In fear for her life, Kurt’s Jewish single mother fled Nazi Vienna for the UK in 1939, leaving him behind. This 14-year-old’s story of abandonment and adversity can be told for the first time, through recently discovered letters.

It is mid-March 1939 and 14-year-old Kurt and his devoted Jewish single mother Hedwig are standing on the platform of a railway station in Nazi Vienna saying their tearful goodbyes.

The destination of the impending journey is the UK, and the purpose is to escape the intensifying persecution of Austria’s Jewish citizens.

Since December 1938, trains have been carrying Jewish children from Germany and German-annexed Europe to safety in the UK, thanks to the Kindertransport operation, a charity-run scheme sanctioned by the British Government.

Many children have already fled Austria, leaving selfless parents behind to face an uncertain fate - in most cases, a barbaric death.

Hedwig and Kurt, her only child, wave to each other one final time as the train steams away from the station. Then, pulling himself together, Kurt turns around and walks back into a hostile city. He will not be joining the children on the Kindertransport today.

Instead, it is Hedwig who boards a regular train to safety.

This is the starting point for a dramatic story told through letters from Kurt to Hedwig after she arrived in Market Harborough, a town in the East Midlands. Here she would be working as a household cook, after obtaining a domestic service visa of the type issued to 20,000 Jewish Austrian and German women intent on escaping the Nazis.

