

Callum’s hidden camera soon picks up the reality of life in Brook House.

“It is just chaos,” he says.

“People abusing drugs, dealing drugs, self-harming, fighting. And the staff they can’t cope, they can’t manage with what’s happening in the centre.”

Detainees in Brook House

It’s Callum’s job to get the men held at Brook House involved in activities such as football, pool and table tennis.

“In reality, I basically fill in wherever I’m needed - whether it be in the wings, or on visits, or on reception,” he says.

When Callum walks into the detention centre it feels like he is walking into a prison. Cells holding two, or even three, men, line the landings.

Many of the staff, he believes, are doing their best, but there can be huge pressure. The wings are often run with the minimum number of officers allowed by the Home Office.

“The general morale among officers is pretty poor. It’s often just two officers to each wing with more than 100 detainees,” he says.

“It affects the detainees massively because there’s just not enough staff to lock up a wing. As a result, things are rushed.”

This is meant to be a place of safety for both detainees and officers, but it doesn’t feel like it.

On one shift, Callum sees a detainee who has been slashed across the neck by another.

His attacker apparently lashed out because he hadn’t got the extra egg that he wanted for breakfast.

On another occasion, the officer is told that two colleagues had been taken to hospital after being attacked by a detainee wielding a broken pool cue.

Brook House detainees outside

But it is the number of people harming themselves that is particularly disturbing.

The 2016 annual report by the Independent Monitoring Board that oversees Brook House says many detainees arrive feeling depressed or suicidal - and incidents of self-harm and the threat of self-harm are frequent.

Nearly half of the detainees are foreign national offenders (FNOs), former prisoners who have reached the end of their sentences and are due to be deported.

The remainder are people from a wide range of backgrounds who, apart from immigration offences, may never have been in trouble.

They include people applying for asylum and others such as doctors and students, whose visas have run out.

“The contrast between the asylum seekers and the migrants to the hard-line criminals, they swarm like sharks around small fish,” says Callum.

“They will just get eaten alive, just snapped up like that.”

Alif Jan, who was a doctor in Pakistan, was detained at Brook House for eight days.

He moved to the UK 16 years ago and was a trainee audiologist until his student visa ran out.

“In Brook House you can be put with any criminal in the same room,” he says.

“Guys were fighting with each other. Banging their doors, screaming, shouting and swearing.

“And you can’t do anything, just stay inside your room.”

Officers in riot gear prepare to enter a room

Alif Jan has since been released while the Home Office considers his case. Looking back, he says the experience of Brook House can change people.

“If you are like a nice person, very cool-minded, you will become aggressive - because you are facing aggressive things most of the time.

“The behaviour of the guys there, and the behaviour of the staff there, these are the two worst things.”

The 2016 annual report by the Independent Monitoring Board that oversees Brook House says many detainees arrive feeling depressed or suicidal - and incidents of self-harm and the threat of self-harm are frequent.

Nearly half of the detainees are foreign national offenders (FNOs), former prisoners who have reached the end of their sentences and are due to be deported.

The remainder are people from a wide range of backgrounds who, apart from immigration offences, may never have been in trouble.

They include people applying for asylum and others such as doctors and students, whose visas have run out.

“The contrast between the asylum seekers and the migrants to the hard-line criminals, they swarm like sharks around small fish,” says Callum.

“They will just get eaten alive, just snapped up like that.”

Alif Jan, who was a doctor in Pakistan, was detained at Brook House for eight days.

He moved to the UK 16 years ago and was a trainee audiologist until his student visa ran out.

“In Brook House you can be put with any criminal in the same room,” he says.

“Guys were fighting with each other. Banging their doors, screaming, shouting and swearing.

“And you can’t do anything, just stay inside your room.”

Officers in riot gear prepare to enter a room

Alif Jan has since been released while the Home Office considers his case. Looking back, he says the experience of Brook House can change people.

“If you are like a nice person, very cool-minded, you will become aggressive - because you are facing aggressive things most of the time.

