As millions of people travel back and forth on Britain’s Victorian rail network, the space below them is teeming with trade; from MOT centres to gin distillers.

But after Network Rail announced the sale of 5,200 units to investment companies, thousands of small and independent firms fear potential rent increases could put their livelihoods in jeopardy.

Here are some of the stories of the businesses that give life to the arches.

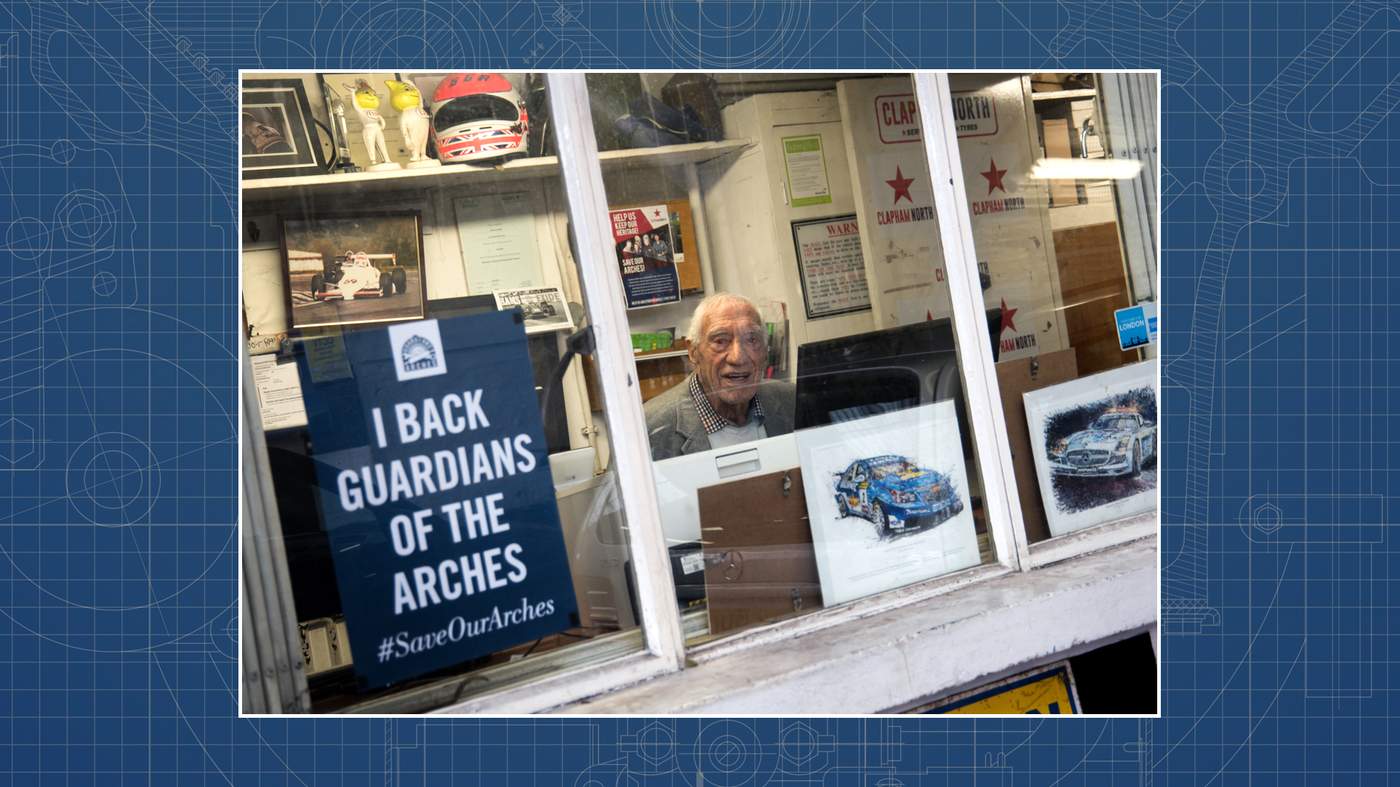

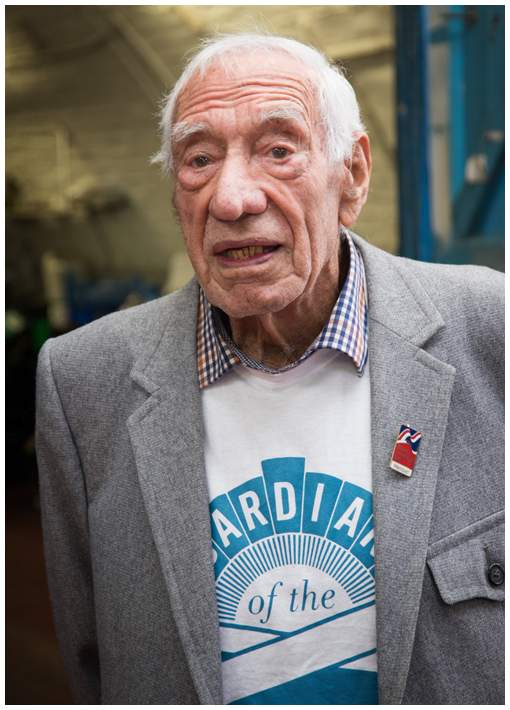

For nearly 60 years, Ronnie Grant has run a business out of the railway arches in Clapham, south London.

As a London cab driver, he and a friend set up a Hackney carriage leasing company in 1960. Now at the age of 93, he runs Clapham North MOT, alongside his son George.

Ronnie says that when he leased the arches he asked British Rail - who owned them at the time - what they could do with them.

"They said basically anything as long as we paid the rent. And we’re still here,” the D-Day veteran proudly says.

Ronnie Grant

