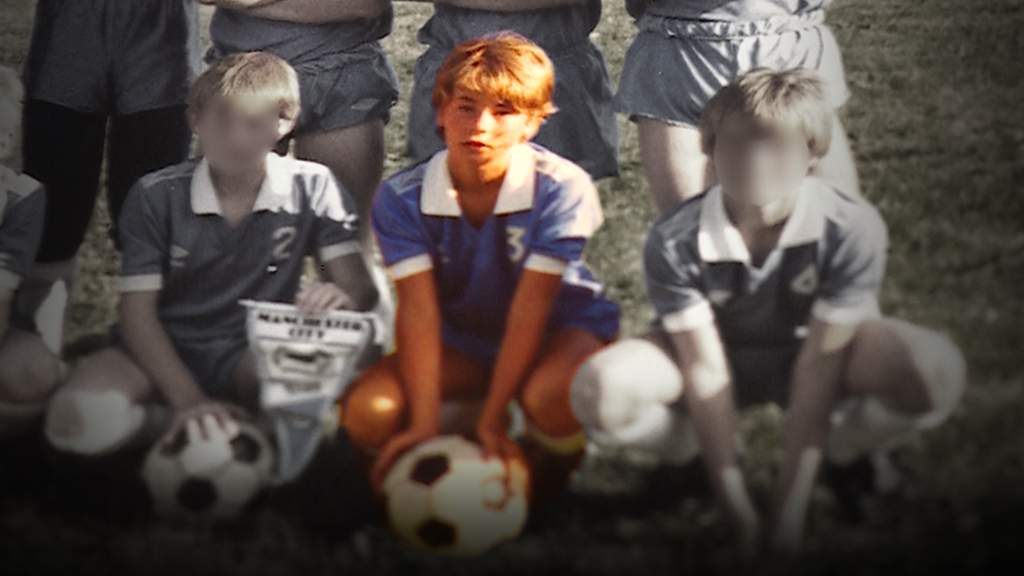

Gary Cliffe was 11 in 1981. He was living south of Manchester and dreaming of FA Cup glory.

Manchester City had reached the cup final at Wembley that season, only losing to Spurs after a replay and one of the FA Cup's iconic moments: Argentine midfielder Ricky Villa dribbling his way brilliantly through the City defence and turning the ball past the goalkeeper.

Cliffe, though, like his father, was always much more of a United fan. His parents encouraged him to play at an early age. They weren’t pushy, just very supportive.

Most weekends were spent jumping into the back of his dad’s battered Chrysler Sunbeam to be dropped off at muddy changing rooms from Nantwich to Crewe.

Gary Cliffe

Every 11-year-old kid at school wanted to play for City or United. Just a lucky few would ever come close.

“Obviously I wanted to make it as a footballer, who wouldn’t?” he told the BBC’s Victoria Derbyshire programme. “That was my dream and I almost got there.”

Like others, many others, Cliffe’s life was changed forever by a coach he once respected and his parents once trusted.

“He was the star-maker, the guy who was going to take me to become a professional footballer,” he says.

My childhood was ruined by this man. He's ruined hundreds of lives. I know because I was there.”

Gary Cliffe talked to Victoria Derbyshire:

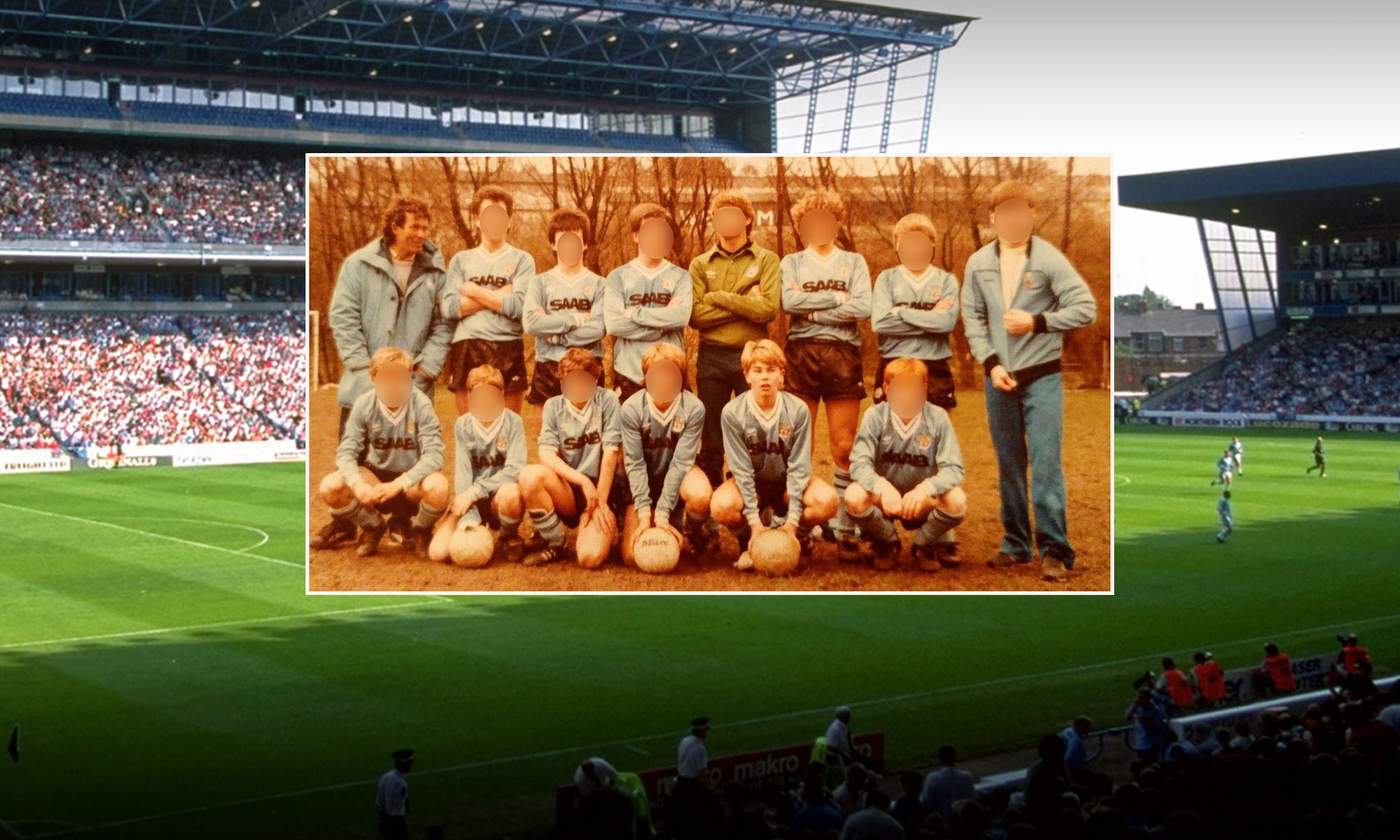

This was the era just before the Premier League. Before live football on TV. Before youth development programmes and academies.

Professional clubs still recruited young players from local feeder teams linked to adult sides but run at arm’s length by amateur coaches.

In this world of dreams and promises one name really stood out.

Barry Bennell had a strong reputation. He was a talented coach with a new way of doing things. He was lively, charismatic and good looking.

He had a back story to impress as well. Bennell had played briefly for Chelsea’s reserve side before brittle bones, supposedly, forced him to quit.

Now he was back where he grew up, running his own chain of video and sports shops in the North West and training youngsters in his spare time.

Gary Cliffe

By the autumn of 1981, he had just taken over the running of Cliffe’s under 12s side, Pegasus FC, one of a number of clubs he managed linked to Manchester City.

Straight away the new coach said he wanted to get to know his young players properly.

In pairs they were invited over to his house on the edge of the Peak District for the weekend.

Kitted out with the latest gadgets it was what one young player described as an Aladdin’s cave for kids.