“The behaviour of the guys there, and the behaviour of the staff there, these are the two worst things.”

“You’ve got to have the urge to punch him in the face.”

“If he dies, he dies.”

From some of the officers, whose comments were picked up by Callum’s hidden microphone at different times, there is no sympathy - even the threat of violence - towards the people in their charge.

“With a lot of the officers, you do see them become desensitised. It just becomes the norm,” Callum says.

“People can’t cope and hand in their notice, but others become immune to the pain and suffering they see. Some turn to the other side and take part in the abuse.”

He says there is a group of officers in Brook House who are bullies, even boasting of hurting detainees.

Nathan Ward has been a priest for two years. He used to be a senior G4S manager.

He says he warned the company about the attitude of some officers three years ago.

Nathan Ward

“The vast majority were good, decent people,” he says. “But there was a group that actually concerned me on their relationships with detainees. It was around language that they used, a sense of roughness and the use of force - how force was used.”

Callum’s camera picks up an incident, which is the most distressing treatment of a detainee that he sees during his time undercover.

A man, who we will call Abbas, is in Brook House after being held on remand in prison.

He has been on suicide watch for two days because he was trying to harm himself.

Abbas was on suicide watch

The 20-year-old has already had to have a mobile phone battery removed from his mouth, and while Callum watches over him, he starts trying to choke himself with his own hands.

Callum calls for assistance and other officers rush in to stop the desperate man from harming himself.

But one officer didn’t just restrain him.

“This officer comes in and just chokes him basically. He just exerts all his pressure on from his hands and arms on to this guy’s neck, and you see his eyes roll back. You see his eyes roll to the back of his head,” says Callum.

Callum tells the officer he needs to ease off, and the man being restrained is eventually calmed down and released from the hold.

When force is used, officers are meant to fill out forms explaining what has happened. It allows managers to review incidents and consider what lessons need to be learned.

But in this case the restraining officer makes it clear to those who witnessed what happened that this should not be written up as use of force.

The officer involved later told Panorama that he couldn’t think of anything he had done that would get him into trouble. He has since been suspended.

In response to the Panorama allegations of mocking and abusive behaviour by a number of staff, G4S says it has suspended nine people and put five others on restricted duties.

A former G4S employee, who now works for the Home Office, has also been suspended.

G4S says it will take “appropriate action” once it has seen the evidence and continues that any such “behaviour is not representative of the many G4S colleagues who do a great job often in difficult and challenging circumstances”.

It also says it investigates all complaints and has confidential whistleblowing channels for staff and detainees.

This particular episode left Callum deeply shaken.

“I had to try and keep cool but immediately it was just messing me up,” he says.

“I went to the toilet and just started crying basically. And then I had to gather myself quite quickly because they’d be expecting me back on the wing.

“But actually, in the end when I think about that incident compared to the others, it’s the least disturbing in the sense that we managed to film it.

“So, what happened will be exposed, whereas there, for years, stuff like this has been happening and the people it’s been happening to aren’t being protected. It’s just being swept under the carpet.”

Later in the staff room, the same officer tells Callum to toughen up.

“We don’t cringe at breaking bones,” he says.

“If I killed a man, I wouldn’t be bothered. I’d carry on.”

It takes less than 10 minutes to drive the short distance from Brook House to the departures area of Gatwick Airport.

It makes it easy to get people who are being removed from the UK to their planes quickly.

Every few minutes there is the drone of aircraft taking off or landing to remind those held inside of the journeys that should lie ahead of them.

Detainees are locked in their cells from 9pm until 8am each day.

This was described as inappropriate by the prisons inspectorate in their most recent report (HMIP Brook House Inspection Report, March 2017).

This isn’t a prison, but like many of those institutions across the UK, the centre is struggling with the problem of drugs.

Everything that happens at Brook House is against the backdrop of what Callum describes as a Spice epidemic.

The centre is plagued by drugs, with many of the detainees using NPS or New Psychoactive Substances, specifically Spice.