“It used to be like a little village. There was a lot of buzz but it feels like now we’re the last people standing.”

Ronnie, a former racing driver who competed alongside a teenage Ayrton Senna in the 1980s, says Network Rail tried to increase the rent from £33,000 a year to £147,000 several years ago.

But he and his son fought off the increase.

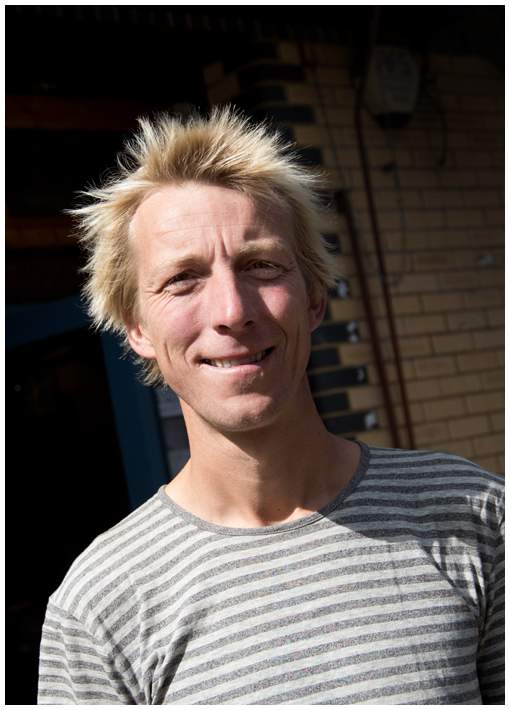

George Grant

“It’s a big battle,” says George. “My dad’s had quite a few battles in his life, certainly in World War Two. But this feels like one of the toughest ones.”

Ronnie remains defiant and insists he has to keep working.

What happens is you retire and then you die - that’s why I’m not retiring.”

George has become involved in Guardians Of The Arches, a group set up to dispute Network Rail’s sell-off of its archway stock.

“The archways are one of the rare opportunities in the UK where you can have small businesses that nurture and encourage new ways of working,” he says.

“We would have been a poorer place if people like my dad didn’t set up businesses in the arches. We’re trying to save a whole ecosystem, and we will not waver.”

