Fabian is world renowned for destroying ransomware - the viruses sent out by criminal gangs to extort money.

Because of this, he lives a reclusive existence, always having to be one step ahead of the cyber criminals.

He has moved to an unknown location since this interview was carried out.

Words by cyber-security reporter Joe Tidy

Illustrations by Aart-Jan Venema

For the photographer from Yorkshire, UK, it was nothing short of a disaster.

Late one night he was putting the finishing touches to his latest set of wedding photographs due for delivery to his excited newly-wed clients. Then everything on his computer screen changed. Not just the folder of pictures, but his entire body of work, emails and invoices were gone.

For the school head teacher in Texas, US, it didn’t hit home how serious it was until she remembered what her computer contained.

The detailed, long-term financial plan for her already stretched high school. It had taken months of work and huge investment to plan for the future and, with the click of mouse, the hackers now had control.

For the senior manager of a large corporation in Hong Kong, it was instant cold sweat.

He had heard about this type of computer virus and how dangerous it could be. But he never thought that he would be tricked into clicking on a wrong link. Now, as he read the ransom note, he panicked. This could cost him his job.

Ransomware is a particularly nasty type of computer virus.

Instead of stealing data or money from victims, the virus takes control of computers and scrambles every single document, picture, video and email.

Then the ransom demand is issued. Sometimes it’s written inside a note left on a desktop, sometimes it just pops up on a screen without warning.

Fabian is world renowned for destroying ransomware - the viruses sent out by criminal gangs to extort money.

Because of this, he lives a reclusive existence, always having to be one step ahead of the cyber criminals.

He has moved to an unknown location since this interview was carried out.

Words by cyber-security reporter Joe Tidy

Illustrations by Aart-Jan Venema

For the photographer from Yorkshire, UK, it was nothing short of a disaster.

Late one night he was putting the finishing touches to his latest set of wedding photographs due for delivery to his excited newly-wed clients. Then everything on his computer screen changed. Not just the folder of pictures, but his entire body of work, emails and invoices were gone.

For the school headteacher in Texas, US, it didn’t hit home how serious it was until she remembered what her computer contained.

The detailed, long-term financial plan for her already stretched high school. It had taken months of work and huge investment to plan for the future and, with the click of mouse, the hackers now had control.

For the senior manager of a large corporation in Hong Kong, it was instant cold sweat.

He had heard about this type of computer virus and how dangerous it could be. But he never thought that he would be tricked into clicking on a wrong link. Now, as he read the ransom note, he panicked. This could cost him his job.

Ransomware is a particularly nasty type of computer virus.

Instead of stealing data or money from victims, the virus takes control of computers and scrambles every single document, picture, video and email.

Then the ransom demand is issued. Sometimes it’s written inside a note left on a desktop, sometimes it just pops up on a screen without warning.

They always come with a price tag. Pay the hackers a few hundred pounds - or sometimes thousands - and they’ll restore your files.

All of the victims mentioned above were hit with some form of ransomware. But the Hong Kong businessman didn’t lose his job and the photographer and head teacher were able to recover their work.

None had to pay any money, and once they’d got their lives back in order, all sent emails of thanks to the same person.

He’s a man who has devoted himself, at huge personal cost, to helping victims of ransomware around the world. A man who guards his privacy dearly to protect himself, because for every message of gratitude he receives, almost as many messages of abuse come at him from the cyber criminals who hate him.

In fact, they hate him so much that they leave him angry threats buried deep inside the code of their own viruses.