Spice is often called “synthetic marijuana” or "fake weed" (Image: EPA)

“People start frothing at the mouth, they become violent, they become sick, they fit,” says Callum.

“I’ve seen people start trying to swim on a concrete floor because people go insane when they smoke NPS.

“And responding to an incident where someone has overdosed on NPS is is quite scary.

“It’s quite dangerous, and it’s worrying as well because people have died from overdosing on this stuff.”

Officers deal with a detainee who has taken spice

And there is a general fear that it will be just a matter of time before someone does die at Brook House.

“We were that close Thursday,” a member of staff tells Callum, referring to a day when several detainees collapsed.

“We had a first response and an ambulance. There were four of them. There is no shadow of a doubt someone will die.”

And Callum’s hidden camera also captures the desperation felt by some detainees.

“You are going to find one of us in a body bag,” one man shouts at officers. “Our blood is going to be on your watch.”

It takes less than 10 minutes to drive the short distance from Brook House to the departures area of Gatwick Airport.

It makes it easy to get people who are being removed from the UK to their planes quickly.

Every few minutes there is the drone of aircraft taking off or landing to remind those held inside of the journeys that should lie ahead of them.

Detainees are locked in their cells from 9pm until 8am each day.

This was described as inappropriate by the prisons inspectorate in their most recent report (HMIP Brook House Inspection Report, March 2017).

This isn’t a prison, but like many of those institutions across the UK, the centre is struggling with the problem of drugs.

Everything that happens at Brook House is against the backdrop of what Callum describes as a Spice epidemic.

The centre is plagued by drugs, with many of the detainees using NPS or New Psychoactive Substances, specifically Spice.

Spice is often called “synthetic marijuana” or "fake weed" (Image: EPA)

“People start frothing at the mouth, they become violent, they become sick, they fit,” says Callum.

“I’ve seen people start trying to swim on a concrete floor because people go insane when they smoke NPS.

“And responding to an incident where someone has overdosed on NPS is is quite scary.

“It’s quite dangerous, and it’s worrying as well because people have died from overdosing on this stuff.”

Officers deal with a detainee who has taken spice

And there is a general fear that it will be just a matter of time before someone does die at Brook House.

“We were that close Thursday,” a member of staff tells Callum, referring to a day when several detainees collapsed.

“We had a first response and an ambulance. There were four of them. There is no shadow of a doubt someone will die.”

And Callum’s hidden camera also captures the desperation felt by some detainees.

“You are going to find one of us in a body bag,” one man shouts at officers.

“Our blood is going to be on your watch.”

Harshad Purohit spent nine months in detention - three of them at Brook House - before being returned to India.

He was a student and care worker who stayed in the UK after his visa ran out.

For detainees like him, who didn’t take drugs, it made it an even more frightening place.

“In Brook House there is too much stress and taking of drugs,” he says.

“The effect of drugs - they can do anything, they can kill anybody… they are going too crazy.

“These drugs are banned, and I just don’t understand [how they] are selling [them] in this Brook House.”

The most recent inspector’s report described the supply and misuse of drugs at Brook House as the most significant threat to security.

Overall it found the centre was “reasonably good” and making excellent progress.

Into this environment, a new detainee arrives who really worries Callum.

Officers believe he has been used by one of his room-mates as a guinea pig to test out a new batch of Spice.

Callum is told the detainee's passport says he’s 18, but he doesn’t look it. He looks younger.

When Callum asks him how he is doing, his response is, “Not good.”

Harshad Purohit spent nine months in detention - three of them at Brook House - before being returned to India.

He was a student and care worker who stayed in the UK after his visa ran out.

For detainees like him, who didn’t take drugs, it made it an even more frightening place.

“In Brook House there is too much stress and taking of drugs,” he says.

“The effect of drugs - they can do anything, they can kill anybody… they are going too crazy.

“These drugs are banned, and I just don’t understand [how they] are selling [them] in this Brook House.”

