It’s clear which one Patricia O’Brien thinks he was as she rifles through a thick bundle of pages, each with an official looking logo in the top right-hand corner.

She’s been a one-woman detective agency for four years.

She believes Omagh bricklayer Noel Knox killed her younger sister, Mairéad McCallion in 2014.

And she holds him responsible for the deaths of at least two other women: Diane Conway in 2002 and Katrina Fulton in 2003.

All three were alcoholics who drank with Knox.

People in the County Tyrone town believe he was also linked to the death of a fourth woman.

“It was just through talking to other people in Omagh that we suddenly became aware that Mairéad was his fourth partner to die in very tragic circumstances,” says Patricia.

“I have autopsy reports, forensic reports, I have information from the coroner’s service.”

Each report details the bruises, violent injuries and the ravaging effects alcohol had on her sister’s body.

But Patricia holds Noel Knox responsible.

He died almost a year ago to the day - after suffering a blood clot at the age of 53.

There’s a story here. There’s a story that has to be told.

Omagh is a town that knows tragedy: most people you speak to have a link to the devastating Real IRA bomb in 1998.

Twenty-nine people, including a woman pregnant with twins, were killed that day - among them was Mairéad McCallion’s best friend.

Mairéad was 21 at the time.

“My mother in particular noticed Mairéad sinking into a depression as a result of the Omagh bomb,” says Patricia.

“And another serious incident happened around that time too.”

Patricia describes Mairéad as a timid girl who became the victim of a bully when she went to university in Dundee to study accountancy.

After she was beaten up on a night out, she dropped out.

Never to return.

Many people who knew Mairéad talk about how bright she was. How good her memory was.

She was the second youngest of eight and, according to Patricia, “probably the most intelligent in our family”.

After she returned to Northern Ireland, she began a traineeship with an accountancy firm, but alcohol took hold.

“She was set on a path of destruction,” says her sister.

“My mother would have said Mairéad is choosing alcohol to try and dull the pain of what she’s been through.”

After a while, Mairéad found comfort in the arms of a local man, Noel Knox.

Theirs was a violent relationship and on the morning of 23 February 2014, Knox called the police asking them to remove her from his property.

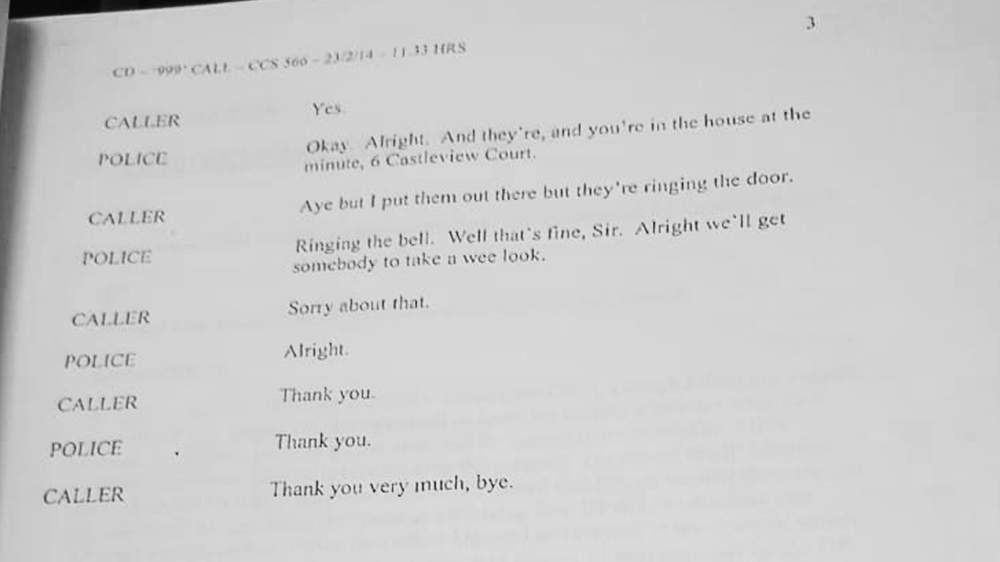

Transcript of 999 call

“There’s a disturbance at 6 Castleview Court in Omagh,” Knox said, according to the 999 call transcript.