There were arcade machines, pool tables and an endless supply of free football kit. Bennell had dogs, a wildcat, even a pet monkey.

He would turn off the lights and let 10 and 11-year-old children watch adult-rated horror films borrowed from his own video store downstairs.

The heating would be turned down so some boys would get closer to him as a precursor to more serious abuse.

For Cliffe, there was no build up. No serious attempt to groom him first. It started almost immediately.

The touching quickly moved on to forced oral sex and attempted rape.

Mostly it took place when he was alone in Bennell’s house or in his car. But there were times, many times, when other children were abused while they were in the same room as each other.

“There’d be me on one side, Bennell would be in the middle and the other boy on the other side,” says Gary.

“I would know I was being abused, and it’d be naive of anyone to think that the other boy wasn’t. I know they were. I was there. But I couldn’t say anything.”

From the age of 11 to 15, it happened to Cliffe over and over again. At weekends, at Christmas time, every school holiday. Hundreds of times.

I knew it was wrong but I just didn’t have the stomach or the vocabulary to put my hands up and stop it.”

Gary Cliffe

“It was happening with other boys around. They weren’t saying anything. I didn’t say anything. No parents were saying anything. No officials at the club were saying anything.

“I just didn’t have the words. I was dreaming of being a footballer and the bubble would have burst.”

With his confidence and swagger Bennell could also win over parents.

Some mothers worked for him from time-to-time in his chain of video shops.

Another family invited him around for Christmas dinner because they thought he looked lonely.

In Gary’s words Bennell held adults in “the palm of his hand”. They were “in awe of him, taken in by him”.

As for young children, his favoured boys would be promised a bright future in the game.

If a player resisted or, worse, struck back, they would be humiliated, shunned and dropped from the team.

A captain of one of Bennell’s sides told how, after forcing the coach away one night, he was sidelined and stripped of the captaincy.

A rumour quickly went round that he was stealing money from his teammates. He never played for the club again.

On the pitch there was no doubt Bennell was a gifted football coach, one of the most promising in the North West.

His name quickly became linked to one team: Manchester City.

He was never a full member of staff at the club but it’s thought he was paid expenses and given his own pass to its Platt Lane training ground. His teams all played in Manchester City strips.

“In other words,” claims Cliffe, “He had the run of the place.”

“He was producing the teams who won everything. We were the envy of most boys. We’d come back with a trophy most times,” he says.

Bennell would go on to coach a generation of City stars from David White to Andy Hinchcliffe, as well as former Leeds United midfielder Gary Speed.

White has confirmed he was abused. There is no suggestion Hinchcliffe and Speed were victims.

Gary Speed

His young teams were winners. The most talented players signed schoolboy forms, the first step towards a career in the professional game.

But for those looking closely enough, the warning signs were already there.

There were fights with other managers in the youth leagues. Bennell was attacked with a metal peg used to tie down goal nets, leaving him with a deep cut below his eye socket.

The parents of one boy complained to Manchester City after their son was kept up late in a hotel room on an away trip.

Other members of the playing staff were becoming more suspicious about his behaviour.

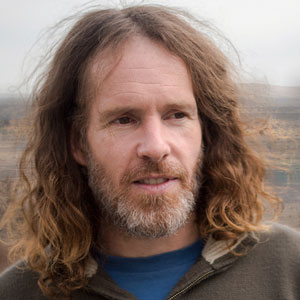

Former goalkeeper and youth team manager Steve Fleet said he first heard rumours in the late 70s.

Steve Fleet

At one point Fleet says, he was under pressure from a club official to give Bennell a proper role, to make him an official part of the City line-up.

I said it was either him or me. I wasn’t working with a person like that. I’d heard he was doing things with kids that weren’t normal.”

On that occasion, he says, he won the argument.

After Fleet left the club in 1980, it appears Bennell became more involved, though he never did make it onto the full coaching staff there.

His victims from that time, and to date seven have come forward publicly, are convinced more could and should have been done.

“They let us down, they didn’t challenge him,” says Cliffe.

“They knew what he was and they allowed it to continue because he was producing results.”

