It’s hard to keep up with Nigel Cropp as he races past suitcases, pet supplies and piggy banks. He found a wife in Yiwu market and now he’s looking for something else. Fidget spinners.

“I buy them for 60 or 70 cents and sell them on for a fiver (£5). At one point I heard they were retailing at $15 (£12). The customers are really fighting for them. I can sell 100,000 a day, maybe 10 million by the end of the year.”

The fidget spinner is this year’s must-have item for schoolchildren in Europe and North America. And Nigel’s current obsession.

Nigel doesn’t usually like shopping but he loves it here. The biggest small goods market in the world is an assault on the senses with the clattering of trolleys, the chattering of traders from every continent and the sweet smell of pineapple from the hawker’s cart.

He claims he could navigate this market blindfold.

The buzz, the energy! You never know who you're going to meet and what you're going to see. It's all about catching a wave, and riding that wave as long as possible.”

The wave was once slower. For hundreds of years, tea, silk and ceramics were the staples on the old Silk Road – an ancient network of trade routes from China to the Middle East and Europe. But in 2017, there’s not much China doesn’t sell to the world and this market is on fast-forward.

Nigel arrived here from the UK 12 years ago, to teach English to factory managers. Soon he realised his students had something to teach him, and he started picking up some business skills.

When he met his wife in a market booth, where she was selling bags, Yiwu became home.

Nigel is speed-walking and talking but his eyes are feverishly scanning side to side… catapults, sewing machines, bicycle pumps and paint rollers. He can’t afford to miss the next new trend or latest colour. It’s a binary world: grab or ignore.

Only seven days from design to delivery. That’s the fastest product turnaround in the world. But there’s no loyalty. Contracts don’t work here! You can turn up with a truck and find your shipment has gone. Someone else came in with two cents more.”

An entire section of the market is filled with toy shops. Nigel says no to the remote-controlled plastic bear careening between our legs on a skateboard.

“Avoid electricals. They won’t pass EU regulations.”

And it’s another no to a soft bear with button eyes.

“Small parts…might choke small children.”

From toys to gift bags. Nigel is now haggling over fractions of a cent on 7,000 matching sets of gift bags in different sizes.

He stabs numbers into a calculator and passes it to the saleswoman.

No-one here gets more than a crumb of the cake. But it’s a very big cake.”