The most recent inspector’s report described the supply and misuse of drugs at Brook House as the most significant threat to security.

Overall it found the centre was “reasonably good” and making excellent progress.

Into this environment, a new detainee arrives who really worries Callum.

Officers believe he has been used by one of his room-mates as a guinea pig to test out a new batch of Spice.

Callum is told the detainee's passport says he’s 18, but he doesn’t look it. He looks younger.

When Callum asks him how he is doing, his response is, “Not good.”

“How old do you think he looks?”

“He’s tiny. His face is really babyish.”

“He’s got to be about 12, hasn’t he?”

“They’re saying he’s 18. He’s not 18 at all. Lucky if he’s 15.”

Custody officers at Brook House are speculating about the detainee’s age, their conversations are picked up by Callum’s hidden microphone.

The detention centre is for adult men, not for children, but this boy has already been there for three days.

He says he’s 14.

According to the most recent Brook House inspection report, in the previous year there were 15 cases where there were disputes over the age of detainees.

Two of them were later found to be children - one had been at the centre for a month, the other for two.

Immigration rules are very clear, an unaccompanied child must not be held in an IRC under any circumstances.

Even if there is a dispute over their age, they should be treated as a child.

“The boy” detainee in Brook House

G4S rules are equally clear.

If a detainee claims to be a child, then the duty director and the Home Office should be alerted immediately.

Until this case is flagged, the boy is treated as an adult. He was living in a cell with a suspected drug dealer and a methadone user. He was moved into the care of the local authority, after two weeks.

“I’ve worried for him ever since I’ve seen him,” says Callum.

“The impact that this could potentially have on him and have on the rest of his life. Adults go into Brook House quite normal human beings, and they certainly don’t leave that way.”

Former G4S manager Nathan Ward wrote guidance on how to handle cases where it is suspected that a detainee could be under 18, while he worked for the company.

“What you have there is a child in an adult prison to all intents and purposes. We stopped doing that over 100 years ago,” he says.

“Everyone has failed in this circumstance. The immigration officer [who] put him in there in the first place. The reception, who admitted him into the centre, need to take action. The staff on the wings need to take action. The Home Office needs to take action. Everyone has failed this child.”

The Home Office says it does not comment in detail on individual cases. It told the BBC that its policy on age dispute has “not been breached in this case”, and that “the claimed age of the individual in question is in dispute”.

G4S says it can’t comment on specific cases, but any age issues are raised with the Home Office and children’s services.

“Last chance to stand up and walk - if not, you will be placed into handcuffs and you will be lifted. OK?”

Brook House exists to ensure those who are in the UK illegally, are removed from the country.

But Callum’s undercover filming shows a system that too often fails to do that.

The Romanian who wouldn't go

A custody manager is talking to a Romanian man who is refusing to leave his cell.

This is the first step in getting him to the airport so he can be returned to his country.

The detainee has served a prison term for attempted murder. He could have been deported immediately after his sentence ended, but instead he’s at Brook House.

The Romanian man in Brook House (r)

Callum is one of a team of officers in riot gear who have been sent in to make sure the Romanian begins his journey.

The man has a history of heart problems and immediately says he’s feeling unwell.

“Why you do this though, why you do this to me? Because I am sick… I am not feeling good. I am not good.”

A healthcare team is there to monitor him, but he insists he’s not going anywhere.

“No go. Not go my country,” the detainee says. “Big problem if I die here tonight, everybody is responsible.”

Eventually he is moved to another wing, from where he’ll be escorted to his plane.

The next day Callum sees him back at the removal centre. He is told that the man “pretended to have a heart attack” when he got to the plane and the pilot wouldn’t take him.

The Romanian man is going to great lengths to stay in the UK. In other cases bureaucracy gets in the way.

A detainee, who’d been at Brook House for two years after completing a prison sentence for murder, also got as far as the airport before being sent back.

The date of birth on the ticket provided by the Home Office didn’t match the date of birth on his passport.

The Algerian who couldn't go

Then there are the detainees who are desperate to leave - like Mustapha Zitouni - but can’t.