He’d already thrown her out of the house into the cold Sunday morning. She wasn’t wearing shoes and was banging on the door and window, demanding her coat and handbag.

Knox had told Mairéad not to let anyone else in while he was out drinking at a nearby house.

But she’d let in a man known as “Clown” who asked her to phone Noel.

He came back in a rage, shouting at them both to get out.

When officers arrived, Mairéad showed them a fistful of her brown hair and told them: “He pulled my hair, banged my head and threw me into the garden.”

Mairéad died the next day. After spending hours at the police station, she began vomiting and passed out in the police car as she was brought to a friend’s house.

She was rushed to hospital but it was too late.

Patricia and the family were called to come and say their goodbyes.

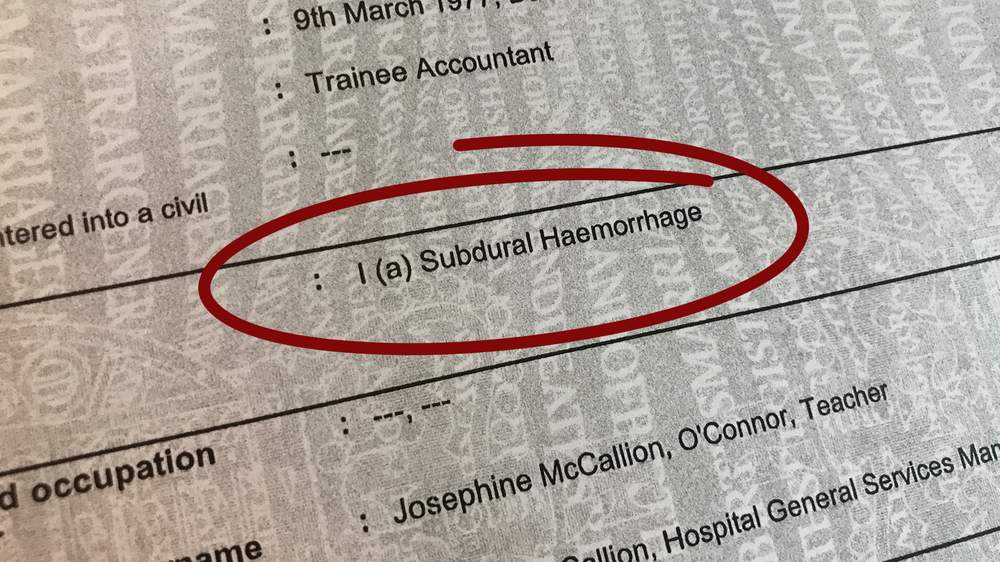

Mairéad McCallion's death certificate

Under “cause of death”, her death certificate reads: “Subdural haemorrhage” - a bleed in the brain.

It’s something that haunts Patricia O’Brien.

“There was only police involvement in Mairéad's death because Noel Knox phoned the police to remove her from his house,” she says.

“Had he not done that we’d have never known the truth on that day.”

We have always known that Noel Knox killed Mairéad, there was never any doubt in our minds.

Noel was arrested and charged with murder. It would be as close as he would ever come to sitting in a dock, as prosecutors withdrew the charge seven months after Mairéad's death.

The McCallion family were told the evening before he was due in court for a remand hearing.

The Public Prosecution Service (PPS) had been told a further medical report had cast doubt on the cause and timing of Mairéad’s death.

In 2017, an inquest was finally held. Last autumn, coroner Patrick McGurgan went as far as it was legally possible to go in blaming Knox for Mairéad’s death.

“I find that the trauma sustained was an impact to the deceased’s head and that it occurred on the morning of Sunday 23 February 2014 whilst the deceased was being removed from 6 Castleview Court by her then partner,” he said.

Coronial law restricts the naming of blamed individuals, but it’s clear who Mr McGurgan was referring to.

Violence had been a hallmark of Mairéad’s relationship with Noel Knox.

People remember her being frail and unsteady on her feet, aggravated by her alcoholism.

She had a propensity for falling and banging into things.

But she was also being hit, it seems regularly, by Knox.

Her autopsy recorded three pages outlining injuries to her body, including more than 50 bruises.

“The abuse was horrific,” recalls Patricia, who only discovered the extent of the violence when Mairéad first admitted it to the family two years before her death.

“It was at times of a sexual nature, it was very manipulative. It was very controlling.”