Other young players abused around that time speak of the same culture of wilful ignorance and neglect.

Interviewed by Channel 4 back in 1997, Manchester City officials said they didn’t receive a single formal complaint about Bennell’s behaviour.

There was “no evidence whatsoever from that side of the fence”, claimed former chief scout, the late Ken Barnes.

Manchester City is now in the middle of its own internal review led by the QC Jane Mulcahy.

It will examine if more should have been done to protect young players in the past and look at the club’s current child protection policies.

In a statement, the club said: “Manchester City offers its heartfelt sympathy to all victims for the unimaginably traumatic experiences they have endured.”

“All victims were entitled to expect full protection.”

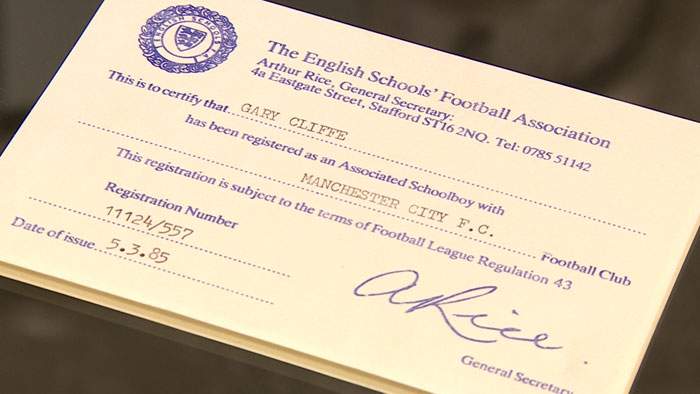

On 30 November 1984 in a short ceremony at Platt Lane, Cliffe finally signed associated schoolboy forms with Manchester City.

It was an important milestone. Only the most talented youngsters made it so far.

Bennell was alongside him in that room at that moment. There was once a photograph to prove it. His mother found it years later and cut the coach out of the frame.

By then aged 14, Cliffe started training with the youth side and was stopped from playing for any other team.

But even though he was moving on he could not escape Bennell’s influence and the stigma that went with it.

He says he was bullied for his close association with the coach, who was, according to other staff members, by then the subject of raised eyebrows and knowing looks at the club.

Cliffe says another coach, again not directly employed by Manchester City, would often laugh about it, calling him Bennell’s “bum boy” in front of his teenage teammates.

He says that finished him off.

“He used those words and the other boys didn’t say anything but they knew,” says Cliffe.

“Not only had I had it physically off Bennell but now this other coach who was supposed to take me through to 16 - the crucial time when you get signed on.

“He had the audacity to say those words and take the Mick. It was horrific.”

Aged 16, Cliffe quit the game. He eventually became a detective with Cheshire Police.

Gary Cliffe

As for Barry Bennell, his time with Manchester City ended abruptly in 1984. No-one is quite sure why but it’s thought he was, once again, turned down for a full-time coaching position.

With his options limited, his attention simply switched from one club in North West England to another.

Just an hour’s drive south of Manchester is the old railway town of Crewe. In the world of football the two places could not be much further apart.

In 1984 Crewe Alexandra were struggling in the old fourth division, the lowest tier in the football league.

The club had just appointed a promising young manager, Dario Gradi, who knew Barry Bennell from his time as a coach at Chelsea.

His old contact was brought in to help modernise the youth set up.

Over the next decade Crewe consistently produced young players who would later be sold on for good money to top flight clubs. Its academy became one of the most respected in the game.

England internationals Rob Jones, Danny Murphy and Seth Johnson all came through there.

David Platt joined as a 19-year-old and left three years later to become one of the country’s brightest stars.

Its youth system was so successful it was soon known by a different name: The Football Factory.

After years of trying, Barry Bennell was finally on a professional club’s payroll, officially responsible for development and scouting.

One of the first players he spotted was a promising 11-year-old playing for Stockport Boys. His name was Andy Woodward.

Andy Woodward

The pattern of abuse was horribly familiar.

