Harry Uzoka was a successful model - a hard line of work to stay in. Fashions, for faces as well as clothes, change quickly.

But Harry had lasted the best part of a decade. He had been booked for jobs that black male models had struggled to get in the past.

At 25, he knew he’d had a good run and made a good living, but he was starting to explore the idea of doing something else - writing a film and launching a magazine that would celebrate black excellence.

Life was good. His girlfriend Ruby Campbell was also a model. They had flown to St Lucia for Christmas, the first truly big holiday he’d ever had.

He was building a house for his mother, Josephine, in her home country Nigeria - where she planned to return.

But on Thursday 11 January 2018 all this ended.

Harry lay on the pavement, his body punctured with knife wounds. One was to the heart and the paramedics and doctors couldn’t save him.

At 17:00, on the cold concrete outside his home in Shepherds Bush in west London, he was declared dead.

A confrontation with another male model - lasting just a couple of minutes - had taken everything.

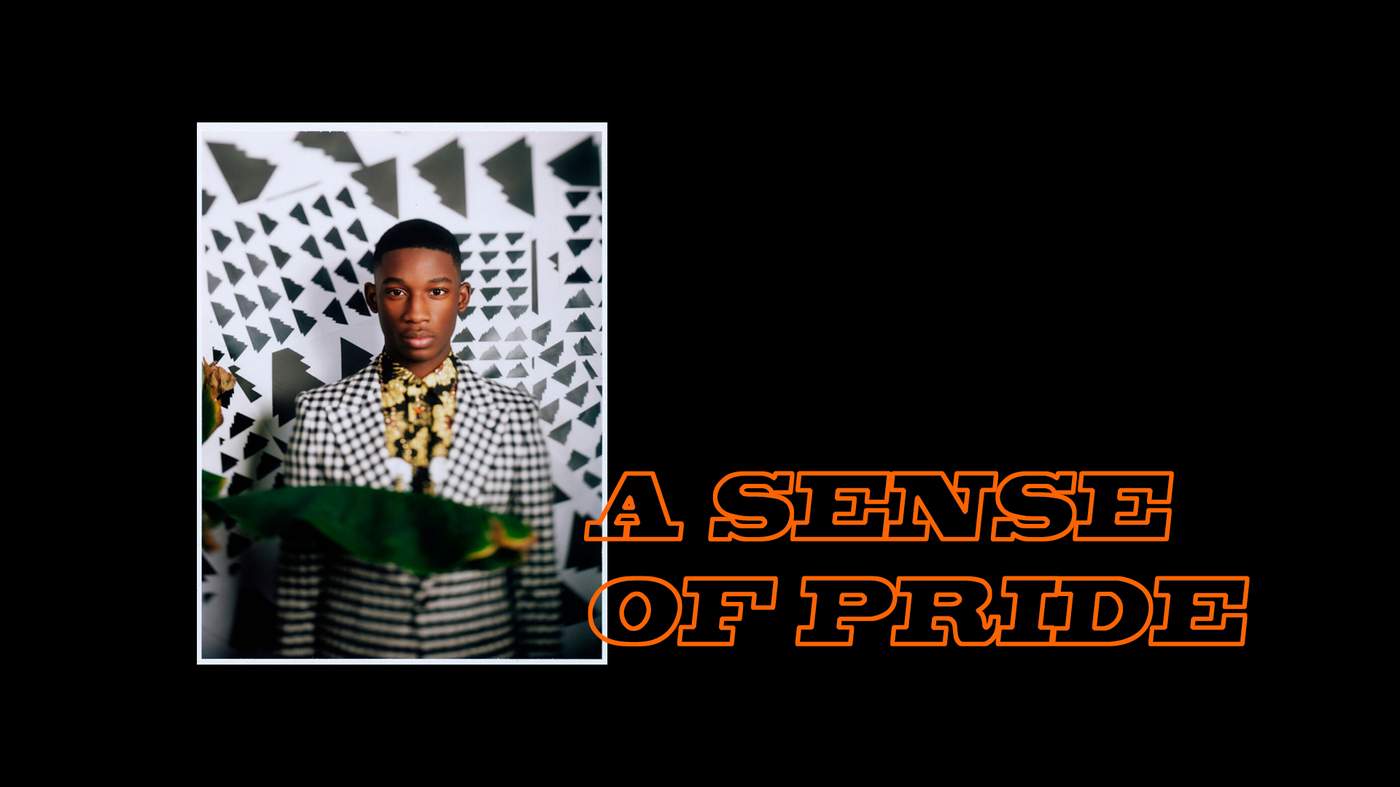

When I was growing up, there didn’t seem to be that many young black role models around.

