March was going to be the decisive month - the days that would transform the UK.

I wanted to hear what people had to say and chose four places that each showed a distinct aspect of Brexit.

This isn’t an exhaustive or comprehensive tour of the UK - I’ve visited only two of the four constituent nations.

This piece doesn't include Wales and Northern Ireland. The distinctive nature of their Brexit debates merits separate analysis.

I started in Southampton.

For generations, this was where immigrants and visitors alike first set foot on English soil. It is where they first encountered the British, after disembarking from one of the great ocean-going vessels that shaped the history and character of this port city.

In the 1930s, the writer and social commentator JB Priestley called Southampton Britain’s “bay window on the wide world”. Southampton Water was one of Britain’s gateways to a trading empire that circled the globe.

View of Southampton's Ocean Terminal from the Queen Mary, 1950

And I wanted to start here because it’s where my own working life as a news reporter began.

I came here in the mid-80s to learn my trade. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was radically reshaping Britain. Traditional, mass-employment industries were dying. Dole queues had been lengthening. Like many Scots of my generation I headed south looking for a break, in a part of the country where there still seemed to be opportunity.

I’d come from a brief spell working in Glasgow, another port city that had thrived as a trading and industrial hub in the heyday of Imperial Britain.

Allan Little as a young man

The difference astonished me. Much of industrial Glasgow was sinking into dereliction and despair but in Southampton there was money, investment, growth. Southampton was managing the transition from the age of Empire to the age of Europe with a dynamic self-confidence that was unlike anything I had seen.

This part of south central England had also embraced the prevailing values of that decade: privatisation, deregulation, enterprise. The patch I worked covered 20 parliamentary constituencies. All of them had a Tory MP.

I did story after story on men who’d been laid off as the shipyards and city-centre docks had closed down, but who had used their redundancy money to start their own businesses and employ others.

Southampton never ceased to be a global trading hub, but it was now well-placed to benefit from a Europe that was tearing down barriers to trade between its member states.

I started in Southampton.

For generations, this was where immigrants and visitors alike first set foot on English soil. It is where they first encountered the British, after disembarking from one of the great ocean-going vessels that shaped the history and character of this port city.

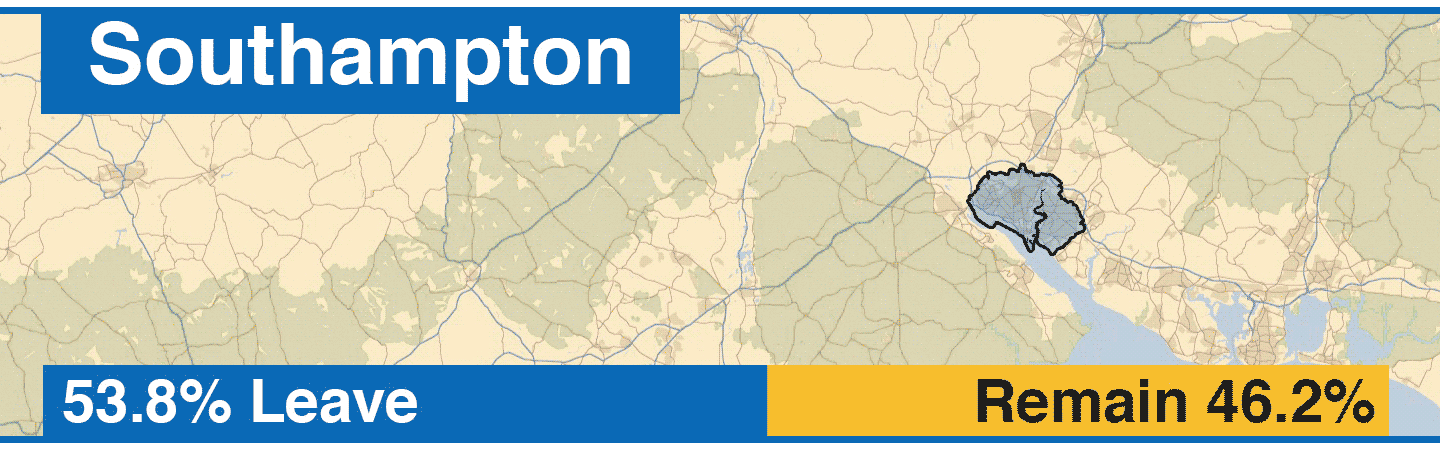

Southampton

In the 1930s, the writer and social commentator JB Priestley called Southampton Britain’s “bay window on the wide world”.

Southampton Water was one of Britain’s gateways to a trading empire that circled the globe.

View of Southampton's Ocean Terminal from the Queen Mary, 1950

And I wanted to start here because it’s where my own working life as a news reporter began.

I came here in the mid-80s to learn my trade. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was radically reshaping Britain. Traditional, mass-employment industries were dying. Dole queues had been lengthening. Like many Scots of my generation I headed south looking for a break, in a part of the country where there still seemed to be opportunity.

I’d come from a brief spell working in Glasgow, another port city that had thrived as a trading and industrial hub in the heyday of Imperial Britain.

Allan Little as a young man

The difference astonished me.

Much of industrial Glasgow was sinking into dereliction and despair but in Southampton there was money, investment, growth. Southampton was managing the transition from the age of Empire to the age of Europe with a dynamic self-confidence that was unlike anything I had seen.

This part of south central England had also embraced the prevailing values of that decade: privatisation, deregulation, enterprise. The patch I worked covered 20 parliamentary constituencies. All of them had a Tory MP.

I did story after story on men who’d been laid off as the shipyards and city-centre docks had closed down, but who had used their redundancy money to start their own businesses and employ others.

Southampton never ceased to be a global trading hub, but it was now well-placed to benefit from a Europe that was tearing down barriers to trade between its member states.

1980s waterfront housing by the Itchen Bridge, Southampton

From our newsroom window we could see former industrial waterfronts being transformed into smart and expensive new housing developments - some of them properties with a private berth to moor a yacht.

Margaret Thatcher spent the last day of her 1983 re-election campaign here, and across the Solent on the Isle of Wight, precisely because it had come to represent, for her, what free-market reform could deliver: wealth creation freed from the dead hand of the state.

Margaret Thatcher, Isle of Wight, 8 June 1983

Southampton people were not rich. But this was a far cry from Glasgow.

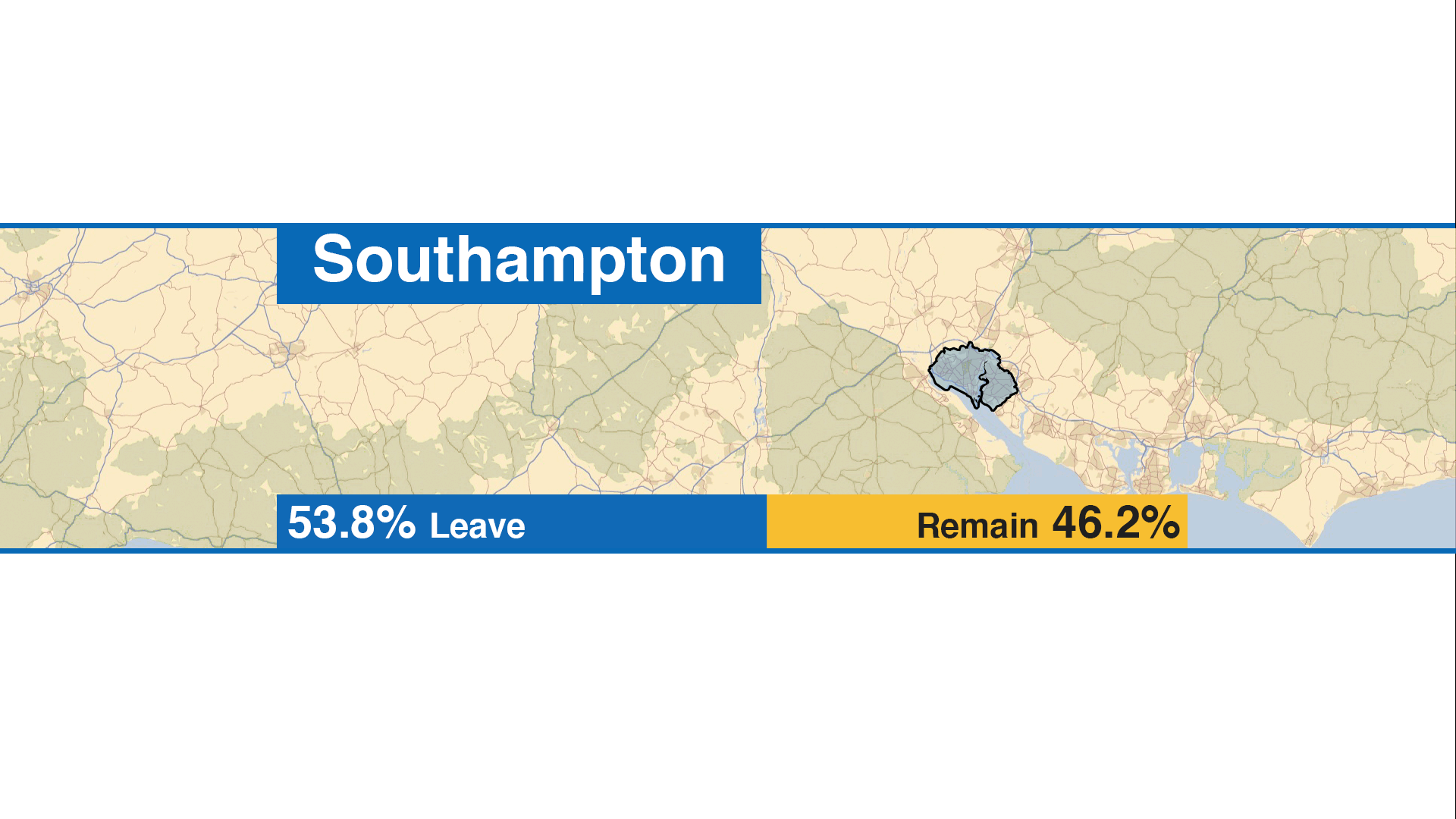

Like most of England, Southampton voted to leave the EU in 2016. The margin was 54% to 46%, which was about the average for England as a whole.

After the referendum, London-based news organisations sent reporters like me north, to the post-industrial heartlands that represented an England that had been - in the parlance of my trade - “left behind” by a globalised economy. But Southampton had not been left behind. Far from it. It had been swept along by the forces of globalisation for three decades.

Danny Babey is in his early 40s and runs his own upholstering company. A lot of his work is on the water, refurbishing private yachts. He voted to leave the EU.

Danny Babey

“Why can’t we make our own rules?” he says as he noses his own yacht out of harbour. We chug past the vast container port that has grown up to the west of the city. “It’s not easy being told what to do by another country.”

I took a mental note of this, knowing that I planned to end my journey in Scotland, which voted 62% to remain but will have to leave with the rest of the UK regardless.

