By Jessica Lussenhop

Hesperia, California, is a dusty city of fewer than 100,000 people in the Mojave Desert, about a two-hour drive northeast of downtown Los Angeles. Far from the glitz of Hollywood, it’s a city of squat houses with high chain-link fences surrounding dirt yards. The purple snow-capped San Bernardino mountains loom on almost every horizon.

On the week I visited, a big white tent was selling freshly cut Christmas trees in a vacant lot between a Chevron station and a Wendy’s fast-food restaurant. The smell of pine sap hovered over the arid plateau.

I’d come to the High Desert because it’s the home of one of the internet’s most recent - and most reviled - viral stars: Jered Threatin, a hard rock musician who performs simply under the name “Threatin”.

A month earlier, Threatin had become an international laughing stock, after a small army of internet sleuths revealed that he had tried to fake his way to stardom using paid Facebook likes, YouTube views and bots.

He had uploaded deceptively edited film footage that appeared to show him playing to sold-out crowds, lied about a non-existent award and album sales, completely fabricated an entire US tour, and used it all to secure a 10-city tour of Europe and the UK.

As it would turn out, that was all just the tip of the iceberg.

By the end of it, his bandmates had abandoned him, his final stops in France, Italy and Germany were cancelled, and the internet was in a frenzy over the young man’s downfall.

“The guy’s clearly a delusional rich kid,” scolded a commenter on one of the dozens of articles that helped unravel the hoax.

“A simple conman,” read another. “I'm surprised he hasn't gotten the hell kicked out of him yet. I'll do it for free.”

His own brother, Scott, an extreme metal musician still living back in their hometown of Moberly, Missouri, had warned me not to bother coming to California to speak to his now-infamous younger sibling.

“It's all smoke and mirrors with Jered,” he wrote to me via Facebook. “He'll lead you to believe there’s something big to get you to bite... only for you to be let down. Be careful.”

Scott went as far as to wonder if Jered might rent out some kind of party mansion in anticipation of my arrival, to convince me that he really was an international rock star. But my GPS instructions led me to an ordinary-looking, single-storey house on the side of a thunderous four-lane freeway lined with fast-food restaurants and superstores.

When I rang the doorbell, a woman with long reddish-blonde hair and librarian’s glasses answered the door. It was Kelsey, Jered’s wife. I recognised her from her Instagram account, which had briefly gone dark as the internet mob descended upon her, demanding to know her level of complicity in her husband’s scam.