“Within about three or four weeks he asked my parents if I could go and stay at his address. It started there,” Woodward says.

Initially it was sexual touching but then it got worse. He raped me. I don’t want to put a number on how many times, but it was over a four-year period.”

Like other victims, Woodward, an outgoing young boy, quickly became introverted and withdrawn.

Bennell appeared to target the quieter, more thoughtful players, threatening to rip up their dreams if they ever stepped out of line or spoke up.

“It was that control,” says Woodward. “All I wanted to do was be a footballer. But he threatened to take that away from me.”

“I was crying out for somebody at the club, at Crewe, to say it’s wrong. But that didn’t happen.”

Andy Woodward

Woodward was far from the only victim linked to Crewe Alexandra. To date another five players have come forward, in public, to say they were abused in the same way.

Bennell’s crimes took place not just at his house in Cheshire.

A court later heard it also happened on one of Crewe’s training pitches and at the home of manager Gradi, himself, though he knew nothing about it.

Again with Crewe’s football factory churning out so much talent, it appears few wanted to ask too many questions about Bennell’s treatment of the children in his care.

At one point Bennell became so important to the club’s success, that one source says Gradi asked to split his share of sell-on fees with his youth coach.

Gradi, by then a club director, had struck a deal with the board to receive 10 percent of any payment if one of the team’s young players was sold to another side.

He asked the board for this to be cut to seven percent, with the other three percent passed directly to Bennell, according to the club’s former managing director.

Just an hour’s drive south of Manchester is the old railway town of Crewe. In the world of football the two places could not be much further apart.

In 1984 Crewe Alexandra were struggling in the old fourth division, the lowest tier in the football league.

The club had just appointed a promising young manager, Dario Gradi, who knew Barry Bennell from his time as a coach at Chelsea.

His old contact was brought in to help modernise the youth set up.

Over the next decade Crewe consistently produced young players who would later be sold on for good money to top flight clubs. Its academy became one of the most respected in the game.

England internationals Rob Jones, Danny Murphy and Seth Johnson all came through there.

David Platt joined as a 19-year-old and left three years later to become one of the country’s brightest stars.

Its youth system was so successful it was soon known by a different name: The Football Factory.

After years of trying, Barry Bennell was finally on a professional club’s payroll, officially responsible for development and scouting.

One of the first players he spotted was a promising 11-year-old playing for Stockport Boys. His name was Andy Woodward.

Andy Woodward

The pattern of abuse was horribly familiar.

“Within about three or four weeks he asked my parents if I could go and stay at his address. It started there,” Woodward says.

Initially it was sexual touching but then it got worse. He raped me. I don’t want to put a number on how many times, but it was over a four-year period.”

Like other victims, Woodward, an outgoing young boy, quickly became introverted and withdrawn.

Bennell appeared to target the quieter, more thoughtful players, threatening to rip up their dreams if they ever stepped out of line or spoke up.

“It was that control,” says Woodward. “All I wanted to do was be a footballer. But he threatened to take that away from me.”

“I was crying out for somebody at the club, at Crewe, to say it’s wrong. But that didn’t happen.”

Andy Woodward

Woodward was far from the only victim linked to Crewe Alexandra. To date another five players have come forward, in public, to say they were abused in the same way.

Bennell’s crimes took place not just at his house in Cheshire.

A court later heard it also happened on one of Crewe’s training pitches and at the home of manager Gradi, himself, though he knew nothing about it.

Again with Crewe’s football factory churning out so much talent, it appears few wanted to ask too many questions about Bennell’s treatment of the children in his care.

At one point Bennell became so important to the club’s success, that one source says Gradi asked to split his share of sell-on fees with his youth coach.

Gradi, by then a club director, had struck a deal with the board to receive 10 per cent of any payment if one of the team’s young players was sold to another side.

He asked the board for this to be cut to seven per cent, with the other three per cent passed directly to Bennell, according to the club’s former managing director.

Throughout the 1980s, there is no evidence that a single complaint was ever made to either the police or Crewe Alexandra itself.

