Warning: Graphic content

On 23 June 2018, a series of horrifying images began to circulate on Facebook.

One showed a baby with open machete wounds across his head and jaw. Another – viewed more than 11,000 times – showed a man’s skull hacked open. There were pictures of homes burnt to the ground, bloodied corpses dumped in mass graves, and children murdered in their beds.

The Facebook users who posted the images claimed they showed a massacre underway in the Gashish district of Plateau State, Nigeria. Fulani Muslims, they said, were killing Christians from the region’s Berom ethnic minority.

A massacre did happen in Gashish that weekend. Somewhere between 86 and 238 Berom people were killed between 22 and 24 June, according to estimates made by the police and by local community leaders.

But some of the most incendiary images circulating at the time had nothing to do with the violence in Gashish. The image of the baby, which was shared with a call for God to “wipe out the entire generation of the killers of this innocent child”, had first appeared on Facebook months earlier. The video in which the man’s head was cut open did not even come from Nigeria, it was recorded in Congo-Brazzaville nearly a thousand miles away, in 2012.

But the truth didn’t matter. The images landed in the Facebook feeds of young Berom men in the city of Jos, hours to the north of the rural district where the massacre was happening. Some of the Facebook posts suggested that the killings were happening right there in Jos, or that the inhabitants of the city were about to be attacked. Few stopped to question the claims, or to check the origin of the graphic pictures that were spreading from phone to phone.

“As soon as we saw those images, we wanted to just strangle any Fulani man standing next to us,” one Berom youth leader told the BBC. “Who would not, if they saw their brother being killed?”

The images helped to ignite a blaze of fear, anger, and calls for retribution against the Fulani – a blaze that was about to engulf a husband and father called Ali Alhaji Muhammed.

Photo of Ali Alhaji Muhammed

Ali was a potato seller from Jos, a city of around a million people.

On 24 June he went to a town called Mangu to meet some customers. It was a journey he’d made hundreds of times. He left shortly after morning prayers and expected to be back in time for dinner with his wives Umma and Amina and his 15 children.

On his way home in a shared taxi, Ali found the road blocked by a wall of burning tyres. A mob of Berom men armed with knives and machetes were interrogating drivers, looking for Fulani Muslims.

Ali was dragged from his car along with another male passenger. His charred remains were found three days later near the edge of the Jos-Abuja highway. His body was so badly mutilated his wives refused to see it.

Ali was one of 11 men who were pulled out of their cars and killed on 24 June.

Some were set alight. Others were hacked to death with machetes. Days later, their bodies were still being discovered across the city, dumped in ditches, behind houses and along the roadsides. Many were burnt beyond recognition.

One of the vehicles destroyed on 24 June 2018 in Jos

Hostility between the Fulani and the Berom predates the rise of Facebook. But the police and the army in Plateau State are convinced that the graphic imagery and misinformation circulating on the platform on 23 June and 24 June contributed to the reprisals.

“It was the pictures, the supposed pictures that emanated from the attack [in Gashish],” said Tyopev Terna Matthias, public relations officer for the Plateau State police. “Jos South was not under attack. But because of those images they saw, the next day, roads were blocked. People died. Vehicles were burned. So many people died.”

It was not the first time Matthias had seen incendiary posts on social media followed by violence in the towns and villages of Plateau State. “Fake news on Facebook is killing people,” he said.

Because of those images roads were blocked. People died. Fake news on Facebook is killing people

In the US, Asia, and Europe, Facebook has come under intense scrutiny for its role in the circulation of “fake news”. But what happens when viral misinformation is allowed to spread through areas of Africa that are already in the midst of ethnic violence? And what is Facebook doing to ensure its platform is not being used to disseminate lies, spread fear, and foment hatred in Nigeria’s troubled heartland?

“Next stop: Lagos!” Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg posted to his account in August 2016.

It was his first trip to sub-Saharan Africa and he was excited, he said.

Who wouldn't be? Some 53 million mobile internet users are forecast to come online in Nigeria over the next seven years: a lot for a company that partly measures its success on user growth.