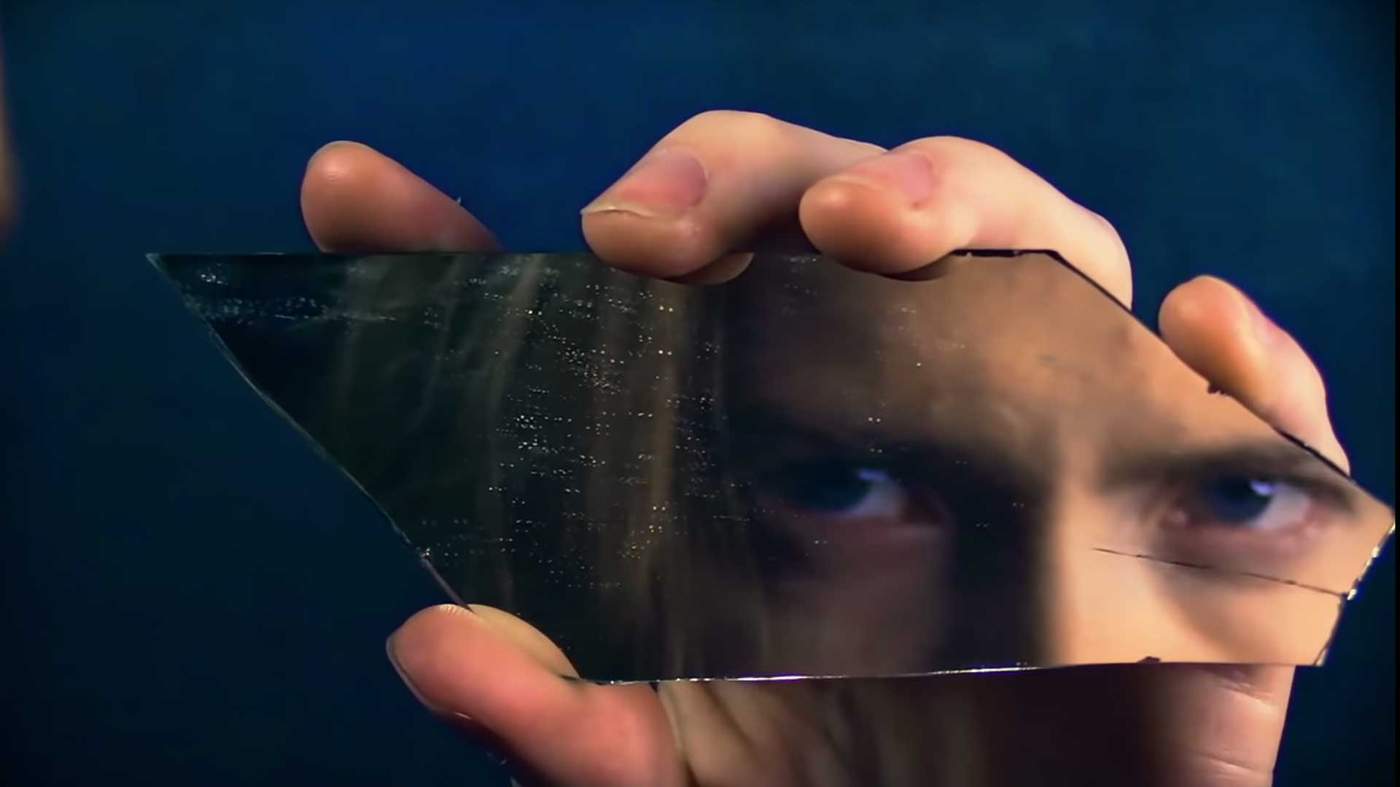

Threatin - whose real name is Jered Eames - stepped into the hallway behind her. The 29-year-old was shorter than I expected, about 5ft 9in (1.75m), wearing the same black leather motorcycle jacket he wore in his promotional photos over a black T-shirt and black trousers.

He has one of those ageless faces that would make you believe he was either 19 or 50, depending on what you were being told. His distinctive hair cascaded down his back.

“Nice to meet you,” he said, extending a pale hand. “I’m Jered. But you know that.”

As we briefly toured the Eames’ immaculate and sparsely decorated home - framed portraits of Jered hung throughout, rows of identical black T-shirts and cargo pants hung in the walk-in wardrobe - I still didn’t know what to expect. Would he be defensive? Apologetic? Was he embarrassed or oblivious?

Over the many hours of conversation that followed, I discovered that he was none of these things. Even all the cunning of internet detectives hadn’t been able to fully uncover the truth behind Jered Threatin, and the strange and sparklingly unique trainwreck that was the Breaking the World Tour.

When I told him point blank that there was no way I could completely trust what he was telling me, he was unperturbed.

“I understand that,” he shrugged. “That’s part of the fascination.”

Weeks earlier, when the immolation of Threatin was in full effect, even the people he had tricked into supporting his disastrous bid for fame had to give him credit - the attempt was impressive in both its intricacy and its audacity.

“This whole thing is just surreal,” said Rob Moore, lead singer of the band Dogsflesh, which opened for Threatin on one of the early tour stops. “He’s basically duped the whole of the music industry. He’s duped everybody, myself included.”

Months before Threatin boarded a plane bound for Heathrow, London, material sent out to venues and prospective support bands claimed that Eames had “signed to SPV Records (Whitesnake, Scorpions, Motorhead)” and that his “last single charted Top 40 in 7 countries”.

“The world rarely sees so much talent wrapped into one person,” read his website, alongside photos of a wan young man with long, straw-coloured hair glowering into the camera.

The site reported sales of more than 55,000 copies of his debut EP. His Facebook page had nearly 40,000 likes and his YouTube channel was filled with clips of Threatin playing to packed arenas of screaming fans.

“I would let Jered Threatin do literally ANYTHING to me!” one of dozens of fan comments gushed.

It was this kind of online fandom that helped convince guitarist Joe Prunera that playing with Threatin might be the kind of break he’d been waiting for.

It began with a Facebook friend request from someone named Lisa Golding. Prunera, a 36-year-old AV technician at the Wynn Las Vegas resort and casino, had moved out West years earlier with aspirations of a career in music, and noticed immediately that Golding was an agent with a company called Aligned Artist Management based in Beverly Hills.