And, it seems, the violence was documented.

Police found photographs of Mairéad’s injuries on Knox’s phone.

There was one particular photograph… police told us she had two black eyes and a broken nose... he had it as his screensaver.

On occasions Mairéad had gone to police, but she had a tendency to backtrack.

A letter in her neat handwriting was discovered in a jotter after her death:

I made an accusation of assault. To me it was not an ‘accusation’ because the assault did happen.

“But my reasoning for withdrawing my statement is for personal reasons.

"However I do want to state the fact that I do not tell lies.

“To put it in a nutshell, I cannot go through this again. I apologise to the PSNI.

"Did he put me up to this?

"Well I think everybody knows the answer to that question.

“Again I want to state the fact that I want to withdraw my statement. No proceeding against Mr Knox.”

The jotter also contained poetry.

Mairéad would create black humour, punning Knox with knocks to describe how he would "knock her lamps out".

The famous Ulster colloquialism fused with his surname in a play on words - but there was nothing playful about it.

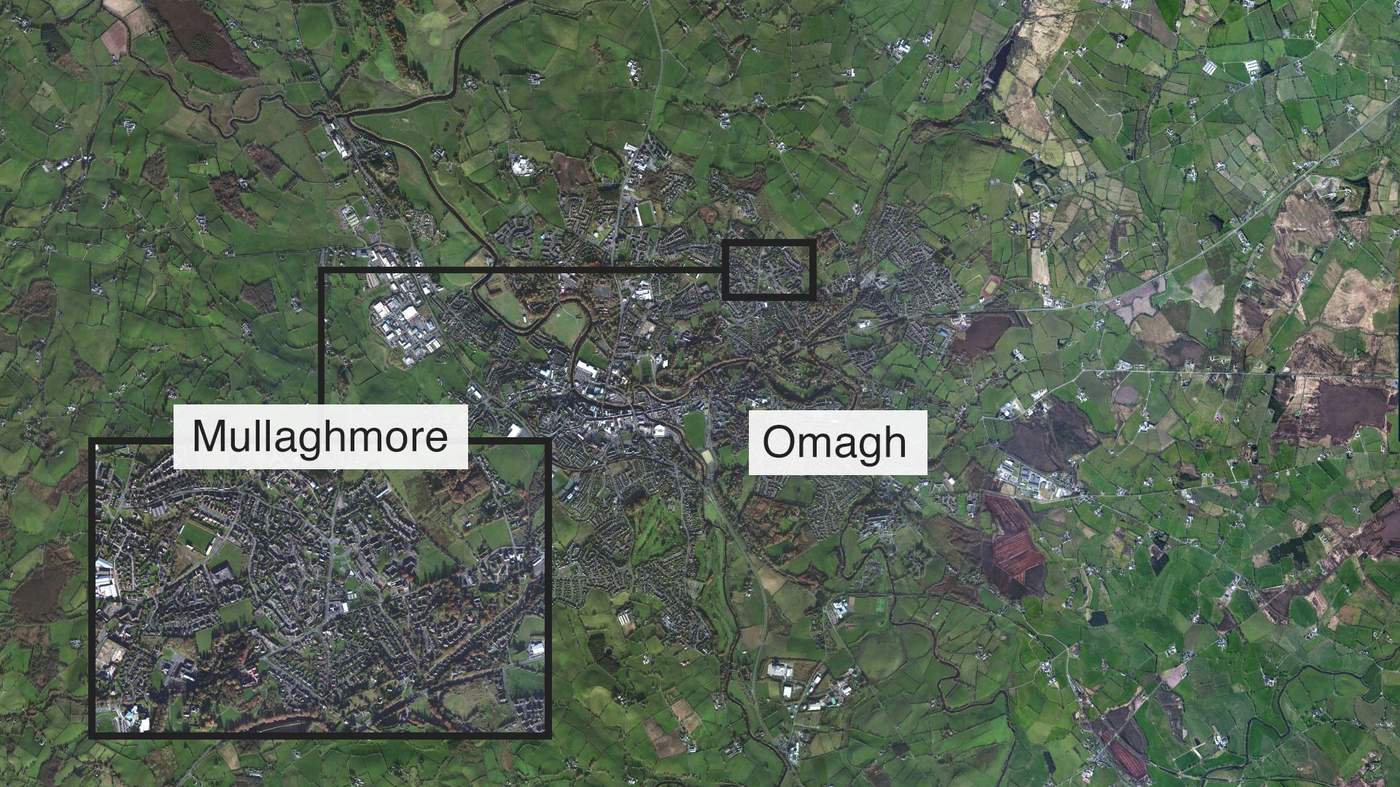

A large H-shaped red metal structure with a sign on the crossbar saying “Welcome to Mullaghmore” announces your arrival.

