About eight miles from Penzance, down one of those narrow, winding country lanes Cornwall is notorious for, lies Gwynver beach.

Many will drive past without realising it is there, bound instead for the fishing village of Sennen or the tourist attraction of Land's End.

But those who make the turn, opposite a chapel featuring a cross formed by two surfboards, will be rewarded.

On a fine day, Gwynver could pass for paradise.

A stretch of blindingly bright sand caressed by the blue Atlantic. A curved cliff envelops the beach like a pair of protective wings.

Out to sea, trawlers chug along. The waves are dotted by surfers, undeterred by a smooth swell, their wetsuits shining black, their boards a grainy white.

Gwynver was Jacob’s spiritual home.

It was here he surfed and held late-night barbecue parties.

It was here his friends gathered the day after his death to light fires and release lanterns.

It was here his ashes were scattered along with those of his sister Grace.

Jacob's existence was one of exhilaration, excitement and risk.

Whether dancing at all-night raves, surfing impossible waves or exploring crystal-filled caves, Jacob attacked life full throttle.

"He had these crazy eyes that looked like the sea, his hair was always unkempt, he always looked happy," says his friend Barnaby Courtney.

"He made you believe magic existed."

Jacob grew up just outside Penzance and, although he travelled the world, he only felt truly at home in the town and the beaches that surround it.