Danny tells me he’d recently sent 10 workers to do a job in Marseilles. “I suppose I might have to think about sorting visas for that sort of thing now,” he says. “But I hope the transition will be smooth.”

“Did you think about that when you voted to leave?” I ask him.

“Not really,” he says, “because I wasn’t doing that work then. I suppose that work might go to another company now, one that’s inside the European Union and yes, that would concern me. But I always take the view that something else will turn up.”

In the city centre that evening, Tomasz Dyl is in a bar with a dozen friends and colleagues, drinking champagne and slicing birthday cake. It is 11 years to the day since he founded his own marketing company. It now employs 10 people full time and has just opened an office in London’s Oxford Street.

Tomasz Dyl

Tomasz came to Southampton 15 years ago at the age of 13 without speaking a word of English. His Polish parents took low-paying jobs to give their children a better start, in a wealthier country.

Tomasz, a beneficiary of freedom of movement between member states, voted to remain and was sure Southampton would too.

Why didn’t it?

“At one point, Polish was Southampton’s second language,” he tells me, acknowledging the role that high levels of immigration played in the way many people voted. “The Poles were 10% of the population of the city. Most have done well. They started their own businesses. They’ve brought a lot to this country.”

For Tomasz, the immigrant experience has been a happy one. He talks about his adopted city in the first person plural. “We’re a very welcoming city,” he says. “We’re a port city. We’re used to people coming in and going out all the time.” He has almost no personal experience of anti-immigrant sentiment in a city he clearly loves.

Pearline Hingston is also an immigrant.

Pearline Hingston

She came to Britain at the age of 11 from her native Jamaica, where she was born to a family of Indian descent.

Her identity is shaped by the Commonwealth, she tells me, and she has been campaigning to leave the European Union for years.

She is a UKIP branch secretary.

“We have waited long enough. We should leave, even on a no-deal. Britain can trade globally. We can trade globally on WTO terms,” she says.

“If the EU doesn’t want to stay friends, if it wants the UK to impose tariffs on its goods, then that’s its choice.”

Pearline - who also voted Out in the 1975 referendum to decide if the UK would remain in the EEC as it was then - is convinced Brexit is being sabotaged.

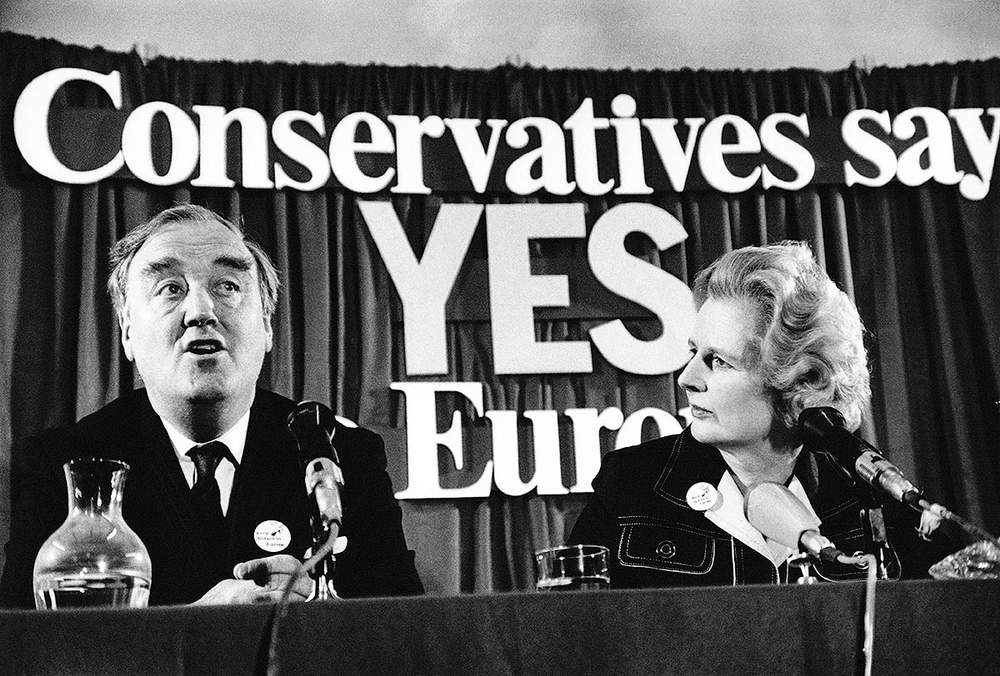

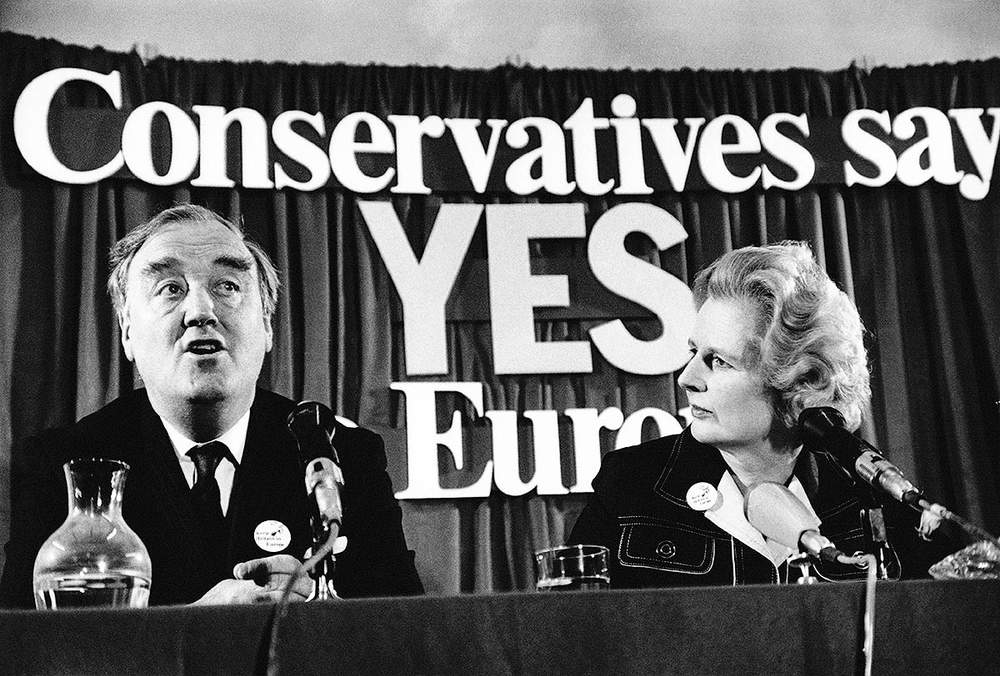

Conservative leader Margaret Thatcher during the referendum campaign on Europe, June 1975

“The EU has the upper hand,” she says, “and there have been people here in parliament who have been tripping over to Brussels having private meetings, and they have become anti-British and anti-democratic in their behaviour. They should accept the referendum and not pull the rug from under Mrs May.”

For many here, Southampton’s Leave vote was not primarily about immigration. There is a “something will turn up” self-confidence - some might say complacency - about this England that is borne of experience: the experience of 40 years in which, compared with the England I’m headed to next, something usually has turned up.

It wasn't just the England of the “left-behinds” that tipped the scales for Leave in 2016. There was a numerically significant chunk of Leave votes from a non-metropolitan England that is relatively comfortably off.

This is what I take away from Southampton - if you’re a Remainer, it’s too simple to blame the poor or the North. A critical mass of Leave sentiment is in the South.

From our newsroom window we could see former industrial waterfronts being transformed into smart and expensive new housing developments - some of them properties with a private berth to moor a yacht.

1980s waterfront housing by the Itchen Bridge, Southampton

Margaret Thatcher spent the last day of her 1983 re-election campaign here, and across the Solent on the Isle of Wight, precisely because it had come to represent, for her, what free-market reform could deliver: wealth creation freed from the dead hand of the state.

Southampton people were not rich. But this was a far cry from Glasgow.

Like most of England, Southampton voted to leave the EU in 2016. The margin was 54% to 46%, which was about the average for England as a whole.

After the referendum, London-based news organisations sent reporters like me north, to the post-industrial heartlands that represented an England that had been - in the parlance of my trade - “left behind” by a globalised economy. But Southampton had not been left behind. Far from it. It had been swept along by the forces of globalisation for three decades.

Danny Babey is in his early 40s and runs his own upholstering company. A lot of his work is on the water, refurbishing private yachts. He voted to leave the EU.

Danny Babey

“Why can’t we make our own rules?” he says as he noses his own yacht out of harbour. We chug past the vast container port that has grown up to the west of the city. “It’s not easy being told what to do by another country.”

I took a mental note of this, knowing that I planned to end my journey in Scotland, which voted 62% to remain but will have to leave with the rest of the UK regardless.

Danny tells me he’d recently sent 10 workers to do a job in Marseilles. “I suppose I might have to think about sorting visas for that sort of thing now,” he says. “But I hope the transition will be smooth.”

“Did you think about that when you voted to leave?” I ask him.

“Not really,” he says, “because I wasn’t doing that work then. I suppose that work might go to another company now, one that’s inside the European Union and yes, that would concern me. But I always take the view that something else will turn up.”

In the city centre that evening, Tomasz Dyl is in a bar with a dozen friends and colleagues, drinking champagne and slicing birthday cake. It is 11 years to the day since he founded his own marketing company. It now employs 10 people full time and has just opened an office in London’s Oxford Street.

Tomasz Dyl

Tomasz came to Southampton 15 years ago at the age of 13 without speaking a word of English. His Polish parents took low-paying jobs to give their children a better start, in a wealthier country.

Tomasz, a beneficiary of freedom of movement between member states, voted to remain and was sure Southampton would too.

Why didn’t it?

“At one point, Polish was Southampton’s second language,” he says, acknowledging the role that high levels of immigration played in the way many people voted. “The Poles were 10% of the population of the city. Most have done well. They started their own businesses. They’ve brought a lot to this country.”

For Tomasz, the immigrant experience has been a happy one. He talks about his adopted city in the first person plural. “We’re a very welcoming city,” he says. “We’re a port city. We’re used to people coming in and going out all the time.” He has almost no personal experience of anti-immigrant sentiment in a city he clearly loves.

Pearline Hingston is also an immigrant.

Pearline Hingston

She came to Britain at the age of 11, from her native Jamaica, where she was born to a family of Indian descent. Her identity is shaped by the Commonwealth, she tells me, and she has been campaigning to leave the European Union for years. She is a UKIP branch secretary.

“We have waited long enough. We should leave, even on a no-deal. Britain can trade globally. We can trade globally on WTO terms,” she says.

“If the EU doesn’t want to stay friends, if it wants the UK to impose tariffs on its goods, then that’s its choice.”

Pearline - who also voted Out in the 1975 referendum to decide if the UK would remain in the EEC as it was then - is convinced Brexit is being sabotaged.

