The bet

I have a memory of my dad from the 1980s.

Every summer we would drive to France, taking the ferry from Portsmouth to Le Havre. As we were about to dock, people would get into their cars and start their engines.

There would be a 10-or-15-minute delay before the doors opened and the cars started down the gangplank on to French soil. Until that happened, exhaust fumes began to fill the car deck.

My dad would rail against the practice. He would tap on people's windows and ask them to turn off their engines. In those days there was lead in petrol, but the main problem was carbon monoxide.

Dad was a surgeon and here were people needlessly filling their bodies with toxins from their exhausts. All because they couldn't wait to turn that key in the ignition.

Tom and his parents on a ferry to France in the 1980s

At the time I was embarrassed. Why were we always the last ones to turn our engine on?

It's more than 30 years since those Townsend Thoresen ferry crossings. And today what gets me is this - these days my dad drives a diesel.

Tom and his dad, Hubert

Diesels are in the newspapers nearly every day. They are killing thousands of people in the UK every year, we read.

The diesel driver is a new kind of bogeyman.

But when I ask my dad when he's going to scrap his car for the good of humanity, he looks at me with a mixture of surprise and annoyance. “Why would I do that?”

Three weeks later I am near Wandsworth Bridge, stuck in a line of traffic that jerks forward a foot or two at a time.

It is early July, London is in the grip of a heatwave and Melvyn, my 23-year-old VW Golf, has no air-con.

I have my window open and you can almost chew the 30C air - a soupy sludge made from the exhaust gases of the cars, buses and vans around us.

Beth, my partner, asks me to close the window for the sake of our 11-week-old baby asleep in the back.

We start to argue about which is worse for our daughter - overheating or exhaust fumes.

Beth wins.

The windows are shut, the car gets warmer, but at least we are keeping the noxious gases out. Or some of them.

These two experiences will lead, months later, to a family experiment. Father and son, two cars, and the same type of emissions test that rumbled VW.

We want to find out whose car is worst for human health.

The result is interesting. But the real surprise is that few people really know what their cars are doing to us, and that some new cars are far, far worse than others, and even worse than some old cars.

I'd been thinking about London's air ever since Beth and I moved back from a year in the French countryside.

In January 2017, a month after our return, London briefly overtook Beijing for levels of particulates - tiny soot particles that can lodge in the lungs or enter the bloodstream.

Londoners were advised to reduce their physical activity, particularly outdoors.

Across the UK, vehicle pollution in the form of particulates and nitrogen oxides was killing 40,000 people per year, according to government figures.

Aberdeen, Birmingham, Bournemouth, Burnley, Chelmsford, Derby, Leeds, Northampton, and Sheffield were just some of the towns and cities mentioned for exceeding limits on nitrogen dioxide.

Hang on, I thought, weren't engines supposed to be getting cleaner?

The Volkswagen scandal two years ago showed just how untrustworthy official emissions figures were for diesels.

While particulates are the achilles heel of older diesels, new diesels have efficient particulate filters.

What they struggle to control is NOx - oxides of nitrogen, the most harmful of which is nitrogen dioxide.

In the US, researchers believe there is a strong link between inhaling nitrogen oxides and lung and heart problems, and this has resulted in tighter emission limits.

In order to get its diesels into the country, VW realised it would have to cheat.

So it installed “defeat devices” in the car's on-board computer that would recognise when a test was taking place and lower NOx emissions for the duration of the test.

For older cars - petrol or diesel - emissions figures simply aren’t available.

Even if you trust the official figures issued when they were first made, the engines will have become less efficient and more polluting over time.

But how much? You’ll be hard pressed to find out.

Mulling all this over, an idea began to take shape.

My dad and I had two very interesting cars. The kind of cars that would be held up as just the kind we should be scrapping.

Why not test my ageing petrol Golf against dad's newer Skoda Octavia diesel?

It would be Top Trumps - but for emissions rather than 0-60 in 3.8 seconds.

I was hoping our two cars would tell us something about the existing stock of cars on the road.

My dad's car was made in 2009, so it's eight years old, the average age of a car in the UK.

Mine, at 23 years old, is a senior citizen. But that too would tell us something about petrol engines from the distant past and how they age.

Despite the outcry about air quality, no-one really knows how to frame the problem.

Is it all to do with the type of engine - diesel v petrol? Is it the age of the engine - are old bangers the problem? Or is it about the manufacturer - are some makes better than others?

