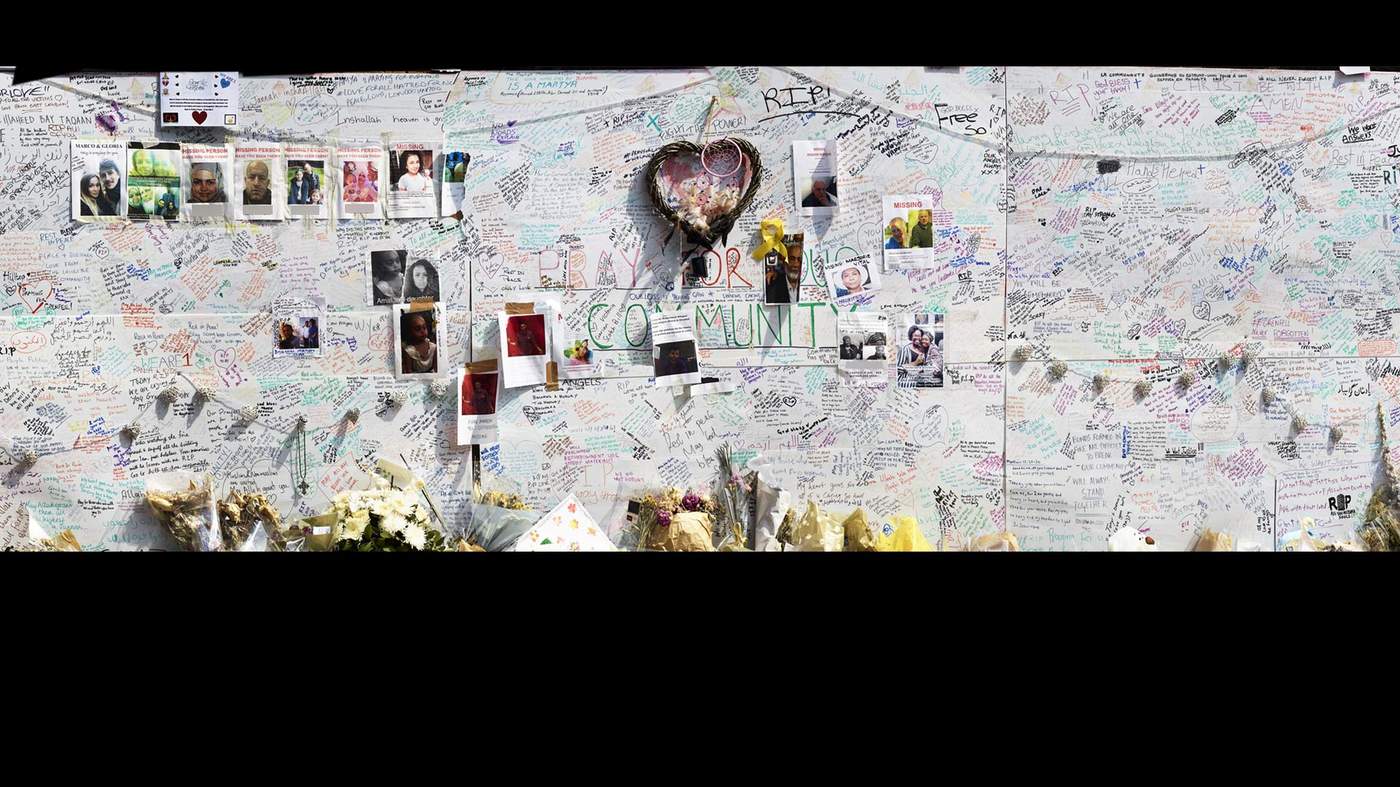

The Grenfell Wall sprang up overnight.

Within hours, hundreds of people had left messages of sympathy and support. Relatives of those missing brought favourite items, teddies and photos.

Missing posters were plastered everywhere, bearing the faces of those still unaccounted for and telephone numbers for anyone who might have information.

The wall is still there today in the shadow of the tower.

It provides a glimpse into the terrors that unfolded on 14 June 2017.

Jamie

The idea for the wall came from Jamie Sewell, who works for the Eden network, a charity that places youth workers on council estates to build links between communities and the church.

Jamie had lived alongside Grenfell Tower for five years and, in the immediate aftermath of the disaster, he drew from his experiences as a youth worker. He and his wife had opened their home to teenagers on the fringes of gang life. Three years before the fire, one of those boys had died. He was just 15 and Jamie had helped with the grieving process by providing a quiet space in the church where friends could meet and share memories.