Conservative leader Margaret Thatcher (r) during the referendum campaign on Europe, June 1975

“The EU has the upper hand,” she says, “and there have been people here in parliament who have been tripping over to Brussels having private meetings, and they have become anti-British and anti-democratic in their behaviour. They should accept the referendum and not pull the rug from under Mrs May.”

For many here, Southampton’s Leave vote was not primarily about immigration. There is a “something will turn up” self-confidence - some might say complacency - about this England that is borne of experience: the experience of 40 years in which, compared with the England I’m headed to next, something usually has turned up.

It wasn't just the England of the “left-behinds” that tipped the scales for Leave in 2016. There was a numerically significant chunk of Leave votes from a non-metropolitan England that is relatively comfortably off.

This is what I take away from Southampton - if you’re a Remainer, it’s too simple to blame the poor or the North. A critical mass of Leave sentiment is in the South.

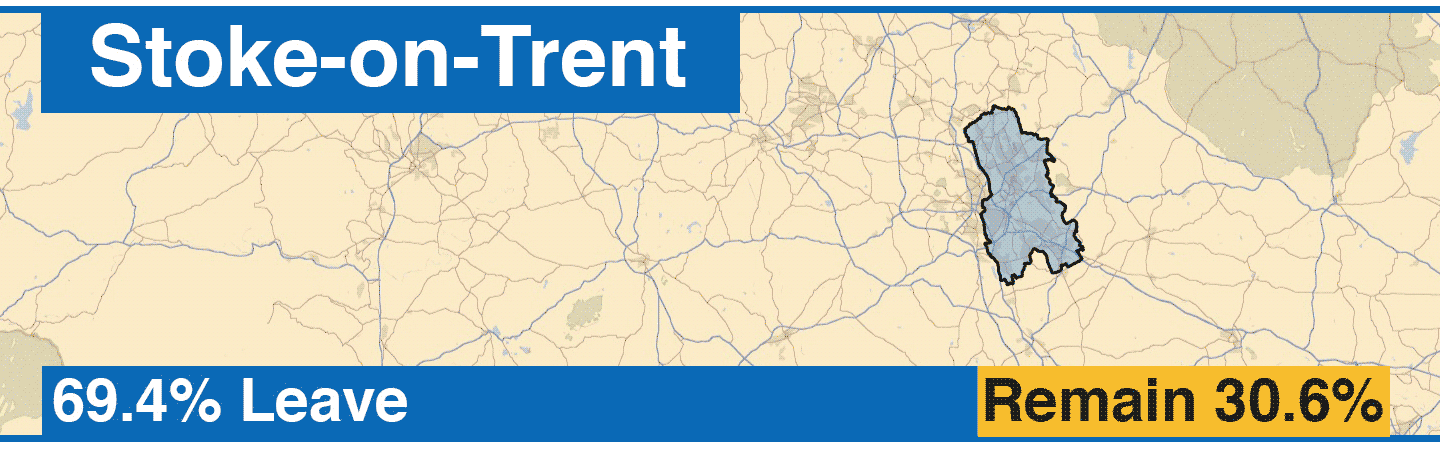

In Stoke-on-Trent, there’s not much of the confidence I encountered in Southampton.

What there is - and you don’t have to spend much time here to get a sense of it - is a fierce civic pride in the character and traditions of the city. Stoke-on-Trent is not much of a magnet for internal migration. Most people who live here are from here. It feels like a place of neighbourliness, of a shared sense of identity.

It sits at the heart of a part of England that shares its very name with the industry that is the source of that pride: the Potteries.

Pots, pits and steel; these were the three industrial pillars on which Stoke-on-Trent was built. Coal and steel have gone, and the Potteries reduced to a fraction of what they once were.

Waste incinerator and the A500, Stoke-on-Trent

I took a walk not far from the city centre. Opposite a neat row of brick-built terraced houses, I walked past a derelict industrial plant. I stopped to gaze through rusting chained-up fencing at the soot-black bricks of the distinctive funnel-shaped kiln chimneys and warehouses that once produced tableware for half the world.

Stoke-on-Trent, like much of industrial England, is a place that takes pride in the worth and virtue of honest work. But decades of industrial decline and years of “austerity” have had a visible impact here. It has swept away much of the economic activity that was the source of that pride.

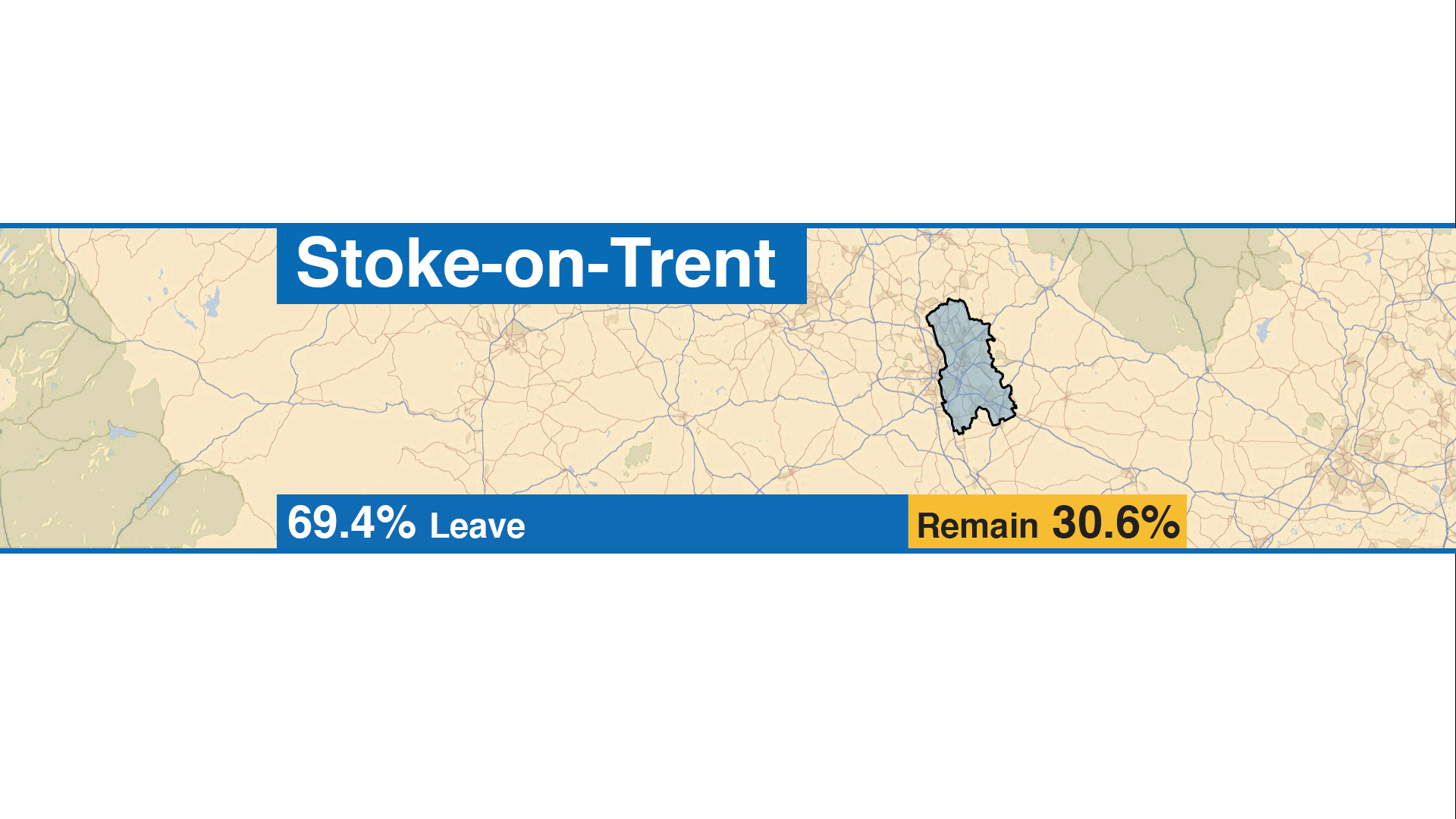

The people here voted by nearly 70% to leave - one of the highest margins in the country.

“People who live in London, in places of power, don’t know anything about Stoke-on-Trent,” Danny Flynn tells me. “They just make assumptions that it’s not a very nice place, where those rough people live.”

Danny Flynn

And he performs a little parody of what he sees as the judgmental, liberal middle class: “Oh those uneducated white working-class people - how very dare they vote Brexit?”

Danny runs the Stoke YMCA. He provides secure accommodation for vulnerable young adults and provides them with training that helps to turn their lives around and get them into work.

He voted Remain - reluctantly he says. “I can see why people in Stoke would think, ‘Never mind Brussels, London’s got nothing to do with us!’ So I could see why it happened, but I think it was more a general protest vote of not being included in the game called Great Britain.”

That sense - that Stoke feels excluded - is everywhere. This is a city that globalisation has left behind.

Graham Eagles has a stall at Tunstall market selling pet supplies. At the weekends, he runs dog training courses in a local community hall. He voted Leave.

Graham Eagles

“Eventually I think the country could be run a lot better, more self sufficient,” he says.

“We could rely less on other countries. We could do it ourselves like we used to, a long time ago obviously, but we did. This country has lost its backbone a little bit I think, and that’s what it needs to get back and stand strong.”

It is a theme that runs through much of the pro-Leave sentiment I heard expressed in the six towns that constitute this city at the heart of The Potteries: the belief that Britain should recapture some hard-to-define quality that it once had - but has lost.

But go further down the age demographic and that yearning for the lost certainties of the past diminishes. Natalie Willatt, who’s 24, left the city to take a degree in photography in Leeds.

Despite the broader range of opportunities the great cities of the North have to offer, she came home after graduating out of love for her home city. Across the country, just over 70% of 18 to 24-year-olds who voted in the referendum backed Remain.

Natalie Willatt

I ask her whether she could understand why so many people here voted Leave.

“I can understand why so many people are unhappy,” she tells me. “Yes, you can’t get a doctor’s appointment but that’s because the NHS is underfunded, not because there’s an immigrant taking your space.

“So I believe actually it’s austerity and underfunding of things that are causing these issues that people might blame immigrants for. So I can understand why people are angry, I just think they’re blaming the wrong people for it.”

Stoke-on-Trent illustrates one of the paradoxes of the Leave victory - that so many traditional Labour-voting communities, and especially those plunged into hardship by the collapse of industry, should have voted for a policy championed most vociferously by the right-wing of the Conservative Party.

One of the consequences of the collapse of the traditional industries was the erosion of the power of the trade unions and the role they played in people’s lives.

Trade union officials were a constant presence in those communities - in the workplace, agitating for improvements in working conditions, taking up the cause of workers who believed they’d been unjustly treated at work, in the social clubs and bars where people gathered in their down time.

Local Labour activists that had emerged from that movement were known by local people, and often sent to represent them at Westminster.

Tony Blair's Labour election victory in 1997

Eighteen years of Conservative government changed that.