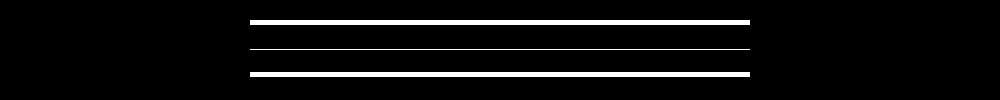

Hedwig’s passport in 1939: Note the J for Jew

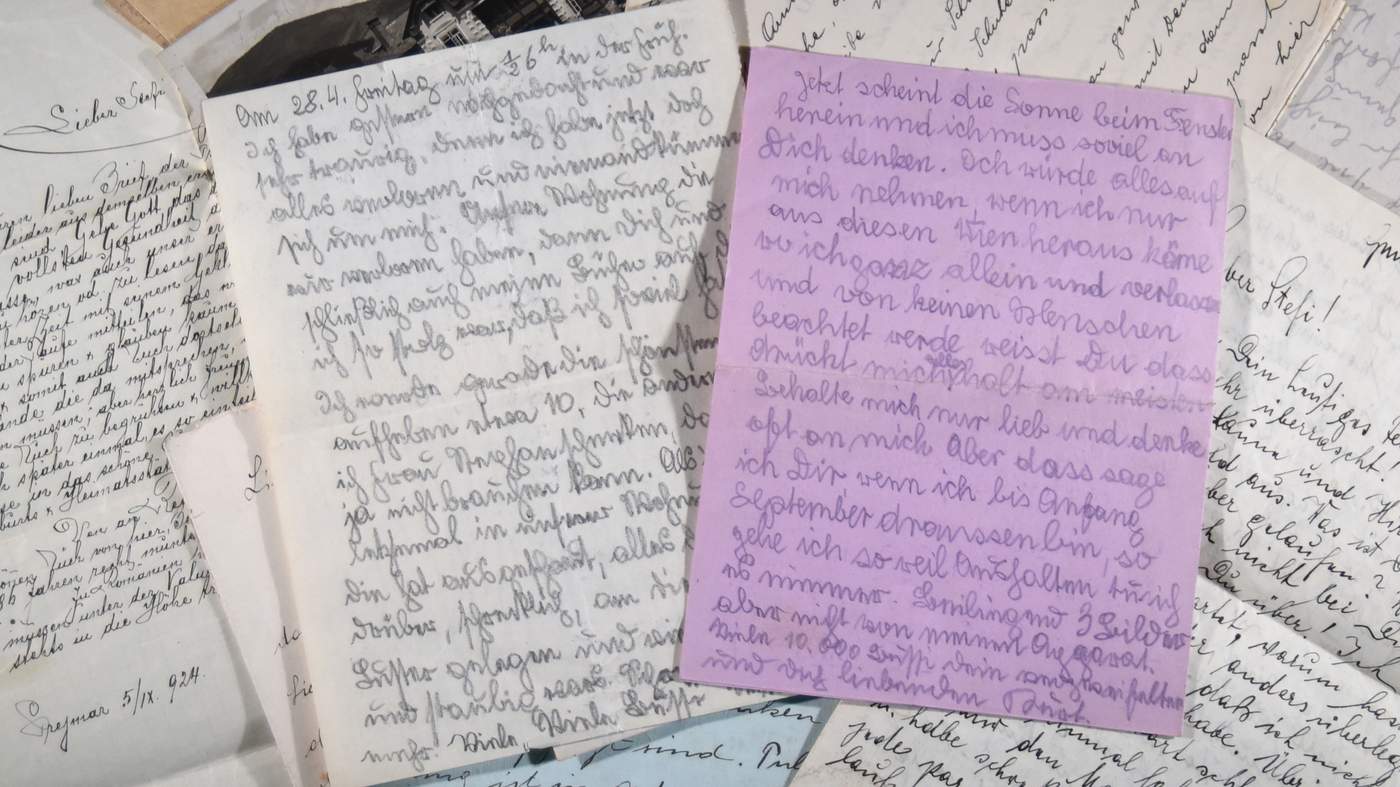

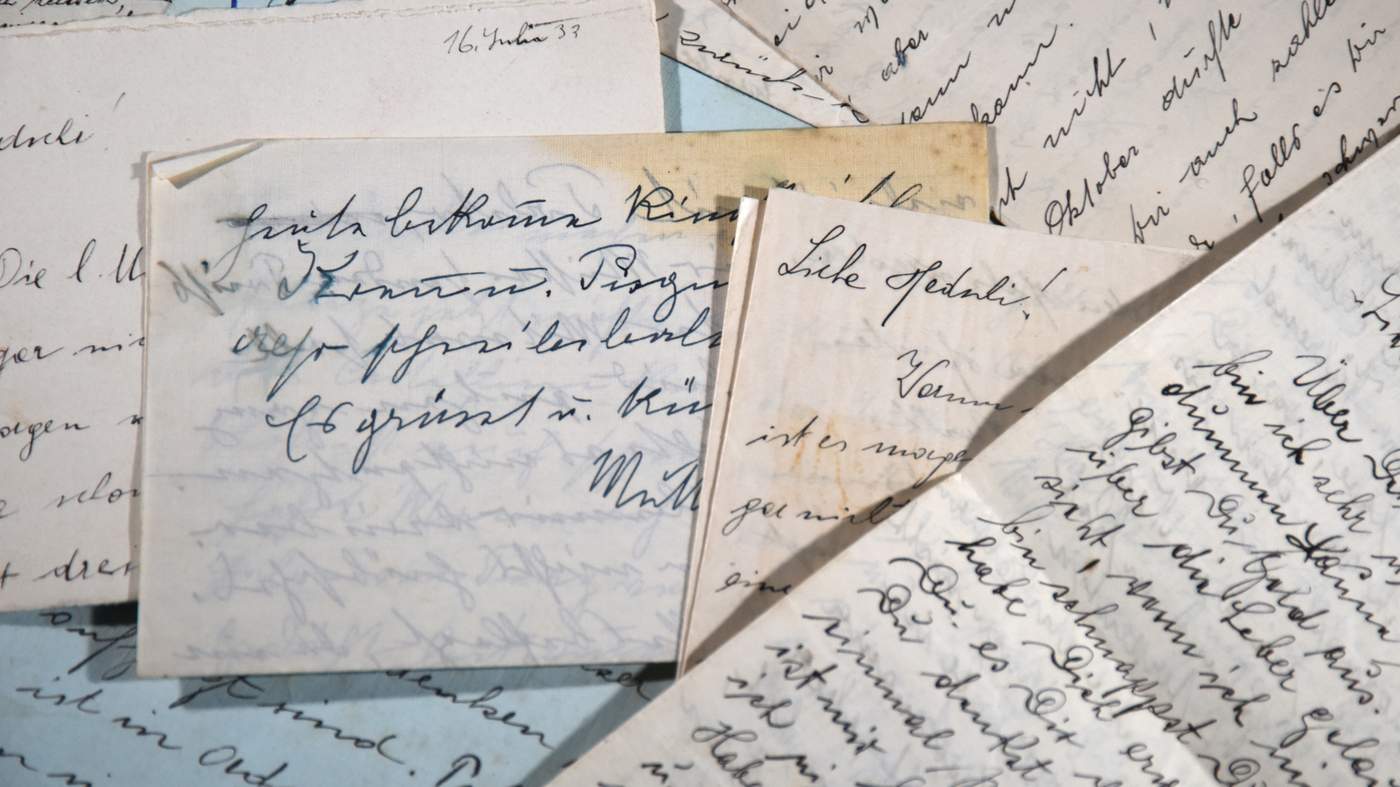

The 40 letters, discovered in a loft in the UK earlier this year, have now been turned into an online exhibition by the Wiener Library Holocaust archive in London for what they add to our knowledge about the experience of pre-war refugees.