And then what about NOx and particulates - are some good on one and poor on the other?

And where does that leave carbon dioxide emissions, the greenhouse gas now rather forgotten in our focus on the more immediate peril of particulates and NOx?

In late July the government published its air quality plan - after being compelled to by the High Court. The document put the onus on local authorities to enforce controls where limits on NOx were being exceeded.

Highly polluting vehicles could be charged or banned from certain areas. A car scrappage scheme was not in the plan but neither was it ruled out.

London has already jumped the gun with its T Charge, to begin on 23 October, which will charge drivers of pre-2005 cars (Euro 1, 2 or 3 in the jargon) an extra £10 to enter the congestion zone, regardless of whether their car is petrol or diesel.

It is a precursor to the much more ambitious Ultra Low Emission Zone, penalising any vehicle made before autumn 2009 (pre-Euro 5) - which now seems likely to come into force in 2019 and to cover a large area between the North and South Circular ring roads.

In other words, local government is coming for you. But are they going after the right targets?

At a certain point my mother and father go to a lecture by Prof Frank Kelly who advises the government on the medical effects of air pollutants.

He paints a stark picture.

The closer you get to an exhaust pipe the more serious the problem is, the air at a busy junction is worse than on a quiet street a stone's throw away.

Kelly recommends using back streets and keeping away from the kerb. This is not some amorphous cloud. Each individual car's exhaust is causing damage to individual people on every street. Dad was fascinated but also concerned.

I sense his attitude has mellowed since we last discussed diesels. I seize the moment.

We always used to buy petrol cars when I was growing up. So why, about 15 years ago, did he switch to diesel?

It was to do with fuel economy, he explains.

You can go further on a gallon of diesel, and in France - on holiday, travelling long distances - it was much cheaper.

Hubert de Castella - Tom's dad

Diesel was not seen as perfect, he recalls.

He remembers being encouraged to phone a hotline to report dirty diesels with their telltale black smoke.

But a well-tuned diesel was seen as the superior technology for miles per gallon and carbon dioxide emissions.

Indeed, when I check I see that in 2001 the then chancellor Gordon Brown introduced tax breaks for diesel cars because of their lower CO2 emissions.

“We didn't think much about NOx at that time,” my dad says.

“It's all come to light, the actual forms of pollution, in the last two or three years as far as the public are concerned. It shows that people do the wrong things for the right motives.”

But knowing what we do now, shouldn't drivers like him be penalised? (I'm enjoying grilling my dad the way he has often grilled me over the years.) He isn't fazed though.

“I think once the word ‘penalising’ comes into it people would start litigation saying, 'You got us into this mess, so how dare you penalise us for what we've done on your behalf,’” he replies.

It seems to me that one might also blame those carmakers who have helped disguise the extent of the problem, either by cheating or simply by designing cars that pass emissions tests in the lab but continue to emit high levels of pollutants in real-world driving.

And this brings me on to my final question. I ask if he's willing to submit the Skoda to an independent emissions test.

“My Golf versus your Skoda, may the best car win - what do you say?”

He thinks about it for a second, smiles and nods wearily. I sense that deep down he's also curious to find out what his car is pumping into the air.

It's a bet of sorts. So what about the stakes?

We settle on a pint.

I may have my Dad on board. But how do you even get a car tested for emissions?

You can't just walk in off the street and ask a garage for a NOx or particulate test.

A garage tests emissions as part of the MoT. But it’s quite a crude system - it doesn't pick up NOx and misses invisible particulates.