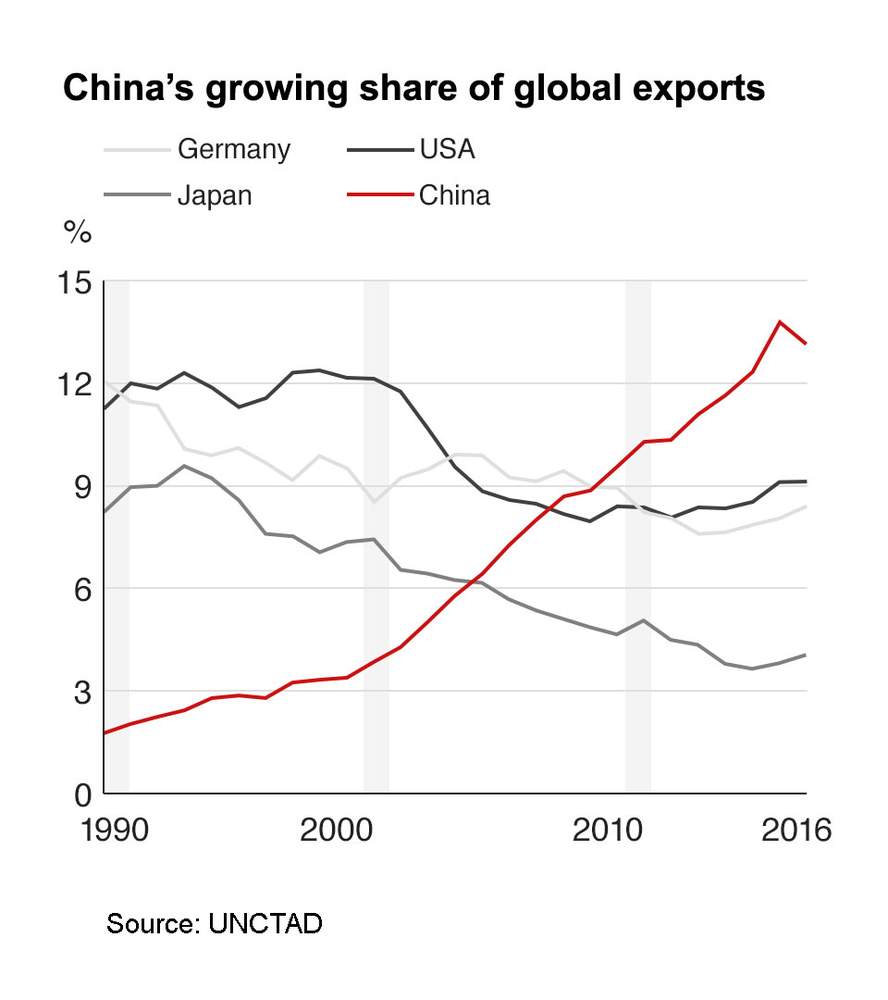

The growth of this cake has made China a trading superpower.

Nigel says the roads and rail lines planned for the new Silk Road will mean even more Yiwu goods heading west. But despite China’s promise that it will be a win-win scenario for China its trading partners, he’s less optimistic about goods travelling back into China. Customs red tape still makes importing a nightmare, he says.

“The government can change the law any time, so there's no real concrete law,” he adds.

But Nigel is pragmatic. He’s a trader after all, and it’s not his problem whether all win equally on China’s new Silk Road. Soon he’s back to hunting for the best fidget spinner.

“When I sleep I dream of spinners. And then a customer phones from the other side of the world, waking me up and begging for more.”

Wu Xiaodong remembers the day he joined the railway. It was 1983. China had a mere 1% of world trade and, aged 17, his own ambitions went no further than a free uniform and a free train ride.

“Our trains were like tractors. We were running a steam railway.”

Now China is the world’s number one trading nation and he’s proud to be a foot soldier on President Xi Jinping’s new Silk Road.

He paces the Yiwu cargo yard in blue uniform and hard hat, barking orders at men with grappling hooks as they ease 40ft shipping containers on to freight carriages. The frenzied din of cranes, sirens, trucks and screeching metal can’t alter the fact that this train for Europe is late.

When Wu Xiaodong joined the railway, Yiwu was a shabby backwater. No-one dreamed of foreign trade back then, he says. Even sending freight across China took two months of planning. Now he’s in charge of sending trains off on a journey that crosses nine countries and more than 7,000 miles. But he's constantly being pushed to make further improvements.

“I’ve done almost every job on the railway - there’s not enough sleep in any of them. Security, logistics, co-ordination, repairs... We’re under a lot of pressure. We need the train to develop faster and better.”

The pressure is coming from the top. Chinese emperors once claimed to rule all under heaven. With the US retreating from global leadership on free trade, President Xi has seized his chance.

His plan is so big that it may be decades before we can say whether it’s a worthy successor of the ancient Silk Road. But with no other country offering a big idea right now, this is the most ambitious bid to shape our century.

Critics say dragging 50 containers from Yiwu to Europe by train is a poor way to start, observing that rail makes little economic sense when you can easily shift 10,000 containers on a single ship. Even with government subsidies the train costs more than twice as much as sea freight, and is slowed by changes of railway gauge and engine.

But Wu Xiaodong points out that rail takes only 18 days, compared to 35 by sea.

“The train can’t take the place of sea freight, but there’s lots of room for expansion, especially to landlocked countries.”

Beijing’s vision is about much, much more than a railway. It’s about roads, pipelines, ports, industrial zones and shipping routes. China is promising to spend almost $1trn on infrastructure to boost trade.

But as it crosses two continents laden with Chinese goods, the freight train has become an important symbol of success.

With all 50 containers loaded, the cargo yard falls still, all now awaiting the engine that will pull this train west. The quiet brings a dragonfly to drink from a puddle. Wu Xiaodong lights a cigarette and glances out along the tracks.

Some day I’m going to make this journey to see it all for myself...”

“Never bring shame on this family.”

A father’s parting words to a daughter. He had wanted Buhalima to train as a doctor. But aged 14 she had other plans. And seven years after leaving the family farm, she is now a lead dancer at the Xinjiang Grand Theatre.

I never did bring shame on him. I’m performing on a world-class stage, using my talent and dancing my heart out. I think I’ve done well.”