Again, though, there were plenty of rumours about Bennell’s behaviour.

A senior member of the backroom staff at Crewe was said to have refused to allow their own children to be trained by the coach.

There was talk that Sir Alex Ferguson personally asked security guards to escort Bennell off Manchester United’s training ground at Littleton Road. Sir Alex says he cannot recall the incident happening.

The mother of a young Crewe player said she sent an anonymous letter to Gradi, when he was manager, to complain about boys sharing hotel beds with Bennell on away trips.

No allegation of sexual abuse was made at the time and it’s not clear if the letter, which she remembers writing in 1989 or 1990, was ever opened by Gradi or Crewe.

Perhaps the strongest warning, though, is said to have come from one of the most senior officials at the club, former managing director Hamilton Smith.

Hamilton Smith

After hearing rumours of inappropriate behaviour and a second-hand allegation of abuse from an anonymous parent, he says he changed the agenda of a board meeting to deal directly with concerns about the youth coach.

“I thought no this is no good. I’ve had it right up to here. It’s got to stop,” he said.

“I got back home and I rang the then vice-chairman John Bowler and told him what had happened,” said Smith.

“I said, ‘This is hot. We’ve got to address it.’”

During the board meeting, held at the house of then-chairman Norman Rowlinson, a senior police source was called who suggested Bennell should be moved on.

By this time though Barry Bennell was a full-time employee at Crewe and there was no direct complaint from a parent.

Instead Smith says the club directors present decided John Bowler, now Crewe Alexandra’s chairman, should raise only more general concerns with manager Dario Gradi about Barry Bennell letting children stay overnight in his house.

Smith described Mr Gradi’s response as “very angry”. At a follow-up meeting the manager made it clear he did not have a problem with Bennell and the coach was allowed to continue working at Crewe Alexandra.

“It makes me furious when [Crewe Alexandra FC] say they didn’t know something was going on,” says Hamilton Smith.

“Everybody involved could and should have done a lot more.”

Dario Gradi

In a 1997 interview Dario Gradi said the club had no cause for any concern when Bennell was working at Crewe.

He later said the first he or anyone else at the club knew of any crimes was when Bennell was finally arrested in 1994.

Now Crewe’s director of football, Gradi has had his coaching licence suspended by the Football Association while it carries out a wider inquiry into abuse allegations and how they’ve been handled across football.

In a statement following the guilty verdicts against Bennell, Crewe Alexandra FC expressed its deepest sympathies for his victims - and reiterated that it had not been aware of any sexual abuse by him, either before or during his time with the club.

The club also stressed “it would have contacted the police immediately” if it had any suspicion that Bennell was committing acts of abuse, “either before, during or after he left the club’s employment”.

Cheshire police say that during the course of their inquiry Crewe Alexandra, Manchester City and the FA were “nothing but cooperative”.

They say they could find no evidence of a conspiracy to cover up allegations of abuse.

Andy Woodward worked through the ranks at Crewe Alexandra, making his first-team debut in 1992 at the age of 19.

Three years later he signed for Bury, playing 24 times in his first full season as the Lancashire club won the division two title.

Then out of nowhere he was shopping at Tesco’s one Sunday night, when he broke down, almost collapsed and was taken to hospital.

“I went through the door and all of a sudden this rush of adrenaline went through my body,” he says.

“I wouldn’t wish that feeling on anyone. It was the scariest thing that had happened in my life.”

He started to suffer from repeated panic attacks while playing, covering them up by claiming he was injured - inventing a twisted ankle or problem hamstring.

Andy Woodward

His career faded out, ending at the age of 29 after short spells with Sheffield United, Scunthorpe and Halifax.

“In my head there were all sorts of things going on. I don’t know how I even played,” he says.

“I can’t put into words what was done to me. But I think other people out there will understand. I think we survive and that’s it. We just survive.”

As with Manchester City, the reasons why Bennell finally left Crewe Alexandra are unclear. People say he was sacked quietly in 1991 after a dispute over tactics.