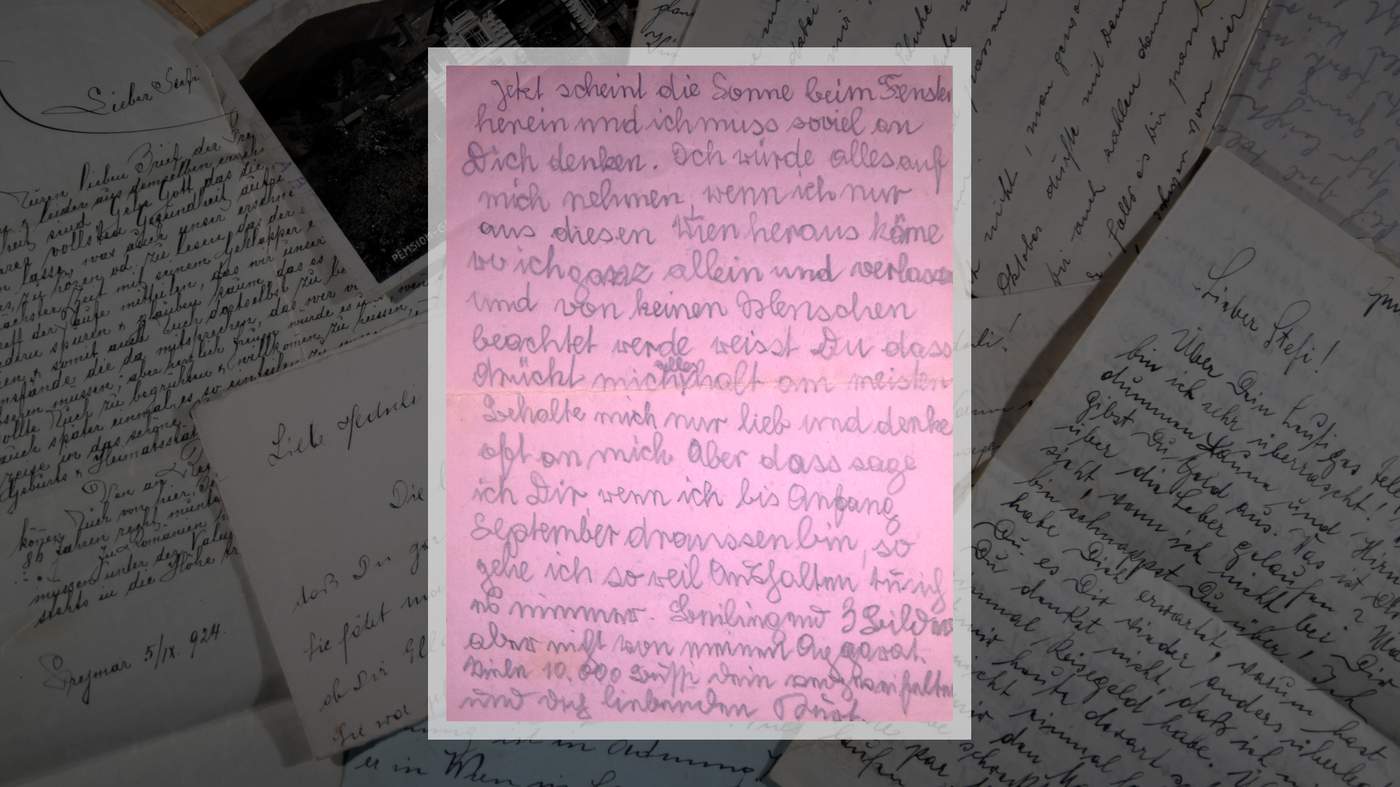

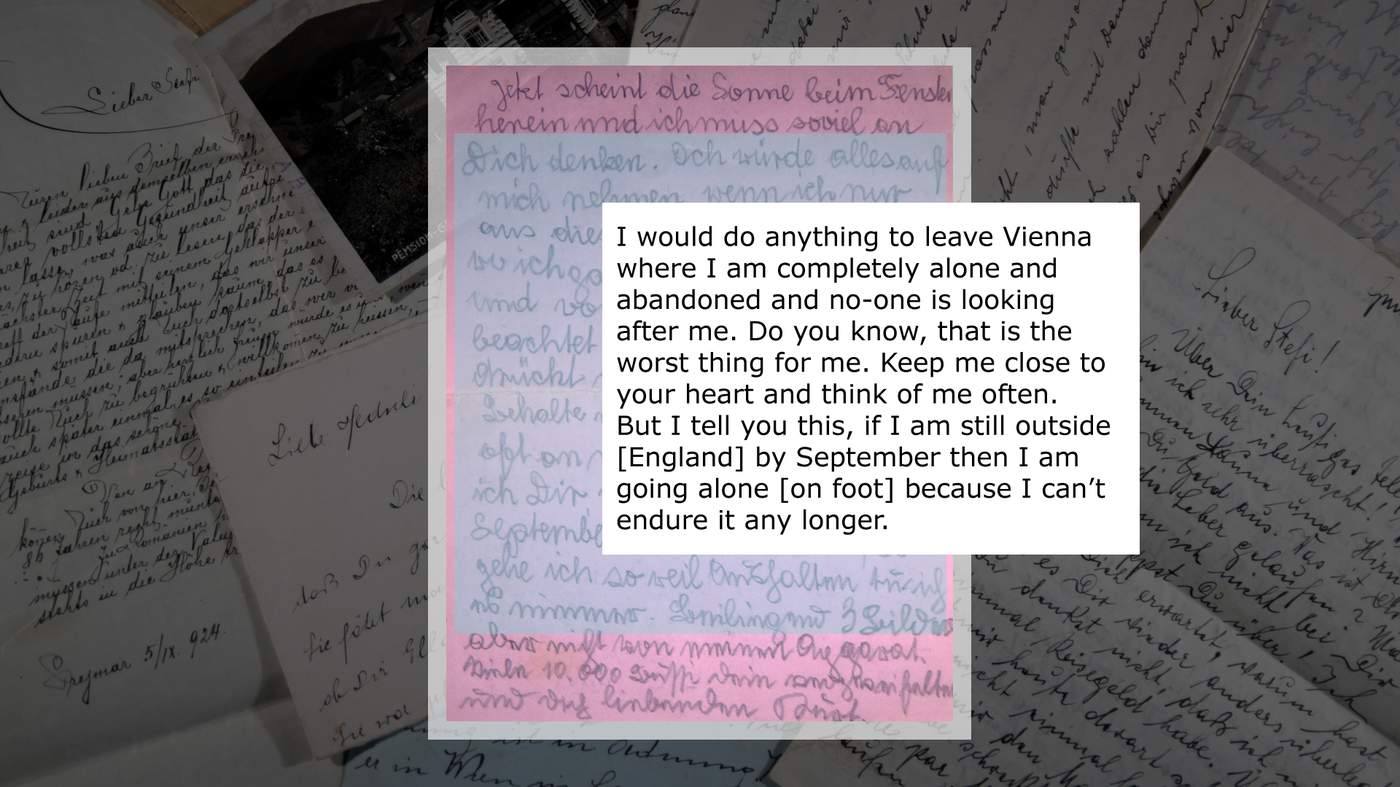

The letters reveal that there was no prospect of a reunion between Kurt and Hedwig at the time of her departure. They trace Kurt’s loneliness, his increasing destitution and the harassment he faced because of his Jewish background. They also reveal how long he endured such conditions and the narrowness of his eventual escape.

All of these were unexpected discoveries for me, Kurt’s son.