We’re talking backstage in Urumqi, capital of the north-western region of Xinjiang. At 21, Buhalima is among 200 performers putting the finishing touches to a spectacular show about the ancient Silk Road. The rehearsal is a scene of organised mayhem with shrieks from a frustrated choreographer, sudden bursts of purple light and thundering music, girls in leggings running to and fro, and camels chewing patiently in the wings.

The story may be old, but this grand re-telling is a modern mission. The show is inspired by the president’s new vision of intercontinental trade - and harking back to the Silk Road is a way to calm the fears of neighbours. India and Japan see a plan to embed Chinese money and muscle across three continents, to take control of strategic ports and amass geopolitical influence. So when China uses the phrase “Silk Road” it is a subtle reminder of traders who came not with gunboats at their back but with laden camel trains.

But the show also claims to display Xinjiang’s “ethnic harmony and economic development” - important buzzwords, as one purpose of the new Silk Road is to tackle China’s security problems, by boosting growth in a region troubled by ethnic and religious tension.

Buhalima is a Muslim from the Uighur ethnic minority. In many ways, Uighurs are closer to the people of Central Asia than to China’s majority population, the Han Chinese. Now outnumbered in Xinjiang, some Uighurs feel marginalised, and the past decade has seen a series of bomb and knife attacks against targets associated with the Chinese state, or against Han civilians.

As Buhalima plaits her long hair and applies her stage makeup, she complains that many Chinese people are now suspicious of Uighurs.

“We are misunderstood. Outsiders pin the blame on all of us. That breaks my heart. One day the bad guys who create the trouble will pay for what they’ve done.”

At the theatre entrance, performers, staff and audiences alike must submit to bag X-rays and body searches.

But to make it easier for visitors to come to Xinjiang – and to other landlocked western regions that have been left behind in China’s boom years - Beijing has invested in new airports, roads and railways. High-speed trains now race west against a backdrop of mountain, desert and sky, broken by the occasional wind farm, yak herd or road crew in straw hats and clouds of dust.

China is counting on the Silk Road to become a magnet for the domestic travel industry. Already tour groups under numbered signs and matching sunhats have transformed the fortunes of oasis towns, such as Dunhuang. The operation there is now epic in scale, with competing loudspeakers thronging the air and the overwhelming smell of a packed camel enclosure. From sunrise to sunset, processions of the long-suffering animals plod the curve of the dune as every rider frames the perfect selfie.

But this tourist army has not yet reached the Xinjiang Grand Theatre. As the house lights go down on the Silk Road show, at least half of its 2,000 seats are empty.

Amid drums and lutes, the story unfolds… a dizzying dance of merchants, monks and maidens in flower-decked meadows. There are special effects, acrobatics and live eagles flying overhead, but some in the audience talk throughout and get up to leave before the performers have taken their bow.

Outside the theatre afterwards, Buhalima is hobbling to hospital, her ankle just the latest in a series of nagging injuries. Away from the stage spectacular, she cuts a lonely figure.

Her parents are far away and she has no plans for a husband despite their heavy hints. She’s even more determined to pursue her career - the girl who goes her own way without bringing shame on her family.

I am a young person in the 21st Century and I have my own way of pursuing my dreams.”

“The thing I fear most is the frozen ground.”

A fierce sun burns into his red hard hat and beads the sweat on his brow. Pinhead flies have gathered on his once spotless white shirt. But Xu Xiwen’s mind is elsewhere. He’s worrying about winter.

“The temperature here sinks to -40C and the wind is death. For four months there’ll be no work on site.”

Xu Xiwen is is an engineer for the Beijing Urban Construction Group and he has just embarked on building 13 stations of an urban light railway in Kazakhstan’s capital, Astana.

The building season is short and his deadline only two years away, but there’s not much to see yet at station number six. A few dozen workers are beginning on foundations with machinery newly arrived from China.

I’m under pressure but I’m staying calm, because losing my head won’t solve anything.”

Xu Xiwen is a veteran of projects abroad, having helped his company build a hospital in Africa, an airport runway in the Maldives and a police school in Costa Rica. But this time he’s in charge.

“I’m very proud. It’s such a big project and I’m leading the team.”

It’s not just his own reputation on the line. This is a first for China too, a chance to export Chinese standards in an industry it would like to command. President Xi was present at the signing ceremony. No wonder Xu Xiwen feels a nation’s expectations upon his shoulders.