He was soon back coaching at a small local team in the Cheshire area, Stone Dominoes, where he took young boys overseas to training camps in Jacksonville, Florida.

It was there in the summer of 1992 that his long history of abuse finally caught up with him.

Bennell sexually assaulted a 13-year-old British boy in a hotel room.

Only this time the child, who has never been named, told his parents partly because he said he was terrified of catching Aids.

Bennell was arrested by police in the US and eventually pleaded guilty to five counts of sexual battery of a child. He spent three years in an American prison.

The US authorities suspected this wasn’t the first time he had abused young boys.

Libby Senterfitt from the State Attorney’s office in Florida wrote a strong warning letter to Fifa’s head office in Switzerland and to the Football Association.

Cheshire Police was alerted and started investigating possible crimes in the UK.

With Bennell serving time in prison, the subject was tackled by the national media for the first time.

In January 1997 investigative journalist Deborah Davis presented Soccer’s Foul Play, an hour-long documentary for Channel 4.

It named Bennell and other alleged abusers in the game, giving a voice to victims for the first time and asking tough questions of club officials.

But the Football Association reacted defensively and the response from the rest of the media was muted.

One television critic dismissed the programme as alarmist, savaging it for “charging around, looking for somewhere to bang in its nails”.

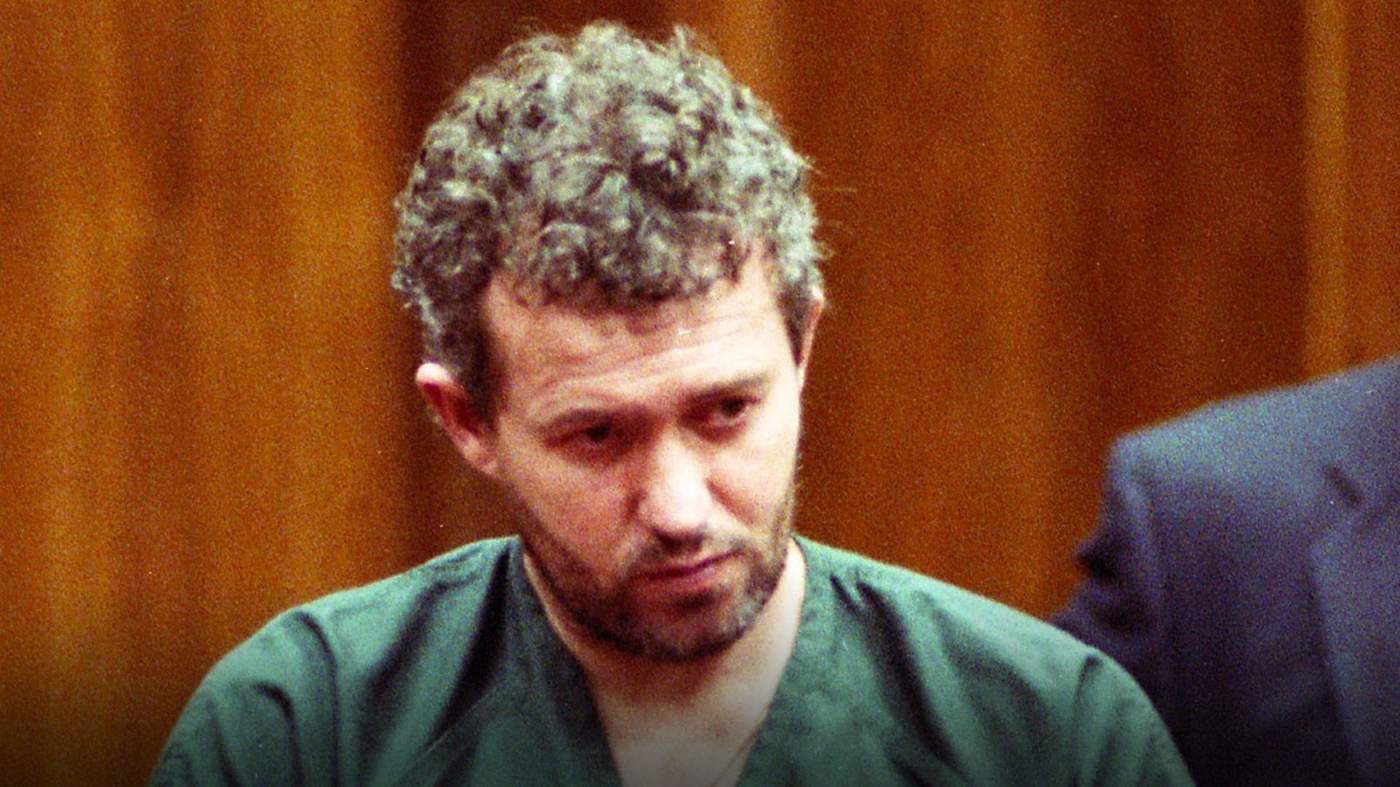

A year later, in 1998, Bennell was deported from the US and flown back to the UK.

Barry Bennell

He was arrested as he landed and later admitted 23 charges of sexual abuse against six British boys aged nine to 15, changing his plea to guilty just a day before trial.

One of those boys was Andy Woodward.

“When he was jailed I just felt safe he was in prison,” he says.

“His sentence was nine years. Looking back now, nine years for just what happened to me was not enough.”

“I can’t put into words what it has done to me. The impact it had on my life was just catastrophic.”

After Bennell’s release he was convicted once again for historical offences against yet another schoolboy back in the late 1970s. At trial his own barrister described him as a monster.

But all this news was covered only briefly in a handful of local press articles.

There was no huge scandal, no major police investigation, certainly no FA inquiry or soul searching from the clubs involved.

That took another decade.

In November 2016 Woodward made the decision to speak publicly about the abuse and the impact on his life.