It’s a network of cul-de-sacs and short dark-brown brick terraces.

It’s easy to get disorientated if you’re not from the area.

This was Noel Knox’s patch.

It’s where he got to know his girlfriends.

He’d grown up here and was living in one of the yellow bungalows at the bottom of the hill in nearby Castleview Court.

There are a lot of steps throughout the estate and from the higher ground you can see down to an electrical substation.

The wind can be biting up at the top.

There’s not much in the way of shelter.

There’s a playground and lots of grassy areas but we didn’t see any children playing there on any of our visits.

In fact, you rarely see anyone.

The first people we encountered were plain-clothed police officers removing evidence bags filled with computer equipment from one of the houses.

We began by trying to find No 61.

A friendly woman going into her home explained that about five years ago a number of abandoned flats on the estate were knocked down.

No 61 was one of them. It has since been replaced by a conservatory and a parking space.

No 61 was divided into two flats, one of which was used by a circle of drinkers from in and around the estate.

They’d gather with their cans and plastic bottles of cider.

In 2002, one of Knox’s girlfriends died the month before her 31st birthday.

Diane Conway's death certificate

Diane Conway died in his arms, he later said.

The mother-of-two lived in a large bungalow, not far from the Mullaghmore estate.

She had increasingly turned to drink after her marriage broke up. Before long, she and Noel Knox were an item.

Things for Diane took a downward turn.

She suffered from epilepsy, apparently made worse by her addiction to alcohol, although she knew when a fit was coming and would call for help.

In the height of summer, she died after a seizure.

Noel Knox was with her.

He didn’t call for help.

He did eventually phone one of her family members, but by the time they arrived, it was too late.

The family got on with life as best they could.

And no one else consideredNoel Knox’s link to the young woman’s death.

Until nine years later.

We can piece together what happened that August evening in 2011 from court transcripts.

The Cellar Bar, Omagh

Noel Knox was drinking at the Cellar Bar, a small place in the centre of the town, close to the river Strule one Friday afternoon.

He was playing pool.

At some point during the evening, 26-year-old Mark McGlone came into the pub.

He played pool with Knox.

They got talking.

The younger man mentioned his dead sister, Diane – he’d been only 18 when she died.

That’s when he found out Noel Knox was the man who’d failed to call for medical help as she was dying.

His defence barrister would later admit McGlone “flipped”.

He went outside, broke a glass and came back into the bar, pinning Noel Knox down and slashing his face and throat.

Knox needed 16 stitches to his throat and 14 to his face.

The barman jumped over the bar, restrained McGlone and heard him say: “That bastard killed my sister… I’d do it again.”

McGlone was charged with attempted murder and later admitted a GBH charge.

The court heard that he was a quiet and private man who’d never been in trouble with the law before.

He was sentenced to five years for the attack – two of which

were to be spent in prison.

A year after Diane Conway’s death in 2002, a woman was found lying at the bottom of a stairway in Mullaghmore with a serious head injury.

In her 50s and part of the circle of drinkers, she has been described as “a big woman” who was kind and confident.

She was known for always wearing Scholl sandals, whatever the weather.

We’ve been told she was found at the foot of the stairs by Noel Knox, which was enough to arouse local suspicion.

Forensic investigators made a full examination of the scene, but never released their findings.

Olive Wiley has a mixture of brisk efficiency and warmth and it’s no surprise to find out she was a nurse.

Now retired, for decades she worked in intensive care at the now closed Tyrone county hospital – including in the dark days after the Omagh bomb.

She’s still dealing with those memories.

Olive has never got over the death of her younger sister Katrina – Reenie to her family – who died in 2006.

The way their large family worked, you looked after the sibling next in line. Katrina was Olive’s responsibility.

And that weighs heavily on her.