“This is Chinese hi-tech engineering, and it’s cutting-edge globally. If we succeed on this one, we’ll take on more projects.”

This is China’s new Silk Road in action. With the economy slowing back home, state construction companies are being put to work abroad, their projects backed by state loans. Although China says its plans are for the benefit of all, most jobs here will go to Chinese workers, and the loan that secured the contract – for nearly $2bn - was tied to a Chinese design.

Critics say China is exporting its problem of excess capacity at the expense of neighbouring countries, which will be left with white elephants and debt.

That’s not the builder’s concern, though. Xu Xiwen is focusing on delivering the contract on time.

Of all the challenges ahead, the one that worries him most is managing the workforce.

Not all of us have experience working overseas. We need to make sure negative emotions don’t accumulate and cause problems.”

China and Kazakhstan are neighbours but after two centuries of Russian domination, many Kazakhs are culturally closer to Russia. Russian is the chief language of business and culture. What’s more, two-thirds of the population are Muslim and there’s no pork in the local diet.

“We’re training our team about the local environment. We’ll respect each other’s habits and religions. Our canteens and dormitory areas will be separate so we don’t disturb each other.”

Xu Xiwen speaks neither Kazakh nor Russian and has no time to make local friends. He works seven days a week and misses his wife and son back in Beijing. But in his mind’s eye, he can already see himself - and them - travelling on the railway.

Artist's impression of the Astana railway

“I’ll bring my family here to see what I’ve built. And if all goes well, I’ll think about taking on bigger challenges.”

There will be plenty more, he says, on the new Silk Road.

“Every human being should strive for beauty. I like to dress as if I’m in Paris.”

Ardak Kubasheva has a queenly bearing and leaves home wearing a black velvet dress set off with silver jewellery and high stiletto shoes. All of which may be normal dress code in Paris but looks surreal amid the dust, potholes and derelict housing of Kenkiyak village in west Kazakhstan.

The decay of this village would be shocking anywhere but what makes it particularly so is that Kenkiyak sits on top of one of Kazakhstan’s vast oilfields.

The Chinese state oil company, CNPC, arrived 20 years ago and Ardak says things have gone downhill since then. She’s written countless letters complaining about polluted air and water and demanding work for the local community. But all to no avail, she says.

The Chinese have done nothing. There is such a huge oil industry here but still no jobs or facilities for young people. We want to live decently, so that we won’t be ashamed of our village.”

In her youth, Ardak dreamed of becoming an actress. But then she had three children and her husband abandoned her. “They were all girls,” she shrugs.

At 57, she is now a grandmother. But age has not mellowed her. She says there are growing numbers of disabled children in the village and suspects polluted water is responsible. She is outraged that a village kindergarten has become a hostel for Chinese workers. And she says locals can only get oil jobs by paying bribes.

Kazakhstan is an authoritarian country where critics of the government can go to jail - and the president welcomes investors on China's new Silk Road.

So no wonder few are as vocal as Ardak. In private, though, other Kenkiyak villagers admire her boldness and echo her complaints. One oil driller who paid a bribe for a job with a Chinese company says that he’s just quit after five years because he was treated like a slave - and that there is no point trying to get help from the courts because Chinese bosses have learned how to bribe them.

Even some Chinese admit to paying bribes. One engineer says his company pays backhanders, for a quiet life, when immigration officials come looking for illegal Chinese workers. “Everyone thinks the Chinese are rich,” he complains.

The capital, Astana, is dominated by futuristic skyscrapers - and soon it will have a futuristic Chinese railway to match. But the wealth that pays for it all comes from the oil fields hundreds of miles away across the steppe.

And there, in Kenkiyak, the air smells chemical and children climb on rubble for want of a playground. No wonder Ardak Kubasheva says the Chinese talk of win-win on the new Silk Road is empty for her.

“You see for yourself how our oil village looks. I feel sorry for my people. We see no help.”

Asked to comment, CNPC declined to respond.

“Chinese girls don’t have any idea about Stalowa Wola.

Sometimes when I go on a date and tell them I work in Poland, they even ask ‘where is Poland?’”

Hou Yubo is rueful about his failure to find a wife. Colleagues joke that this is his “key performance indicator” for 2017, but as a 36-year-old Chinese manager in a Polish steel town, it’s a hard one to meet. Especially as he’s surrounded by men.

“It’s like army life here.”