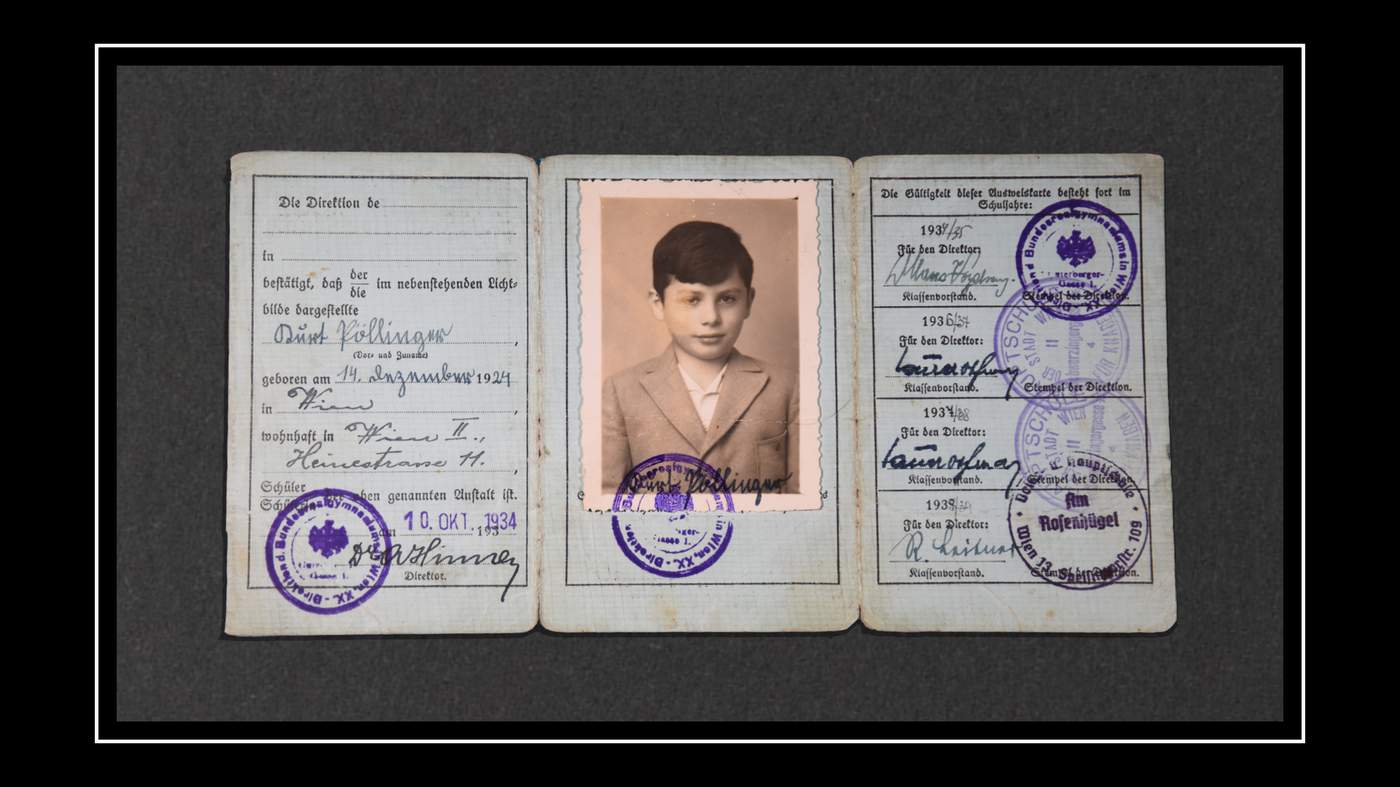

Otto Kurt Pöllinger was born in Vienna in 1924 and lived in the centre of what was known as Vienna’s Jewish district, Leopoldstadt.

His most cherished memories were of the frequent visits to his mother’s small home town of Gmünd, where her brothers were respected third-generation shopkeepers. It was around here, deep in Austria’s forested Waldviertel area, that he developed his love of the great outdoors and activities such as swimming and mushroom picking.

Kurt’s life was unsettled in 1936 when his Catholic father Stefan and Jewish mother separated. They legally divorced in 1938. Stefan, who was said to have been unkind - although I didn’t discover the full extent of that until I found the letters - moved out of the family home.

But the most testing times of Kurt’s childhood were yet to come.

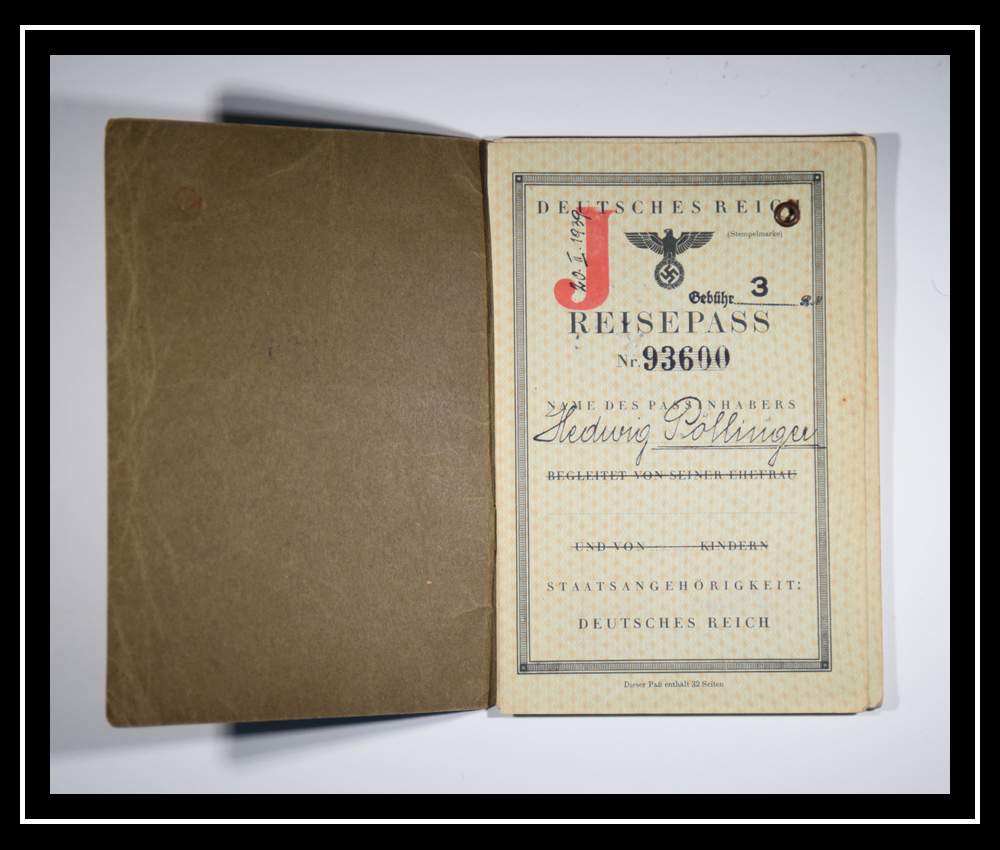

Hedwig and Kurt, in ‘Lederhosen’, outside the family shop in Gmünd, 1930

In March 1938, Nazi Germany annexed a none-too reluctant Austria, an event known as the Anschluss. This marked the first major territorial expansion for Germany in the run-up to World War Two.

Life changed immediately for Austria’s Jewish inhabitants, who formed a greater proportion of the total population than in Germany. Most of Austria’s Jews lived in Vienna, a thriving hub of Jewish life in central Europe.

They became subject to the hundreds of regulations and decrees already affecting those in Germany and which continued to grow. The legislation radically limited where they could work or study, what they could own, who they could marry and even where they could live and go.