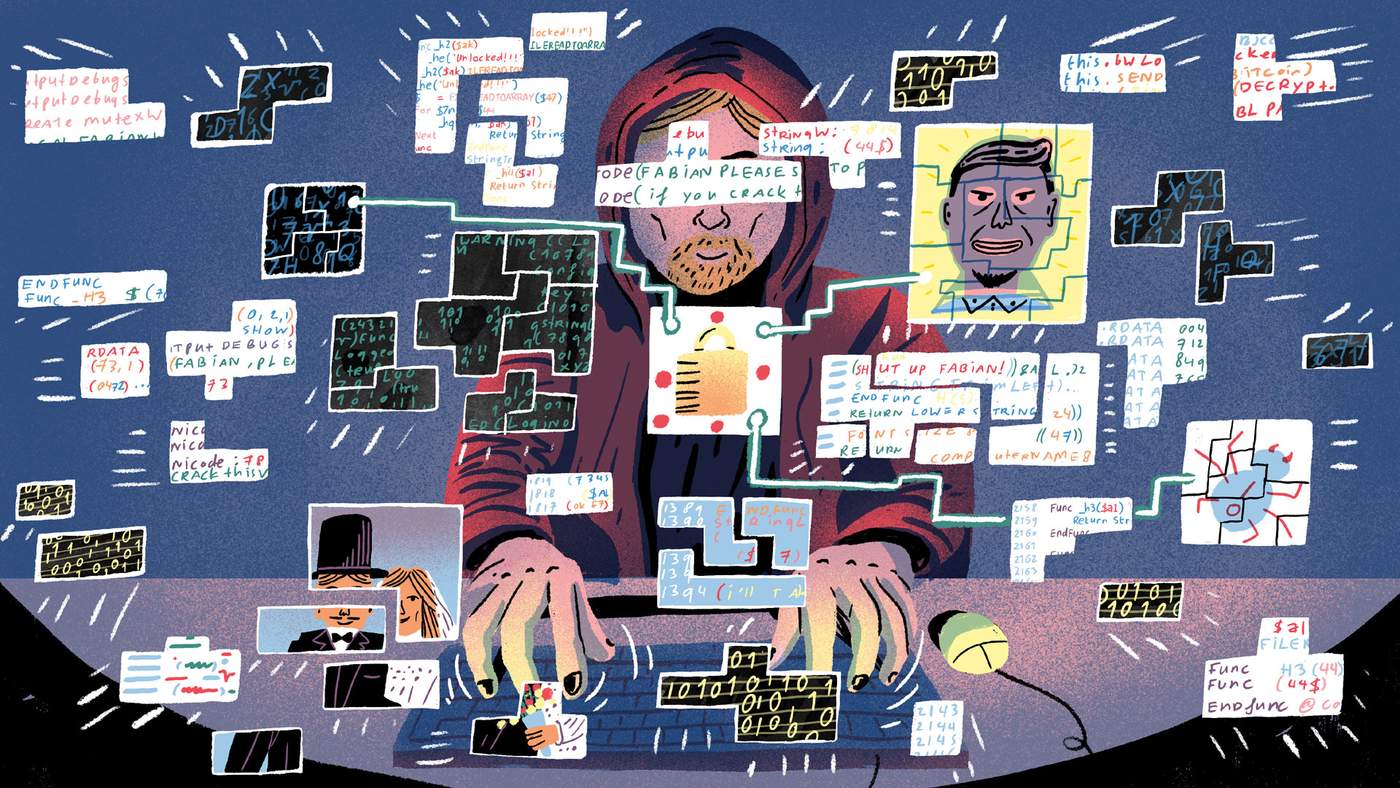

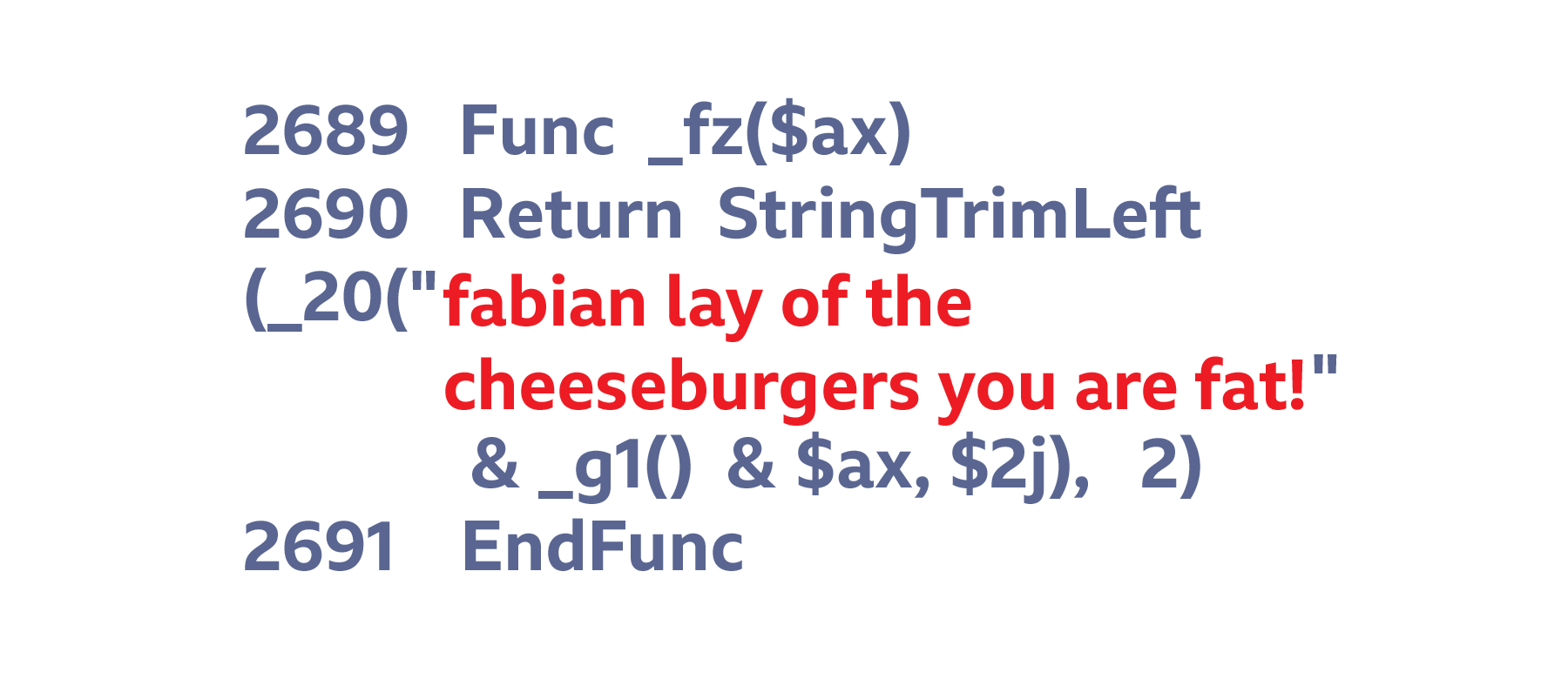

To the untrained eye, the code of a computer virus is just a jumbled mess of letters, numbers and symbols.

But to Fabian Wosar, each line is a clear instruction. He knows and understands every digit and dot in the same way a pianist would read a page of musical notes.

About a year ago, as his eyes darted around the screen looking for a clue to help him crack the latest ransomware, he was stopped in his tracks. Standing out amongst the code, in glaring green letters, were expletives referring to Fabian. By name.

“I was shocked but I also felt a real sense of pride,” says Fabian. “Almost like, a little bit cocky. I’m not going to lie, yeah, it was nice. It’s clear that the coder is really pissed.

“They’ve taken the time and effort to write a message knowing that I’ll probably see it and I’m clearly getting under their skin. It’s a pretty good motivator to know that my work is upsetting some really nasty cyber-criminal gangs.”

Fabian shows me other messages. It takes me a while to spot them as I scroll through endless strings of code. When I find one it stands out like a beacon in the sea of otherwise unreadable characters.

Nearly all are obscene, offensive and threatening. There are frequent references to Fabian’s mother, and descriptions of sexual acts are common. Many are goading and taunting Fabian.

One virus was even named “Fabiansomware” in an attempt to fool the victim into blaming Fabian.

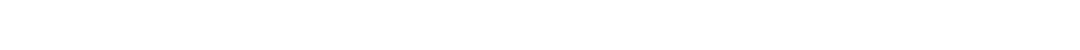

There are some, though, that are more pleading in their tone, such as this one he found a few months ago.

“They tried to make me feel guilty with this one. But obviously I still cracked their virus and released a decrypter,” he says.

“Surprise, surprise it didn’t stop them and they released another version.”

Fabian keeps every message he finds. They form a large collection on his computer and are just another motivator that keeps him dedicated, even obsessed, with his work.

From the minute you step inside Fabian’s home you can see how that dedication manifests itself in his life.

His unassuming terraced house on the outskirts of London has no decorative furnishings at all. No pictures or paintings adorn the walls. No lamps or plants. The shelves are empty except for a collection of Nintendo games and some computer coding manuals.