Hou Yubo is chopping vegetables in the kitchen he shares with other Chinese staff - 10 managers running a Polish factory and living the bachelor life. They work together, eat together, play football together. In fact, football is the accident that led Yubo to Poland in the first place. At 18, he was destined for languages at university and had set his heart on Italian or Arabic.

“On the day that mattered I was playing football and lost track of the time, so I missed the key meeting when courses were handed out. That’s how I came to study Polish.”

And that’s how Yubo came to Stalowa Wola and an empty love life. Set among the forests of south-east Poland, the town doesn’t even have a Chinese restaurant. Yubo and his colleagues have to drive the 150 miles to Warsaw to stock up on rice. There are no single Chinese women here. Even colleagues who are married have not brought their wives.

There’s really nothing for them to do, not even shopping. This is a town where the only stores sell alcohol… or medicine.”

Stalowa Wola means “steel will”.

It was founded on the eve of World War Two to make military equipment. When Poland’s wars were over, some assembly lines turned from building army tanks to bulldozers. But then came the collapse of the Soviet bloc and Poland turned west. The European Union was not short of companies making construction equipment and many of them were in trouble. The Stalowa Wola factory would have collapsed if Chinese giant Liugong had not bought it in 2011, as a bridgehead to world markets.

But survival is still a challenge.

Yubo says that back in China half the companies making bulldozers and excavators have gone bust in five years. Internationally the bloodletting is even worse. So finding a wife is not Yubo’s only key performance indicator. He needs the massive building work on China’s new Silk Road to save the factory.

He reasons that if the funding is to come from China, then his excavators and bulldozers should be the natural choice - Chinese equipment made by European workers.

We need political support. We’re providing the jobs and we pay tax here, so our machines should be used for these projects.”We are starving. So far it’s a lot of nice talk but it hasn’t yet translated into orders. ”

The factory in Stalowa Wola is China’s biggest investment in Poland to date. The company responsible is state-owned and the funds were provided by a state bank.

China’s state sector is notorious for misallocated resources and debt, and some critics fear the new Silk Road will be a virus through which it infects the rest of the world with its home-grown problems.

But in Stalowa Wola the 1,200 Polish workers who now rely on this Chinese state company are just grateful to have jobs.

Yubo chafes that the Polish assembly line is less efficient than the one in China - it's bigger but less productive, he says. But for a Chinese company in Europe, laying off workers is politically sensitive and will become even more so now that China has declared the new Silk Road will be a win-win for all.

As the manager who pays the wage bill, Yubo is impatient for real wins beyond the rhetoric.

The future is bright, but we really need the last kick to get that goal.”

As for the other goal, the wife hunt, Yubo is resigned to playing the long game. His parents have tried matchmaking and set him up with a string of dates but his trips home are too short for these efforts to succeed.

“I don’t have time to see films, get dinner, get coffee. For a good girl you have to invest – not only money but time. Time is the most valuable thing.”

Marrying a Polish wife would be as unthinkable as eating the wrong kind of rice. After serving up what his colleagues pronounce to be “the best Chinese meal in Poland but the worst in China”, he shrugs off their teasing about internet dating.

“Life is open still. You don’t know what the next chocolate in the box will taste like.”

Rafa has been helping his parents with the cows since before he can remember. He has the slow, gentle movements of a man whose life has been spent among animals. But the quiet exterior masks a sharp ambition. China may have plans for Poland but this 23-year-old dairy farmer has plans for China too. Pulling on his rubber milking gloves and boots, he grins.

China is a big market with people who need to eat. Our milk is GM-free, and it meets the highest health standards in the EU. We can offer China quality food.”

It’s a simple sales pitch but a strong one. Much of China’s soil and water is polluted, and regulators struggle to keep ahead of the tricksters. Its middle classes often mistrust the food that comes from their own farms and increasingly have the money to buy from abroad.

Dairy was at the heart of China's worst consumer confidence crisis in recent memory when infant formula laced with industrial chemicals poisoned hundreds of thousands of children. Rafa may spend several hours a day in a milking parlour, but he is well aware that China is haunted by fear of toxic milk.

Rafa’s dairy is a world away from a Chinese factory farm. It sits amid forests and lakes, close to the village of Piatnica, in a part of north-east Poland known as the country’s “green lungs”.