When Zuckerberg touched down in Lagos, there were 16 million monthly Facebook users in Nigeria. Today, just two years later, there are 24 million.

But more users means more content, and a lot of that content, according to the police in Plateau State, is false, misleading, and dangerous.

Facebook is aware of the problem, and claims to be addressing it. “Nigeria is important to us,” said Akua Gyekye, the company’s public policy manager for Anglophone West Africa, in a recent statement. “We are committed to taking our responsibility seriously in tackling the spread of false news.”

Facebook told the BBC that it is pursuing a “multi-pronged approach” to combating the spread of misinformation in Nigeria. “As well as reports from our community, we’re using machine learning tools to help find and remove inappropriate content, are investing in local partnerships, and continue to engage with Nigerian civil society, NGOs, academics and policy makers.”

At the centre of Facebook’s efforts is a scheme that it calls the “third-party fact-checking programme”. The programme is part of a worldwide approach that Facebook has already rolled out in 17 other countries.

In Nigeria, the programme launched in October and the third parties are the French news agency AFP and the non-profit organisation Africa Check. Their fact checkers will review stories that have been picked up by Facebook’s automated system for detecting false information. The system includes posts that have been flagged as false or misleading by other Facebook users.

“We know there is no silver bullet,” said the Facebook spokesperson, Akua Gyekye, “but once a fact checker rates a piece of content as false, we are able to reduce its future views by an average of 80%”

The statistic sounds impressive. But BBC Africa Eye dug deeper into Facebook’s fact-checking initiative in Nigeria, talking to insiders and experts in the field. And when we got into the detail the picture looked rather different.

So far, Facebook’s third-party fact-checking partners, AFP and Africa Check, have committed just four people full-time in Nigeria to analysing and debunking false news, on a platform that is used by 24 million Nigerians every month.

Alexios Mantzarlis, director at the International Fact-Checking Network – the body that accredits fact-checking agencies – told us that an individual fact checker might be able to complete “between 20 and 100 individual fact checks” per month. But in Nigeria, where reliable public data is hard to find, the process is often slower. Another source working for one of Facebook’s fact-checking partners, who asked not to be named, said that fact checkers sometimes debunk just five stories in a week.

“They are just dipping their toes in the water,” said Gbenga Sesan, a Nigerian digital rights activist who has met Facebook representatives to discuss the company's expansion in Nigeria. “At the end of the day, these are business people and they want to make more money,” he said.

Julie Owono, the Cameroonian director of Internet Without Borders, a digital activist group, believes that Facebook’s plans are not commensurate with the scale of the problem. “There’s a dis-proportionality between the threat and the effort put in place,” she said. “Four fact checkers?... It’s scary.”

More worrying still is that none of the four fact-checkers deployed full-time by Facebook’s partners in Nigeria speaks Hausa, a language spoken by millions in the country.

Facebook told the BBC that their Nigerian fact checking partners “support Hausa.” The company later clarified this means the fact-checking teams can receive support from Hausa speakers in their network when required.

The BBC analysed more than 50 recent posts written in Hausa that contain hate speech or false information – and some of them are horrifying.

One post, for example, contains a photo of a person slumped on the ground, their skin burnt and peeling. The Hausa text reads: “This is John Okafor [an Igbo name] who tried to smoke weed using pages from the Qur’an and got burnt, instantly.”

In fact, the photograph was taken after a horrific assault on a woman accused of witchcraft in Lagos in 2014. She was reportedly burned alive and later died of her wounds.

But the facts didn’t matter to the person who created this post, and didn’t register with the people who liked it. What they saw was a story about a Christian – an ethnically Igbo Christian – displaying contempt for Islam, the predominant faith of Hausa-speaking Nigerians. It is the kind of story that, in a region already torn by ethnic and religious violence, can have dangerous consequences.

A Nigerian Facebook user browsing

“Anything you do in the world is better when you’re with your friends,” Mark Zuckerberg said in a 2011 interview with the BBC, back in the early days of Facebook’s global expansion. “Bringing those kind of experiences to people in all these different places is really cool.”