He owns one board-game called Hacker: The Cyber Security Logic Game, which he admits he’s very good at - although he’s only ever played it alone. In short, his home isn’t very homely but this cheery, energetic young German doesn’t seem to mind. He even admits to spending “98%” of his time at home as he works from his office upstairs.

“I’m one of those people who if I don’t really have a reason to go outside, I won’t,” he says.

“I don’t really like to leave the house unless I have to. I do nearly all my shopping online and get everything delivered. I don’t really like too many things around as I spend nearly all of my time working.”

Strangely, Fabian has chosen the smallest room in his house to set up his office. This is where, with the curtains closed, he toils away for most of his waking life gaining grateful fans and hateful, dangerous enemies around the world.

He works remotely for a cyber security company, often sitting for hours at a time working with colleagues in different countries.

When he’s “in the zone”, the outside world becomes even less important and his entire existence focuses on the code on his screen. He once woke up with keyboard imprints all over his face after falling asleep during a 35-hour session.

All of this to create anti-ransomware programs that he and his company usually give away free. Victims simply download the tools he makes for each virus, follow the instructions and get their files back. You can see how he has built up such a vengeful group of angry cyber criminals.

“We are never completely sure who we are dealing with, but my guess is that I have upset or angered around 100 different cyber gangs over the past few years,” says Fabian.

“Writing code is like writing a novel. You can tell from the style. You can tell that you’re dealing with the same gangs quite often. It’s also pretty easy to follow the money. By looking at the Bitcoin wallets that the gangs ask victims to pay into, you can see who is responsible for each variation of ransomware and how much money they’re making.”

He says that one group he “annoyed a lot” had made about $250,000 (£191,000) in three months - until he found their virus and stopped it.

Ransomware is one of the most profitable ways for cyber criminals to make money.

Stealing data is fine but you still need to find a buyer. In these attacks the victim is the buyer. Individuals rarely have backups of precious family photos, so are likely to pay the few hundred pounds to save those memories.

Businesses often pay without alerting the authorities or upsetting shareholders. In some cases, local authorities pay after weighing up the cost of replacing their systems at taxpayers’ expense.

In March, officials in Jackson County, Georgia, US, reportedly paid $400,000 (£301,000) to cyber criminals to get rid of a ransomware infection and regain access to their IT systems. It was reported that they had estimated it would cost millions to replace the computer network.

The most successful cyber-crime gangs are run like mafia organisations with specific structures and divisions of labour.

There are the virus coders, the money launderers, the protection heavies and the bosses who decide on targets and sometimes funnel the money into other, potentially more serious, criminal enterprises.

Catching these gangs is extremely challenging. One of the most prolific recent ransomware gangs, responsible for two major ransomware families - CTB-Locker and Cerber - made an estimated $27m and eluded police for years.

It took a global police operation involving the FBI, the UK’s National Crime Agency, and Romanian and Dutch investigators to bring them down. In December 2017, five arrests were made in Romania.

According to research from Emsisoft, the cyber security company Fabian works for, a computer is attacked every two seconds.

Their network has managed to prevent 2584105 infections in the past 60 days - and that’s just one anti-virus firm of dozens around the world.

Some of the most destructive cyber-attacks in recent years have been carried out with ransomware.

In May 2017, hundreds of British hospitals were plunged into chaos as a ransomware virus called WannaCry spread like wildfire through the NHS computer network.

An estimated 70,000 devices – including computers, MRI scanners, blood-storage refrigerators and theatre equipment - were taken offline by the virus, which encrypted machines and demanded a payment in Bitcoin to save the files.

Doctors and nurses were forced to resort to pen and paper and thousands of appointments and operations were cancelled or postponed.

Worldwide, the ransomware claimed an estimated 300,000 computers in 150 countries, with systems in Russia, Ukraine, Taiwan and India worst affected.

It didn’t take long for experts to blame hackers in North Korea for the attack, which is estimated to have caused hundreds of millions of pounds of damage.

Another piece of ransomware called Not Petya is responsible for what is often described as the most devastating cyber attack of all time. This one is estimated to have caused $10bn (£7.6bn) in damages with around $300m of that coming from one company.

It was in June 2017 when the infection began.