The trade union movement was stripped of the power it once had. The workplaces that had sustained the Labour movement disappeared. Labour at Westminster rebranded itself.

“New Labour” set out to appeal to prosperous Middle England. It had to win back seats in places like Southampton. The party at Westminster came to see “cloth-cap politics” - the politics of class grievance - as a vote loser.

The number of genuinely working-class MPs on the Labour benches gradually diminished.

A new generation of clever young men and women with university backgrounds emerged - a caste of professional politicians who had not come from the communities that had been devastated by the loss of their industries.

The Labour voices raised in parliament sounded less and less like those of the people they represented.

UKIP poster in Stoke-on-Trent, 2017

In this context, UKIP was able to make inroads into territory that had always been loyally Labour.

Not far from Graham Eagles’ pet products stall, I find Shirley Ray. She’s been styling hair here for 20 years. Her salon is busy.

One woman in the chair is having her roots done ahead of a trip to Australia. Two others, both retired, are waiting patiently. There’s not much disagreement between these women. They voted Leave and they want out.

Shirley voted UKIP at the last election and is an admirer of Nigel Farage.

Shirley Ray

“I don’t feel proud to be British any more,” she says, when I ask her about the ongoing paralysis at Westminster. “I think we’re the laughing stock of the world. I think we’re being seen as a very weak country,” she says.

“We’ll put up with anything, just take anything that’s thrown at us. And I think we need to get cracking on making this country great again. To be honest I’ve got no confidence in any of the MPs at all. I just want out.”

One of her customers is Patricia Shrigley. “I can’t see us coming out to be honest, because Westminster doesn’t want it. And I think that would be very unfair.”

Patricia Shrigley

I ask her how she’d feel if Britain ended up staying in the EU. “I wouldn’t vote again,” she says. “That would be me finished. Because it’s supposed to be a democracy, and we’ll just be ignored won’t we?”

It chimes, back at the pet supplies stall, with Graham Eagles’ sense of dejected resignation. “People are getting fed up about voting,” he says. “It’s pointless voting because it gets us nowhere. A lot of people will feel the same - what’s the point?”

If there was a second referendum, Natalie Willatt would vote - again - to remain.

“I believe people voted to leave because they wanted something to change, because they’re sick of how it is,” she says. “And it’s only going to change for the worse. So that’s the bit I’m sad about - that these communities of brilliant people still aren’t going to get anything better. I think that’s ultimately what they wanted out of Brexit, and they’re not going to get it. This is incredibly sad.”

That is Danny Flynn’s view, too.

“My biggest fear - because the economy will take a kick, even the Brexit people admit that don’t they? - is that working-class people in cities like Stoke will suffer more than any other people in the country,” he says.

“Working-class people will pay again like working-class people have paid for austerity, like working-class people paid for the bankers’ bonuses, to be frank.”

Stoke-on-Trent illustrates one of the paradoxes of the Leave victory - that so many traditional Labour-voting communities, and especially those plunged into hardship by the collapse of industry, should have voted for a policy championed most vociferously by the right-wing of the Conservative Party.

One of the consequences of the collapse of the traditional industries was the erosion of the power of the trade unions and the role they played in people’s lives.

Trade union officials were a constant presence in those communities - in the workplace, agitating for improvements in working conditions, taking up the cause of workers who believed they’d been unjustly treated at work, in the social clubs and bars where people gathered in their down time.

Local Labour activists that had emerged from that movement were known by local people, and often sent to represent them at Westminster.

Eighteen years of Conservative government changed that. The trade union movement was stripped of the power it once had. The workplaces that had sustained the Labour movement disappeared. Labour at Westminster rebranded itself.

“New Labour” set out to appeal to prosperous Middle England. It had to win back seats in places like Southampton. The party at Westminster came to see “cloth-cap politics” - the politics of class grievance - as a vote loser.

The number of genuinely working-class MPs on the Labour benches gradually diminished.

A new generation of clever young men and women with university backgrounds emerged - a caste of professional politicians who had not come from the communities that had been devastated by the loss of their industries.

The Labour voices raised in parliament sounded less and less like those of the people they represented.

In this context, UKIP was able to make inroads into territory that had always been loyally Labour.

Not far from Graham Eagles’ pet products stall, I find Shirley Ray. She’s been styling hair here for 20 years. Her salon is busy.

One woman in the chair is having her roots done ahead of a trip to Australia. Two others, both retired, are waiting patiently. There’s not much disagreement between these women. They voted Leave and they want out.

Shirley voted UKIP at the last election and is an admirer of Nigel Farage.

Shirley Ray

“I don’t feel proud to be British any more,” she says, when I ask her about the ongoing paralysis at Westminster. “I think we’re the laughing stock of the world. I think we’re being seen as a very weak country,” she says.

“We’ll put up with anything, just take anything that’s thrown at us. And I think we need to get cracking on making this country great again. To be honest I’ve got no confidence in any of the MPs at all. I just want out.”

One of her customers is Patricia Shrigley. “I can’t see us coming out to be honest, because Westminster doesn’t want it. And I think that would be very unfair.”

Patricia Shrigley

I ask her how she’d feel if Britain ended up staying in the EU. “I wouldn’t vote again. That would be me finished. Because it’s supposed to be a democracy, and we’ll just be ignored won’t we?”

It chimes, back at the pet supplies stall, with Graham Eagles’ sense of dejected resignation. “People are getting fed up about voting,” he says. “It’s pointless voting because it gets us nowhere. A lot of people will feel the same - what’s the point?”

If there was a second referendum, Natalie Willatt would vote - again - to remain.

“I believe people voted to leave because they wanted something to change, because they’re sick of how it is,” she says.

“And it’s only going to change for the worse. So that’s the bit I’m sad about - that these communities of brilliant people still aren’t going to get anything better. I think that’s ultimately what they wanted out of Brexit, and they’re not going to get it. This is incredibly sad.”

That is Danny Flynn’s view, too. “My biggest fear - because the economy will take a kick, even the Brexit people admit that don’t they? - is that working-class people in cities like Stoke will suffer more than any other people in the country,” he says.

“Working-class people will pay again like working-class people have paid for austerity, like working-class people paid for the bankers’ bonuses, to be frank.”

The post-industrial heartlands, traditional fortresses of Labour solidarity, are not in themselves the problem for the Labour Party - as most continue to return Labour MPs.

But they are where Labour’s single biggest challenge begins.

Most Labour members, and most Labour voters, support Remain, and many want the party to back a second referendum. But most Labour MPs sit in seats that voted Leave.

To win an election, the party would have to win over Leave-supporting seats.

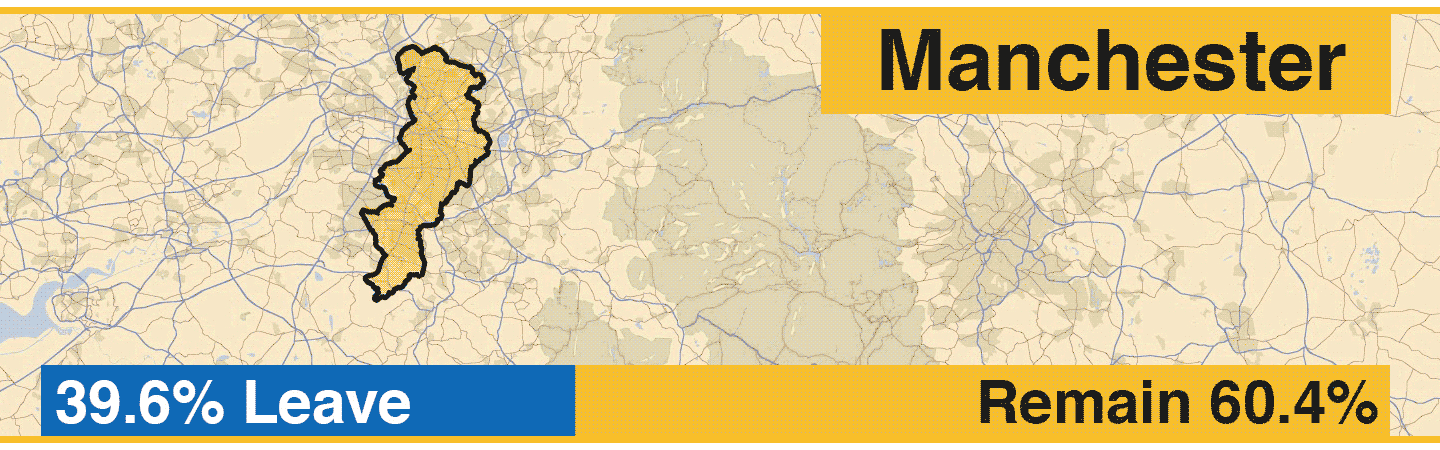

Manchester

Brexit has driven a fracture through both the two big Westminster parties. The divide in the House of Commons might still, formally, be between a Conservative government and a Labour-dominated opposition. But in the country, politics has realigned. The divide out here, beyond the Westminster bubble, is between Remainers and Leavers.

Both main parties are trying to ride two horses that are pulling in opposite directions. Mrs May has spent much of the past two years negotiating not with the European Union, but with her own party.

My next stop was Greater Manchester, where it’s not hard to see that the Labour Party is just as deeply riven.

The bus from Stoke-on-Trent to Manchester doesn’t take long. It’s not much more than a hop. But central Manchester feels a world away.

Manchester

Everywhere you look there is dynamic regeneration. It shines at you in concrete, steel and glass. Here, there is opportunity for an educated workforce.