Seven years on, Facebook’s optimism has been tempered by criticism of its role in electoral controversies in the US and the UK, and by allegations that the platform is being used to spread divisive rhetoric and false information from Cameroon to Myanmar. “Fake news is not our friend,” said an advert promoted by the company earlier this year.

In a statement to the BBC, Facebook said any suggestion that they “are not fighting abuse on Facebook in Nigeria is misleading”.

“We know we have a responsibility to keep people safe and prevent the spread of misinformation and continue to work hard to fight any abuse,” the company said.

But misinformation and graphic imagery continue to circulate on the platform.

We sent Facebook the video of the man’s head split open – the clip that was filmed years ago in Congo-Brazzaville, but which spread across Plateau State in the hours of the reprisal attacks in June this year. Facebook immediately removed the post, saying that it violated its policy on violence and graphic content.

But a quick search of Facebook the following day revealed the same distressing film in other posts, still circulating and still accompanied by the false claim that it showed a massacre in Nigeria. Since it was first uploaded to Facebook in 2012, the video has been used to whip up fear all over the continent. One user claimed it showed an attack in Kinshasa, capital of Democratic Republic of Congo. Another said it showed a Boko Haram atrocity in northern Cameroon.

Where will this video appear next? And to what ends will it be deployed?

Few organisations have a better understanding of the impact of “fake news” in Nigeria than the police in Plateau State. They told the BBC they were constantly monitoring Facebook for “fake information and fictitious pictures”.

Plateau is where the Gashish massacres happened back in June, and where Ali lost his life in the reprisal attacks that followed.

“We surf Facebook as much as possible,” said spokesman Tyopev Terna Matthias, sitting at his desk in the crumbling police headquarters, which is surrounded by bomb-proof concrete bollards. Matthias has a team of 10 officers monitoring the platform for false information, he said, split between his personal office and a separate communications department.

And for these men, the burden does not end with monitoring.

Matthias recalled a recent incident in which someone called the police, alarmed by a Facebook post saying that men were on their way to attack his village. Vehicles loaded with officers were deployed to the village, where they waited for two days before concluding that the post was false.

That had happened many times, Matthias said, but the police could not risk ignoring the threats that circulated on Facebook: “Villages in Plateau are under constant attack,” he said. “So when we get this information, we take it seriously. Then we discover it's fake. It wears us down.”

Villages in Plateau are under constant attack. So when we get this information, we take it seriously. Then we discover it's fake

In order to prevent panics like this, which drain the resources of a police force that is already over-stretched, Matthias’s men use Facebook to debunk false information whenever they find it on the platform. At times of crisis they even use their personal accounts to quash the rumours, and they call on community leaders to do the same. But the sheer volume of misinformation circulating in Plateau State is overwhelming their efforts to counteract it.

In addition to the roadblock attacks that cost Ali his life, Matthias can cite more than a dozen incidents when he believes false information on Facebook played a role in inciting murder, assault or civil unrest: a riot which damaged government property in late June 2018; a stampede in the streets of Jos following false claims of an attack; the killing of two Igbo men by a mob in September 2017.

“It causes panic,” he said. “Fake news is doing a lot of damage to our society. We pray Facebook shall listen to us and do something fast.”

Policeman guarding the police headquarters in Jos

The Nigerian army in Plateau State shared Matthias’s view.

Between September and October, they debunked seven false stories on Facebook. In addition to monitoring the platform, they hold regular meetings with local imams, pastors and politicians to raise awareness of the threat.

“It’s a new realm of warfare,” said Major-General Augustine Agundu, the commander of a large peacekeeping operation in the state. “[Fake news] spirals before you know what’s happening. You have to spend a lot of effort to let people know that it is false.”

Major Adam Umar, a senior information officer in the Nigerian army, said his team has set up a helpline for local people to report “fake news” and that the army is now using radio broadcasts to debunk false stories.

“It’s turning one tribe against another, turning one religion against another,” he said, days after returning from a peacekeeping mission. “It has set a lot of communities backward.”