Tradition has kept holdings small and farming practices honest. On this farm there are 99 milking cows and 40 calves. But to apply strength through numbers in the marketplace, Rafa and his parents have joined a dairy co-operative. And as the European milk market shrinks, they’ve encouraged the co-operative to explore China.

The milk truck arrives while we are talking. Rafa says it has to come twice a day now because the technology he’s introduced is helping raise milk yields and the existing tank on the farm is no longer big enough.

On his smartphone Rafa shows me the bio-data readings from each cow’s collar and explains how the grain dispenser then measures out the correct feed quantity for each animal. A robot cleaner moves among the herd. And even when he’s inside the house, Rafa can check all is well via CCTV cameras.

He hopes to expand.

Just across the border in Belarus and Ukraine, Chinese companies are investing in huge tracts of farmland and dairy herds tens of thousands strong. But here in Poland buyers must be locally registered companies, and Rafa wouldn’t dream of parting with his farm.

This is my father’s land and my grandfather’s before him. Now I intend to put my mark on it. I don’t want to sell up and have only money to show for it.”

But he does hope to take advantage of Chinese ambitions to advance his own. Poland is an important country on China's new Silk Road, a transit point on its land route to European markets. With regular rail freight services heading west but little to fill those trains on the return journey, with a Chinese commitment to provide chances for partners along the route and at the other end a market thirsty for healthy milk… that surely adds up to an opportunity.

In the milking parlour, one cow sways out, and an automatic gate opens to let the next amble in. Rafa gives it a pat on the rump and wipes its udder, every move measured and patient. China’s strategic jigsaw may be falling into place, but his is taking shape too. This is not a dairyman to be daunted by warnings that the distance is immense, the Chinese bureaucracy notorious or the market complex.

We want to try. We’re learning from experience to dare to think bigger.”

“There is no right answer. Cream or jam is fine.”

So says 34-year-old Tingting He, in answer to the question of which to spread on the scone first in a British cream tea.

It’s a relief to learn that I haven’t been doing the wrong thing all my life.

We’re in the Essex tea room of an upmarket British jam maker and on the table before us is a plate of fluffy scones, a bowl of clotted cream and miniature jars of strawberry jam.

Tingting may be Shanghainese but she’s giving me a lesson in the British tradition of afternoon tea. As brand ambassador for Tiptree Farm she delivers the same lecture in China’s top hotels. Her home country may claim to be a communist state, but it has a healthy appetite for the branding and rituals of the British ruling class. Tingting brings Chinese buyers for a tour of the Tiptree fruit farm.

Tingting He and Carrie Gracie

“It’s refreshing for them. They’re paying for the countryside with the birds singing. There are lots of rumours about Chinese food sources, so the quality gives them peace of mind. And also they know the Royal Family has issued us with a royal warrant. That gives them another level of security.”

It’s easy to see why Chinese visitors might enjoy the tour. Tiptree exported its first jar of jam in the late 19th Century and still has some of the rambling walled gardens and ancient orchards of that era. Inside the jam factory, the scent of simmering strawberries gives way to a hot wave of orange marmalade. And then the heady spices of the Christmas pudding room. Tingting says she loves the tradition of setting light to the brandy. She thinks she can sell Christmas puddings in China.

People like something festive, a good gift over Christmas or Chinese Spring Festival. It’s special, unique. They’re very curious and open-minded.”

British food is not fabled in China. But on a state visit to the UK in 2015 the Chinese president was filmed eating fish and chips. And walking between pallets piled high with jams and chutneys, Tingting is excited about China’s new breed of gastronomic adventurers.

“The more they read and travel and encompass different food cultures, the more they try new things. Blueberry jam is something they are willing to try. Cheese and redcurrant jelly. At the start they found it strange but now they think it’s good. They are inventing their own way of getting Western food into their culture, which is very exciting for us. ”

When Tingting says “us” she means Tiptree. After many years studying in the UK, and with a British fiance, the Essex farm is as big a part of who she is as Shanghai.

But the hard fact for exporters is that China is a long way away. Sea freight can take two months. Tingting hopes the rail freight service on the new Silk Road will shrink the time to market. When the train gets refrigerated containers next year, it should become possible to deliver British scones and Devon clotted cream. She dismisses my suggestion to bake the scones in China.

“You can’t do that because British water and flour make for the special taste.”