As soon as he approved her request, Golding sent Prunera a message.

“We have a signed hard rock artist on our roster that is looking for a new rhythm guitarist for their upcoming tour in Europe this November,” Golding wrote. “If you are interested I would like to set you up with an audition/meeting with the band in Los Angeles.”

Prunera immediately called the number at the bottom of the message, spoke to Golding, and agreed to make the four-hour drive for the audition. A second employee of Aligned Artist Management named Joe Abrams took care of the logistics via email, writing that while the tour would pay only $300 (£239) in total, all Prunera’s expenses would be covered for the two-week itinerary.

On 21 July, Prunera arrived on the Sunset Boulevard location of SIR Studios. When he texted Golding to tell her he’d arrived, it was Kelsey who met him and walked him back to the rehearsal studio where Jered was waiting.

“He was very down to earth, very nice and easy to get along with,” recalled Prunera. “My initial thought was this is someone I could actually see myself hanging out with.”

At dinner that night, Eames offered Prunera the job. For someone who’d put some of his own rock star dreams on the back burner to make ends meet, it felt like a great opportunity. The fact that he’d never heard of Threatin didn’t bother him.

“I was thinking: ‘OK, he’s a signed artist, he’s got a label behind him, a manager, a promoter.’ I’m thinking that he’s not huge, but he’s on his way,” said Prunera.

Threatin also hired bassist Gavin Carney, a local from outside LA, and Dane Davis, a drummer based in Las Vegas. All three were approached by Golding and Abrams, who’d found their videos on YouTube. None of the band members ever met anyone from Aligned in person, but were nevertheless excited by the opportunity, and the prospect that if Threatin took off, it could become a regular, paying gig.

The quartet started practising in Hesperia every other weekend from July until October, then the Eameses put them up in the guest bedrooms and on their living room sofa for a full week before departure. The band practised non-stop until it was time to leave for the airport in Los Angeles.

“It was exciting, it was cool,” recalled Carney, a 24-year-old car mechanic, who hadn’t travelled much outside of California before. “My first tour ever, we’re going to Europe and the UK - that’s pretty crazy.”

At the time, the only thing that struck any of the three hired band members as odd was a surprise announcement that their promised $300 fee was now actually their food budget. Davis says he was upset, knowing that $300 would hardly last a week in an expensive city like London. (Eames disputed this account, saying the band members always knew the money was for per diem.)

“But I’m the kind of person where I’ve given my word that I’m going on this tour, and my word means something to me,” he said. “I didn’t want it to end up screwing over the band.”

After two days of London sightseeing in the hired Mercedes-Benz Sprinter van driven by Kelsey, the band arrived for the first show of the tour at The Underworld in Camden. While the band was backstage taking giddy pre-show selfies, Jon Vyner, The Underworld’s booking manager, was expecting a fairly sizeable crowd for a Thursday night.

The gig had been arranged a month earlier by Threatin’s booking agent, Casey Marshall, from an LA-based company called StageRight Bookings. Marshall had paid the venue’s £780 ($979) hire fee and informed Vyner via email that they’d pre-sold 291 tickets for the evening. That would have packed the venue to well over half its capacity, and Vyner had staffed the doors and bar accordingly.

“We would have been overjoyed if that many people actually turned up,” he said.

Marshall had also arranged for two support bands to play, and when Prunera and Davis slipped into the audience to check them out, both noticed there were only a handful of spectators.

“I kind of thought to myself: ‘Maybe this is a band that’s not really that popular and they’re kind of just starting out,’” recalled Davis.

But by the time Threatin took to the stage for their first real performance together, the audience had actually dwindled further. Prunera, who’d simply assumed that Threatin’s fan base in the UK must be massive, was disappointed, but tried to put it out of his mind.

“I thought: ‘Who knows, it’s a Thursday night, maybe nobody’s out, people gotta work tomorrow,’” he said. “We weren’t stressing out because these things can happen.”

Behind the scenes, however, Vyner was “quite angry”.

“I told Casey by email never to contact us again,” he said.

Oblivious to the trouble brewing, the band moved on to the next stop at Trillians in Newcastle upon Tyne. Marshall had hired Rob Moore’s Dogsflesh as the opener. As a seasoned musician touring since 1982, Moore took the time to check Threatin out before accepting the show offer, and was pleased with what he saw.