Katrina Fulton – her married name – was always a free spirit.

She thought it was funny to keep Olive on her toes, her sister recalls - one time going missing for several weeks until Olive tracked her down.

But the sisters were very close – and Katrina kept in touch with relatives throughout Ireland and England.

“She’d have been able to tell you what anybody was doing and what was happening with their kids,” says Olive.

On the surface, Katrina’s life looked picture perfect.

“Katrina was really, really tidy, her house was absolutely perfect, she just seemed to have her life so under control, her kids were always immaculately dressed.”

But when Katrina’s marriage ended, she turned to alcohol.

Gradually, she became part of the circle of drinkers on the Mullaghmore estate.

Olive would call around to Katrina’s house on the estate regularly, often after a busy shift at the hospital.

After all, she was the sister charged with keeping an eye on Katrina.

She got to know the circle and liked them.

The only one Olive never liked was Noel Knox, who she describes as obnoxious, nasty and rude.

“I hated him,” she says.

“He wasn’t a pleasant person. When you went into the house and there were a number of people there.

He always had to be the dominant person, the person who was speaking the loudest.

Olive and Noel argued.

Whatever the subject, Noel knew better, she says – even when Olive was advising Katrina to take her medication.

Olive would ask him to leave her alone with her sister and Noel would refuse.

Katrina always backed Noel up.

Katrina never admitted to Olive that she was in a relationship with Noel, but her sister is confident she was.

The circle of drinkers fell apart – some died, some went their separate ways, until it was only ever Noel that she saw when she went to Katrina’s house.

Sometimes her sister wouldn’t let her in and would shout out the window that she wasn’t to come in as she would only fight with Noel.

Sometimes Olive was happy enough to leave, knowing Katrina was OK without having got through the door.

Katrina often had bruises, but as a nurse Olive knew she was more prone to them because of her heavy drinking.

She didn’t particularly worry until the hospital phoned her three years before Katrina’s death to say that she had suffered a head injury.

When Olive got there, Katrina was having stitches applied to the wound.

She was drunk and confused and it was not clear what had happened.

As she was being taken to the ward, Katrina’s condition suddenly deteriorated.

She’d had a massive bleed in her brain.

Doctors held out little hope but, miraculously, Olive says, Katrina recovered.

After a week, Katrina returned to her house.

From then on, Olive says Katrina let few people other than Noel into her home.

Katrina thought he looked after her, says Olive.

“He was doing things like getting money out with her bank card and probably buying alcohol for both of them,” she says.

I just think that he bullied her and manipulated her and made her believe that he was the only person that she needed to be around.

Olive still called around but more often than not, her sister wouldn’t let her in.

Olive thinks she was frightened of angering Knox.

One April day in 2006, another relative of Katrina’s went to check on her.

“He came into the house and went up the stairs and walked into the bedroom and Noel Knox was standing there,” says Olive. “As soon as he walked into the bedroom Noel Knox walked out.”

The relative went over to the bed and found Katrina seriously ill, in a semi-conscious state.

He rang Olive.

They couldn’t get an ambulance so she helped him carry Katrina to her car.

As they were putting her in, Noel Knox re-appeared.

“He came slinking around the corner and said: ‘Did I leave my coat in there?’”

He went into the house, got his coat and left without asking how Katrina was.

He never did ask about her condition.

Days later, she died.