Once a symbol of British empire and engineering, now it’s China’s great age of the railways. The overland freight service from the UK began this year, carrying British hopes for post-Brexit markets from one end of the new Silk Road to the other. Tingting is impatient for faster progress.

“It will make a big difference when it’s developed. The train network gets us everywhere, so for products with a short shelf life like cakes and fruit it’s a good option.”

Thinking about rail freight gives Tingting another idea – perhaps Tiptree could use the Chinese train to deliver chutneys to Europe?

For her the new Silk Road is one long opportunity stretching all the way back to China. None of it is easy but to those who shun China as a difficult market, she counsels strategy, patience and courage.

“You really need to find a good long-term partner. It might take more than a year or two to make anything happen. But if you don’t knock you won’t know.”

I hoped that after travelling the new Silk Road I could tell you I’ve got the measure of it. But after weeks in a suitcase through China, Central Asia and Europe, I find it hard to judge.

China’s “project of the century” is just so vast and so vague, it may take a century to grasp its significance.

I only travelled one section of it – the overland route to Europe. There is a lot more. The project’s official title is the Belt and Road Initiative – the first half of which refers to overland routes fanning out to the north, west and south, and the other half to shipping routes crossing the Western Pacific and the Indian Ocean.

New Silk Road promotional map

There will be success stories because Chinese-built infrastructure can be a good thing. But some projects will fall victim to corruption or political instability. Others will simply be the wrong project to begin with.

I fear I saw that at first hand in Kazakhstan.

Xu Xiwen may deliver a magnificent light rail system for Astana.

But I’d just been sitting in traffic jams in Almaty, the country’s busiest city, and bumped for hours along the potholed roads of west Kazakhstan. A driverless commuter railway for the under-populated capital wouldn’t have been top of my priority list for nearly $2bn of public cash.

For China, building things is easy. It’s building the right things and then making them commercially viable that is harder.

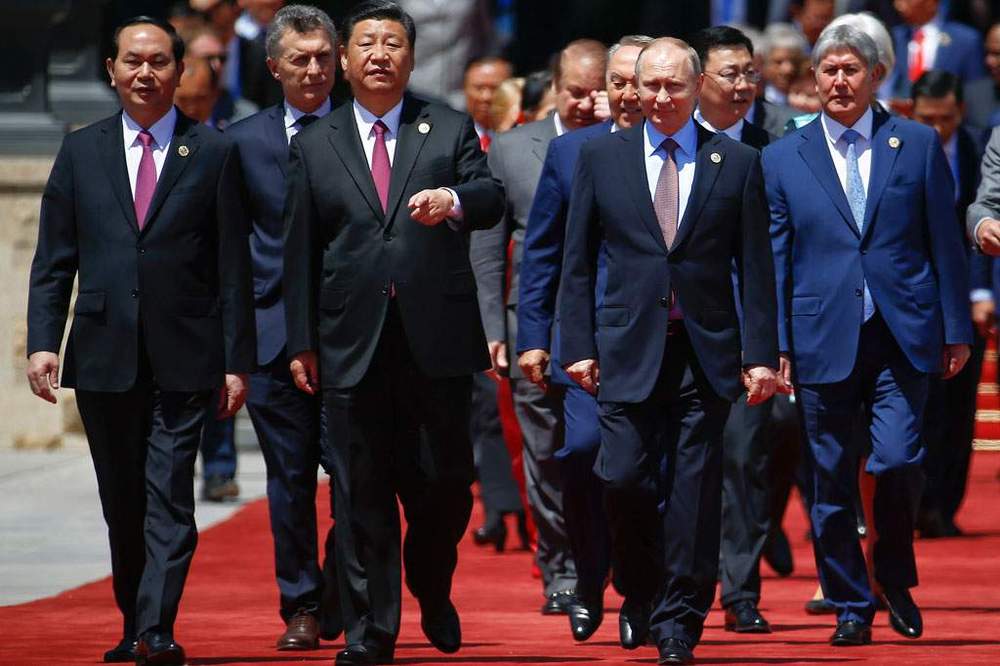

Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin at the Belt and Road Forum, 2017