The aim was to deprive Jewish people of their rights, to the point that they did not qualify as citizens.

Kurt personally witnessed the effect of such persecution.

The family’s shop in Gmünd was swiftly expropriated and his uncles were forced to leave town for Vienna. He later described to me watching Jewish people in Vienna being humiliated by being forced to perform tasks such as scrubbing the streets.

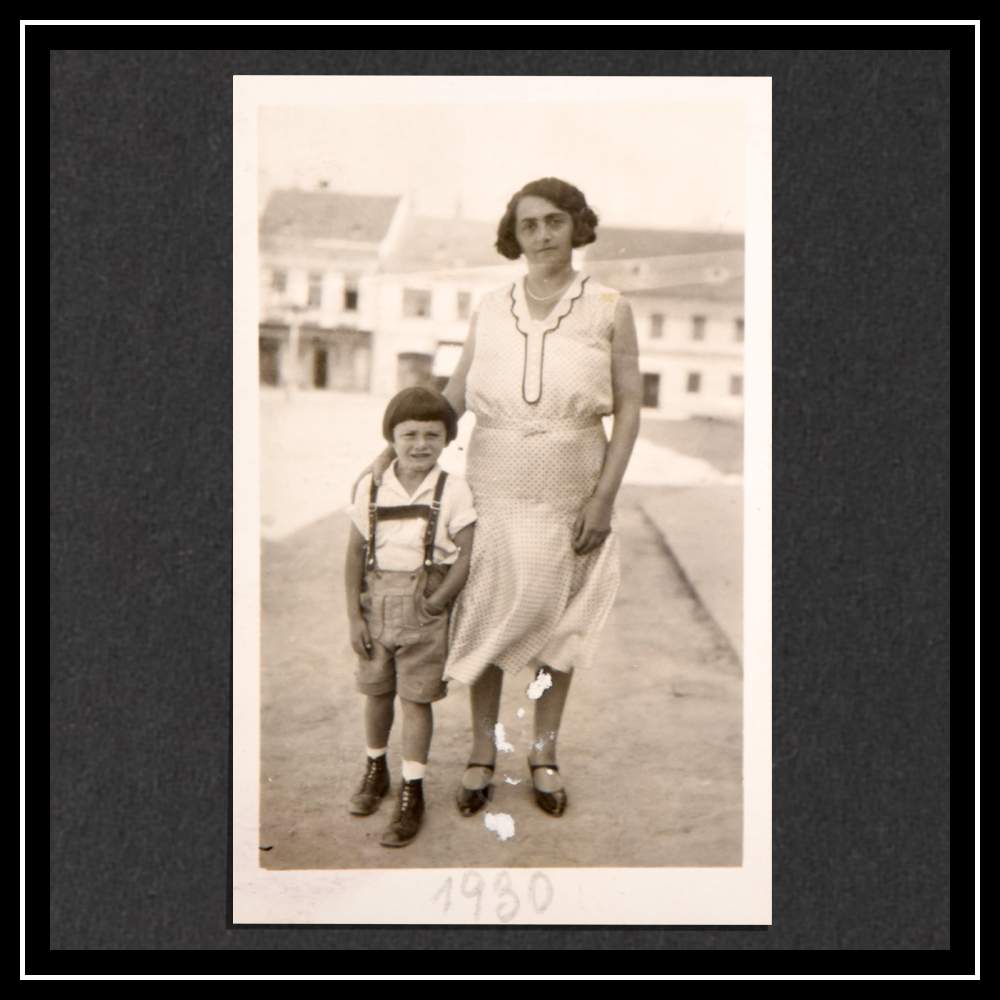

Many synagogues and Jewish shops were destroyed in his neighbourhood on Kristallnacht (or Night of the Broken Glass) in November 1938.

A smashed Jewish shop window in Berlin (Getty)

This period of violence, orchestrated by the Nazi authorities, also marked an uptick in the arbitrary arrests of Jews. More than 6,000 were incarcerated in Vienna, some probably in Kurt’s old school, which had been converted into a prison by the Gestapo, the feared secret police. Many inmates were sent from there to concentration camps.

Around 60,000 of Austria’s Jews would be deported and murdered by the end of WW2 in 1945. The rest, a lucky but scarred 120,000 or so, managed to escape the country before the war started in September 1939.

Hedwig would be among those, and the first in her immediate family to make it out. But this is where the record went quiet because neither Hedwig nor Kurt spoke much about their experiences from that time.

Following their deaths in 1967 and 1990 respectively, I had resigned myself to the fact that the circumstances of their escapes to the UK would remain a mystery.

But it turns out that Hedwig had kept a detailed record of this terrible time in the form of letters that, until earlier this year, only she and Kurt had known to exist.

One evening in January 2018, I was in my mother’s new house looking through removals boxes for Hedwig’s old photo album and documents. I wanted to help an Austrian historian Dr Friedrich Polleross, who had once interviewed surviving family members for a book. He needed photography to illustrate his new book that focused on the vanished Jewish families of the Waldviertel.

When I eventually found the album, the photos I remembered were all there - of Hedwig as a baby, posing in her finery with young friends in Gmünd, standing beside her husband with baby on knee, and eventually portraits of her alone with Kurti, as he was known affectionately.

Then beneath where the album had lain, the lid of a battered 1940s-style white and gold chocolate box that I had never seen before caught my eye.