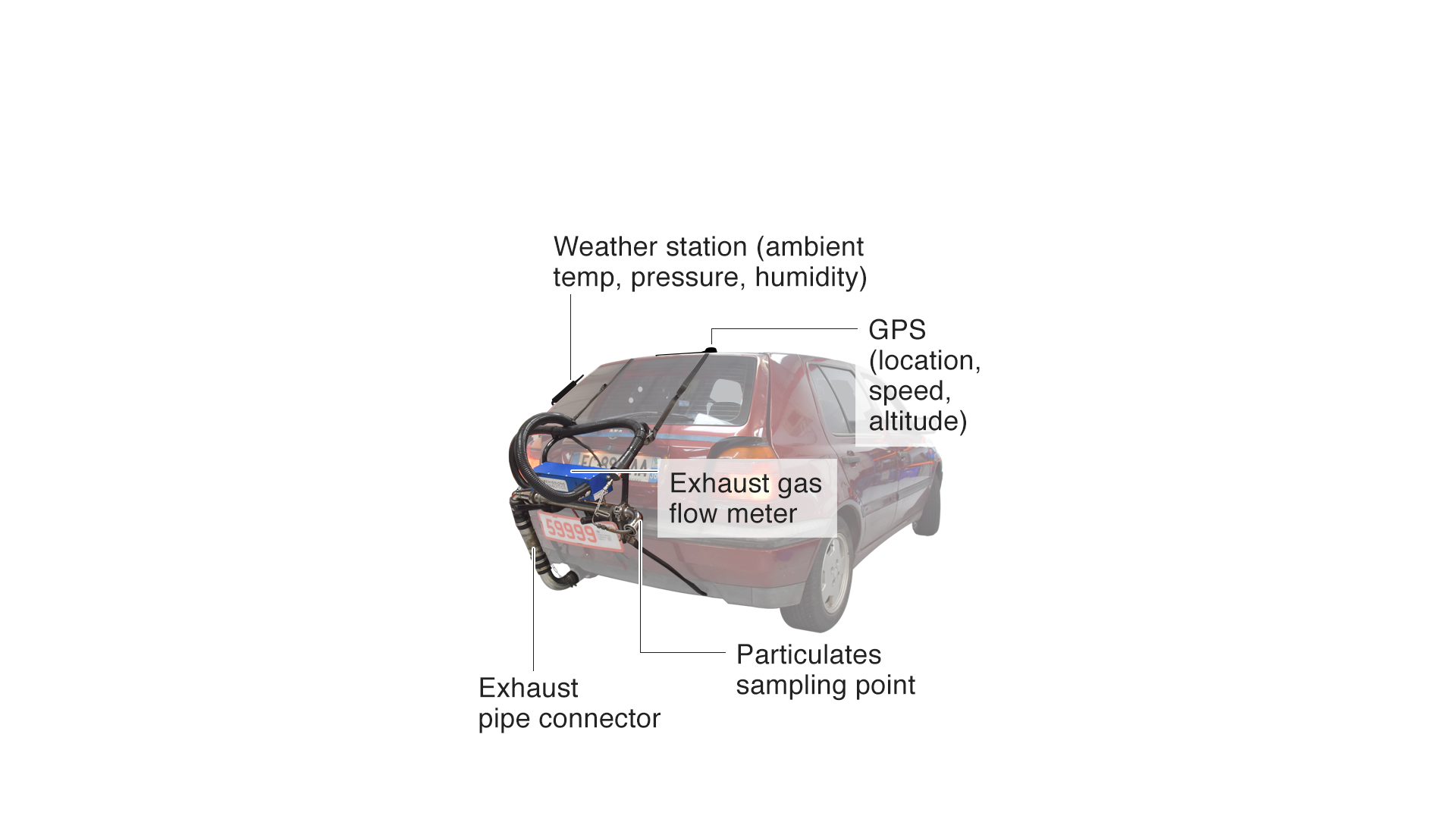

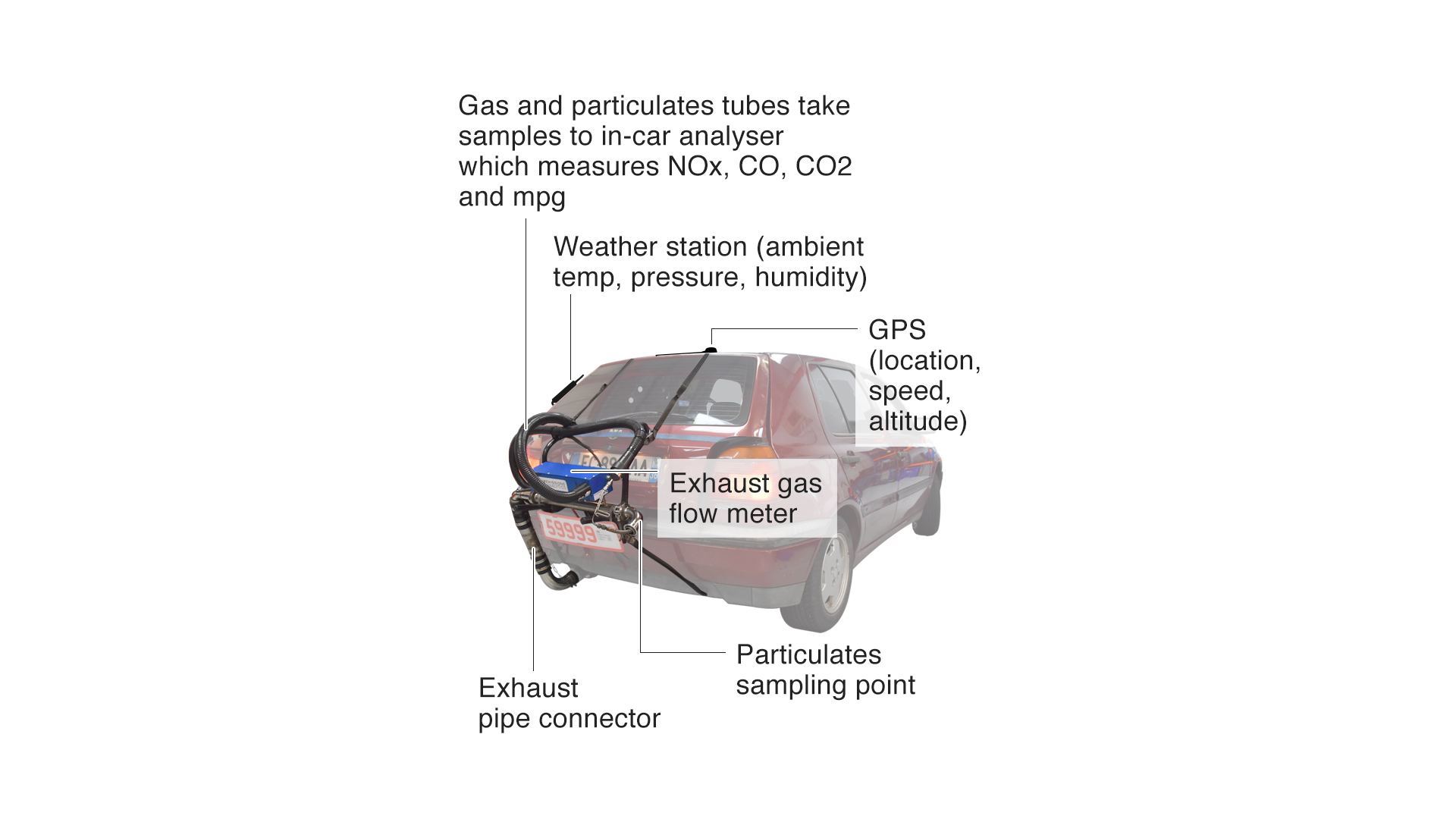

The best way of finding out what a car emits is to test it in real-world driving, with a PEMS - portable emissions measurement system.

This is the kit that a bunch of students and their lecturers at the University of West Virginia used to identify differences in what VW cars emitted in a lab and what they produced on the roads.

It led to dieselgate.

Very few people in the UK seem to have a PEMS kit though.

I assumed there would be a government-funded research centre to study vehicle emissions.

The closest I can find, though, is the Transport Research Laboratory, which in the 1970s invented the mini-roundabout, and was privatised in 1996. But they don't have a PEMS kit.

I do find two vehicle testing firms who regularly use PEMS.

The first discusses my request internally for a week before saying they don't have the capacity for “ad hoc emissions testing”.

An executive at the second company tells me, as an aside, that their clients are carmakers who don't want any potentially negative coverage of vehicle emissions.

I later discover that there is a body called the Vehicle Certification Agency that is responsible for vehicle type approval, including measuring fuel consumption and emissions. But they do not have their own centre, they use private contractors - the two companies I have just been talking to.

In the course of my enquiries I also discover the test is expensive.

No-one will give precise figures but it's somewhere between £3,000 and £10,000 per car. Due to the unique way the BBC is funded, this isn't going to work.