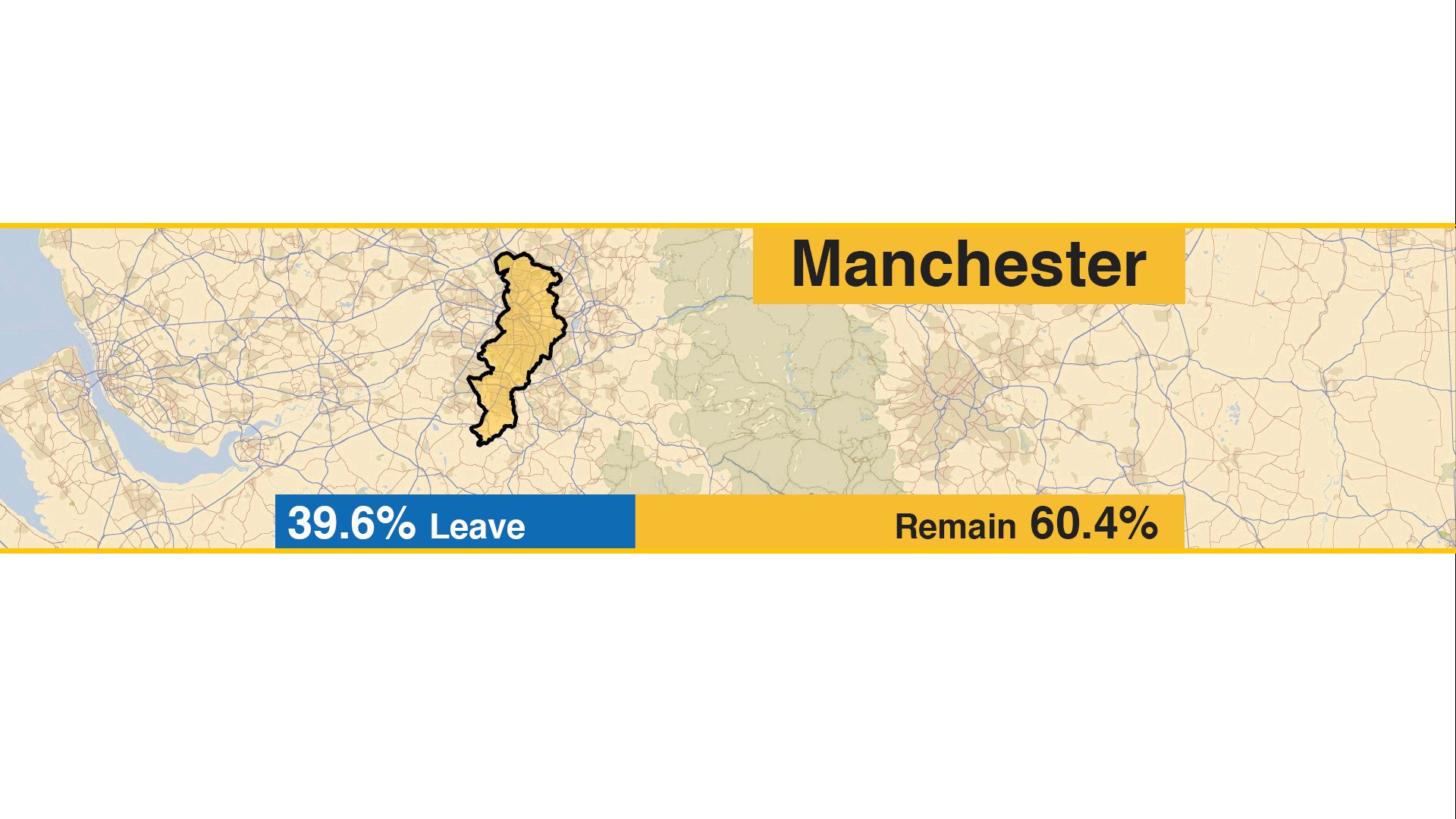

The North West is a Labour stronghold - or, rather, two very distinct Labour strongholds. The first of these is typified perhaps by metropolitan Manchester, which voted 60/40 to remain.

Martin Yuille is an articulate and passionate Labour activist, a retired professor of genetics and every inch the educated liberal metropolitan.

Martin Yuille

He is convinced that there is plenty of evidence which, he says, proves that the “will of the people” as expressed in June 2016 has changed not only across the North West but throughout the country.

“There’s one supremely important issue that needs to be addressed now and that is getting a new public vote,” he says.

“The referendum campaign will not be led by political parties this time,” he insists.

“It’ll be grassroots organisations. That will lead to a different character to the campaign. Mrs May and Jeremy Corbyn will be speaking from the sidelines. It’ll be the genuine voice, the voice of the British people, that will come through. We won’t need Project Fear.”

But head out of the city of Manchester and you don’t need to go far to find the voice of Labour’s other tribe.

In Wigan, which voted 64% to leave, I go to see John Chadwick.

He runs a butcher’s shop and delicatessen, with its own abattoir at the back. The restaurant attached was full almost when I arrived, even though it was barely mid-morning.

He voted to leave and can’t understand why we are still in the EU.

John Chadwick

“If we’re coming out, we don’t want to agree nothing,” he says.

“Why pay £39bn? We went in with nothing, we should come out with nothing. Like a divorce. Just leave. Finish.”

John is 72 and has been working in the family business since he started as an errand boy at the age of 10. He says his business is hampered by EU rules and food regulations that are unnecessary.

“I’ve got to have a vet present when I kill my animals. It costs money. We’re small. I only kill a few. But I have to pay the same [vets] bills as the big abattoirs. How are we supposed to compete?”

I put Martin Yuille’s point to him: that the country didn’t know what kind of Brexit it voted for in 2016, and now that it knows more, should it vote again to make sure the country knows what it’s getting into?

“Oh no, no, no, no,” he says. “We knew what we were getting into. Leave is leave. Nothing else.

“Look. We’re the only country in the world that has ‘Great’ in front of its name. What’s to be frightened of? We proved that a few years ago with BSE and foot and mouth.

“Europe walked away from us then. They didn’t want us. They wouldn’t buy our beef. So what are we worried about? The farmers carried on. The customers still ate meat. It must work in the other industries as well. Honda and Nissan - if they’re leaving the country, don’t buy their cars. No problem.”

Oldham, Greater Manchester

Where does this leave the Labour MPs who form the majority in the North West?

Ros Birch is a Labour activist in Leave-voting Oldham, one of the towns hit hardest by the decline of industry. Oldham is still dominated by the vast red-brick textile mills that once exported across the globe and made this one of the great industrial centres of the North.

But none of the mills spin cotton now. Many have slipped into dereliction. Crumbling brickwork and broken and boarded-up windows are a sorry reminder of a lost greatness.

Ros Birch

Ros is probably a minority voice in Oldham. She wants a second referendum, a People’s Vote, and she thinks Labour MPs should risk angering their Leave-voting constituents to try to make that happen.

“I would say to them that if you know that it [Brexit] is going to be the worst thing that could happen to some of your constituents who are already struggling with low wages and the impact of Universal Credit, depending on food banks, if you know that their lives are not going to be made any better by leaving the EU, then you’ve got to back Remain,” she says.

“And can you understand why many of them feel pulled in two opposing directions?” I ask her.

“I can understand it, but on the other hand I think you’ve got to put your country and your constituents ahead of keeping your job, ahead of getting re-elected. Some of them are definitely frightened of losing their seats.”

The post-industrial heartlands, traditional fortresses of Labour solidarity, are not, in themselves, the problem for the Labour Party - for most continue to return Labour MPs. But they are where Labour’s single biggest challenge begins.

Most Labour members, and most Labour voters, support Remain, and many want the party to back a second referendum. But most Labour MPs sit in seats that voted Leave.

To win an election, the party would have to win over Leave-supporting seats.

Brexit has driven a fracture through both the two big Westminster parties. The divide in the House of Commons might still, formally, be between a Conservative government and a Labour-dominated opposition. But in the country, politics has realigned. The divide out here, beyond the Westminster bubble, is between Remainers and Leavers.

Both main parties are trying to ride two horses that are pulling in opposite directions. Mrs May has spent much of the past two years negotiating not with the European Union, but with her own party.

My next stop was Greater Manchester, where it’s not hard to see that the Labour Party is just as deeply riven.

Modern architecture next to Manchester Opera House

The bus from Stoke-on-Trent to Manchester doesn’t take long. It’s not much more than a hop. But central Manchester feels a world away.

Everywhere you look there is dynamic regeneration. It shines at you in concrete, steel and glass. Here, there is opportunity for an educated workforce.

The North West is a Labour stronghold - or, rather, two very distinct Labour strongholds. The first of these is typified perhaps by metropolitan Manchester, which voted 60/40 to remain.

Martin Yuille is an articulate and passionate Labour activist, a retired professor of genetics and every inch the educated liberal metropolitan.

Martin Yuille

He is convinced that there is plenty of evidence which, he says, proves that the “will of the people” as expressed in June 2016 has changed not only across the North West but throughout the country.

“There’s one supremely important issue that needs to be addressed now and that is getting a new public vote,” he says.

“The referendum campaign will not be led by political parties this time,” he insists.

“It’ll be grassroots organisations. That will lead to a different character to the campaign. Mrs May and Jeremy Corbyn will be speaking from the sidelines. It’ll be the genuine voice, the voice of the British people, that will come through. We won’t need Project Fear.”

But head out of the city of Manchester and you don’t need to go far to find the voice of Labour’s other tribe.

In Wigan, which voted 64% to leave, I go to see John Chadwick. He runs a butcher’s shop and delicatessen, with its own abattoir at the back. The restaurant attached was full almost when I arrived, even though it was barely mid-morning.

He voted to leave and can’t understand why we are still in the EU.

John Chadwick

“If we’re coming out, we don’t want to agree nothing,” he says.

“Why pay £39bn? We went in with nothing, we should come out with nothing. Like a divorce. Just leave. Finish.”

John is 72 and has been working in the family business since he started as an errand boy at the age of 10. He says his business is hampered by EU rules and food regulations that are unnecessary.

“I’ve got to have a vet present when I kill my animals. It costs money. We’re small. I only kill a few. But I have to pay the same [vets] bills as the big abattoirs. How are we supposed to compete?”

I put Martin Yuille’s point to him: that the country didn’t know what kind of Brexit it voted for in 2016, and now that it knows more, should it vote again to make sure the country knows what it’s getting into?

“Oh no, no, no, no,” he says. “We knew what we were getting into. Leave is leave. Nothing else.

“Look. We’re the only country in the world that has ‘Great’ in front of its name. What’s to be frightened of? We proved that a few years ago with BSE and foot and mouth.

“Europe walked away from us then. They didn’t want us. They wouldn’t buy our beef. So what are we worried about? The farmers carried on. The customers still ate meat. It must work in the other industries as well. Honda and Nissan - if they’re leaving the country, don’t buy their cars. No problem.”

Where does this leave the Labour MPs who form the majority in the North West?

Ros Birch is a Labour activist in Leave-voting Oldham, one of the towns hit hardest by the decline of industry. Oldham is still dominated by the vast red-brick textile mills that once exported across the globe and made this one of the great industrial centres of the North.

But none of the mills spin cotton now. Many have slipped into dereliction. Crumbling brickwork and broken and boarded-up windows are a sorry reminder of a lost greatness.

Ros Birch

Ros is probably a minority voice in Oldham. She wants a second referendum, a People’s Vote, and she thinks Labour MPs should risk angering their Leave-voting constituents to try to make that happen.

“I would say to them that if you know that it [Brexit] is going to be the worst thing that could happen to some of your constituents who are already struggling with low wages and the impact of Universal Credit, depending on food banks, if you know that their lives are not going to be made any better by leaving the EU, then you’ve got to back Remain,” she says.

“And can you understand why many of them feel pulled in two opposing directions?” I ask her.

“I can understand it, but on the other hand I think you’ve got to put your country and your constituents ahead of keeping your job, ahead of getting re-elected. Some of them are definitely frightened of losing their seats.”

Heading north again for the last leg of my tour, I thought of those words I’d heard at the start of my trip on Danny Babey’s yacht on Southampton Water: “Why can’t we make our own rules? It’s not easy being told what to do by another country.”