It originated in an otherwise benign piece of accountancy software popular with Ukrainian companies and spread throughout the country encrypting computers at energy companies, transport networks, airports and banks. Quickly, the virus scrambled files on computers in Germany, France, Italy, Poland and the UK.

NotPetya was particularly cruel in that although it looked and acted like ransomware, it was effectively a “wiper” - even if victims did pay the ransom (and many did), the files could never actually be recovered.

The company worst hit was Maersk, the largest logistics and container ship firm in the world. The entire business nearly ground to a halt and in the 10-day scramble to rebuild thousands of networked computers the price of commodities like bananas began to soar as shop shelves went bare.

It’s believed this attack was politically motivated against Ukraine but no-one really knows who was to blame.

“It’s pretty much an arms race,” says Fabian. "They release a new ransomware virus, I find a flaw in its code and build the decryption tool to reverse it so people can get their files back.”

“Then the criminals release a new version which they hope I can’t break. Sometimes they figure out what they did wrong and fix it, but a lot of the time they can’t see the flaw in their code.

“In one case this back and forth with one cyber-crime gang went on for like six or seven months. It escalates with them getting more and more angry with me.”

When he’s immersed in the race against these anonymous criminals, Fabian admits it is hard to keep on top of even the most basic functions like eating and drinking, and looking after himself.

Amongst the mess of coding books and paperwork on his desk I spot two pill boxes. The containers with labels for each day of the week point to health issues, which he admits are a direct result of his lifestyle.

“I’m heavily overweight and I have trouble with my blood pressure so I take some meds for that. I also struggle with hyperthyroidism,” he says.

“It’s definitely down to my work and how I live. I’m actually thinking of getting a puppy to force me to leave the house for walks. And the companionship would be nice too.”