It’s turning one tribe against another, turning one religion against another. It has set a lot of communities backward

Umar witnessed the aftermath of the massacre in Gashish in June. He, too, believes that “fake photographs” on Facebook played a role in igniting the reprisal attacks in Jos. He also recalled a similar incident that occurred last year, when Igbo and Hausa men clashed following the spread of images purporting to show an attack in the east of the country.

The country's fight against “fake news” on social media is not confined to individual police forces in Plateau State. In 2018, the Nigerian government announced a nationwide campaign to raise awareness about the problem.

Lai Mohammed, Nigeria’s minister of communications, spoke at the launch of the initiative in June. “In a multi-ethnic and multi-religious country like ours,” he said, “fake news is a time bomb.”

According to the Nigerian Communications Commission, more than 100 million people now use the internet in the country – triple the number of users in 2012. Millions more are expected to go online over the next few years, and Facebook is doing its part to help Nigerians connect.

During Mark Zuckerberg's 2016 trip to Nigeria, Facebook rolled out its Free Basics service in partnership with Airtel Africa, a mobile phone network. The service gave users access to 80 pre-selected websites without having to pay for data. Among those sites was Facebook.

For millions of young people in Nigeria, the platform has become an integral part of everyday life. “It makes the world close,” said 18-year-old Denis Davou, who joined Facebook in 2015 and has 2,000 friends on the platform. “We tend to have friends around the world and we chat. We tend to know things about other countries, and they should also know about our country,” he said.

“I log in every day and I have like 3,000 friends,” said 17-year-old Pam Finna, who lives in a suburb of Jos.

Denis and Pam are sincere in their appreciation of Facebook, and their comments are in line with Zuckerberg’s stated aim of “connecting the world”.

But Denis and Pam, like many Facebook users we spoke to, admitted that they had no idea how to report the upsetting or frightening images that appeared on their phones. They belong to the Berom ethnic minority group and often see posts that vilify their people.

Jos residents Pam and Dennis with their friends

They are not alone in this, many young Nigerians remain unsure how to identify “fake news” or report it.

“Most people who post have no idea what they’re posting or reposting because they themselves are not media literate,” said Muhammad Bala, a professor of mass communications at Bayero University. “They don’t understand motives, they don’t understand intent, they don’t understand underflowing currents of other things.”

This lack of basic media literacy leaves them vulnerable to the kind of dangerous misinformation that is seen by thousands on Facebook in this region.

Facebook told the BBC it was addressing the issue of media literacy. The company said that, in addition to their fact-checking initiative and machine learning tools, it has recently launched an “online safety and digital literacy youth programme” with 140 Nigerian secondary schools.

But again, there is a problem of scale. Nigeria has more than 54,000 secondary schools – to say nothing of the millions of Nigerian children who are not in school at all.

“The owners of Facebook should be doing much more,” said Dr Sam Godongs, professor of political science at Jos University. “Social corporate responsibility is part of the ethics of doing business… If you allow fake news to keep generating and brewing hate, then you are invariably killing people.”

In Nigeria, the lines between misinformation and hate speech are often blurred.

What is clear is that, despite Facebook’s attempts to root out hate speech, and the efforts they are making to detect and remove false information, hundreds of inflammatory posts are slipping through the net.

Some of these posts report real atrocities, but are couched in language designed to incite ethnic hatred. Others spread false reports of killings. Many contain half-truths –rumours and insinuations that spread from phone to phone in the villages of Nigeria’s Middle Belt, unnerving communities who are already frightened by the violence of recent years.