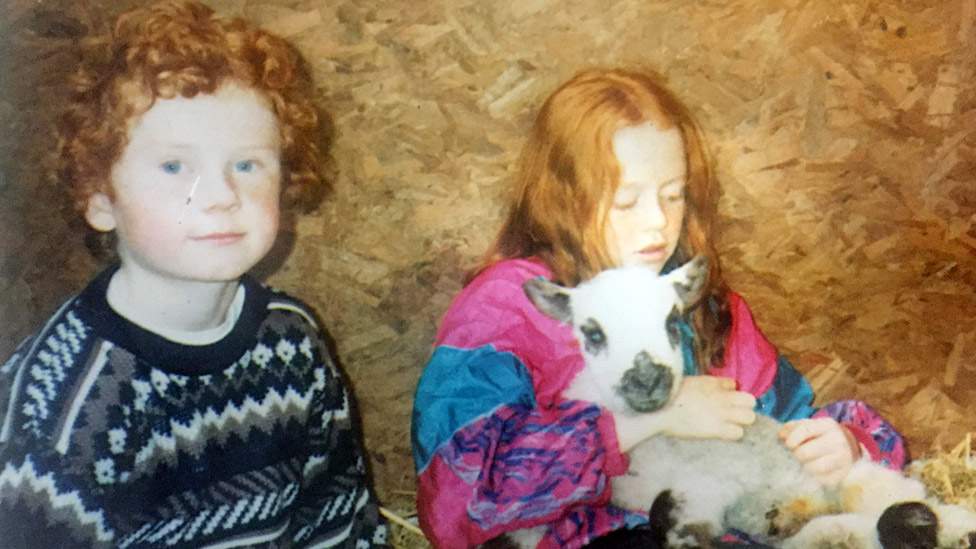

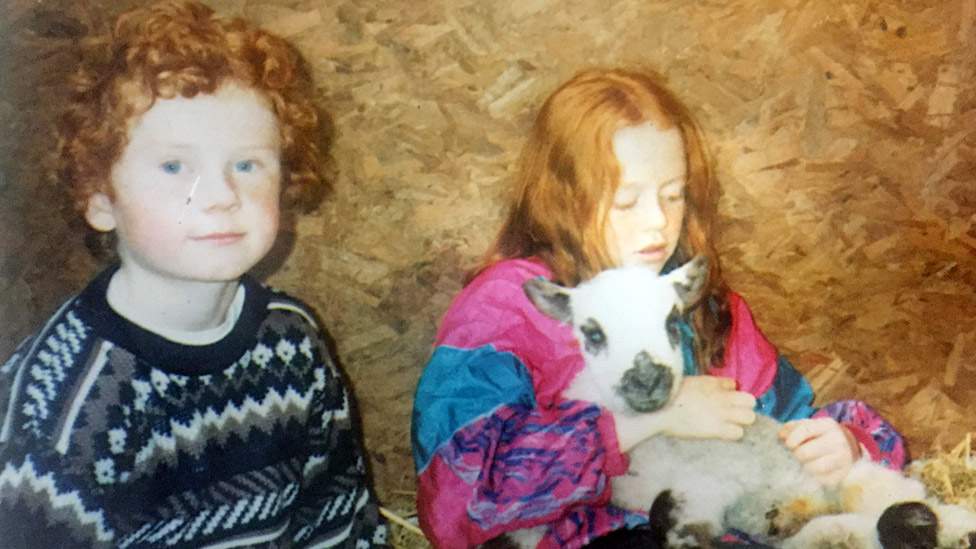

It was a quintessential Cornish childhood. Days were spent running around the countryside or bathing at the beach.

Children were tanned or pink from days in the sun, or bundled up in Quiksilver coats against the murky mist that often smothered the land.

"Jacob loved the water," his mother Carolyn says. "Once he was in you could never get him out."

Diagnosed with dyslexia when he was 10, school was a struggle.

He would skip lessons with his friends to hitchhike to the beach, surfboards beneath their arms.

Grace was the polar opposite of her brother - a star pupil.

She worked hard, consistently scored top marks and was a champion at netball, hockey and cross country.

"Grace was great," says Paul Kellas, Jacob’s form tutor at Cape Cornwall Comprehensive and now the school's assistant head teacher.

He smiles at his memories of her but the smile fades.

"What happened to her, well, it was heartbreaking.

"What more does that poor family have to go through?"

Jacob was the youngest of four children, the baby brother to Grace, Laura and Joe. But he was closest to Grace, three years his senior.

When he was a toddler the pair devised a secret language and she would always speak for him.

In fact people thought Jacob had a problem.

"They were genuinely worried that he didn't know how to talk," says his older sister Laura.

"But I said of course he knows how to talk, it's just he doesn't need to, Grace does it for him."

As Jacob grew older, his closeness to Grace remained.

"She was really bright but also really driven and determined; if she wanted to achieve something she did," says her best friend Dabriella Quayle.

"She was the sort of girl your parents talked about, 'why can't you be more like Grace'?"

Dabriella’s twin sister Aprilla nods in agreement.

"She was very headstrong, but she was also fun.

"She was older than her years, she had the sense of someone in their 30s or 40s."

The twins pause.

"Looking back now it was eerie," says Aprilla.

"Almost as if Grace knew she had limited time so had to excel and do everything."

We thought through it all she was going to survive."

The headaches had begun in the summer of 2001 while Grace was on a gap year working at children's camps in France.

She came home in the August and was diagnosed with a brain tumour in September.

Grace underwent radiotherapy at the Derriford Hospital in Plymouth, her family camping nearby throughout.

However, Jacob stayed at home.

"Because he was younger we did not tell Jacob a lot of what was happening," says his mother.

"We thought through it all she was going to survive."

After six months Grace's cancer returned and her only hope was an operation in Belgium.

Grace went to Belgium, the operation was only a partial success. The tumour returned.

This time it was terminal. Grace died on 18 December 2002. She was 20.

After her death, Grace's ashes were stored in the airing cupboard, her "favourite place in the house".

She had asked for them to be kept until another family member died.

She had been afraid of being scattered alone. It surprised Dabriella.

"I thought it was a very strange request for her," she says.

"She had always been such an independent person, it was just very un-Grace."

Eleven years later, following the death of her grandmother, arrangements were finally being made to scatter their ashes together.

Then, a day before the planned ritual, Grace's younger brother died.

She was no longer alone.

Jacob was the youngest of four children, the baby brother to Grace, Laura and Joe. But he was closest to Grace, three years his senior.

When he was a toddler the pair devised a secret language and she would always speak for him.

In fact people thought Jacob had a problem.

"They were genuinely worried that he didn't know how to talk," says his older sister Laura.

"But I said of course he knows how to talk, it's just he doesn't need to, Grace does it for him."

As Jacob grew older, his closeness to Grace remained.

"She was really bright but also really driven and determined, if she wanted to achieve something she did," says her best friend Dabriella Quayle.

"She was the sort of girl your parents talked about, 'why can't you be more like Grace'?"

Dabriella’s twin sister Aprilla nods in agreement.

"She was very headstrong, but she was also fun.

"She was older than her years, she had the sense of someone in their 30s or 40s."

The twins pause.