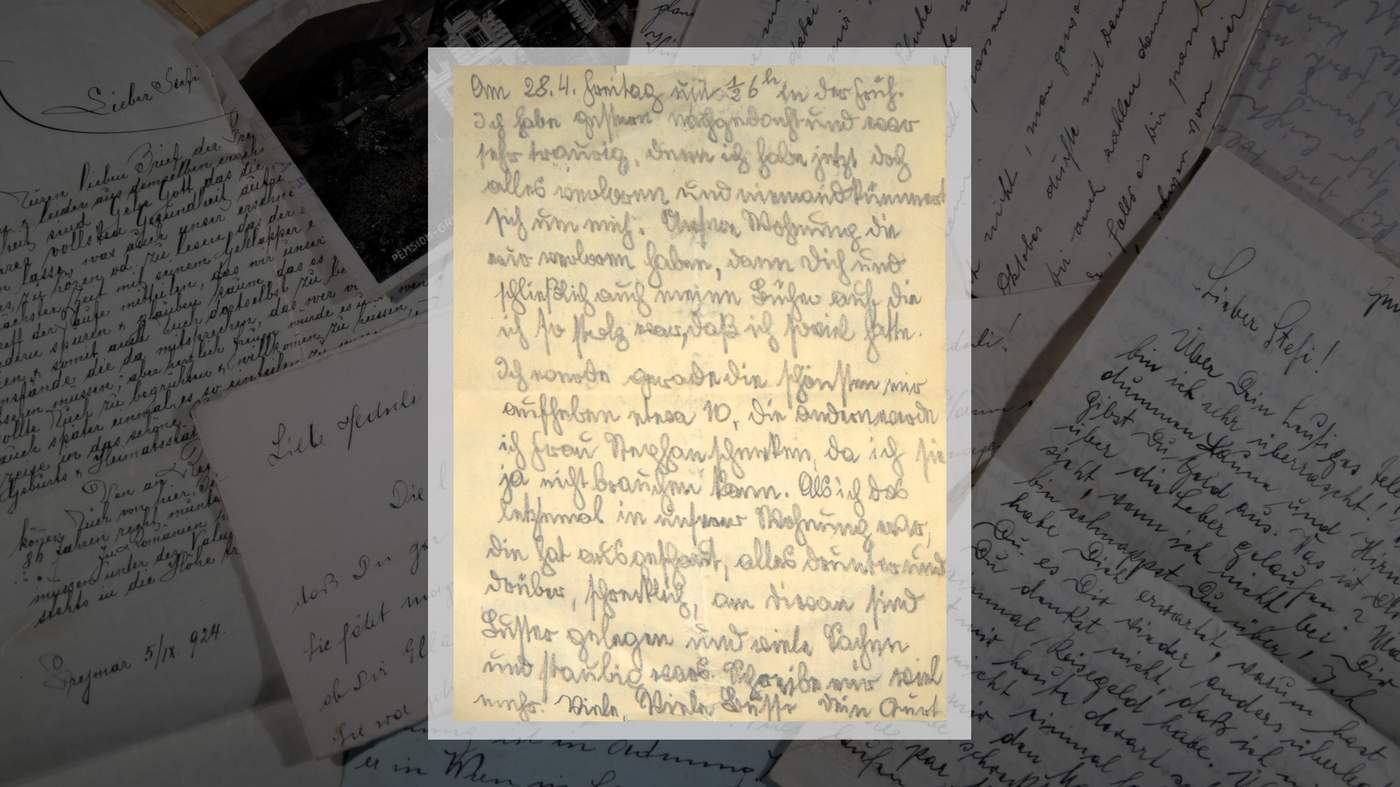

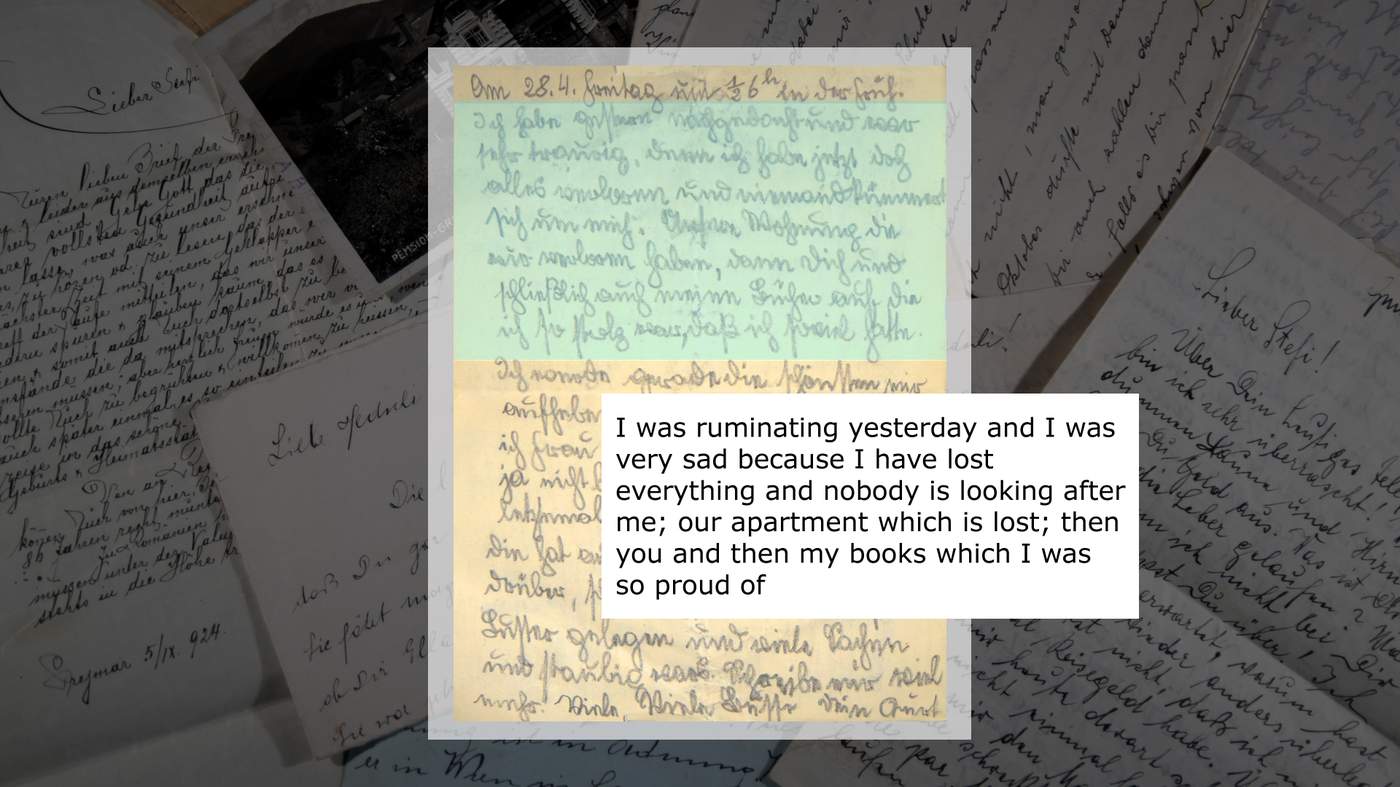

I lifted the lid carefully to find 200 yellowing letters written in unfamiliar and impenetrable handwriting, packed inside haphazardly. Sifting through the letters that were mostly addressed to Hedwig and from the 1920s to 1940s, I could make out that many were signed Kurti and were dated between March and July 1939.