With that in mind, the day after the fire, he took his van to a garden centre to buy large white boards, a little wicker heart and fairy lights.

His team of youth workers spent that day comforting people who were looking for loved ones, and talking to youngsters who were upset at what had happened.

Volunteers construct the wall

It was 20:00 BST when his exhausted team decided to finally close the doors of the Latymer Community Church.

Then, they set about creating the Grenfell Wall.

“All of our team, by that point, were just absolutely wrecked,” he says. “We started putting it up and we weren’t sure how it was going to be received. I think we were a bit nervous.

“We hadn’t even finished writing ‘Prayer Wall’, and we just quickly became swamped by people grabbing pens off us.”

Then, Jamie recalls, those around him “just started writing and pouring their hearts out on to these boards”.

A day later, Jamie’s boards were almost full and people started bringing their own down, attaching them along walkways surrounding the tower.

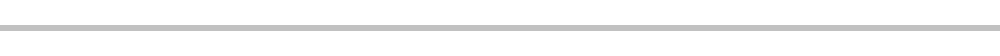

As well as writing messages, they laid flowers and wreaths, with firefighters hanging their shirts on the nearby railings, along with heartfelt messages describing their sorrow.

Firefighter's T-shirt

Families of some of those missing made small shrines and placed toys and photos next to candles as they huddled together waiting for news.

Children light candles

“People just started grieving together,” says Jamie. “For me it became a real place to go, among the madness and the chaos, to be quiet and just to walk around and read, and I suppose it made me personally feel a lot less lonely.”

Some of the first to write on the wall were volunteers who came from all over the country to bring food, water and clothing.

Listen to The Grenfell Wall, from BBC Radio 4, on the BBC iPlayer.

Naeem

Naeem Brisco runs a design company in Leicester and had woken to news of the fire.

He has overcome more than his own fair share of difficulties - from getting into trouble as a kid, then going against family expectations by marrying for love rather than letting his family find him a wife.

When that marriage broke down, he became homeless and was helped back on his feet by a stranger - which, he thinks, explains why he felt so moved to act in the aftermath of the Grenfell fire.

Naeem Brisco

He temporarily closed his business, brought his team together and loaded a van with supplies.

When he got to London, close to Grenfell Tower, Naeem unloaded his van by organising volunteers into a human chain that passed donations down to the supply centre.

Volunteers move the supplies:

Nothing had prepared him for the smell that hung in the area and the sense of distress as he helped a teenager look for his parents. The wall became Naeem’s way of making sense of the situation.

“Sometimes you’ve got to express yourself and by putting something in writing - I wouldn’t say it’s a closure, but it’s an element of you giving your condolence,” he says. “You felt good when you wrote something. You’ve given a message, you know what I mean?”

Naeem's message:

Naeem positioned himself close to the tower as he gave out supplies - food, water and clothing - to those searching for information.

School children with posters of Jessica Urbano

Some, like the schoolmates of 12-year-old Jessica Urbano Ramirez, wore T-shirts bearing her photo and face masks to protect themselves from smoke from the still-smouldering tower.

Maryam

Maryam Adam, for her part, was bewildered and full of guilt that she could have done more to warn her friends in the tower.

Maryam lived next to the flat where the fire started and her husband, Abdulwahab, had woken her after their neighbour alerted him to blaze.

She thought the flames would be easily extinguished and only agreed to leave because she was pregnant and worried about her baby. Her biggest regret is that she didn’t take her phone - as she watched the flames reach higher, she was unable to alert friends still trapped inside.

There had been great excitement among people she knew in Grenfell when she first told them of her pregnancy. In the days following the fire, she held out hope that friends might be found alive: Rania and her two daughters, Fethia and Hania; Nura and her children, Yahya, Firdaws and Yaqub; and Amal with her daughter, Amaya, who had an infectious laugh.

Poster: Amal and Amaya

Maryam moved into her flat in 2008, after 10 years of living in a hostel. She is from Somalia and grew up in Sudan, before coming to the UK in her 20s and loving everything about her new life. She and her husband shared their one-bedroom flat with her brother and his wife and they were happy - all the more so once she found out she was pregnant.

Her life was turned upside down by the fire and, a year on, she still struggles to make sense of it.

“I know many, many, many of my friends died. They died in Grenfell,” she says. “When you see somebody asking for help and you can’t do anything for them, it’s too difficult.”

The one piece of good news for Maryam was the birth, in November, of her son, Mohammed. Relatives in Sudan sent her traditional costume, which she proudly shows us as we talk.