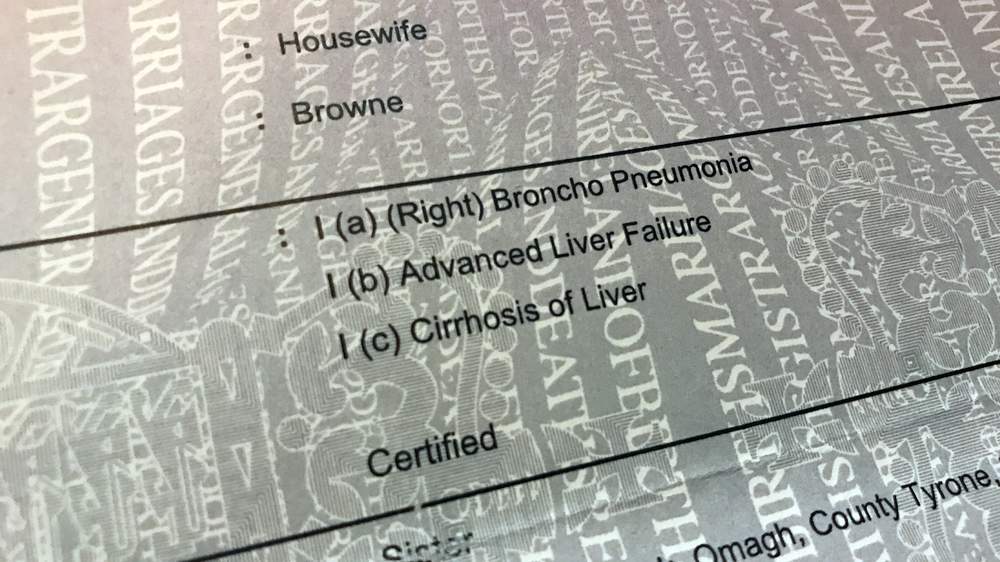

Katrina Fulton's death certificate

Katrina Fulton’s death certificate records her death as due to broncho-pneumonia, caused by advanced liver failure, due to cirrhosis of the liver.

But Olive says her sister seemed normal when she had seen her just a few days earlier.

“I just wonder at that man being in that room and what he could have done to her,” she says.

She can’t understand why Noel Knox didn’t call an ambulance for her sister.

“He wasn’t doing anything, he wasn’t making any attempt to help her, or get help for her, or tell anyone that she was ill.”

She now wishes the police had investigated how Katrina had become so ill, so quickly.

“I think they just assumed it was her alcoholism made her semi-conscious without looking to see if it could have been something different.”

She remembers clearly what a medical professional said to her about the Mullaghmore circle: “It’s just a drinking den, they’re all drinkers and they’re all gradually going to die off.”

Olive questions how fully the authorities investigate the deaths of alcoholics.

Just because they were drunk, doesn’t mean that whatever happened to them just happened out of drunkenness.

That’s something Coroner Joe McCrisken rejects. “It’s never assumed that this is a person who has died because they’ve had a high level of alcohol taken,” he says.

“The fact that someone has chronic alcoholism and a medic or pathologist thinks that is the cause of death, if I think there are other issues around that, I’ll question that.”

Olive is a childhood friend of the journalist Anton McCabe.

After the inquest into the death of Mairéad McCallion in 2017, he put her in touch with Patricia O’Brien.

As they spoke on the phone, the two women noticed striking similarities in their sisters’ relationships with Noel Knox.

They compared how their sisters became isolated from their families, how they were pursued by Knox, how he used to phone or text them “non-stop” when they were away from him.

Patricia recalled her sister, Mairéad.

Mairéad was a smart girl but he had beat her down so much that she thought nobody else loved her and that’s what he was constantly telling her.

Olive spoke about her sister Katrina.

“I believe he was controlling her and anything that happened in her life was directly connected to him.”

It was then that Olive felt she had to speak out about what had happened to Katrina.

Photos of the man some called “Knoxy” show an unremarkable looking man, grey in pallor with the pot belly of a drinker.

While Anton McCabe didn’t know him personally - they went to the same school, but not at the same time - he knew Knox by reputation.

He was known as “a hard man” or “a hood”, he says.

He was somebody not to be messed with, somebody with a degree of menace.

"Many would have said that if you didn’t cross him he was ok.”

Noel Knox died suddenly in November 2017 after phoning an ambulance complaining of breathing difficulties.

On his death certificate, his occupation was listed as “bricklayer”, although for 16 years he cared full-time for his brother Brian, who had MS.

Brian died 18 months before Noel, and the brothers share a grave next to a small church outside Omagh.

Two more brothers and Noel’s father are also buried nearby.

Theirs was a large family, and the nine children were brought up on the Mullaghmore estate, which is where we go looking to find out more about Noel Knox.

We knock on the door of one of his sisters, who says she is glad to have the opportunity to clear her brother’s name.

She asks us not to identify her but brings us into her kitchen and talks at length about the brother to whom she says she was very close.

“It was terrible to read all those lies,” she says.

I knew Noel and there’s no way he abused them. And to class him as a serial killer… they made Noel out to be a monster.

The man described by Olive Wiley bears no relation to the brother she remembers.