"Looking back now it was eerie," says Aprilla.

"Almost as if Grace knew she had limited time so had to excel and do everything."

We thought through it all she was going to survive."

The headaches had begun in the summer of 2001 while Grace was on a gap year working at children's camps in France.

She came home in the August and was diagnosed with a brain tumour in September.

Grace underwent radiotherapy at the Derriford Hospital in Plymouth, her family camping nearby throughout.

However, Jacob stayed at home.

"Because he was younger we did not tell Jacob a lot of what was happening," says his mother.

"We thought through it all she was going to survive."

I thought it was a very strange request for her."

After six months Grace's cancer returned and her only hope was an operation in Belgium.

Grace went to Belgium, the operation was only a partial success. The tumour returned.

This time it was terminal. Grace died on 18 December 2002. She was 20.

After her death, Grace's ashes were kept in the airing cupboard, her "favourite place in the house".

She had asked for them to be kept until another family member died.

She had been afraid of being scattered alone. It surprised Dabriella.

"I thought it was a very strange request for her," she says.

"She had always been such an independent person, it was just very un-Grace."

Eleven years later, following the death of her grandmother, arrangements were finally being made to scatter their ashes together.

Then, a day before the planned ritual, Grace's younger brother died.

She was no longer alone.

Jacob was 17 when Grace died and her death had a devastating impact on him. It changed his view of life. He believed her energy transferred into him.

This inspired him to "throw everything to the wind and give it a try," his girlfriend Rachel says.

"He thought, as a young beautiful woman she did not do anything in life to deserve that, there was no karma to it, it was just cruel.

"He felt like he needed to live his life for her as well as for himself.

"Maybe that's why he lived his life twice as hard."