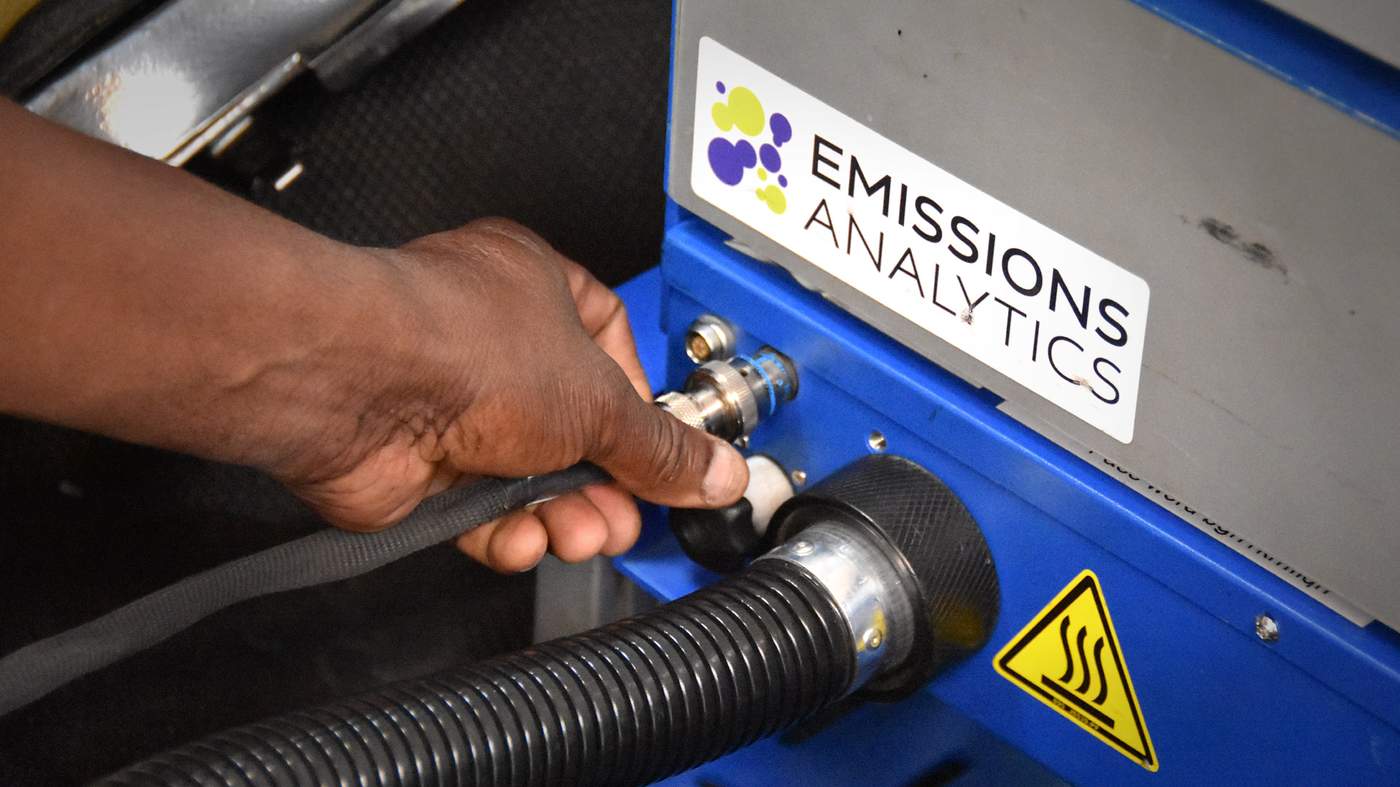

And then I hear about a small independent firm, Emissions Analytics, based in the Buckinghamshire village of Stokenchurch.

It was started in 2011 by an Oxford economics graduate called Nick Molden, who spotted what he calls “a market failure” caused by poor data.

Nick Molden

“The official statistics were leading people to buy the wrong car,” he says.

They were told it did 60mpg but in fact it did 40mpg.”

Not only that, the regulations were leading the manufacturers to build the wrong kind of car.

“They would meet the NOx limit in the lab but it would emit 10 times that when on the road. My mission was to create a new system that was real-world, accurate and independent.”

Today the firm tests 500 vehicles a year selling its emissions information to subscribers rather than working for the carmakers.

Being independent is their whole USP, Molden says.

That's how I find myself in a small hangar with metal roof, breeze block walls and a floor that squeaks when I reverse Melvyn into the narrow space where he will be fitted with the PEMS.

Watching the setting up of the test demands patience.

First Melvyn is emptied of all the detritus that has built up over my two-and-a-half years' ownership.

Then the rear seat is lowered and he is loaded with analyser boxes.