“Loads and loads of hits and views and likes and comments. We thought: ‘Yeah, this guy’s obviously the real thing,’” he said. “We thought if we can get on with their booking agent in America, maybe they can open up a few more doors for us.”

Once again, however, as the support band came on, the venue was nearly empty. After Threatin failed to acknowledge the members of Dogsflesh after their set - a backstage faux pas - Moore decided to pack up and leave without staying to watch the headliner. As he walked out, Moore says he saw five people in the audience, two of whom were members of his own band.

Things finally boiled over at the band’s fourth gig, The Exchange in Bristol, where Marshall had told the venue to expect 180 pre-sold ticket holders.

Billy Jon Bingham, frontman for the band Ghost of Machines, says his band took the Bristol gig unpaid as an opportunity for more exposure and a chance to sell merchandise. But he arrived to see that there was no queue and the Hollywood promoter was nowhere to be found. Ten minutes before they were due to take the stage, a manager at The Exchange waved him over.

“He pulled me aside and said: ‘They haven’t sold any tickets. I’ve asked him to cough up the money that we’ve lost or we’re losing on the bar, otherwise they’re gonna close the venue,’” he recalled.

Bingham says he saw Eames, who up until this point had been slinking around the venue with his hood up, go to a cash point and withdraw the £400 needed for the show to go on. Bartender Jonathan Minto, who had come in to help handle the expected crowd, overheard his manager quibbling with Eames over the additional cost. But Minto said that at the time he believed they’d all been “taken for a ride by a shady promoter”.

That evening, Threatin took the stage to an audience of absolutely no-one.

“My initial reaction was to feel sorry for him and the band, because having no-one turn up at your show is pretty demoralising,” wrote Minto in a message to the BBC. “But then… during his set, we started the internet sleuthing.”

Minto said that when he and the other idle bartenders watched the clip that appeared to show Threatin playing to a sold-out crowd in an arena somewhere, they saw that Eames never appeared in the same shot as the throngs of fans in the pit.

“He had literally just spliced footage of a crowd of at least 20,000 people rocking out at a real gig with close-up footage of Jered playing in front of wall,” said Minto.

The next morning, he posted a long Facebook message, laying out everything he’d found out the previous night, thinking his friends in the music industry would get a kick out of it.

“Threaten [sic] is essentially a fake band. 38,000 likes on Facebook which have ALL been paid for,” he wrote. “The 100 or so people attending the event page (and all the other event pages for their tour) are all based in Brazil. Every comment on their youtube videos is phoney.”

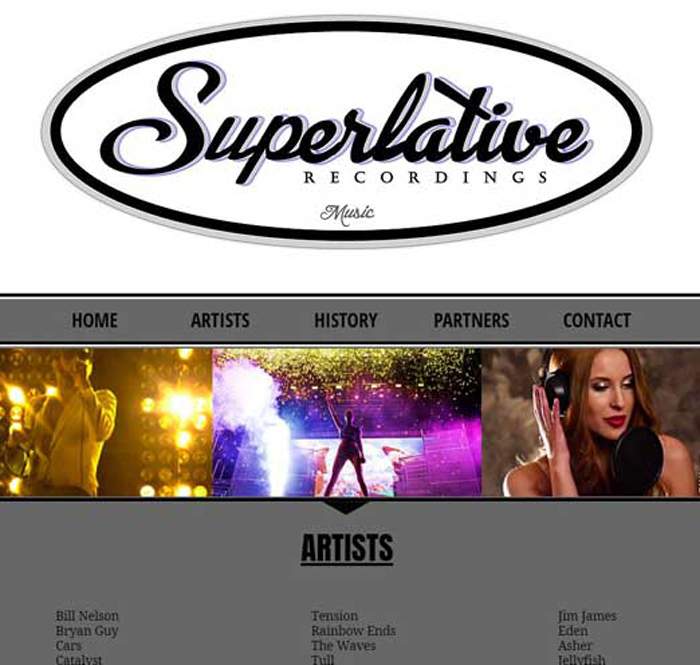

The post began to spread. After reading it, Tim Williams, editor-in-chief of the blog Sick Chirpse in London, went on the websites of the companies that allegedly represented Threatin: Aligned Artist Management, StageRight Bookings, Magnified Media PR and his label, Superlative Music Recordings.