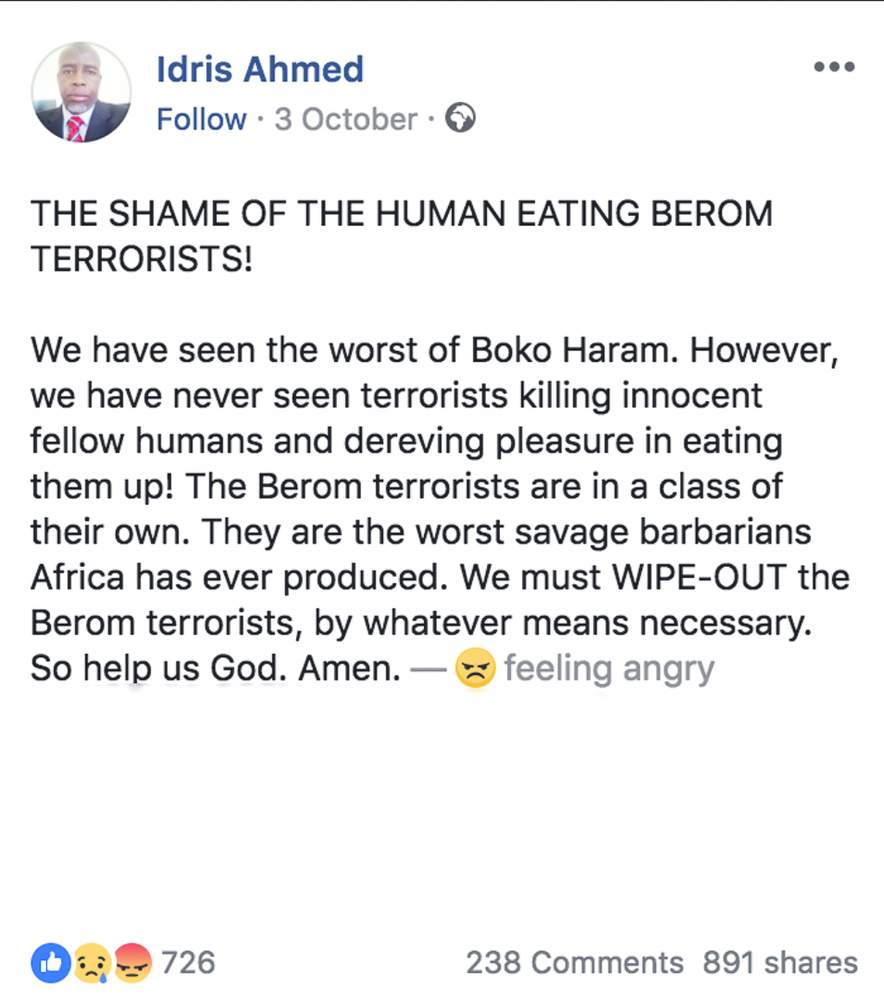

One divisive figure operating in this murky terrain is Dr Idris Ahmed, who has been singled out by the Nigerian army as an online troublemaker.

Photo of Idris Ahmed from one of his Facebook profiles

Ahmed is a living example of the complexity of the problem facing Facebook. He is based in the UK and runs an organisation called Citizens United for Peace and Stability. He says he was born in Nigeria, has British nationality, and identifies as Fulani. But from the safety of a suburban house in Coventry, Ahmed is sowing fear in Plateau State.

“We have seen the worst of Boko Haram,” he wrote on 3 October 2018, in a post shared more than 890 times. “However, we have never seen terrorists killing innocent fellow humans and deriving pleasure in eating them up! The Berom terrorists are in a class of their own. They are the worst savage barbarians Africa has ever produced. We must WIPE-OUT the Berom terrorists, by whatever means necessary.”

The words “savage” and “barbarians” are shocking, but “terrorists” is the key term here. Ahmed has used it repeatedly when referring to the Berom, coupled with calls for them to be “wiped out”. By doing so, he couches his calls for annihilation in terms that suggest he is referring to violent political criminals and not to an entire ethnic group. He has called Berom people “terrorists” in at least nine Facebook posts this year.

There is no nationally or internationally recognised Berom terror group. And while Berom people have committed killings during Plateau State’s crisis, the Berom people as a whole are not engaged in violence.

Screenshot of Facebook post by Idris Ahmed on 3 October 2018

Some of Ahmed’s followers, however, echo the dehumanising language he uses to describe Berom people. A comment below one of his posts calls for the Berom to be “wiped out” and labels them “savage and barbarian”. Another reads: “Kudos for exposing these silent killers, hope the military would respond with fire and fury and reduced them to greasy spots!”