A weather probe and GPS emanate from his one operable rear window. GPS is needed to track his journey, including climbs and descents, and weather needs to be factored in to any results.

Heavy rain is a bigger problem and can stop the test as it can play havoc with the electrics.

Two engineers screw pipes into Melvyn's exhaust. They are then connected to two plastic tubes that look a bit like the kind you find on a vacuum cleaner.

Most of the exhaust emissions are released into the air but a small proportion will be measured.

One pipe goes into the gas analyser, the other into a machine called a CPN that measures particulates.

After about two hours, when it's all assembled, the mechanic hooks the pipes up to cylinders of various different gases and monitors the gas flowing through the system on a laptop.

It's a control to check everything's working.

In the back of the car a loud whirring noise comes from a fan used to cool the analysers, which get hot during the test.

How will Melvyn cope? He's been around Europe under a previous owner (a retired Australian gentleman called Melvyn, hence the name).

With Beth and me he has picked his way through the Pyrenees and made it to Galicia in north-west Spain. In all, he's clocked up more than 163,000 miles (262,675km).

I put the question to Steve Hayton, the project director.

A Golf Mk 3 like Melvyn is never going to be super clean but he could be OK, he says.

It's all down to how he's been serviced over the years.

And then it's time to go. Adam, one of the technicians, drives off in Melvyn, while I follow in a “chase car” driven by Lawrence, another technician.

It's a grey day as we set off but Melvyn makes a striking sight.

There are silver pipes and black plastic tubes climbing up his rear, some of which feed into a shiny blue box, and his boot - not fully closed - is held together by ties.

We arrive at a petrol station, carry out a quick check to make sure everything's working, then the test starts.

Nick Molden later tells me that several carmakers have tried to follow their test vehicle to identify the exact route. So I mustn't give too much away.

What can be said is that we mix up 20-minute sections - town, country and then motorway - to give an approximation of normal driving.

We move through High Wycombe's main roads and back streets, pausing in traffic and waiting for a white van to unload.

Soon it becomes leafier, we're passing semi-detached houses with paved drives, acacias and privet hedges.

Then we're out of the town and up to 50mph passing wheat fields, woodland and country pubs.

Next it's on to the M40 and the Chilterns. We're not far from the opening credits of Vicar of Dibley, Paul the photographer points out.

Melvyn is up to 70mph.

“That's a diesel,” says Lawrence pointing to a Peugeot van in the slow lane belching black smoke.

A petrol engine that's badly tuned produces blue smoke, he says. “But yours looks fine.”

We're off the motorway passing sheep, flint houses and village greens in places with names like Piddington.

Our speed fluctuates as we round corners and wait behind tractors. It's a far cry from those car advertisements of my youth that measured fuel consumption “at a constant 56mph”.

The next day we do it all again with the Skoda Octavia.

This time the sun shines, we talk about more than just emissions, and get to know rather a lot about each other's lives.

It's the camaraderie of a car journey.

At one point the radio bursts unexpectedly into life with Jon Bon Jovi singing “Woah, We're Half-Way There”.

It's Peter Kay's Car Share with a PEMS attached.

Two-and-a-half hours after the test began, the Skoda arrives back at the hangar.

The results won't be ready for a couple of days. So who will they favour - Melvyn or the Skoda?

At the time I'm only vaguely aware that they could have ramifications that point far beyond our father-son bet.

The moment of truth arrives in the form of an Excel document. Nick Molden is on the phone to talk me through it.

“Both cars have stats that are directly comparable with each other and our wider data set,” he begins. “Hopefully it's an interesting result.”

“Go on, then,” I think. It’s taken a long time to get this far, and the suspense is killing me.

First I must scroll horizontally across a document listing fuel efficiency, CO2 emissions, NOx and carbon monoxide emissions.

There are no values for the particulates here - those results have not come back yet, he says.

NOx is the big one. And there is a clear winner: the diesel.

Although diesels are castigated for being the big offenders as regards NOx, it’s not that simple.

In fact Melvyn emits three times more NOx than the Skoda - 0.798 grams per kilometre as opposed to 0.260g/km.

The urban/rural/motorway breakdown shows that both cars produce more on the motorway than in the other two settings, which perhaps isn’t surprising as they are going faster and working harder.

Nitrogen oxides are at their most dangerous in built-up areas where people breathe them in higher concentrations.