As the letter transcripts arrived in order, I started to appreciate that Hedwig must have weighed certain factors when deciding whether to leave, and her decision was not as cold-hearted as it first appeared.

There were some safeguards in place for Kurt. He was at school for most of the week, and his mother’s relatives were still in the picture.

Despite this, he expressed his sadness early and often: “No-one is looking after me…I am so lonely,” he writes on 22 March. But later letters reveal that the teenager was able to spend some time not dwelling on his predicament. With his inquisitive mother clearly pressing him for details about his daily life, he writes: “I went walking with Eva (not my type, too homely),” on 16 April.

But the safeguards were not going to last, with dire consequences as the next batch of letters would reveal.

Kurt's father Stefan

Kurt hated his school and not just because of the slop he complained of being served at mealtimes. He had to hide his origins and his mother’s location from his classmates and the teachers he mentions were Nazi party members.

He reminded Hedwig constantly not to address any letters to the school, but his precautions were in vain. On 20 May, he reports that: “The boys are bullying me a lot; it seems they have got wind from somewhere that I am a Mischling.”

In the beginning, Aunt Otti and Kurt’s two displaced uncles helped with his deficient nourishment, when they could get hold of food: “Jews aren’t allowed to buy fruit or meat here,” Kurt writes on 7 May.

Otti offered Kurt a refuge from his troubles on weekends, and subject to the success of her own attempts to escape, offered a solution to the increasingly pressing problem that the school would be closing for summer, leaving Kurt without accommodation.

Until, that is, anonymous anti-Semitic hate mail started to arrive at Otti’s house. Kurt tells his mother that one such letter included a picture of Julius Streicher - Nazi party member and editor of the anti-Semitic journal Der Stürmer.

Such help had to be curtailed because shockingly, as I learned in a note added by Otti to Kurt’s letter, the prime suspect was my grandfather.

I had to revisit previous letters to try to piece together why.

Around that time, Kurt reports that his father demanded that he break off contact with his mother or face consequences - a demand made when (or perhaps because) mother and son were highly vulnerable. When Kurt rejected the demand his father's anger was such that he told Kurt never to contact him again.

In one letter, Kurt writes that his father had described his offer of an “Aryan upbringing” as superior to the one offered by Kurt’s mother. This, despite Hedwig’s secular outlook and the fact that Kurt had been baptised a Catholic, which were inadmissible factors for Nazis.

It appears that my grandfather was now taking his anger to new levels and giving vent to his anti-Semitism.

As no doubt intended, the anonymous letters only aggravated Kurt’s predicament because Otti was forced to stop letting him stay at her house. She feared being denounced to the authorities by Kurt’s father for breaking any of the many anti-Jewish regulations.

Kurt tells Hedwig that he cannot approach his uncles for help because he fears for their safety even more, presumably because unlike Otti they had Jewish spouses.

With nowhere to turn and dwindling financial reserves that also meant his clothes were disintegrating, Kurt writes on 24 May that he would be seeking out a park bench to sleep on.

Almost 1,000 miles away, Hedwig must have been beside herself.

So why did she seem to urge Kurt continually to try to see his father in the face of evidence of intimidation and rejection?

The answer lay in the goal mother and son were each striving towards - a goal that formed the most common subject matter in the letters and one that became increasingly urgent as time passed: Kurt’s escape.