The family are in temporary accommodation - it’s overcrowded, with boxes stacked in a corner and a makeshift bed for her brother in the small living room. There is no room for a cot for Mohammed, who shares a bed with his parents.

“You see, that is how we live. Just always we are dreaming, waiting just to get good news, but I don’t know if we are going to hear it or not.”

Maryam in temporary accommodation

She thinks of all the nights she spent not sleeping, worrying about her child.

“We are not living in our home, or anything like it. I don’t know where I’m going to move, where I’m going to live.

“And I’m fed up because I don’t know for how long I’m going to be waiting. We lost everything in Grenfell, we lost everything.”

Maryam gradually accepted that she would not see her friends again.

Amaya Tuccu-Ahmedin

She often thinks of little Amaya and the picture on the Grenfell Wall - a cheeky grin as the three-year-old plays outdoors.

Luke

It was taken by Luke Rosher, a teacher at St Peter’s Nursery on Portobello Road: “I took that photo actually, in the park, the playground - pure and innocent and lovely.”

The head teacher at the nursery, Tracey Lloyd, had got to know Amaya’s mother, Amal, well. Tracey laughs as she recalls the wonderful meals Amal would prepare on sharing days. Amaya’s dad Mohamednur was committed to his daughter’s education, having earned both a degree and an MSc since arriving in Britain. He was originally from Eritrea and had been active with anti-government forces there.

The family lived on the 19th floor of the tower and Amaya died in the arms of her mother. The pair held each other tight in their last moments of consciousness. The Grenfell Wall became an important part of the grieving process for nursery staff, who went together to remember the family. It also provided a way of helping young classmates who struggled to make sense of the loss.

Posters on the railings near Grenfell

One six-year-old neighbour of Amaya’s used red pencil to draw fierce flames over the windows of a tall tower. Other youngsters drew children screaming at windows.

Luke worked with his class to put together handprints on a remembrance board that they took to the site.

The poster the nursery children made for Amaya

A year on, he is repeating the task.

“I made a poster with the children, just little tiny handprints to show this is not just affecting grown-ups,” he says. “It is little children who are seeing this and living this and wanting to do this. There were, I think, 20 there and then we put a little message saying: ‘We miss you, Amaya.’”

Tracey says: “I feel very close to Amal and Amaya and Mo and the auntie when I’m there and I think it’s important that we do remember those families, those innocent lives that were cut short way, way, way before their time.”

Both Tracey and Luke remember the rush of emotions they both experienced when they first saw the Grenfell Wall.

“Just seeing all the tributes was just amazing,” says Luke. “It was so many conflicting emotions. There was obviously the sadness and, just disbelief - but then there was also this rush of, like, ‘Oh my gosh.’”

Tracey recalls “flowers everywhere, candles, and things that people had written - eulogies, their thoughts - friends, families, the fire brigade with their T-shirts, and it just seemed to go on and on and on”.

Firefighter's T-shirt

Many of those who survived the fire were given temporary hotel rooms in the surrounding area - coming back to the estate to collect clothes and register at the relief centre. They had lost everything, including passports, bank cards, phones and computers as they fled, but this paled into insignificance compared with the trauma of not knowing who had survived.

Miguel & Marcio

Miguel Alves and his wife Fatima were desperate for news of their friends Marcio Gomes, his wife Andreia and their two children, 12-year-old Luana and 10-year-old Megan.

They had heard nothing since around 03:00, when the family began their escape from the 21st floor. Fatima prayed that they would be found alive. Miguel made contact with the Portuguese authorities, who initially told him they hadn’t made it out.

The Gomes family had lived in the tower for 10 years

With so many gathered at the Grenfell Wall, rumours were rife. There was conjecture about the death toll and stories of a baby thrown from a window.

Missing posters came and went, with some marked “found”, and others staying intact. While Miguel and Fatima waited to hear about the Gomes family, their 20-year-old son Tiago looked at the missing posters put up by volunteers from Solidarity Sports, which provides activities and opportunities for disadvantaged children.

Miguel and Fatima, with their son Tiago and daughter Ines

Tiago, now 21, is studying physics at King’s College London and, passing the wall, he saw faces he remembered.

He recalled teaching 13-year-old Yahya Hashim how to knot his tie on his first day of secondary school.