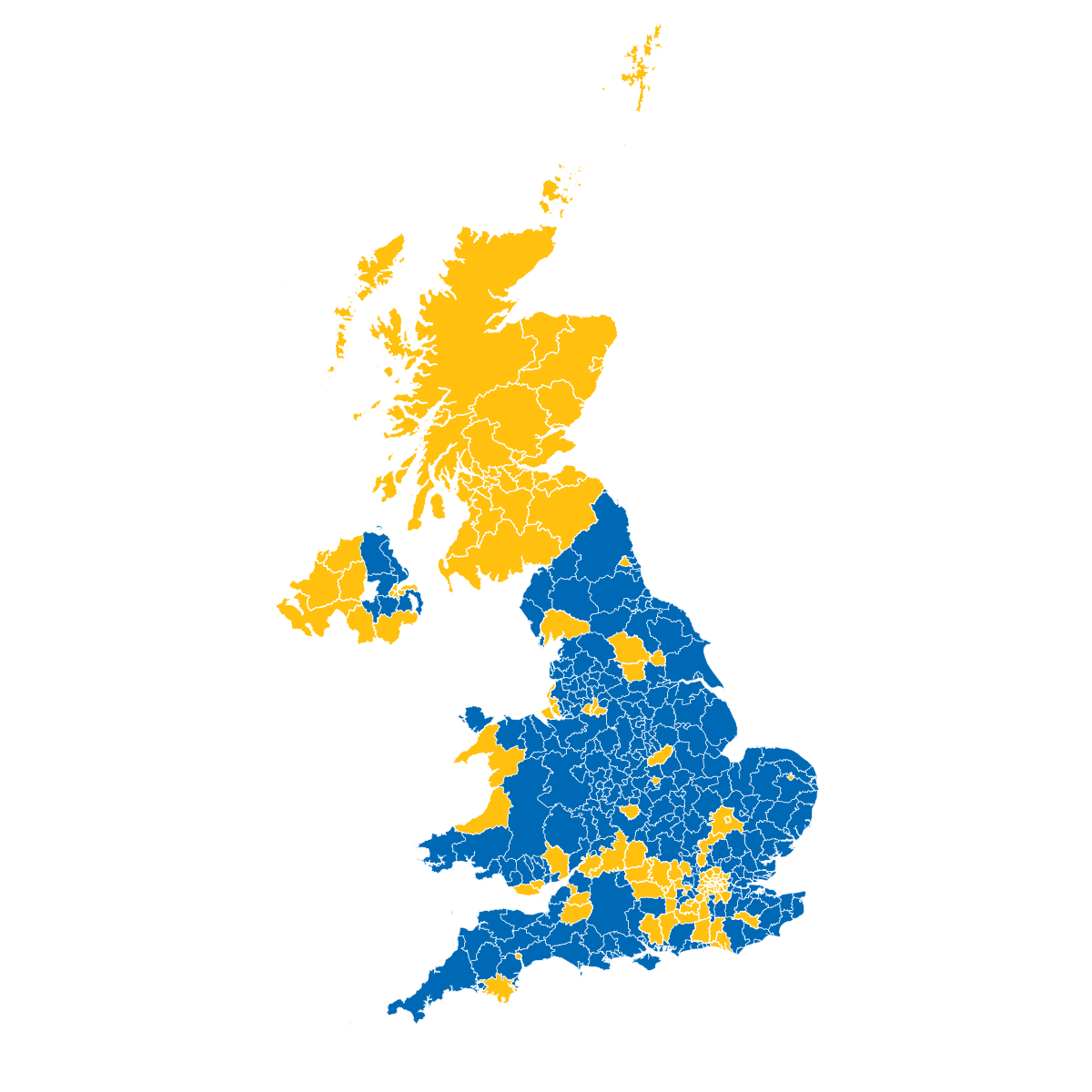

Scotland voted 62% to 38% to remain, but will leave with the rest of the UK all the same.

Not a single one of the country’s 32 local authority areas returned a majority for Leave. Unfurl the results map that shows Leave areas coloured blue and Remain yellow, and the difference is stark.

The border between blue and yellow runs precisely the length of the Anglo-Scottish border - yellow to the north, blue to the south.

I grew up in Scotland, so crossing that border is always a homecoming for me. When I was a child in the 70s, we lived in a constituency that returned an SNP MP to Westminster. Support for independence was far lower then. Scotland felt very British.

When did England and Scotland start to diverge so clearly in the way they vote? And does the divergence represent a divergence in the values that the two nations embrace?

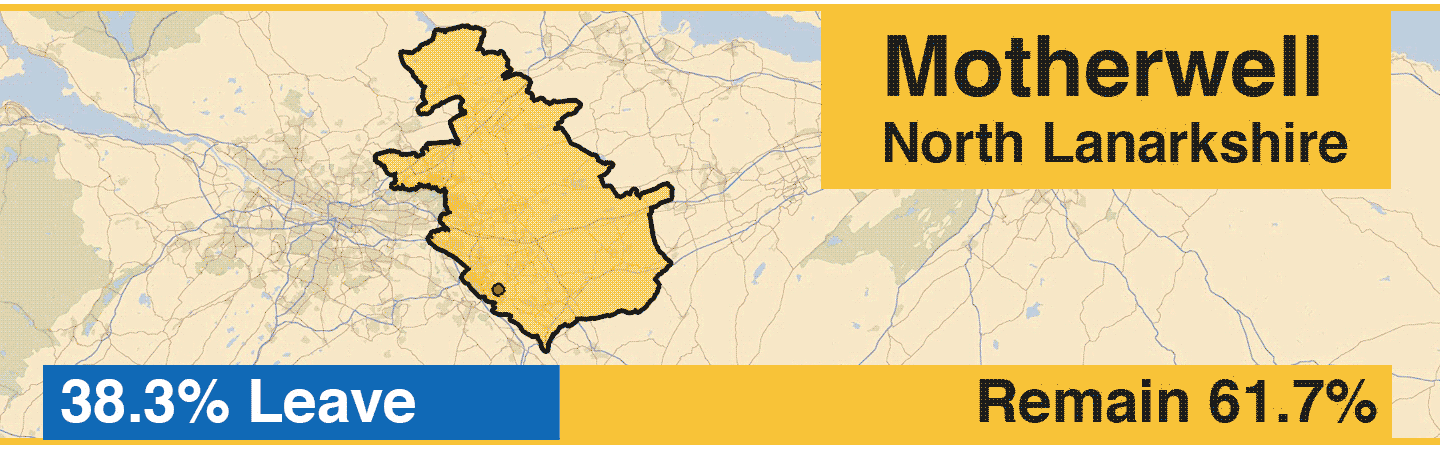

My final destination was Motherwell.

Motherwell, North Lanarkshire

In any other part of the UK except Scotland, Motherwell would probably have voted to leave. Its economy was devastated in the 1990s by the closure of the huge Ravenscraig steelworks.

At its height it was one of the largest steel plants in Western Europe. It employed 13,000 people and sustained the whole town.

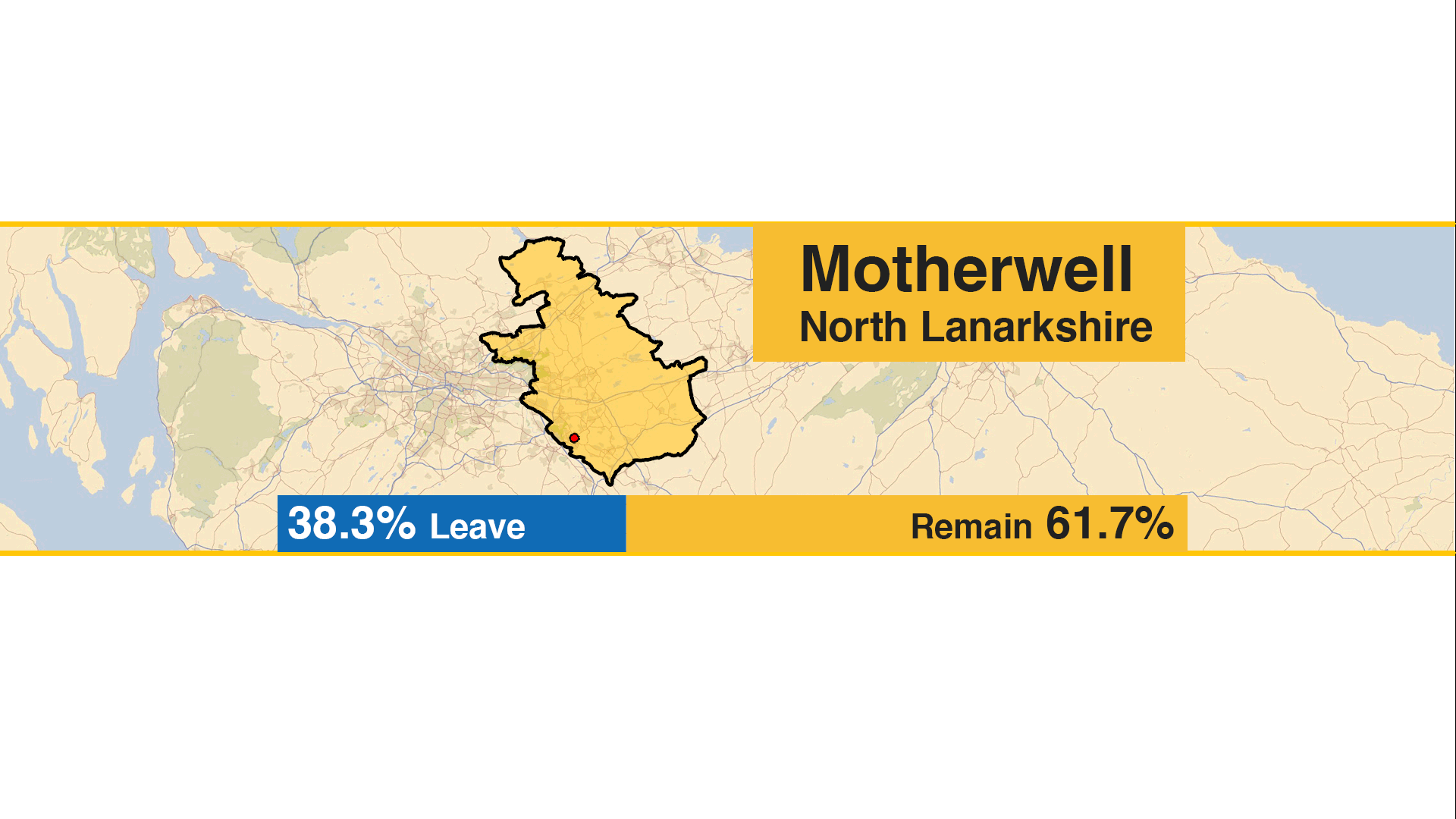

Motherwell has never fully recovered from the decline of steel. It is every bit as “left behind” by globalisation as Stoke-on-Trent. And yet North Lanarkshire, with Motherwell its main town, voted 62% to 38% to remain - about the Scottish average.

The 2014 Independence referendum fundamentally changed politics in Scotland. It realigned political allegiances.