“It looked like it was made by a kid in 10 minutes,” said Williams of the websites. “It was very suspicious.”

When Williams googled the other bands allegedly signed with Superlative, nothing came up. All four websites were registered to the same anonymous GoDaddy account.

On 9 November - a little over a week into the tour - Sick Chirpse, MetalSucks and NME all posted the first articles exposing what Williams called “the bizarre story of Jered Threatin”. Minto said he and other workers at The Exchange had also been contacting the venues further along the tour route to warn them not to believe anything that Threatin’s management was telling them. He says his phone began going crazy with notifications.

“People were really digging into who he was and finding out crazy information nearly every minute,” he said.

A mountain of damning evidence began piling up.

The news outlet that had awarded Threatin “Rock Artist of the Year” in 2017? Fake.

The profile photo of Lisa Golding from her Facebook page? Lifted from a Montreal photographer’s website.

The physical address for StageRight Bookings in Los Angeles actually belonged to a suicide prevention charity.

By the time the band arrived for its fifth gig in Birmingham, Carney could tell something was up.

“It just didn’t feel like we were welcome,” he said.

Cracks began to form within the band as soon as they disembarked from the ferry in Northern Ireland. Davis switched his mobile phone back on to find that his inbox was full of emails from concerned friends as well as derisive internet trolls, haranguing him for his role in the “fake band”. As he read the story in NME, Davis became alarmed that he “had no idea who Jered is, or what he’s capable of”.

While Kelsey and Jered were checking in to the home they had rented for the band, Davis showed Prunera and Carney one of the links that had been sent to him.

“At that point I just told them: ‘Let’s keep quiet and just try to find out as much as possible and get a game plan together,’” he said. “From then on we communicated through text.”

An awkward scene unfolded that evening in the living room, with all three hired bandmates furiously texting back and forth to one another, while trying to play it cool with Jered and Kelsey sitting just feet away.

“I get online and sure enough, it’s everywhere. It’s all over the internet,” said Prunera. “I’m like: ‘What is going on?’”

Davis’ mother had flown from Las Vegas to Belfast to see her son play, but instead, he conscripted her to help the band gather their luggage and flee the rented house without a confrontation with Jered. But before that could happen, Jered came downstairs and asked if anyone else had been getting any weird emails.

“Jered seemed like he was just as confused,’” recalled Prunera. “He said he was a victim. We said: ‘Dude this is over.’”

Davis left that night with his family. Prunera followed the next morning, checking into a hotel and ultimately relying on an aunt to fund his trip back home. Only Carney, who felt unsure about what he was reading versus what Jered was saying, agreed to stay.

But without a drummer or the other guitarist, the Breaking the World tour officially broke down.

By then, the story had gone fully viral. MetalSucks filed a dozen follow-up stories, breathlessly chronicling the band’s every blunder. Threatin became the talk of music podcasts and YouTube channels. The New York Times called it “a most puzzling hoax even for 2018”.

When journalists discovered that Jered Threatin’s real name was Jered Eames, it didn’t take long to track down his older brother, Scott, to their hometown of Moberly, Missouri. He seemed unsurprised by his younger brother’s antics.

“I caught an article pretty early on, and once I saw the picture on there I kind of rolled my eyes,” he said. “I was hoping it would blow over.”

Scott, who plays guitar for the extreme metal band NEVALRA and under the stage name Wicked One for the black metal band Thy Antichrist, said he hasn’t spoken to his brother in about six years - since Jered and Kelsey packed up and abruptly moved to California in 2012.

According to Scott, the rift began over the extreme metal group, Saetith, Scott and Jered formed together, an outfit that in Scott’s estimation had real promise and had started building a reputation. They even travelled to Puerto Rico together on a 2011 tour.

But things soured when Scott went online and saw that Jered had changed the band’s Facebook page to show that he - not Scott - had played guitar on their upcoming recordings.

“He was my best friend, honestly. I was pretty isolated,” says Scott. “Almost overnight it went from best friend to not speaking.”

He says he still hopes that someday his wayward sibling will come home, for their parents’ sake.

“He’s still my brother,” he said.

Back in Europe, Carney went sightseeing with the Eames. They toured an Irish castle, and visited the Eiffel Tower in Paris. Carney says it was fun. The epic disintegration of the tour was discussed only shallowly, and Carney did not confront Jered.