Noel was easy-going and he was a very helpful and kind person.

She says he was good company, often cracking jokes and making up funny stories.

She knew all his girlfriends and got on with them, although she says they were all “drinkers” whom she urged him to stay away from.

“He’d say: ‘Oh I know, that’s not the girl for me,’” she recalls.

Noel wasn’t an alcoholic, she says, arguing he couldn’t have been because he had to look after Brian.

Olive Wiley also noticed that Noel didn’t seem to drink as much as the others in the Mullaghmore circle, although both women say he was often the one who would go and buy alcohol.

“Any time they would want anything to drink he would go and get the drink,” says Knox’s sister.

His girlfriends “took advantage” of her brother’s good nature, she says.

“I suppose he would have been lonely as well. They all had drink problems and Noel would take them in and care for them.”

Noel Knox’s sister is clearly angry at Patricia O’Brien and Olive Wiley’s allegations.

She denies Katrina was in a relationship with Noel Knox, saying they were just friends.

She knew Mairéad McCallion well as Noel’s girlfriend and liked her.

Although she was often bruised, that was only because she fell over so much and was so thin, adds Knox’s sister: The injuries had nothing to do with Noel.

His sister couldn’t believe it when Noel was charged with her murder.

She says she accompanied him to the courthouse every day during last autumn’s inquest into Mairéad’s death.

He died weeks after the inquest ended. The media’s representation of him as a serial killer was “part of putting a nail in Noel’s coffin”, she says.

She rejects the suggestion there could have been another side to Noel, a side she didn’t know about.

“I knew all sides of Noel,” she says.

OK, he might get a bit angry and a bit annoyed… but (he) wouldn’t go and lift your head and bang you against the wall.

Noel had another girlfriend before he died, and we track her down to a well-kept semi-detached house in a quiet development in Omagh.

While she says she knew Mairéad well from a support group for alcoholic women, she says Noel was very good to her during the two years they were together.

He was never violent towards her and the allegations against him were unfair, she adds.

She is still close to his family and was set to join them at a Mass on the anniversary of his death on 22 November.

We needed to find out more about the woman found dead on the steps in 2003 – labelled by some as Knox’s second alleged victim.

Several people tell us she was part of Knox’s drinking circle, and Olive Wiley says she saw the woman with Katrina.

But we can find no evidence she was ever in a relationship with Noel Knox; one of her sisters denied she even knew him.

When the woman died, forensic officers investigated the scene and a post-mortem examination was carried out.

Coroner Joe McCrisken says it was clear foul play was not involved in the death: Noel Knox may have discovered her body, but that appears to have just been an unfortunate coincidence.

Omagh is still small enough for most people to know each other.

A conversation with Anton McCabe in a local café is repeatedly interrupted by locals nodding and saying hello to him.

Over a latte the freelance journalist points out those around us and wonders aloud if they could help us build a picture of Noel Knox.

One passer-by went to school with Knox, another’s sister lived next to Knox’s cousin.

“Man May Have Killed Four” was one of the articles Anton wrote at the time of Knox’s death.

The tabloids picked the story up and the “serial killer” title was attached to Noel Knox.

From behind a shaggy beard, Anton describes how Noel and his link to four sudden deaths of women in Omagh had been the talk of the town.

“So much of what was in the rumour mill stood up as true,” he says.

I believe that Noel Knox was Omagh’s serial killer.

He sips his latte.

“I believe it because there was a history of women becoming involved personally with Noel Knox and ending up dead.”

“People felt they had put the pieces together. They were saying that Noel Knox was a serial killer.”

The FBI defines a serial killer as anyone responsible for two deaths.

According to Peter Hepper, professor of psychology at Queens University, Belfast, a more commonly accepted definition is someone who kills three or more people, often with a “cooling-off period in between”.

The timings of Knox’s alleged victims’ deaths – 2002, 2006 and 2014 - certainly point to “cooling-off periods.”

“There is no one profile that says a person is likely to be a serial killer,” he says.

“They can be male, female, 10 years old, up to 60 years old. They can be people in professions, people on the street. Anyone can be a serial killer.

But while the attackers can be very different types of people, their victims tend to fit more of a formula, says Prof Hepper.

“A lot of serial killers target a certain type, so whether it’s male, female, it may be a certain type of hair colour, a certain context.