When his deportation home to Algeria was stopped at the last minute, he protested by jumping on to the suicide-prevention netting between the landings.

He refused to come down and had razor blades which could have been used to harm himself or others.

It took a specially brought in prison service team called the National Tactical Response Group to get him down from the netting.

Mustapha remembers how the day started.

“I was really happy, I prepared everything. My flight was 7 o’clock in the morning. They tell me, ‘Oh sorry, your flight has been cancelled because the Algerian Embassy didn’t provide [a] travel document. I expected to get free that day and see my people and my family.”

Mustapha arrived in the UK as an economic migrant on a false passport and worked illegally for 18 months. He has convictions for theft, assault and possessing drugs.

At the end of his last jail sentence he expected to be sent home immediately, but instead was detained at Brook House.

The day after Mustapha’s flight was cancelled, he summed up the situation to Callum.

“Maybe I done something idiot and stupid, but whole point [of an] immigration removal centre is removing people. And I want to go.”

Cancelled plane tickets cost the Home Office an estimated £1.4m a year, according to a 2016 report by the Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration.

The Home Office says it is “absolutely committed” to removing foreign national offenders from the UK - and each year it is increasing the number removed.

Callum later met Mustapha in North Africa

Mustapha spent nearly a year at Brook House, before finally being flown back to Algeria.

Now reflecting on what happened to him there he describes the detention as “a lot worse than prison”.

“In detention centre you never know how long you’re going to be [there] - one day, one year, or three or four years.

“The waiting game [is] the worst killer.”

The man who had nowhere to go

For some at Brook House the waiting game lasts years.

One detainee, who we’ll call Paul, has lived in the UK since he was six, but he was born in Somalia.

He describes himself as British, and his whole family is in the country.

Paul in Brook House

His leave to remain was revoked after he was convicted of burglary and drugs offences. He’s been detained since his prison sentence finished - nearly two years ago.

When Paul is told he’s going to be moved to another immigration removal centre he snaps, hooking a cloth that’s around his neck to the flush of a toilet and threatening to choke himself.

Paul threatened to choke himself in a toilet

Officers rush him and remove the ligature. He’s distraught.

“I want to come out of detention. I want my soul not to be in detention. But I can’t control that. That’s why I want to take my own life, because no-one wants to get me out of detention.”

That day he was moved to another immigration removal centre.

Professor Cornelius Katona is the clinical lead for the Royal College of Psychiatrists on the mental health of asylum seekers and refugees.

“From a clinical point of view, it’s not at all surprising that this man is enormously distressed by the length and indefiniteness of his detention,” he says - looking at the footage of the incident involving Paul.

“The chances of not being adversely affected mentally, by prolonged and indefinite detention, are very low.”

Brook House, which opened eight years ago, was originally designed to house people for up to 72 hours before they were deported, but the length of time people are being held is increasing.

The latest Home Office statistics show that in the year to June 2017 there were 200 people who left detention after being held for more than 12 months - with one person spending 1,514 days, more than four years, in detention.

The UK is the only country in the European Union that doesn’t put a specific time limit on immigration detention.

The Home Office says no-one is detained indefinitely.

“Our immigration detention policies and processes are in line with established case law, which stipulates that a person’s detention will be lawful only while there is a realistic prospect of removal within a reasonable period of time.”

It adds that what constitutes a “reasonable period of time” is “highly case-specific.”

Overall, the Home Office says “the dignity and safety of those in its care is of the utmost importance and that they regularly and closely monitor Brook House.”

And that “the detention of people without the right to remain in the UK who have refused to leave voluntarily is key to maintaining an effective immigration system.”

When Callum reflects on his experience of working in an immigration removal centre for two years he says “The amount of failed removals I’ve seen is just unbelievable.”

“The people that want to go aren’t being removed. And the people that we want to go as a society aren’t being removed.”

“It just makes a whole mockery of an immigration removal centre. The clue’s in the name.”