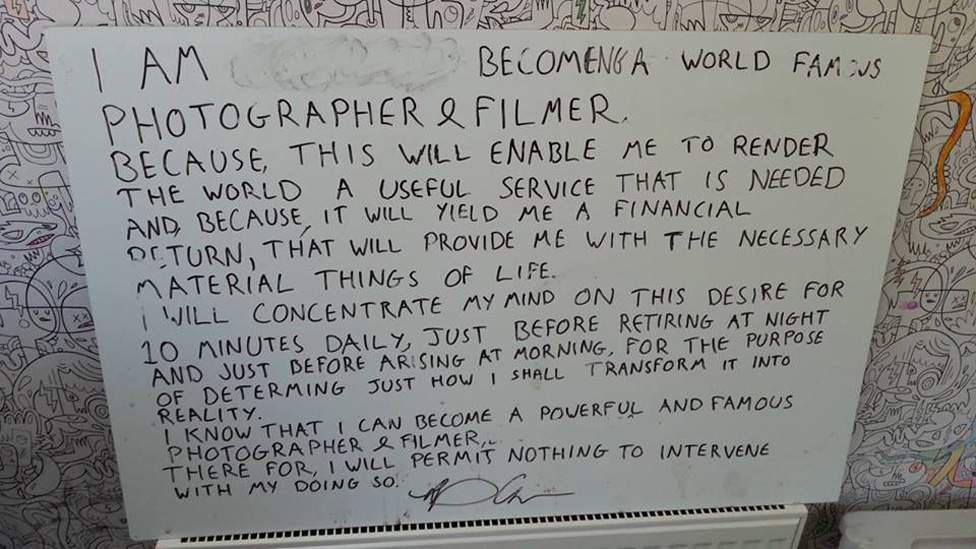

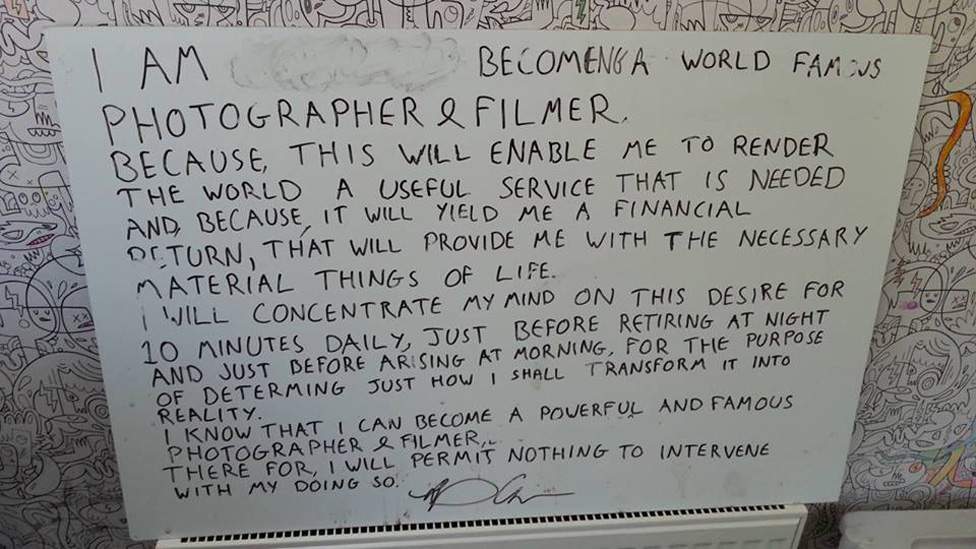

On a board in his bedroom, a teenage Jacob had laid bare his ambition.

"I am becoming a world famous photographer and filmer," he had written.

"I will concentrate my mind on this desire for 10 minutes daily for the purpose of determining just how I shall transform it into reality.

"I will permit nothing to intervene with my doing so."

The photography normally went hand in hand with his other obsession - taking risks.

He would usually be armed with a camera during each daredevil escapade and was prepared to do anything to get the best shots.

Jacob pushed himself to greater extremes. He taught himself to hold his breath for long periods so he could explore the depths.

He would also surf over rocks or towards cliffs.

The danger of it all was part of the draw.

"He and his friends dared to surf where others did not," says Gary Richards, a friend who had known Jacob since babysitting him.

"They wanted to catch the bigger waves and do bigger tricks."

After he and his friends surfed a storm in Newlyn in 2008, numerous national newspapers splashed with this photograph showing Jacob moments before he was struck by a huge wave.

A regular stunt was to throw himself from tall buildings into the water below, such as the three-storey Abbey Warehouse in Penzance harbour.

He received a police caution after leaping from a railway bridge in Hayle.

And on another occasion, he jumped into the harbour outside Bosun’s Locker Nightclub in Penzance and had to be rescued from being crushed by a ship.

Zain Ishmael was one of those who came to his aid, forming a four-man human chain with his friends to pull a jubilant Jacob to safety.

Everyone cheered, Jacob laughed and then just ran off into the night.

"What a crazy cat," Zain recalled.

Jacob was 17 when Grace died and her death had a devastating impact on him. It changed his view of life. He believed her energy transferred into him.

This inspired him to "throw everything to the wind and give it a try," his girlfriend Rachel says.

"He thought, as a young beautiful woman she did not do anything in life to deserve that, there was no karma to it, it was just cruel.

"He felt like he needed to live his life for her as well as for himself.

"Maybe that's why he lived his life twice as hard."

Jacob’s hyperactive energy found an outlet in his obsession with photography.

On a board in his bedroom, a teenage Jacob had laid bare his ambition.

"I am becoming a world famous photographer and filmer," he had written.

"I will concentrate my mind on this desire for 10 minutes daily for the purpose of determining just how I shall transform it into reality.

"I will permit nothing to intervene with my doing so."

The photography normally went hand in hand with his other obsession - taking risks.

He would usually be armed with a camera during each daredevil escapade and was prepared to do anything to get the best shots.

Jacob pushed himself to greater extremes. He taught himself to hold his breath for long periods so he could explore the depths.

He would also surf over rocks or towards cliffs.

The danger of it all was part of the draw.

"He and his friends dared to surf where others did not," says Gary Richards, a friend who had known Jacob since babysitting him.

"They wanted to catch the bigger waves and do bigger tricks."

After he and his friends surfed a storm in Newlyn in 2008, numerous national newspapers splashed with this photograph showing Jacob moments before he was struck by a huge wave.

A regular stunt was to throw himself from tall buildings into the water below, such as the three-storey Abbey Warehouse in Penzance harbour.

He received a police caution after leaping from a railway bridge in Hayle.

And on another occasion, he jumped into the harbour outside Bosun’s Locker Nightclub in Penzance and had to be rescued from being crushed by a ship.

Zain Ishmael was one of those who came to his aid, forming a four-man human chain with his friends to pull a jubilant Jacob to safety.