Ahmed is not the only Facebook user to deploy divisive and violent language against Berom people. In the Hausa language, Facebook posts calling for the Berom to be “wiped out” are even more explicit. “Security forces must ignore Amnesty International and wipe out Biroms totally,” posted one Hausa user to his roughly 5,000 followers on 25 June. “They should go there with sophisticated weapons and kill all the humans, animals and even birds.”

In September this year, Ahmed used Facebook to make an unsubstantiated claim about the death of a retired general. His post insinuated the army was involved in the killing, exacerbating an already tense situation. The Nigerian army was incensed.

“We dare Dr Idris Ahmed to provide evidence to support his infantile claims,” wrote Texas Chukwu, the Nigerian army’s public relations director, in response to Ahmed’s post. He called Ahmed’s claims about the disappearance of the general “imbecilic” and “completely out of sync with reality”.

Members of the Berom ethnic group in Jos have also expressed serious concerns about the impact of Ahmed's Facebook activity.

“Idris is an element of destruction,” said Joshua Pwajok, a Berom youth leader who lives in Jos. “He has succeeded in building an army of hatred, an army among his people.”

Sam Godongs, professor of political science at Jos University, reflecting on the overall issue of hate speech and “fake news”, fears that Facebook does not understand the seriousness of the situation. “Cumulatively this is responsible for genocide,” he said. “How I wish [Facebook] were aware of the gravity of what we are facing. And if they are aware, I am wondering why they are so inactive or insensitive. We are talking of human lives.”

Facebook told the BBC it has teams which are “dedicated to preventing false news and polarisation from contributing to real world harm”, especially in countries where “it has life and death consequences”. The company said it is hiring new dedicated staff to address such issues around the world, but did not disclose any specific details regarding Nigeria.

Facebook cannot claim to be unaware of Idris Ahmed.

His account has been suspended twice, once in 2016 and again in 2017, only to be reinstated a few days later. BBC Africa Eye reported one of his posts about “wiping out” Berom “terrorists” to Facebook on 8 November. The company removed the post the following day and disabled Ahmed’s account for a third time. His second Facebook account however – which has more than 30,000 followers and on which he has also referred to “Berom terrorists” – remains active.

Ahmed did not respond to the BBC's request for a formal comment in time for publication. In a phone conversation, he described the BBC's description of his Facebook account as “grotesque” and said it did not fairly reflect his character.

“I will try to recover the [disabled] account, by making the Facebook administrators see sense,” he told his followers on 10 November. “Pray for our success,” he said.

In October, the BBC visited the home of Umma and Amina, the widows of Ali, the potato seller who was killed at the roadblock in June.

On the road into the village, at the place where Ali was dragged from his car, the tarmac was still blackened from the tyres that burned at the roadblock. There were several more spots like this, dotted around Jos South – fading reminders of the 11 men who were killed, and of that fact that, in central Nigeria, “fake news” can ignite real violence.

At first glance, Ali’s home was a picture of domestic peace. A little girl was reading through a school textbook while her brother and sister chatted among themselves. Two younger children dashed inside to fetch something. Amina sat on a makeshift stool washing clothes in a large bowl, a baby strapped to her back. Umma, Ali’s first wife, crouched in the corner washing kitchen utensils.

But the silence in the room made it clear that something was amiss. And when Umma started to talk about her husband of 20 years, she could not keep from crying.

Ali's youngest wife Amina

Wiping away tears with a pink head scarf, she recalled a kind, funny, and generous man. He loved children, she said, and in addition to his own he adopted two of his nephews after his brother died. When Ali went away on business, he always came home with biscuits for the kids.

“He used to play with them so much,” Umma said, looking at the small faces huddled behind her. “If he was here, you won’t see these children around.”

Umma and Amina were getting by with help from the local community, who were horrified by Ali’s death. They were slowly trying to piece their lives back together, in the hope of peace for their region.

“You see that our child, that small one,” said Umma, glancing towards one of the young boys in the courtyard.

“Every day he talks about it, saying ‘Mummy, I am going to buy a gun and shoot those who killed my father.”