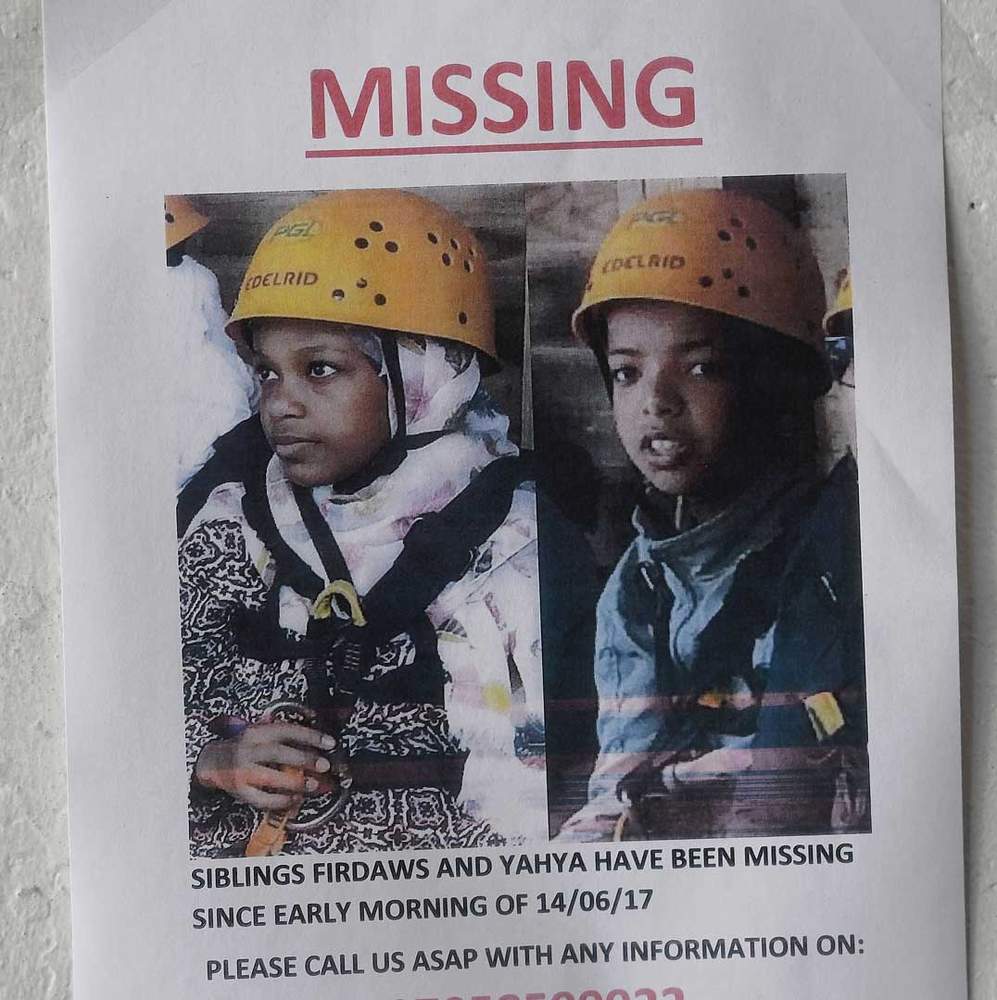

Missing poster: Firdaws and Yahya

There was also a poster of Steve Power, 63. Steve would give him advice while out walking his two bull terriers, telling Tiago to make the most of his education and that hard work would pay off in the end.

Candles and missing posters

Some nights, as he drifts in and out of sleep, Tiago realises:

“Oh wait, I’m not in my bed.” He hopes that in the morning, it will all turn out to have been a dream, and he’ll return to normal life. And then he wakes up and finds he is still in the hotel: “Oh, this did actually happen. As I’m trying to sleep, I almost pinch myself saying ‘Wake up now,’ because I can’t deal with it any more.”

Tiago and his sister, 16-year-old Ines Alves, had spent most of their childhood living in the tower and loved living there.

A year on, Ines is still receiving counselling, but says it is hard to cope with images from the night - people calling for help and phone lights in the windows - coupled with the loss of everything they owned and friends they cared for.

“Everyone knew each other,” she says. “You’d see each other in the flats and say ‘Hi’ or ‘Bye,’ or smile if you saw them in the street. It’s starting to hit me slowly, everything that’s happened. I still feel like I’m in a nightmare and tomorrow I’m going to wake up and go back home.”

The pictures of Yahya, 13, his 12-year-old sister, Firdaws and little brother, Yaqub, were taken by Sean Mendez, who runs Solidarity Sports.