Everyone cheered, Jacob laughed and then just ran off into the night.

"What a crazy cat," Zain recalled.

By his early 20s, he had won awards from National Geographic and The Sunday Times.

He was a regular contributor to surf magazines, often providing the much-coveted cover shot.

Most of his pictures featured the sea. His shot of a fishing boat returning to port in a large swell won a competition to appear on posters on the London Underground.

Weeks before his death, he won a £28,000 expedition to Antarctica, the adventure of a lifetime.

Jacob's shot of his friend Seb surfing near a supertanker in Sumatra was the winning image in a travel photography contest run by The Guardian.

Judges said the picture would "stand the test of time".

As well as being a stunning photograph it also epitomised his ethos - the shoot had been "extremely dangerous", according to Jacob.

Waves bouncing off the great hulk of the hull were wildly unpredictable and just below the surface there were great twists of metal waiting to skewer the unfortunate.

Another photograph Jacob entered for the same competition won a photograph of the month prize for August.

A selfie of him and his friends partying in a small Cornish pub, its magic-of-the-moment unbridled joy and energy was typical of his style.

"His career was photography but that encompassed so much of what he found important in life," says Rachel.

"Everything he did was in symbiosis with the way he lived his life. It was all kind of one big experiment."

The money he earned was quickly spent on new photography gadgets. Prizes, such as a new television, were typically given away to friends.

He won expeditions, stays in fancy hotels, exhibition space.

One contest saw him win a pair of custom design Nike trainers which he called the Yak 2000, Yak being one of the various nicknames he was known by.

He sought new experiences and wanted to capture them all with his camera.

One of these was close to his home. It seemed to offer the perfect combination of excitement and visual art.

It was the whirlpool.

The vortex in Hayle harbour only appeared a few times a year.

It was a quirk of Victorian engineering devised to stop the harbour silting up.

Water would be stored in a pool at high tide and, once the tide had retreated, released back into the harbour to wash away the sand.

The water would get into the pool through a tunnel beneath a quay.

But once every spring tide the sea would come back in faster than the water could pass through the tunnel.

This would create the whirlpool.

The swift-swirling vortex appealed to Jacob's adventurous spirit and enticed him in.

Ignoring the warning signs placed around the sluice, he would swim with the whirlpool and film it.

Jacob posted the videos on YouTube where they were watched millions of times, making him hundreds of pounds.

The videos are beautiful and hypnotic.

They are also terrifying.

It was 28 May 2013 when the whirlpool returned.

Artist David Raine, who had collaborated with Jacob in the past, was in his living room when he saw his friend running towards the house.

Jacob was excited, already wearing his wetsuit and clutching his camera.

David agreed to film him as he swam around the whirlpool.

By the time he reached the harbour, Jacob was already in the water.

He was wearing a rubber horse’s head, a prop he thought would make the video more eyecatching on YouTube.

Jacob had already shot a lot of footage but while the whirlpool was there he wanted to make the most of it.

David filmed from the quay as a whooping Jacob swirled around the whirlpool's edge.

"It looks a powerful one," David called to Jacob.

"Ah yeah, earlier on it was really scary," Jacob shouted back.

"It's fine now because it's so deep but when I first got in I was a bit scared to be honest.

"It's safe as now, though."

He let the whirlpool carry him around again. It caught Jacob, tugging him down.

"Woah woah," he cackled as he escaped the drag.

"That was pretty scary."

He asked David to pass him a GoPro camera attached to a short pole.

Jacob wanted to get one last shot below the surface.

Jacob dived down.

David watched. Jacob did not reappear.

David began to worry. He called his friend's name.

David ran across to the other end of the quay where the tunnel the whirlpool funneled into flowed into a pool.

He asked a fisherman if he had seen anyone come through, but he hadn't.

There was a grill in the ground through which he could see the water churning through the tunnel below. But there was no sign of Jacob.

David ran back and forth. Then he saw him.

Jacob was in the pool, the tunnel had spat him out. He was floating in the water, face down.

David waded out to him.

He knew it was too late.

The vortex in Hayle harbour only appeared a few times a year.

It was a quirk of Victorian engineering devised to stop the harbour silting up.

Water would be stored in a pool at high tide and, once the tide had retreated, released back into the harbour to wash away the sand.