But the final straw came when Jered released what was up until this point his first and only statement on the debacle. It was just three sentences long:

“What is Fake News? I turned an empty room into an international headline. If you are reading this, you are part of the illusion.”

The internet collectively groaned. But for Carney’s mother, it was a sign that the whole thing had gone too far - she insisted Carney let her fly him back home to Los Angeles. He acquiesced.

But Carney seemed to be the last person still willing to believe that Threatin’s management existed, or that the whole tour hadn’t simply fallen victim to an unscrupulous promoter. Not long after returning, he even posted a video of himself covering his “favourite” Threatin songs on YouTube.

“There’s still a lot of questions. I don’t really want to come to any conclusions until I know,” he told me at the time.

“I want to hear what he has to say.”

By the time I’d heard about the saga, Eames seemed to be in the defensive crouch familiar to anyone who’s watched a viral internet-shaming unfold - his Twitter and Instagram accounts had been made private. A series of YouTube interviews with him (which turned out to be Eames interviewing himself) had disappeared from the web. Yet at the same time, his critics were finding themselves blocked from his Facebook page, a sign that from somewhere on the cancelled tour route, the wounded frontman was watching.

During this time, he was also ignoring all requests for interviews from journalists. I sent him a direct message on Twitter anyway, not expecting to hear back. He responded within hours.

“I'll be back in LA next week.”

About two weeks after he’d returned home, Jered Eames sat at his dining room table drinking a Coke and scrolling through the reams of vitriol that come up when you plug “Threatin” into Facebook’s search bar.

Kelsey sat beside him as one of their four cats swished around the couple’s feet.

“Threatin is a total fraud,” Jered read aloud, a slight Missouri twang still discernible in his voice. “We stupidly hired our venue out to his agent Casey Marshall based in America - I assume Casey is Threatin’s mother.”

He read further silently.

“They think my parents paid for the whole thing, that’s hilarious,” he said.

Jered moved out of his parents’ house and into a house with Kelsey when the two were still in high school. He claims the tour was funded with the money they squirrelled away when he was flipping burgers at a Moberly Burger King and installing court-mandated breathalyser devices in people’s cars.

Neither of them is in touch with their families back in the Midwest.

“I’m very much a loner,” said Jered. “Not only do I not want friends, I don’t want family either.”

He admits that friction within his family did precipitate his cutting off contact with Scott and his parents, but he says that what really sent him to California was a sudden, violent coughing fit that landed him bent over the sink, choking out blood. Without going to a doctor, he said, he simply assumed he was dying and decided to make some dramatic decisions.

“I just went: ‘Am I really happy doing what I’m doing with my life?’ And I went: ‘No, I’m not. I’m gonna move to Los Angeles.’ Everything I thought about doing, I’m doing right now.”

The Eames live a very small life together. They say they do not socialise with anyone but each other. They rarely go out, and when they do, it’s to drive around and talk. The fact that the single motivating factor in Jered’s life is an insatiable need for fame, yet he has no friends, is a paradox he acknowledges, but has no explanation for.

Tapping away on his laptop, Jered tried - and repeatedly failed - to log in to one of the hundreds of fake Facebook profiles he’d started over the past year, since the launch of the album he’d written and recorded, playing all the instruments himself, in the huge studio space on the east side of the house. Although he made a few unsuccessful attempts to promote Breaking the World through traditional means, he quickly decided to go a different route.

“Why do I need some gatekeeper to tell me that it’s what they want it to be, or it’s good enough for them?” he remembered thinking. “I’m going to find my own way to do things.”

Earlier in our meeting, he’d reached under his bed and fished out five notebooks. He flipped one open on a random page and showed me that line after line was filled in with email addresses, their passwords, and a little lock symbol to denote that they’d been locked down or flagged as spam, and were now defunct. In the early days, these accounts had been used in the comment sections of YouTube and on Facebook to sing Threatin’s praises.

He kept the names of his fake Facebook accounts in an app on his phone as well: Mark Jaime. Sarina Goodman. Laura Wales. Ann Corbi. Casey Johnston. Jessica Rice. Josephine Gossan. James Grundy. Alicia Tanlor.

Jered had also gone through the house pulling burner phones out of various drawers, all of which he said were used as a means to create the fake accounts, which require a unique phone number.