Melvyn, a VW Golf GL 1.8, performed a little better in urban driving than he did in the other two parts of the test. But at 0.678g/km his reading is still more than two-and-a-half times worse than the 0.262g/km registered by the Octavia Elegance 1.9.

Melvyn's carbon monoxide value is high too. In urban driving it is 3.804g/km - “very poor” by today's standards. But his overall figure of 2.499g/km, taking into account his performance in other parts of the test, means he is still legal. Just.

Diesels do not emit much carbon monoxide and the Skoda's urban figure is just 0.014g/km.

On fuel economy the Golf posts 34.0 miles per gallon against the Skoda's 50.5mpg.

The national average for Euro 6 (post-autumn 2014) petrol cars is 35.6mpg so Melvyn is only a little way behind.

For diesel cars it’s 45.0mpg. A side-effect of this is that they produce less CO2, so there was some logic in Gordon Brown’s measures to promote the sale of diesels.

I'm relieved to say that neither car is breaking the law. But at the same time, neither would be allowed to be sold new today if these results were obtained in lab conditions.

And here it gets interesting. In fact it gets downright controversial.

Nick clears his throat.

“The average real-world [NOx] emissions from our Euro 6 diesels that we've tested is currently 0.399g/km. The Skoda is about a third less than the current average.”

I ask him if I've understood correctly. My dad's 2009 car emits less NOx than most new diesels they've tested in the past three years?

Yes, a third less, he says. So how come they are legal if the Skoda would not now pass the legal limit?

Here's the tricky bit. The limit on NOx for Euro 6 diesels is 0.08g/km. My dad's Skoda comes in at 0.262g/km.

In other words, more than three times today's limit. But it is still better than most modern diesels.

Something doesn't add up here. And it's all down to the testing.

The new diesels pass the 0.08g/km figure in the lab. Like a child coached to pass an exam they do well in controlled conditions. But out in the real world they struggle.

Some of them emit many times the European limit.

I dig into the Equa Index, produced by Nick Molden’s company, which gives cars ratings from A to H.

Having looked at the data for cars tested in 2016 and 2017, I request the exact NOx figures for some of the more surprising scores. And what comes back is pretty shocking.

Here are two examples:

~ The Renault Megane Experience (1461cc) produces 0.991g/km - 12 times the limit (made in 2016, tested in January 2017)

~ The Fiat 500X CityLook Popstar (1598cc) produces 1.153g/km - 14 times the limit (made in 2015, tested in December 2015)

But the worst is the Nissan Qashqai, which last month overtook the Ford Fiesta to become the UK's most registered car (counting diesel and petrol models together).

The Qashqai N-Connecta DCI CVT (1598cc) produces 1.46g of NOx per kilometre. That is more than 18 times Europe's 0.08g/km limit.

It's almost twice Melvyn's score.

Five of my dad's Skodas would produce less NOx than this version of the Qashqai.

Asked to comment on this poor result, Nissan replied: “Nissan is committed to upholding the law and meeting or exceeding regulations in every market where we operate. All our vehicles sold in Europe meet the Euro 5/6 emission standards.”

Renault said all of its vehicles complied with the laws and regulations of the country in which they were sold, adding that it was aware of “significant potential for improvement regarding the release of nitrogen oxides (NOx) in real use conditions”. The company said it had been gradually taking action to reduce the gap between the performance of its vehicles in the lab and on the road, for example by reprogramming their engine injection computer.

The Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT) said carmakers were investing billions in low-emission technologies to help improve air quality, adding it that it couldn’t comment on “non-official tests”.

But how can it be that some new diesels are so dirty? Haven't they improved at all since my dad's car left the factory in 2009?

Molden explains that there is a huge range. While most petrol cars leave diesels far behind when it comes to NOx some new diesels are relatively clean and some are very dirty.

I look again at the list.

It's true the Mercedes C250 AMG Line Premium DA

produces 0.080g/km of NOx in real-world driving, so it complies with the regulations outside the lab as well as inside.

A version of the VW Tiguan (the SE-L BiTDI SCR 4MOTION Blue Motion Technology, to give it its full name) even comes in at 0.076g/km, just below the 0.08g/km limit.

Both cars produce less than a third of the amount of NOx that my dad's Skoda emits. But they are a rarity.

So why are diesels managing to pass strict limits in the lab while producing high levels of emissions on the road?