The water would get into the pool through a tunnel beneath a quay.

But sometimes the tide would come back in faster than the water could pass through the tunnel.

This would create the whirlpool.

The swift-swirling vortex appealed to Jacob's adventurous spirit and enticed him in.

Ignoring the warning signs placed around the sluice, he would swim with the whirlpool and film it.

Jacob posted the videos on YouTube where they were watched millions of times, making him hundreds of pounds.

The videos are beautiful and hypnotic.

They are also terrifying.

It was 28 May 2013 when the whirlpool returned.

Artist David Raine, who had collaborated with Jacob in the past, was in his living room when he saw his friend running towards the house.

Jacob was excited, already wearing his wetsuit and clutching his camera.

David agreed to film him as he swam around the whirlpool.

By the time he reached the harbour, Jacob was already in the water.

He was wearing a rubber horse’s head, a prop he thought would make the video more eyecatching on YouTube.

Jacob had already shot a lot of footage but while the whirlpool was there he wanted to make the most of it.

David filmed from the quay as a whooping Jacob swirled around the whirlpool's edge.

"It looks a powerful one," David called to Jacob.

"Ah yeah, earlier on it was really scary," Jacob shouted back.

"It's fine now because it's so deep but when I first got in I was a bit scared to be honest.

"It's safe as now, though."

He let the whirlpool carry him around again. It caught Jacob, tugging him down.

"Woah woah," he cackled as he escaped the drag.

"That was pretty scary."

He asked David to pass him a GoPro camera attached to a short pole. Jacob wanted to get one last shot below the surface.

Jacob dived down.

David watched. Jacob did not reappear.

David began to worry. He called his friend's name.

David ran across to the other end of the quay where the tunnel the whirlpool funneled into flowed into a pool.

He asked a fisherman if he had seen anyone come through, but he hadn't.

There was a grill in the ground through which he could see the water churning through the tunnel below. But there was no sign of Jacob.

David ran back and forth. Then he saw him.

Jacob was in the pool, the tunnel had spat him out. He was floating in the water, face down.

David waded out to him.

He knew it was too late.

That night, Carolyn was in bed when the police arrived at her home.

She was taken to Treliske Hospital in Truro to identify her son.

She was so shocked she could not even cry.

When she got home her house was full of people. It would remain so for days, a stream of mourners washing through.

Jacob's funeral was a major event. The church could not accommodate all of the people who wished to attend.

His coffin was painted with a wave motif and his body was dressed in his hole-riddled pants, shorts and favourite hat.

Afterwards, about 40 of his friends did what they thought Jacob would have wanted them to; they went skinny dipping in Penzance's open-air, sea-filled pool The Jubilee.

Shortly after Jacob’s death, Carolyn moved out of Penzance. She just had to.

"I would go to the supermarket and I would have people I did not even know coming up to me crying and hugging me," she says.

"We had to get away so we moved here."

Home is now an old farmhouse near Sennen, on the other side of a hill from Land's End airport.

I do not think he was scared of death."

A few fields away is Gwynver, where Grace and Jacob’s ashes were scattered.

Carolyn has transformed part of her garden into a shrine.

At the top sits a statue of the Buddha. Buried beneath are the sunflowers from Grace's bedroom window and the dreadlocks which adorned Jacob's head.

His surfboard stands in the front garden, next to the A30.

Five years after he died, surfers bound for the nearby beaches and coves still honk their horns as they drive past.

Inside, almost every wall is covered by Jacob’s photographs or paintings.

"He won every award going," Carolyn says proudly.

But his absence is still being felt, she adds.

"There is never a day that I don't think about it."

A year after Jacob's death, the sluicing system in Hayle harbour was altered. It meant the whirlpool which had fascinated and ultimately killed Jacob vanished forever.

Most agree if Jacob had survived the whirlpool it would not have changed his approach to life, though.

"I do not think he was scared of death," says Rachel.

"If he was going to go any way it was going to be in some extreme blaze of glory like that.

"Like he was vortexed into the next realm."

His friend, Barnaby Courtney, agrees.

"When I heard how he died I felt full of grief but it felt like if he had to go, that was the just way," he says.

"I mean really, what a ridiculous, almost hilarious, way to pass on. He'd have thought so.

"Going down a whirlpool?

"It's like something out of a fairy tale."