“There should be more,” Kelsey had muttered as she looked down at a pile of eight phones.

In my conversation with the couple, they quickly admitted the hoax. Indeed, all the likes and the views and the comments were paid for, made by bots or Jered himself. Casey Marshall, Joe Abrams, and Lisa Golding were also all Jered (Kelsey had provided Golding’s voice over the phone).

None of the companies tied to Threatin really existed. He created the label first, to release his debut album online in August of 2017, and the universe of phoney companies and contacts had expanded from there.

When he tried to generate press, he invented a publicist. When he needed to book some gigs, he created a booking agent. He viewed the entire ecosystem of the music industry - the managers, booking agents, promoters, even photographers and videographers - as just a series of roles he can fill himself.

“If a band approaches a venue and says: ‘Hey, we wanna play this venue,’ you’re going to get ignored,” he says. “All it has to do is look like it’s coming from a booking agency - doesn’t even matter what booking agency, even a fake one - and then you’ll get talked to and you can get things booked. Simple as that.”

As he explained his tactics, Jered was relaxed, confident - not the slightest bit embarrassed. But that’s because he had something he was eager to show me - a series of emails that he said he sent out under yet another alias, a Gmail account belonging to “E. Evieknowsit”.

“URGENT: News tip,” the subject line read.

“The musician going by the name Threatin is a total fake. He faked a record label, booking agent, facebook likes, and an online fanbase to book a European tour. ZERO people are coming to the shows and it is clear that his entire operation is fake,” he wrote, including links to all his phoney websites.

“Please don’t let this man fake his way to fame... Please Expose him.”

The first such message he showed me was dated 2 November, a day into the Breaking the World Tour, and a week before the first news reports were published. He says he sent the messages out to a database of reporters’ emails he keeps in a massive Excel spreadsheet on his laptop - to outlets like the Huffington Post, Spin, Consequence of Sound, Rolling Stone, The Guardian, Pitchfork, New York Times, MetalSucks and, yes, the BBC. Although it was unclear if the tips directly resulted in coverage, some of the emails appear to have predated articles.

During the tour, when the bandmates weren’t looking or in another room, Eames claimed he was on his phone on Facebook under his various aliases, stoking the controversy.

If he is to be believed, the public shaming of Jered Threatin was nothing but a carefully orchestrated publicity stunt. He’d even had Kelsey at the ready with a video camera, in the hope that someone at one of the venues might try to fight him and create a viral video to boot.

“I manufactured my own destruction,” he said proudly. “My idea was, how am I going to fill these empty rooms? I’m going to fill them with eyes from the digital world. That was the objective from the beginning.”

Were the things I’d taken as signs of humiliation - the closing of his social media accounts, the disappearance of the obviously fake YouTube interviews - actually Jered herding eyeballs towards his music, which he left up? As of writing, Threatin’s single Living is Dying has been viewed more than 1.2 million times.

Ignoring interview requests was another form of stoking the fire.

“As soon as the questions are answered, the story’s less interesting,” he said.

Which brought us to the awkward fact of my sitting in his house, listening to his explanation.

Maybe by writing the very story you are now reading, I’ve played a part in carrying out Jered Threatin’s master plan.

Jered claims to be in meetings day after day with movie producers looking to fictionalise the saga, bookers who want him out on the road to capitalise on his notoriety, and music producers and labels who want to talk about his next album.

Kelsey has hours of footage, from the auditions at SIR Studios all the way through the tour, which they intend to use in a documentary. She even taped him sending out news tips about his own fraudulence from their hotel in Newcastle.

“There is no villain character anymore in rock music, or really in all music,” he says smugly. “I’m trying to vilify myself.”

When I press him to find out if he feels bad about deceiving anyone - especially his former bandmates - he is unrepentant, and claims he offered to pay for them to fly home after the tour fell apart.

“The job is the same either way, and the only difference is the number of people standing in front of you,” he said. “When they [the band] are saying: ‘I want to be a touring musician, I want to be famous and I want this and that’ - that’s what [they] got.”

Although Eames provided emails, receipts, videos and other documentation to back up his story, ultimately it is still possible that the tale he laid out is not true. Perhaps the “E. Evieknowsit” messages were backdated. He didn’t allow me to take photos of the inside of his notebooks, because some of those accounts are still active, roving the internet, and a part of what he said are forthcoming publicity stunts.