Glasgow, 2014

In the Scotland I grew up in, aside from a surge in support for the SNP in 1974, when the party returned 11 MPs to Westminster, the defining divide was between Labour and Conservative, just as it was elsewhere in the UK.

That Labour-Tory duopoly endured in England. But in Scotland it started to change in the 1980s. In the Thatcher decade, Labour returned stronger and stronger majorities, eventually winning 50 of Scotland’s 72 seats.

The Tories dwindled until, in 1997, they were wiped out completely.

For the next 20 years, the Scottish Conservatives had only one MP in the House of Commons, or none at all. The Conservative Party began to look more and more like a mainstream party in England alone.

But Labour’s socio-economic base - the communities which had grown up around Scotland’s traditional heavy industries - was gradually being eroded.

Shipyard at Greenock, circa 1964

One after another the shipyards, the coal fields, the steelworks closed. Industrial decline was dramatic, rapid and painful. It changed the country’s sense of itself.

It is easy to see now - though it wasn’t so clear then - that those communities were bedrocks not just of Labour solidarity; they were also pillars of British identity in Scotland. If you were a miner in Midlothian, you were bound into a community of shared interest with miners in Yorkshire and South Wales. You worked for the great pan-British enterprise of coal extraction.

The same applied to shipbuilding, and steel and motor manufacturing.

And it all, or almost all, went.

Go to the Ravenscraig site now and you wouldn’t know there had ever been anything industrial there.

Heading north again for the last leg of my tour, I thought of those words I’d heard at the start of my trip on Danny Babey’s yacht on Southampton Water: “Why can’t we make our own rules? It’s not easy being told what to do by another country.”

Scotland voted 62% to 38% to remain, but will leave with the rest of the UK all the same. Not a single one of the country’s 32 local authority areas returned a majority for Leave.

Unfurl the results map that shows Leave areas coloured blue and Remain yellow, and the difference is stark. The border between blue and yellow runs precisely the length of the Anglo-Scottish border - yellow to the north, blue to the south.

I grew up in Scotland, so crossing that border is always a homecoming for me.

When I was a child in the 70s, we lived in a constituency that returned an SNP MP to Westminster. Support for independence was far lower then.

Scotland felt very British.

When did England and Scotland start to diverge so clearly in the way they vote? And does the divergence represent a divergence in the values that the two nations embrace?

My final destination was Motherwell.

In any other part of the UK except Scotland, Motherwell would probably have voted to leave.

Its economy was devastated in the 1990s by the closure of the huge Ravenscraig steelworks. At its height it was one of the largest steel plants in Western Europe. It employed 13,000 people and sustained the whole town.

Motherwell has never fully recovered from the decline of steel. It is every bit as “left behind” by globalisation as Stoke-on-Trent. And yet North Lanarkshire, with Motherwell its main town, voted 62% to 38% to remain - about the Scottish average.

The 2014 Independence referendum fundamentally changed politics in Scotland. It realigned political allegiances.

Glasgow, 2014

In the Scotland I grew up in, aside from a surge in support for the SNP in 1974, when the party returned 11 MPs to Westminster, the defining divide was between Labour and Conservative, just as it was elsewhere in the UK.

That Labour-Tory duopoly endured in England. But in Scotland it started to change in the 1980s. In the Thatcher decade, Labour returned stronger and stronger majorities, eventually winning 50 of Scotland’s 72 seats.

The Tories dwindled until, in 1997, they were wiped out completely. For the next 20 years, the Scottish Conservatives had only one MP in the House of Commons, or none at all. The Conservative Party began to look more and more like a mainstream party in England alone.

But Labour’s socio-economic base - the communities which had grown up around Scotland’s traditional heavy industries - was gradually being eroded.

Shipyard at Greenock, circa 1964

One after another the shipyards, the coal fields, the steelworks closed. Industrial decline was dramatic, rapid and painful. It changed the country’s sense of itself.

It is easy to see now - though it wasn’t so clear then - that those communities were bedrocks not just of Labour solidarity; they were also pillars of British identity in Scotland. If you were a miner in Midlothian, you were bound into a community of shared interest with miners in Yorkshire and South Wales. You worked for the great pan-British enterprise of coal extraction.

The same applied to shipbuilding, and steel and motor manufacturing.

And it all, or almost all, went.

Go to the Ravenscraig site now and you wouldn’t know there had ever been anything industrial there.

It is a vast green emptiness that has only, in the past few years, begun to undergo redevelopment. There is a new college, an impressive indoor sports centre, and the beginnings of new housing.

I met Jim Fraser there, walking his dog Poppy.

Jim Fraser

Jim trained as an engineer at Ravenscraig in the late 60s and worked there until the plant closed in 1992. He was part of a workforce that had overwhelmingly voted Labour for decades.

Jim began to vote SNP in the 1980s. But he was in a minority. It was, for the most part, a lost cause trying to persuade workers who owed secure jobs and good pensions to a state-owned company called British Steel to vote for the break-up of that state.

Jim is a member of the SNP and in 2014 campaigned for independence. Two years later he voted Remain.

“I mean look at it,” he says, with a sweep of the arm around the empty wasteland of the site. “This used to be buildings. Everything here. Steel-making. The closure changed everything in this area. Yes - it changed the way people vote.”

At the 2015 General Election, Labour was almost wiped out in Scotland. After winning every election for nearly half a century the party held on to only one seat - Edinburgh South. The SNP won 56 seats - all but three of Scotland’s total. In North Lanarkshire, a huge Labour majority was overturned by the SNP.

SNP leader Nicola Sturgeon in Motherwell, 2015

How did Labour’s Fortress Scotland fall so dramatically?

The answer lies in the way the 2014 independence referendum changed the question in Scotland. After that long campaign, politics in Scotland no longer revolved principally around the question: “Who do you want to govern?” The question instead is: “What state do you want to be governed in?”

For now, the Union still commands a consistent majority (but a narrow one) in the opinion polls.

Support for independence has held firm in the mid 40s. But how does Brexit change the equation? Does it make independence more or less likely?

Martine Nolan trained as an engineer at Strathclyde University.

She works for a fabrication and construction company with a plant outside Motherwell that employs 120 people.

In the yard are the components of a large steel bridge her company is building for a railway crossing in Lincolnshire. About half of what the company makes is for customers in England and Wales.

She voted to stay in both Unions - the UK in 2014 and the EU two years later.

Martine Nolan

“People are discussing Brexit as an idea,” she says.

“They forget that it’s people’s lives. It’s children with nothing on their plates, families going to bed at night cold because they can’t afford the heating. I saw enough of it after the ‘Craig shut. We’re just starting to recover. I don’t want to see that again.

“Why would we want to put further risk and uncertainty into our lives by coming out of the UK? Do you want to see two, three generations of people here with no work? Because that’s what happened here [when Ravenscraig closed].”

But you can feel a different mood among younger people. I arranged to meet a local band rehearsing at the Motherwell Business Centre.

The Banter Thiefs are four young men who were at school together and who’ve been playing gigs around Scotland and elsewhere in Europe for years. They are all strongly for an independent Scotland - and they all voted Remain.

The Banter Thiefs

“For me the Brexit vote was about immigration,” Derek the bass player tells me.

“Scotland is still a place of low immigration compared to places like London, but I don’t think Scotland scaremongers about immigration in the same way as in other places. We are a welcoming country. Scotland needs immigrants. It’s got an ageing population. We need people to come and work here and study here. We don’t want policies based on fear.”

The others nod their agreement. “I think Brexit strengthens the case for independence. Am I more European or more British? Definitely more European.”

I ask Derek whether he supported a second referendum, a People’s Vote. His answer is more concerned with the precedent it would set for the next independence referendum than it was with overturning Brexit.

“I think supporting a People’s Vote is a mistake for the SNP,” he says.

“It could come back to bite them. If we vote for independence in the future and the negotiations go badly then people might say after six months or two years - we need to vote again. And we could lose it then. I think that’s really detrimental.”

On a building site earlier that day I had fallen into conversation with a tiler, working on a bathroom in a new house. I mentioned that I was going to see the Banter Thiefs. “Oh yeah,” he says. “Very pro-independence.”

Chris Roarty

Chris Roarty is a 23-year-old Labour activist.

“Brexit has reinforced my belief that we should stay here in the UK. It’s a huge wake-up call on the risk and uncertainty of leaving,” he says

Although the SNP campaigned to remain, Chris sees a parallel between its 2014 independence plan, and Brexit.

“I think the Leave campaign and the independence campaign, when they were presented with facts on the economy, just said, ‘Oh that’s scaremongering’. But we’re seeing now that negotiations to leave a union can be really difficult. I don’t think we should be risking that again by breaking away from the UK. We can’t go into the unknown. There’s a huge economic risk. We should be opening doors not closing them.”

Many in the SNP assumed that Brexit would lead to spike in support for independence. It hasn’t happened; at least not yet. Why not?

When you glance at that solid block of Remain yellow on the map of Scotland it’s easy to overlook the fact that a million people in Scotland voted to leave the EU - 38% of those who voted.

Of the 45% who voted for independence, as many as one in three supported leaving the EU. Anecdotally, one senior SNP official I spoke to conceded that while many people had moved from No to Yes on independence, there had been movement in the opposite direction too, among people who voted yes in 2014 but don’t want to be taken back into the EU by a future independent Scotland.

Scottish independence supporter, Glasgow, March 2019

There’s also been a revival of Tory fortunes in Scotland. For a generation, the Conservatives had appeared moribund. But after the election of Ruth Davidson as leader, the party repositioned itself.

At the 2017 election, Conservatives in Scotland took the decision not to campaign on the same message as their counterparts in England. There wasn’t much talk in Scotland of “strong and stable government with Theresa May”.

Instead, Davidson’s party campaigned on opposition to a second independence referendum, which Nicola Sturgeon had said was now inevitable. The Tories therefore offered themselves to the electorate as the party most robustly committed to defending the Union.

It worked. Even North Lanarkshire Council, which includes Motherwell, has Tory councillors.

Their leader is Meghan Gallacher. I ask her, too, whether she thought Brexit made independence more or less likely. She says it wouldn’t have any effect.

Meghan Gallacher

“In terms of the independence question, Brexit doesn't change that. In 2014, the people of Scotland voted No, they voted to reject independence,” she says.

“In 2016, the UK then collectively voted to leave the European Union.

“They are not linked. They are two separate referendums.”

This is difficult terrain for the Tories. This is an echo of the 1980s and 90s, when Scotland returned large Labour majorities at election after election, only to wake the next morning to find that the Conservative Prime Minister in Downing Street was installing a team of Tory ministers to govern Scotland from St Andrew’s House in Edinburgh.

The Conservative Party throughout this period countered the “no mandate” argument by asserting that as a constituent part of the UK, it was right and just that Scotland should be governed according to the democratically expressed wishes of the UK as a whole. It didn’t cut much ice with the public.