The siblings had lived on the 22nd floor and, as soon as he heard about the fire, Sean went to hospitals searching for news. Since then he was worked with their aunt, Aseema Kedir, to set up the Hashim Family Legacy that, last October, enabled 16 children to fulfil the dream that Firdaws once had - to visit Walt Disney World in Florida.

Sean talks about helping children affected by the fire:

Similar legacies are being created by others, like Mike Volpe, the Director at Opera Holland Park. He lost a friend and employee, Deborah Lamprell, in the fire and he has organised a memorial concert to raise funds to help local children.

“We’ve called it Hope for Grenfell because yes, it’s a part-memorial, it remembers all those people, it remembers Debbie for us in particular,” he says. “But it also says we need to have some hope. Everyone’s got to go on despite the need for justice and to find out what happened but we do actually have to go on. There has to be some hope, somewhere.”

Miguel Alves kept hope alive while he waited for news of his missing friend, Marcio Gomes. But in the face of such a tragedy he knows it was only luck that spared him and his family.

Miguel and Fatima had been returning to their 13th-floor flat in the early hours when the lift stopped at the fourth floor. They saw the smoke and Miguel went up to wake his children and neighbours while Fatima waited outside.

The couple are originally from Portugal. He is a chauffeur and they had saved for the £82,000 they needed to buy their flat. Living there he had become good friends with Marcio and his family. As soon as he escaped, Miguel phoned Marcio and urged him to get out.

The fire service, however, had told the family to stay put. Twice they had tried to escape, but the smoke had beaten them back. With Miguel’s phone calls growing more urgent, Marcio contemplated the enormity of the decision he had to make.

“Miguel said, ‘Look, you need to go out’ and obviously he was getting very agitated about it, and I said: ‘I’ve already tried twice,’ he recalls. “Then I said: ‘It’s just pitch black,’ and it’s thick black smoke. You couldn’t even see your hand in front.”

Marcio could hear Miguel growing increasingly agitated and distressed. “You can see actually this is a lot worse than what you’re thinking. And also I had my neighbour and her daughter so, it’s a lot of responsibility if things go wrong. I’m thankful for Miguel because he made me more aware that this is really bad.”

As the flames grew closer, he realised he didn’t have a choice: “There was no way we were going to survive by staying.”

Marcio gathered wet towels and tried to stay at the rear of the building as they descended the stairwell.

“You couldn’t see anything,” he says. “It was pitch black, absolutely pitch black.” He didn’t notice the dead bodies at first.

“We only realised once we stepped on a body or tripped over - but there was nothing we could do for them and my focus was trying to get everybody downstairs. Luana and our neighbour’s daughter, they both then passed out at the same time. Didn’t see where they fell, you couldn’t see anything at all.”

It was firefighters who found the two girls and carried them to safety. They spent nearly a month in induced comas, as did 10-year-old Megan and Marcio’s wife, Andreia. She was seven months pregnant and, before the fire, the couple had decorated a nursery for the son they were planning to call Logan. On its wall they had written: “Twinkle, twinkle, little star, do you know how loved you are?”

Logan was stillborn when he was delivered and Marcio cradled him in his arms, willing him to breathe.

Marcio and Andreia tell how they escaped the blaze:

“I think we’re still processing it in all fairness, and I think we will always process it for the rest of our lives,” he says. “You’re never going to be 100% as you were before. You try to move on, you know - that’s how humans cope with things. There’s certain things I can’t talk about because I get really emotional - to do with the night, to do with my son.

“You try and make new memories and move on. I think you get better at controlling the emotions as time goes on but it’s still difficult and it will always be difficult.”

Marcio and Miguel have supported each other since the fire and feel that their weekly games of football provide an outlet for the grief.

Following the tragedy, other players donated kit and even football boots. Marcio is still experiencing some trouble with his breathing, caused by smoke inhalation, but seldom misses a game.

“You know it just helps, I think, for me,” he says. “Just to talk to each other and it just helps process what happened.”

Marcio and Miguel talk about their football games:

Fatima, meanwhile, takes comfort from the Cenacle of Missionary Prayer Group. The shrine she had in her 13th-floor flat was destroyed in the fire, but she has rebuilt it in her temporary accommodation. She says it is nice to finally have a kitchen to prepare family meals - she likes to cook and to entertain, something she did regularly in their Grenfell flat.

Fatima's shrine

When the family is on their own, the memories return, she says.

Miguel agrees. They have to enjoy life, he says. “We can be ashes inside of the tower, you know? Life is too short.”