For his part, brother Scott was utterly unconvinced when I relayed Jered’s version of events.

“He’s a master manipulator,” said Scott. “I want to be the voice of reason here. This is like every other profession and you’ve lied to everyone in your profession, so I don’t know where he’s going with this. He can be the internet sensation if he wants, but he’s not going be the musician that he wants to be.”

In our last conversation, however, Jered dismissed the idea instantly that the music might not be good enough to carry him forward.

“I came home to literally thousands and thousands of CD sales. I have a cult following,” he said.

His only regret, he said, is that he didn’t show up to one of the cancelled shows, where his internet infamy would have generated a proper audience - perhaps the final stop in Italy. He would have liked to have gone on stage, faced the crowd, and refused to play a note.

“I just would have gotten booed off stage, or bottled, and it would have been a beautiful piece of stage art,” he said wistfully. “It’s like, I show up and I play for no-one. And then when there’s an audience, I don’t play for anyone.”

When I left the Eames’ home, I drove back to my hotel, where I was meeting the last person on earth who seemed to still believe in Threatin - former bassist Gavin Carney. He’d driven up with his father to answer my questions from another town outside LA. He had worn a suit and a floral print tie for the occasion, and seemed especially young in the moment, standing in the hotel lobby next to his father.

I told him that only a short while ago, Jered had confirmed that the whole debacle - including the fake management companies and labels, the empty venues, the crush of media attention - had all been orchestrated. Sitting on a couch in the hotel suite, he looked crushed.

“Wow,” he said. “It’s crazy. It’s amazing, if that’s the case, the amount of lies he was able to keep track of and be able to consistently repeat. It’s... it’s very shocking.”

I repeated what Jered had said to me - that neither he, nor Prunera nor Davis would have got as famous if Threatin hadn’t turned into a three-ring circus. Carney agreed that in his case, Jered was essentially right.

“I’ve been approached. I don’t mean to name drop, but, by a lot of people who are sort of high up,” he said. “I did get on the news. I’m here talking to you right now.”

He thought for a moment.

“Personally I wouldn’t want to do anything like that. I prefer to be kind of a goody two-shoes,” he said. “I put videos up, I try to put myself out there as honestly as I can and hopefully find somebody who wants to work with me. That’s the way I prefer to do it.”

Of the three band members, Carney was the only one that Jered said he would like to play with again. But he acknowledged that Carney would probably never agree to it. In our entire conversation, it was the only time I thought Eames sounded unsure of himself.

When I asked Carney if he could ever be friends with Jered, he said he didn’t know.

“It’s hard for me to say now. It’s hard to know what is true and what isn’t.”

Update: 19 December 2018

“The publicity stunt for this is done,” Jered Eames assured me at the end of our interview. “Anything I’ve said to you is factual.”

To prove that he was indeed the one that tipped off the media to the hoax Eames forwarded me 16 different news tips sent from the “E. Evieknowsit” account. Four of them were sent to two different general BBC news tip email addresses, and the earliest of those was dated 4 November - five days before the first stories broke.

My colleagues looked for the emails, but because those inboxes are routinely purged, they had nothing.

After we first published our story, I began reaching out to reporters at the other outlets who had allegedly been sent emails. The earliest one was reportedly sent on 2 November to the “tips” inbox for the entertainment magazine Variety.

“Yes, we got this email,” a helpful Variety reporter wrote back, attaching a copy with the exact same text that Jered had shared with me.

Then I looked closer. The timestamp on Jered’s copy said it was sent on “Fri, Nov 2, 2018 at 12:16 PM”. The copy from the Variety reporter read, “Sat, Nov 17, 2018 at 4:32 PM”.

An editor at MetalSucks, which did some of the earliest breaking stories on Threatin, could not find an alleged 7 November email that Jered shared with me. Instead, he found a different email from Evie in their inbox, pointing him to a YouTube clip from one of Threatin’s empty shows. It was dated 17 November.

As I went down the line, I found that the New York Times, Ultimate Classic Rock and Metal Insider all got the “E. Evieknowsit” email on 17 November. But by this date, these outlets had already extensively covered the Threatin story.

Finally, the BBC’s IT specialists managed to recover two deleted messages from “E. Evieknowsit”.

Both were sent on 17 November, less than an hour apart.

When I texted Jered to tell him what I’d found, he said he would respond.

He never did.