People who are powerless and who are easier to control are often more likely to become victims.

If anything ties Knox’s victims together, it is their alcoholism and the chaotic lifestyles they led.

Pat Fahy’s legal practice sits in the shadow of Omagh courthouse.

He’s been a solicitor in the town for 48 years.

The McCallions are long-term clients; he knows the family well.

The case of Mairéad McCallion got under his skin, he says, and he was shocked the Public Prosecution Service dropped the murder charge against Noel Knox.

His repeated lobbying on behalf of the family to re-instate the charges was never successful.

After last year’s inquest into Mairéad’s death, the family hoped prosecutors would move to charge Knox.

After all, a coroner had found that the head injury Mairéad had received while being removed from the property at Castleview Court had led to her death.

“There was more than sufficient evidence to mount a case and have the jury decide whether or not Knox was guilty either of murder or manslaughter,” says Pat Fahy.

PPS officials say that at the time of Noel Knox’s death in November 2017, they were still considering the family’s request, but had not received all the relevant documents from the inquest.

They point to “inconclusive” expert medical evidence which made it impossible to ascertain when and how Mairéad McCallion suffered her fatal head injury.

They also point out the higher burden of proof they require – beyond reasonable doubt – compared to a coroner, who makes a finding on the balance of probabilities.

Joe McCrisken has analysed the death certificates of Diane Conway, Katrina Fulton and Mairéad McCallion.

“Looking at the causes of death for all these ladies, chronic alcoholism or some form of alcoholism is there,” he says.

A criminal barrister for 15 years, prosecuting and defending, before he took up his role as coroner, Joe McCrisken says there was nothing in the death certificates to indicate the work of a possible serial killer.

We asked about Knox’s failure to call an ambulance before two of the women died.

“If there were concerns about a failure to seek medical attention and there was good cogent evidence to underpin a request, that’s something that could be considered during an inquest,” he says.

He had held inquests in those circumstances before, he says, adding that the families only needed to write to him to request the deaths of their loved ones be further investigated.

There was no set test he says, in deciding whether to hold an inquest, which must merely be deemed “useful”.

This is not a neat detective story.

PSNI officers looked at Knox’s links to the four dead women in 2014. After a short investigation they concluded there was not enough evidence to press charges.

And since Knox is dead, some of the questions about the women’s deaths can never be answered.

The PPS, police and a coroner may agree that under the current system he had no legal case to answer.

It’s a high bar to prove murder “beyond reasonable doubt”.

As Joe McCrisken put it, you have to be 95% certain.

That is a point that is almost impossible to reach when alcohol is involved: It is a perfect weapon that provides a perfect cover-up.

Many alcoholic women feel too ashamed to ask for support from friends or family, which leaves them particularly vulnerable to abuse.

Alcohol keeps victims compliant. It cuts off avenues of escape - many refuges don’t accept drinkers.

It also changes how they are viewed by those who witness disturbing behaviour.

And if they have been attacked, an alcoholic may struggle to remember, to give a clear account or perhaps even fully understand what has happened.

Prosecutors can be reluctant to take forward cases involving these women, argues Orla Conway of Women’s Aid in Omagh.

Very often just the impact of abuse and trauma means you aren’t able to express yourself in a clear and sequential narrative

and of course that’s what the criminal justice system wants.

Most cruelly of all, perhaps, even though the mind has been compromised, after the event the body can offer little reliable evidence.

Every questionable bruise and injury is contaminated with a suggestion that maybe it was due to “a drunken fall”.

Whether or not Noel Knox is a serial killer, does he bear any responsibility for the women’s deaths?

There are three families who believe he does.

Why didn’t he call an ambulance when Diane Conway was suffering a seizure?

Why was Katrina Fulton in a semi-conscious state – and why wasn’t he helping her?

And why weren’t agencies working together to protect Mairéad McCallion from a man so many thought was dangerous?

Predators can target and abuse vulnerable women, enabling them to drink more alcohol and become increasingly dependent if they become alienated from family and friends.

The reasons for death listed on official records might not suggest foul play, instead referring to issues related to alcoholism.

It doesn’t mean there are no victims.

You can hear more this story on BBC Sounds.

If you’ve been affected by addiction issues, help and support are available. Find out more at BBC Action Line.