The couple have had counselling since the fire, as have their children. Ines is now in sixth form, having passed the GCSE chemistry exam she sat the day after the fire. The family recently were allowed to see inside the shell of their old flat but were not really prepared for how upsetting it would be.

Fatima recalls seeing the metal frame from her son’s bed and his desk bent out of shape. “It was very sad,” she says. “I started crying when I saw that because in my mind, from the beginning, I said: ‘No, something will be saved.’

“It was hard to see.”

Since then, they have been sent three small boxes and two larger ones containing items salvaged from the ashes - the mugs that were inside the metal dishwasher, some coins from Tiago’s piggybank, a watch and a small cross, which is singed black around the edges.

Miguel and Fatima's possessions

Everything is in small see-through pouches, each of which smells of the fire when they are opened. It is emotionally draining and, to date, Fatima has emptied just two of the five boxes, and she has no idea whether or not to keep things.

They are a reminder of her past life, but it is painful to see the state of them now. The family will soon move into a more permanent home, a nice house close to their old flat - a place they can finally call home.

Thomas

One of the first people to place a missing poster on the memorial wall was Thomas Murphy, originally from Ireland, who is a member of several community groups in the area and has lunch twice a week at the Salvation Army in Portobello Road.

Maj Paul Scott, who oversees things there, says it was all hands on deck when the fire broke out, with Thomas and other volunteers helping sort out the donations and get people the help they needed.

“Everybody just pulled together. It didn’t matter what religion we were or they were. We were amazed because we had about 80 people at one point who were looking for missing friends and relations.”

This was particularly true for Thomas and the lunch club participants who knew some of those affected. For 90-year-old Olive it was painful to witness her granddaughters upset at losing a classmate, five-year-old Isaac Paulos. Marjory, 61, mourned the death of Marjorie Vital, who died with her 50-year-old son, Ernie.

As locals they pass the wall, sometimes seeing vigils and memorial services, like the one held for 29-year-old Berkti Haftom and her son, Biruk, who was 12.

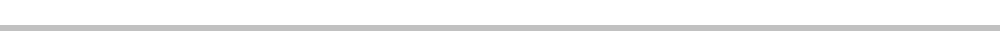

The fire shattered many close bonds - for Thomas it meant the loss of his friend, Vincent Chiejina, who was born in Nigeria and, like him, was active in the Open Age Charity and St Francis of Assisi Church in Notting Hill.

Thomas put up missing posters even though he knew his search was probably in vain: “I wasn’t naive to think that he had escaped out of that because I stood there that night and I watched that inferno.”

Missing poster: Vincent Chiejina

In the aftermath, Thomas printed out photos and went to the Grenfell Wall, asking anyone he could find for news of his 60-year-old friend, who lived alone on the 17th floor. During the weeks that followed he found out more about Vincent, who he says had always been protective of his privacy, but was incredibly caring and determined to help the most vulnerable in society.

Vincent and Thomas

“I just appreciated him and I found him to be a nice person,” Thomas says. “And eventually he told me what happened to him, that he was studying at university - mathematics was his forte - and then snap, his mind went.

He told me as much as he wanted to and that was it, I left it at that, being discreet about it, you know. Whatever it was, it did a lot of harm to him. And I thought: ‘My God, ending up on that floor on your own.’ And he’s not alone, he’s not alone in that position.”

The community

For the community, the fate of the Grenfell Wall is still to be decided. At the moment, sheets of plastic help preserve the messages of love and support.

Some local residents are angry that the wall has not been removed and feel that it is stopping people from moving forward. One woman who asked not to be named points to sightseers drifting by and camera crews in the area.

“Tacky. It’s beginning to look tacky,” she says. “So how long does that stay there? Where does it all go, that stuff? And when? We all need to move on. There have been vigils after vigils and you come home and it’s like - how many memorial services do we need? And who are these actually for?”

For his part, Jamie Sewell, who first put up the boards, sees this as an important opportunity to consider important issues raised by the fire.

Jamie Sewell

He hopes that some form of permanent legacy is forthcoming. The next challenge for the community, he says, is figuring out how it will remember the tragedy.

Some people on the outside think that Grenfell is something that happened in the past and it's not happening any more, says Jamie: “But actually, there is still so much grief, so many questions.”

One year on, looking at the wall “makes me realise that we were all in it together and we were all feeling much the same kind of thing - there’s anger, a massive sense of loss, a massive sense of injustice and a massive sense of confusion”, he says. “I think that’s what the Grenfell Wall ended up representing.”

Look at the Grenfell Wall:

See the messages in close-up.