It’s all down to the New European Driving Cycle - the laboratory process in place in Europe since 1997 - says Anup Bandivadekar, passenger vehicles director at the International Council on Clean Transportation.

This puts cars through a test involving steady acceleration, constant speed driving and steady deceleration. It bears no relation to how people actually drive, Bandivadekar says.

This narrow focus has made it easy to game the system, he says.

Auto makers rather than trying to meet the spirit of the regulations are trying to meet the letter of the law.

“There doesn't seem to be enough incentive to do the right thing so companies are doing the bare minimum. That's the crux of this. The technical reasons are multiple.”

There is one big disappointment about the Skoda's test results, I discover a couple of days later - it proved impossible to get an accurate measurement of the particulates emitted.

Molden is happy to say that Melvyn emitted a negligible quantity of particulates whereas the Skoda emitted more, but due to a technical problem I cannot publish the exact value.

So what does the test show?

Quite a lot, it seems to me.

That a diesel can be better for NOx than an old banger with a petrol engine.

That older diesels can beat newer ones.

That the European testing regime failed at some point in the last decade.

And that the Euro 4, 5, 6, designations are misleading.

Belatedly, the authorities have woken up to the problem of misleading lab tests. Last month the European Union began its Real Driving Emissions (RDE) test on all new cars.

The SMMT describes the new EU testing regime as the “toughest in the world”.

But it is not retrospective, so all the millions of diesels labelled as compliant with the Euro 6 standard on the basis of a flawed lab test are still out there pumping out high levels of NOx.

And in Bandivadekar’s view, the RDE test is too lenient. The way it defines “real” driving is still too simplistic, he argues.

In addition, until 2019 carmakers will be given leeway of 2.1 times the European limit - diesel cars will be allowed to emit 0.168g/km instead of 0.08g/km.

After that they will be given leeway of 1.5 times the limit. This is partly because there is some variability in the results of the PEMS test.

The new T Charge arrives next week in London. It will quite rightly penalise my Golf. I'll have to pay £10 to drive into the central London congestion charge zone, in addition to the standard charge.

But no-one is stopping me from driving round my built-up area of south-east London.

Meanwhile the Skoda, as a Euro 4 car, will not be penalised by the T Charge.

But the next big change, the Ultra Low Emission Zone due to come into force in London in 2019, will penalise Euro 4 cars and older.

At the same time it will permit the Euro 6 diesels like the Nissan Qashqai N-Connecta DCI CVT to pump out NOx at 18 times the European limit.

It all seems very arbitrary.

Some cities - Oxford and Paris - have set ambitious targets on banning all combustion engines.

Problem sorted?

Not according to Prof Frank Kelly, the man whose lecture helped change my dad's mind. Even electric vehicles produce particulates from wear on brake discs and tyres, and by throwing up dust on roads.

In any case it seems unlikely that petrol and diesel vehicles will vanish in the next five or 10 years.

In which case there's a desperate need to sort the wheat from the chaff, the Tiguans from the Qashqais.

In a bid to do this the Mayor of London’s website is now going to publish Emissions Analytics’ Equa Index on its website.

When I phone my Dad to discuss the results, he's magnanimous in victory and agrees to accept a half rather than a pint because of the Skoda's higher particulates.

He says he is pleasantly surprised by the Skoda's NOx levels. But it's not enough. “I'm going to get rid of it,” he says.

It's partly because it's getting old. But he's also done some soul searching.

He worries about the particulates and the NOx in the city, so hopes to find a buyer who lives in a rural area.

His next car?

I wouldn't buy another diesel. I'm wondering about an electric car, but the problem is range. So I'm tempted more by a hybrid.”

And what of Melvyn?

Eight days after the test I get a call from Beth saying that clouds of steam are billowing from his bonnet and she's been forced to park in a cul-de-sac 10 minutes from home.

It turns out to be a broken radiator hose and he's soon back on the road again.

But we've made up our mind to have him scrapped. He is 13 times over the NOx limit for a new petrol car after all.

It'll be sad to say goodbye. He's only my second ever car. We've been to a lot of places together.

He's carried our daughter Hannah in the first six months of her life. But he's dirty and the world will be better off without him.

We probably won't replace him - we only bought him to move out of London, and now we're back.

It's easy for us to be ethical - Melvyn cost just £950.

If you've spent £19,000 on a Nissan Qashqai diesel it'll be rather harder to take a stand to help clean up the air we breathe.