He told his story to the Guardian newspaper and the BBC’s Victoria Derbyshire Programme.

His testimony, sitting first on his own, then alongside a group of other survivors on national television, started something unexpected as victim after victim came forward.

At the last count police forces across the country had identified 294 alleged suspects in cases involving 839 possible victims linked to football.

Steve Walters talked to Victoria Derbyshire:

The chairman of the FA, Greg Clarke, has called it the biggest scandal facing the game.

Gary Cliffe was at work that day, checking Twitter on his phone as Andy Woodward sat in a TV studio in London alongside Steve Walters, Jason Dunford and Chris Unsworth.

All four footballers were victims of Bennell, though Jason Dunford had fought him off and wasn’t sexually abused.

As the updates came in, Cliffe decided he couldn’t concentrate on work. He got in his car, pulled over and watched the interview back on his phone sitting at the side of the road.

“They all spoke with such dignity,” he says. “Reassurance is the wrong word but you got the idea that others are there with you and you take comfort from that. That’s what I felt.”

But Cliffe couldn’t add his voice publicly at the time.

By coincidence months earlier he had already contacted the police about Bennell and wanted to press charges.

Barry Bennell

An investigation had started and he had been asked not to speak out in the media while detectives were working on the case.

This wasn’t the first time Cliffe had been in contact with the authorities.

He gave a police statement in 1995 when Bennell was eventually convicted on other charges. At the same time he told his parents what had happened.

Back then though he didn’t feel strong enough to take the case to court, with the possibility he might have to give evidence in front of his abuser.

Now, in his mid-40s, his feelings had changed.

“You get to the stage where you get older and you think, do you know what, I don’t want to have any regrets,” he says.

“So I picked up that phone and made that call.”

Barry Bennell

So did others. After Woodward spoke out more players came forward with their accounts of what happened decades ago.

Bennell was charged with another 55 counts of sexual abuse - which took place between 1979 and 1991.

On 15 February 2018, after a six-week long trial at Liverpool Crown Court, he was convicted once again.

He was found guilty of 43 counts of child sex abuse against another 11 boys.

“My childhood was wrecked. He’s damaged me, there’s no doubt about it. I’ve been on medication for many years now, probably will be for the rest of my life,” says Cliffe.