Network Rail says selling the arches means they will have more money to spend on improving rail infrastructure.

Katie Cullen and her husband Steven Warren have a business selling craft beers and high-quality meats under one roof.

The business partners have been running Block and Bottle in Gateshead, Tyne and Wear, since April 2017.

“It’s a new idea, we’re the first of our kind,” 30-year-old Katie says.

They initially wanted to set up in London but found it was going to be too expensive.

The reason why we’ve been able to set up the business the way we have is because of the rent we pay.”

Katie says the archway’s proximity to the city centre has helped the pair’s butcher and bottle shop get passing trade and expand after just 20 months.

And she believes the arches have helped regenerate the area, attracting businesses that might never have got off the ground otherwise.

Two companies, Telereal Trillium and Blackstone Group, have agreed to buy thousands of the arches. They say they will provide a "supportive environment in which these businesses can flourish on a long-term basis".

But Katie and Steve are still worried about the future of their fledgling business.

It’s a concern, they say we’re not going to get kicked out and the leases will transfer over. But for people who aren’t on long leases that's a worry.

“I personally think the sale is short-sighted because the arches are providing such a huge income for Network Rail every year.

“It’s cutting their nose off to spite their face, it’s fixing a short-term problem but creating a much larger long-term problem.”

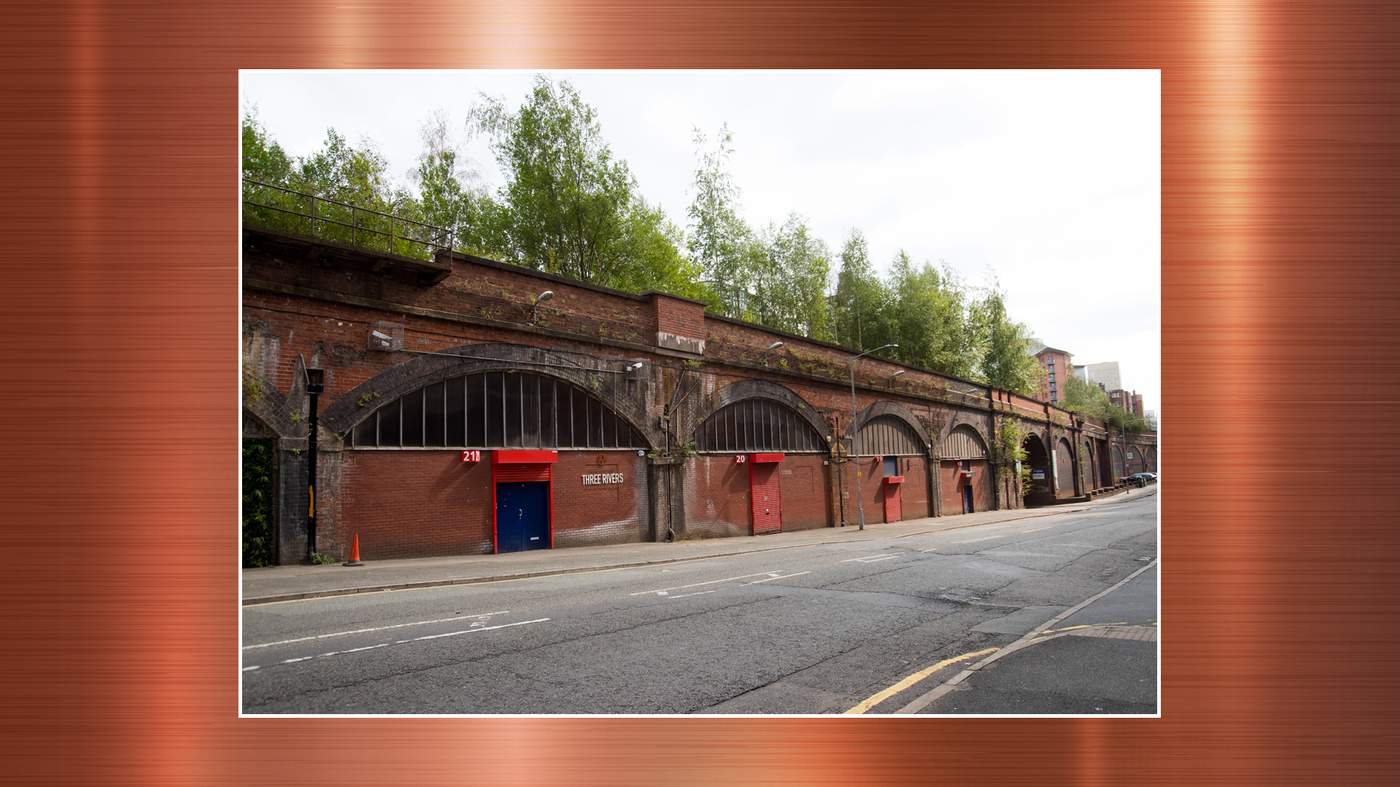

In 2015 Dave Rigby, Mike Hughes, Louise Rivers-Hull and her husband Greg Hull set up Manchester Three Rivers gin distillery. It’s the first micro-distillery to be located in the city, a stone’s throw away from Victoria Station.

Dave, the master distiller, has a very personal connection with the arches. “What’s nice for me is that my grandad used to work on the lines above us as a safety officer 70 years ago, and now I’m making booze under the archway.

“Aside from that it really is a suitable, affordable place to work. We couldn’t have done it anywhere else.”

The group has two arches, one where the gin is made and the other to bottle the product. Both arches also have so-called "gin schools" where people can distil their own gin from raw ingredients.

But the four friends and business partners fear the sale of the arches could put their factory floor, and gin experience, in jeopardy.

Louise Rivers-Hull

“Obviously it’s a worry, it’s disappointing to be put in this situation,” says Louise, who previously ran her own PR firm. “I wound down my own business to work on this, because this is where my passion lies.

“Communication from Network Rail has been really poor. It’s a case of if you don’t speak up, then nobody else will for you.”

Mike adds: “We’re a small business, we’re the backbone of this country and we should be applauded, not hindered. We spent our lives decking this place out, and we don’t want that hard work to go to waste.”