Opposition to Westminster’s right to choose Scotland’s government gained popular traction, and by the late 1990s there was overwhelming public support for a devolved Scottish parliament.

I asked Meghan Gallacher whether the Conservatives were in danger of walking that path again - in effect telling the Scottish electorate that it was right that their desire to remain in the EU should be disregarded because the UK as a whole had voted to leave. She said she believed Brexit would do no harm to the Union.

“I don't believe that people went out and voted solely [in the independence referendum of 2014] on the subject of the European Union.

“People went out and rejected independence because they believed in the United Kingdom. They believed in the economic benefits, the social benefits the United Kingdom brings to Scotland.”

But the lesson of the 1980s and 90s is clear: if Scotland has to live with decisions that it rejected at the polls, but which the rest of the UK adopted and subsequently imposed in Scotland, there will be a price to pay.

Rule nothing out. Brexit has taught us that the electorate either dismiss warnings of economic disruption as scaremongering, or decide that they care less about the economic consequences than they do about national sovereignty.

And whether you are for or against Brexit, for or against independence, expect that assertion, the one I first heard on a yacht in Southampton - “It’s not easy being told what to do by another country” - to acquire a new force in Scotland, if in the years of negotiation that lie ahead, the key decisions will be made, and the key deals struck, by a UK government in London.

It is a vast green emptiness that has only, in the past few years, begun to undergo redevelopment. There is a new college, an impressive indoor sports centre, and the beginnings of new housing.

I met Jim Fraser there, walking his dog Poppy.

Jim Fraser

Jim trained as an engineer at Ravenscraig in the late 60s and worked there until the plant closed in 1992. He was part of a workforce that had overwhelmingly voted Labour for decades.

Jim began to vote SNP in the 1980s. But he was in a minority.

It was, for the most part, a lost cause trying to persuade workers who owed secure jobs and good pensions to a state-owned company called British Steel to vote for the break-up of that state.

Jim is a member of the SNP and in 2014 campaigned for independence. Two years later he voted Remain.

“I mean look at it,” he says, with a sweep of the arm around the empty wasteland of the site. “This used to be buildings. Everything here. Steel-making. The closure changed everything in this area. Yes - it changed the way people vote.”

At the 2015 General Election, Labour was almost wiped out in Scotland. After winning every election for nearly half a century the party held on to only one seat - Edinburgh South. The SNP won 56 seats - all but three of Scotland’s total. In North Lanarkshire, a huge Labour majority was overturned by the SNP.

SNP leader Nicola Sturgeon on the campaign trail in Motherwell, 2015

How did Labour’s Fortress Scotland fall so dramatically?

The answer lies in the way the 2014 independence referendum changed the question in Scotland. After that long campaign, politics in Scotland no longer revolved principally around the question: “Who do you want to govern?” The question instead is: “What state do you want to be governed in?”

For now, the Union still commands a consistent majority (but a narrow one) in the opinion polls.

Support for independence has held firm in the mid 40s. But how does Brexit change the equation? Does it make independence more or less likely?

Martine Nolan trained as an engineer at Strathclyde University.

She works for a fabrication and construction company with a plant outside Motherwell that employs 120 people.

In the yard are the components of a large steel bridge her company is building for a railway crossing in Lincolnshire. About half of what the company makes is for customers in England and Wales.

She voted to stay in both Unions - the UK in 2014 and the EU two years later.

Martine Nolan

“People are discussing Brexit as an idea,” she says.

“They forget that it’s people’s lives. It’s children with nothing on their plates, families going to bed at night cold because they can’t afford the heating. I saw enough of it after the ‘Craig shut. We’re just starting to recover. I don’t want to see that again.

“Why would we want to put further risk and uncertainty into our lives by coming out of the UK? Do you want to see two, three generations of people here with no work? Because that’s what happened here [when Ravenscraig closed].”

But you can feel a different mood among younger people. I arranged to meet a local band rehearsing at the Motherwell Business Centre.

The Banter Thiefs are four young men who were at school together and who’ve been playing gigs around Scotland and elsewhere in Europe for years. They are all strongly for an independent Scotland - and they all voted Remain.

The Banter Thiefs

“For me the Brexit vote was about immigration,” Derek the bass player tells me.

“Scotland is still a place of low immigration compared to places like London, but I don’t think Scotland scaremongers about immigration in the same way as in other places. We are a welcoming country. Scotland needs immigrants. It’s got an ageing population. We need people to come and work here and study here. We don’t want policies based on fear.”

The others nod their agreement. “I think Brexit strengthens the case for independence. Am I more European or more British? Definitely more European.”

I ask Derek whether he supported a second referendum, a People’s Vote. His answer is more concerned with the precedent it would set for the next independence referendum than it was with overturning Brexit.

“I think supporting a People’s Vote is a mistake for the SNP,” he says. “It could come back to bite them. If we vote for independence in the future and the negotiations go badly then people might say after six months or two years - we need to vote again. And we could lose it then. I think that’s really detrimental.”

On a building site earlier that day I had fallen into conversation with a tiler, working on a bathroom in a new house. I mentioned that I was going to see the Banter Thiefs. “Oh yeah,” he says. “Very pro-independence.”

Chris Roarty

Chris Roarty is a 23-year-old Labour activist.

“Brexit has reinforced my belief that we should stay here in the UK. It’s a huge wake-up call on the risk and uncertainty of leaving,” he says

Although the SNP campaigned to remain, Chris sees a parallel between its 2014 independence plan, and Brexit.

“I think the Leave campaign and the independence campaign, when they were presented with facts on the economy, just said, ‘Oh that’s scaremongering’. But we’re seeing now that negotiations to leave a union can be really difficult. I don’t think we should be risking that again by breaking away from the UK. We can’t go into the unknown. There’s a huge economic risk. We should be opening doors not closing them.”

Scottish independence supporter, Glasgow, March 2019

Many in the SNP assumed that Brexit would lead to spike in support for independence. It hasn’t happened; at least not yet. Why not?

When you glance at that solid block of Remain yellow on the map of Scotland it’s easy to overlook the fact that a million people in Scotland voted to leave the EU - 38% of those who voted.

Of the 45% who voted for independence, as many as one in three supported leaving the EU. Anecdotally, one senior SNP official I spoke to conceded that while many people had moved from No to Yes on independence, there had been movement in the opposite direction too, among people who voted yes in 2014 but don’t want to be taken back into the EU by a future independent Scotland.

There’s also been a revival of Tory fortunes in Scotland. For a generation, the Conservatives had appeared moribund. But after the election of Ruth Davidson as leader, the party repositioned itself.

At the 2017 election, Conservatives in Scotland took the decision not to campaign on the same message as their counterparts in England. There wasn’t much talk in Scotland of “strong and stable government with Theresa May”.

Instead, Davidson’s party campaigned on opposition to a second independence referendum, which Nicola Sturgeon had said was now inevitable. The Tories therefore offered themselves to the electorate as the party most robustly committed to defending the Union.

It worked. Even North Lanarkshire Council, which includes Motherwell, has Tory councillors.

Their leader is Meghan Gallacher. I ask her, too, whether she thought Brexit made independence more or less likely. She says it wouldn’t have any effect.

Meghan Gallacher

“In terms of the independence question, Brexit doesn't change that. In 2014, the people of Scotland voted No, they voted to reject independence,” she says.

“In 2016, the UK then collectively voted to leave the European Union.

“They are not linked. They are two separate referendums.”

This is difficult terrain for the Tories. This is an echo of the 1980s and 90s, when Scotland returned large Labour majorities at election after election, only to wake the next morning to find that the Conservative Prime Minister in Downing Street was installing a team of Tory ministers to govern Scotland from St Andrew’s House in Edinburgh.

The Conservative Party throughout this period countered the “no mandate” argument by asserting that as a constituent part of the UK, it was right and just that Scotland should be governed according to the democratically expressed wishes of the UK as a whole. It didn’t cut much ice with the public.

Opposition to Westminster’s right to choose Scotland’s government gained popular traction and by the late 1990s there was overwhelming public support for a devolved Scottish parliament.

I asked Meghan Gallacher whether the Conservatives were in danger of walking that path again - in effect telling the Scottish electorate that it was right that their desire to remain in the EU should be disregarded because the UK as a whole had voted to leave. She said she believed Brexit would do no harm to the Union.

“I don't believe that people went out and voted solely [in the independence referendum of 2014] on the subject of the European Union.

“People went out and rejected independence because they believed in the United Kingdom. They believed in the economic benefits, the social benefits the United Kingdom brings to Scotland.”

But the lesson of the 1980s and 90s is clear: if Scotland has to live with decisions that it rejected at the polls, but which the rest of the UK adopted and subsequently imposed in Scotland, there will be a price to pay.

Rule nothing out. Brexit has taught us that the electorate either dismiss warnings of economic disruption as scaremongering, or decide that they care less about the economic consequences than they do about national sovereignty.

And whether you are for or against Brexit, for or against independence, expect that assertion, the one I first heard on a yacht in Southampton - “It’s not easy being told what to do by another country” - to acquire a new force in Scotland, if in the years of negotiation that lie ahead, the key decisions will be made, and the key deals struck, by a UK government in London.

Brexit has divided Britain bitterly. We are going through arguably the most profound re-orientation since World War II.

The referendum posed a binary question to which there were multiple answers. Those who fought the Leave campaign quickly divided, after their victory, on what Leave meant.

Much of the country feels cheated.

Remainers feel cheated because they believe the Leave campaign scraped over the 50% mark by lying about how easy leaving the EU would be, by insisting that Britain would “hold all the cards” and that the UK could have all the benefits of full membership without any of the responsibilities - having its cake and eating it.

And Leavers feel cheated because the result was clear and we still haven’t left. Many believe a “liberal establishment” is sabotaging Brexit, often in secret. There is widespread contempt for MPs and for the institution of parliament. A stab-in-the-back narrative is gaining traction. If Brexit goes wrong, or if it doesn’t happen, there will be a search for scapegoats.

The Leave vote was, in many places, an expression of revolt against a perceived powerlessness - of “not being included in the game called Great Britain” as Danny Flynn in Stoke-on-Trent put it to me. How much more powerless will those communities feel if Brexit, in the end, doesn’t happen?

“We’re the only country in the world with Great in front of its name,” John Chadwick in Wigan said. “What is there to be frightened of?”

We’re also one of the few countries in the world with United in its name. If the last three years have damaged our democracy, they have also raised new and pressing questions about whether the UK will emerge from this process as a single state.

For those of us old enough to remember how the 1980s affected the attitude of Scots toward devolution, the next few years look like fertile territory for the independence movement.

This trip has been a sobering exercise.

Whatever emerges in the years that lie ahead, the UK has some work to do in repairing its democracy, in restoring trust between the institutions of political power and the governed.

For the inescapable conclusion is this: almost three years after voting for the most radical change in the country’s destiny, almost nobody is unequivocally happy. And everybody believes they know who’s to blame. Recrimination hangs in the air.

Don’t we need to have a serious conversation about how that has happened?