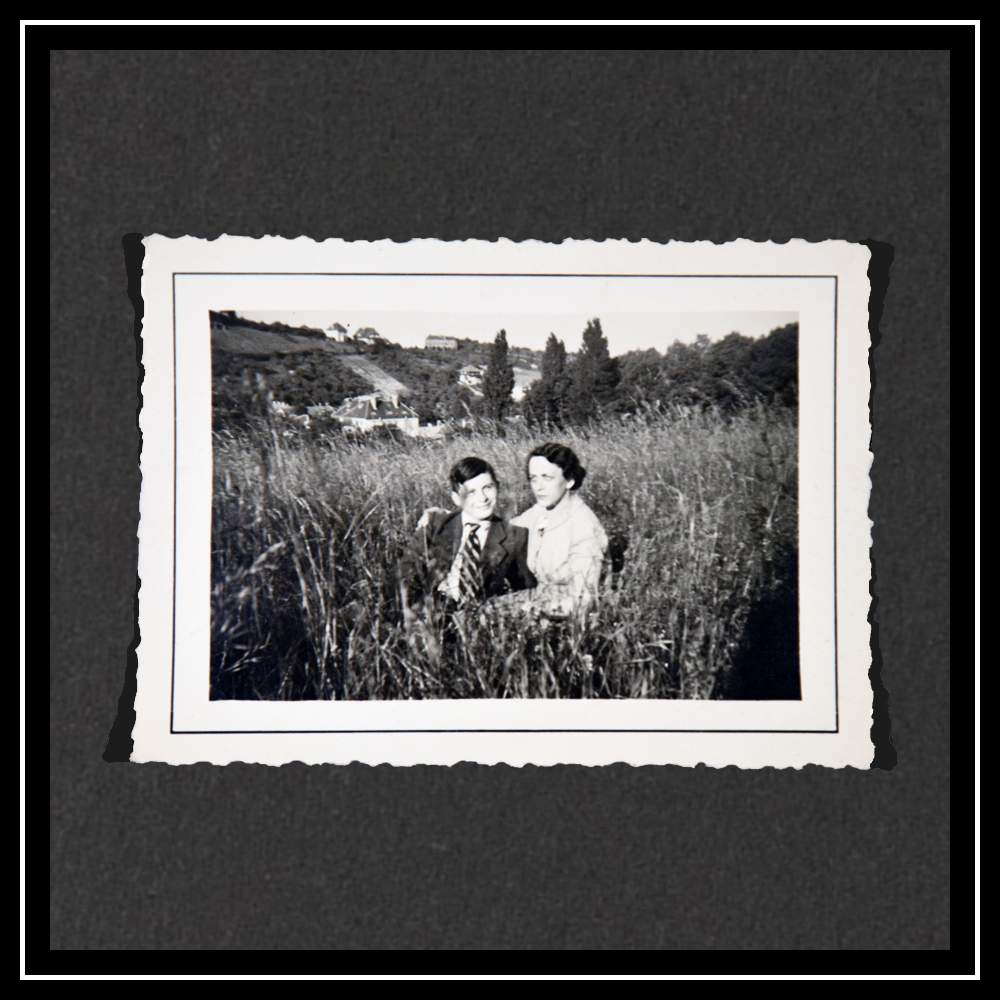

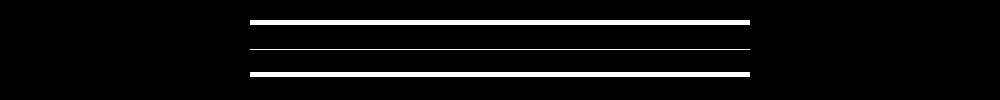

Kurt and aunt Otti in Vienna in April 1939

If there was a plan, it was to try everything and anything to extract Kurt. From the beginning of her exile, Hedwig had been trying to get him a work-based visa and the kind of financial sponsorship necessary for this, or a place on a Kindertransport as her dependant.

She was arguably better placed to do this when based in the UK. But it must have been exceedingly difficult with a full-time job, living in rural isolation and not speaking a word of English.

By 30 April 1939, Hedwig’s employer Mrs Seaton had agreed to help by writing to the Kindertransport committee, sponsoring Kurt and finally setting about finding him a place of work. However, it was two months and many anxious letters before a possible candidate, a farm, would be found.

Kurt desperately needed to get a passport. Without it, any progress his mother made would come to nothing. The problem was that he still needed his father’s permission to travel. Hedwig encouraged Kurt to stay in contact with him to lay the groundwork for the request, but as I had discovered, their relationship was going from bad to worse.

I was on tenterhooks as I waited for the final instalments of letters from the transcriber.

Hedwig with her five siblings and some of their spouses. Sister Helene Kompert (5th from the left) and Ella Müller (8th from the left) both died with their husbands in the Holocaust. In the front row is Hedwig’s mother and Kurt with a sling.

Kurt’s father’s blunt refusal to talk eventually gave way to a promise to sign the relevant papers at the guardianship court after Kurt cornered his father at work. Kurt turned up at the court alone on 9 June full of hope, to find that his father had lied. “This low-life has of course not signed…my father doesn’t care about me,” he writes in a letter on the same day.

An intervention from aunt Otti’s non-Jewish husband Stefan was decisive, but only after he was told that it was “shameful” that an Aryan like him should represent the Jewess Hedwig. Kurt’s father agreed to sign a document that absolved him of any further parental duties or school payments, meaning Stefan could authorise Kurt’s passport.

“A heavy load has just been lifted from me,” writes Kurt on 25 June, and in happy anticipation of a reunion: “I think that you will recognise me: I have become a bit bigger and more manly but don’t yet look like Clark Gable.”

Now the burden was entirely Hedwig’s.

The farm placement had not yet materialised and Kurt pressed his mother to get an answer. On 28 June, a breakthrough made it unnecessary. The Quaker Society of Friends, a key Kindertransport organiser, told Kurt that he would be travelling on 11 July, but only if he could get all of his documents together. Otherwise, the next available place was mid-August, just two weeks before the war that he sensed was coming would start. “I am overjoyed,” he wrote to his mother when the news arrived.

Kurt raced to comply and on 10 July, just one day before his scheduled departure on a Kindertransport, he got his passport. Having already endured parental separation, he was in the unusual position among his travelling companions of steaming towards a reunion.

Most of the other children on the train, along with the almost 10,000 who made the same journey to safety on Kindertransports before war broke out, had, unbeknownst to them, said their final goodbyes before boarding.

With the benefit of hindsight, leaving first was absolutely the right decision. Had Hedwig stayed, Kurt may not have found a place on a Kindertransport, although as a Mischling he would have been spared death, if not discrimination, in Austria.

Wherever he was, Kurt would have been even more alone in the world because Hedwig would have faced the fate of two other sisters who died in Nazi camps.

If at the outset of reading the letters I had expected to learn why Hedwig and Kurt may have found it hard to talk about this period in their lives, then by the end of the 100 pages I had unexpectedly discovered why Kurt may have avoided talking about his father, too.

Hedwig had little choice for a decision that at first seemed callous, and her devotion to Kurt shone through in the letters. But the opposite could be said of my grandfather. I was troubled by the discovery that he was responsible for a great deal of the trauma and almost prevented the reunion.

To cap it all, he had become sympathetic to the hate-filled ideology that takes the ultimate blame for Hedwig and Kurt’s predicament in 1939.

But my most lasting impression from the letters is how an unshakeable bond between mother and son helped them to prevail in dark times so that they could be together again.

Postscript

I later found a chit issued by the Vienna authorities in the 1960s among Hedwig’s papers. She could never face going back but Kurt did, so it must have been from one of his visits.

He had requested his father’s address and it had been provided. Who knows whether they met or what passed between them, but there was clearly unfinished business for Kurt long into adulthood. A great deal of this, no doubt, was from the period that he was alone in Vienna, caught between a Jewish mother and an anti-Semitic father at a time that this paradox had never been so consequential.

Kurt and his cousin (Otti’s daughter) in April 1939 in Vienna.

More can be discovered about the letters in an online exhibition at the Wiener Library, with the full set available to researchers, visiting the library.

Credits:

Author: Nik Pollinger

Editor: Kathryn Westcott

Photos and production: Emma Lynch