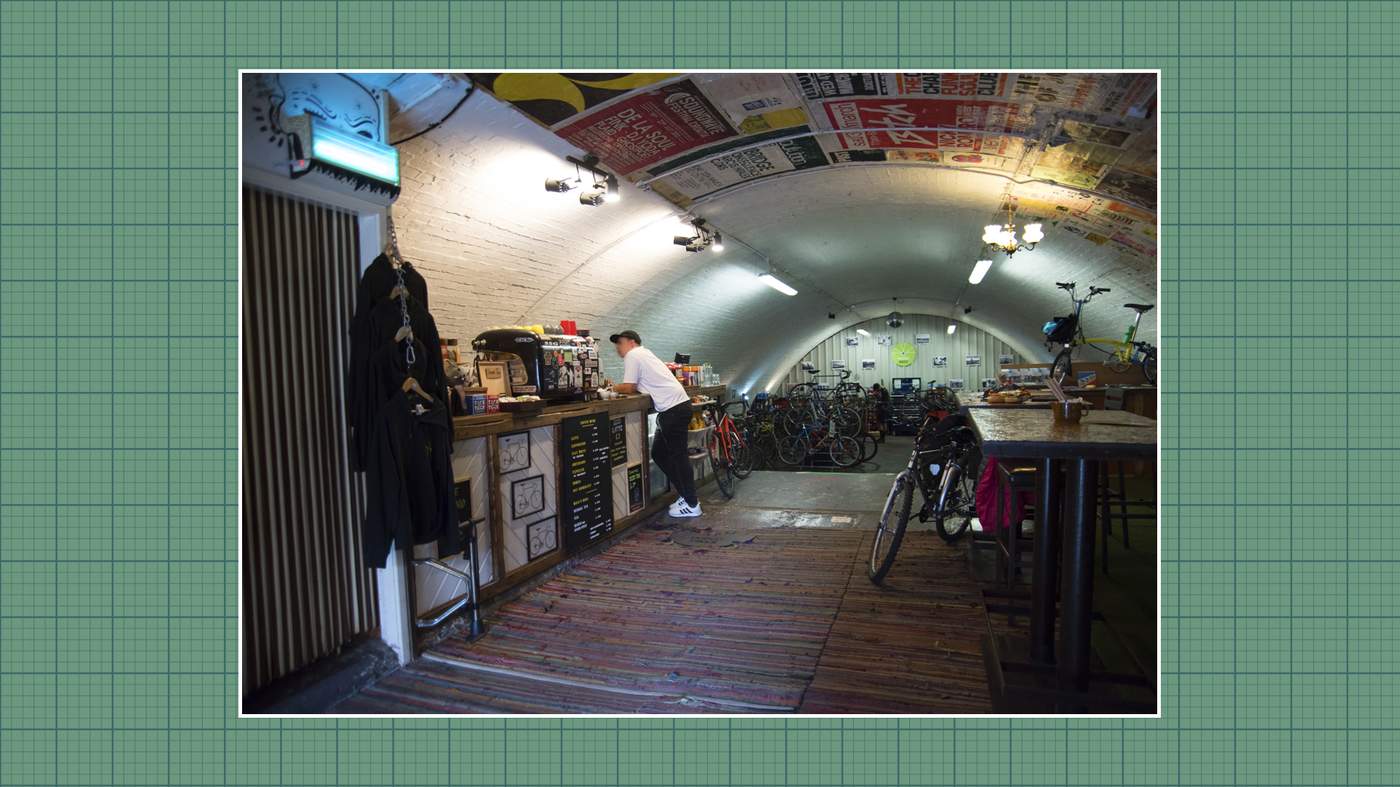

Down the road from Manchester Three Rivers, Popup Bikes stands unassumingly, a table and a set of chairs outside its entrance.

“It’s more than a bike repair shop,” says Jack Dobiecki. “It’s a place for the bike courier community to meet.”

Minutes away from Victoria Station, the shop provides on-the-spot repairs for up to 100 bikes a day and doubles as a community hub with its coffee shop and reading area.

Jack Dobiecki

Jack, 25, began working at the shop after being a courier.

“I was in and out of here all the time, working 10-hour days on the streets. I seem to have fallen into it but it’s a really nice working environment, everyone’s really friendly.”

Jack says there’s a camaraderie between businesses in the arches that gives a real sense of community.

“The fact that we’re a small independent business in - what will become - a very built-up area in the next five years, makes it very important that we stay. But that’s not exactly in our hands.

“So much work has gone into making this shop what it is, we don’t want to move.”

In 2011 Ben MacKinnon baked bread as a hobby. “I intended to work on my own two days a week,” he says.

Now seven years later E5 Bakehouse takes up three railway arches in Hackney, east London, and employs 90 people.

“The arches have given us the chance to grow in the slow, haphazard way that we have. The arches have given us the opportunity to evolve.

“Put simply, there was nowhere else I would have been able to start my business.”

Ben MacKinnon

Ben, 39, feels wedded to the area. His grandparents ran an apron and linen shop in Church Street, not far from his bakery.

Alongside his family connection, he thinks there’s something romantic about the arches.

“You don’t think about it often, but you hear the shudders [of the trains] and you then find yourself thinking of the people racing backwards and forwards.

“It’s a unique thing, ribbons of railway arches running across the capital, really decent spaces that allow the manufacturing businesses somewhere to operate.”

But is the sell-off of the arches a worry for Ben?

On the one hand, he says, he's happy to see Network Rail go. But on the other, he says there’s a risk that whoever’s going to be taking it on will be "hell-bent on maximising profit and even looking at selling on the asset in a few years”.