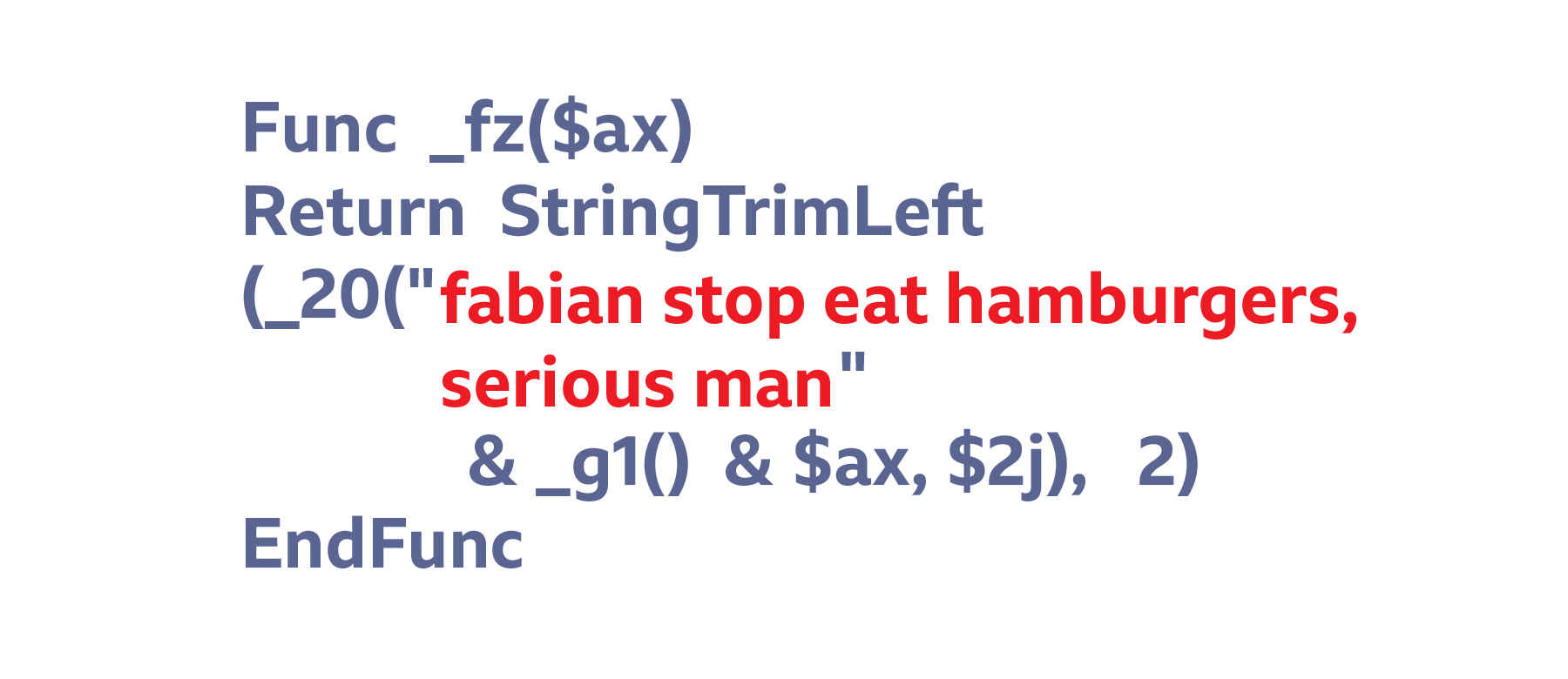

It was another message specifically about his weight that led him to flee Germany and end up in the UK.

About a year ago, he came across a hidden message which, unlike most, was terrifyingly personal:

This one he couldn’t ignore. Not because it hurt his feelings but because it showed that the cyber criminals knew something about him.

Up to this point he had kept everything except his name a closely-guarded secret.

Not even his boss or co-workers knew where he lived in his hometown in east Germany, and now it seemed the net could be closing in with the criminals.

“It definitely got to me. Not because of the overweight thing - because I clearly am overweight - but because I realised people were kind of stalking me online,” he says.

Fabian describes it as a creepy time. He scoured his social media accounts and web forums for any pictures or references to his appearance. He found that years ago, a throwaway tweet had mentioned the Keto diet.

“That was when I removed my birthdate everywhere and things like that to not give too many clues,” he says. “I remember thinking I had to get out of Germany, where you can easily have your location found with a few pieces of information.

“It was very scary. I don’t think they would have killed me but these guys are highly dangerous. I know how much money they make and it would be literally nothing for them to drop 10 or 20,000 for like some Russian dude to turn up to my house and beat the living hell out of me.

“I moved to the UK as soon as I could. You can hide here, there are no registers or anything and I can be anonymous.”

Fabian still hasn’t told his co-workers exactly where he is in the UK.

He only agreed to have a visit from me because he is just about to leave the area and won’t tell me where he’s going.

Fabian accepts that moving around and restricting his life and circle of friends is just a part of the sacrifice for his hobby-turned-profession.

He first discovered his passion for computers at the age of seven when he played on his dad’s work computer. Coming from a poor family in the former East Germany it was up to him to pursue his dream. He spent three years saving up the money for his first computer by collecting recyclable bottles and cans and selling them back to the council.

At the age of 10 he had enough money to buy the machine and he began experimenting. This really took off when he got his first computer virus.

“The virus was called TEQUILA-B. It messed my system up in all kinds of ways and I got really, really fascinated by it. I went to a library and they actually had a couple of books about computer viruses. I got into it and wrote my own antivirus program.”

By 14, he was known throughout the municipality as the go-to-guy for computer problems and managed to save enough to help his family get a better house in a better neighbourhood.

By 18, with no formal education or training, he joined cyber security firm Emsisoft where he has built his profile and is known in the industry as one of - if not the - best ransomware expert.

With his skillset and notoriety, Fabian could be one of the biggest names and personalities in the cyber world but he chooses a more modest life.

He earns a very good salary but looking around his home and at his life it’s hard to see how he spends it.

“I don’t really spend my money, no. I like to play tabletop games online but that doesn’t cost much,” he says. “A lot of my money I send to my sister who has a little girl. I like to make sure she has everything she needs.”

He gets offered thank yous and rewards all the time but doesn’t like to accept.

One gift he was happy to accept, though, was a cartoon picture of what a grateful illustrator imagined he might look like. It shows a portly man wearing a polar bear hat. Bizarrely, she has managed to capture his essence (and love of polar bears) without looking much like him.

He uses it as his online avatar, happy knowing that it came from another person he’s helped, but safe in the knowledge that his secret identity is secure.

As I leave him, I feel privileged to have been invited to his home - one of very few people to be trusted with his location, albeit temporarily. I wish him good luck with his house move and the hunt for a puppy companion to share his strange life with.