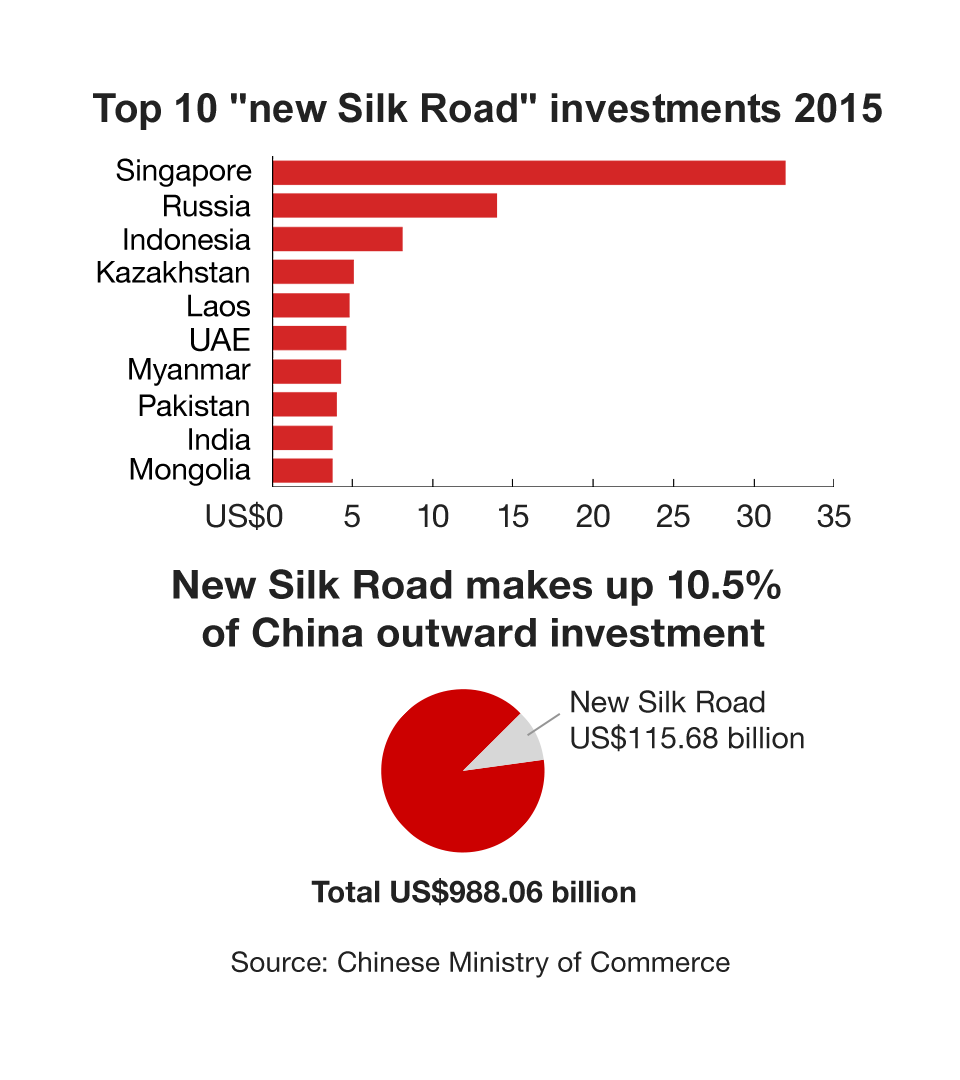

President Xi Jinping’s new Silk Road is a political vision driven by state construction companies and state funds. On all my travels, I saw little sign of China’s private sector. The year 2016 was the biggest in history for Chinese outbound investment but most private money was going to the developed world. And among countries on the new Silk Road, the top destination was Singapore… which is hardly in urgent need of infrastructure.

Xi likes to say he’s rebuilding the old Silk Road, but that grew organically, not as the product of a political diktat. China’s 21st Century merchants will follow the camel trains of the past only if they can believe in a return on investment, and preferably transparency and good regulation too.

As for the free trade part of Xi’s message, there’s no sign of fortress walls tumbling yet. China is certainly hungry for healthy food and novelty, which may bode well for Polish milk or British cream teas. But the president will have to do more than munch apples in Warsaw and deliver warm words at Davos if his win-win rhetoric is to bring more than a trickle of containers on the eastbound train.

The biggest problem with the new Silk Road is the lack of debate. Most problems are correctable if they are at least acknowledged. But Xi’s insistence on “positive energy” puts all talk of pitfalls off limits, and such censorship can be costly, perpetuating mistakes. At home China has learned this lesson many times. But now it is embarking on a huge experiment in the world.

My tale is over. Let others take up the story.