So just seeing Harry Uzoka’s face in London’s West End on a big advertising board at Oxford Circus would be enough to stir up a sense of pride. There was just something about him.

“Inspirational” is a word that’s been used time and time again to describe him by stylists, agents, photographers and other models.

He was fun, oozed personality, was eager to learn and easy to be around, according to his friends.

Kevin Morosky, a photographer and filmmaker, shot Harry in one of his first editorials. Harry became “the go-to guy”, he says. “He had a massive impact on the way the fashion industry cast dark-skin boys.”

Harry was driven to help others improve themselves - but at one time he had had to turn his own life around.

In 2008 he was sentenced to four years in a young offenders institution for his part in a robbery. He served two years of that sentence.

Childhood friend, Jeremie Thompson, was convicted alongside him.

“We were kids. We looked like kids,” he says. “It was just mixing with the wrong people. They’re not putting the legit ways of having money - it’s just whatever you can do to get it. We fell in to that.”

The pair knew they had done wrong and, as soon as they were inside, Harry’s friend says they were making plans to do something positive once they got out.

“People could just tell we didn’t come across like gang members or anything like that. We always spoke about coming out and going into something big.”

Inside, Harry spent a lot of time reflecting and reading - particularly books about spirituality, according to his friend.

“He got that from his brother. Ed was always talking about things to do with the mind and how powerful your mind is.”

Jeremie now works in marketing for a sportswear firm. He knows the impact his friend had on his future.

Even with his new success Harry never forgot about the people he grew up with, recalls Jeremie Thompson.

“He’d always say if he’s earning money or if he’s doing well, and all his friends aren’t, he’s not doing well.

“I’ve messaged Harry and said, ‘Bro do you think you have five pounds you can send me just so I can get a meal?’. And he’d be like, 'What!’ and come off the phone and send me like £300 and he’d do that without expecting it back.”

Despite this, Harry wasn’t lavish in his own life and rarely went on holiday, although he longed to go to Nigeria and explore his heritage. That was just one of his dreams.

Things came to a head on 11 January 2018.

Seven months later, George Koh, 24, and Merse Dikanda, 24, were convicted of murder. Jonathan Okigbo, 24, was acquitted of murder but convicted of manslaughter. All three had pleaded not guilty at the Old Bailey.

Harry’s housemate Adrian Harper had told the murder trial about the events that led up to the tragedy.

Harry said he had been told by a woman that Koh was claiming to have slept with Harry’s girlfriend, Ruby Campbell.

Harry initially seemed happy to laugh it off, his housemate told the court.

But that wasn’t what happened. The two models exchanged messages.

GEORGE KOH TO HARRY UZOKA

11:42:43 Yooo

11:42:44 G

11:43:54 Why is your boy messaging me

11:44:09 What is he on about & what girl

HARRY UZOKA TO GEORGE KOH

17:24:29 What’s your number?

GEORGE KOH TO HARRY UZOKA

17:48:37 [sends his number]

HARRY UZOKA TO GEORGE KOH

14:21:58 Leave my name out of your mouth, its that simple I’ve never spoken bad of you in any way so this is wild.

Harry’s death hit many people hard - there were hundreds of tributes in the hours and days after.

For some, it’s still difficult to comprehend how a person seen as such a positive force could end up in a such a desperate situation.

Some might think that Harry made a bad decision shortly before his life was taken - but it does not erase the fact that a young man was stabbed to death.

With the recent spate of knife violence in London and other big cities, it’s easy to lose track of the numbers and names, and merge all the headlines into one.

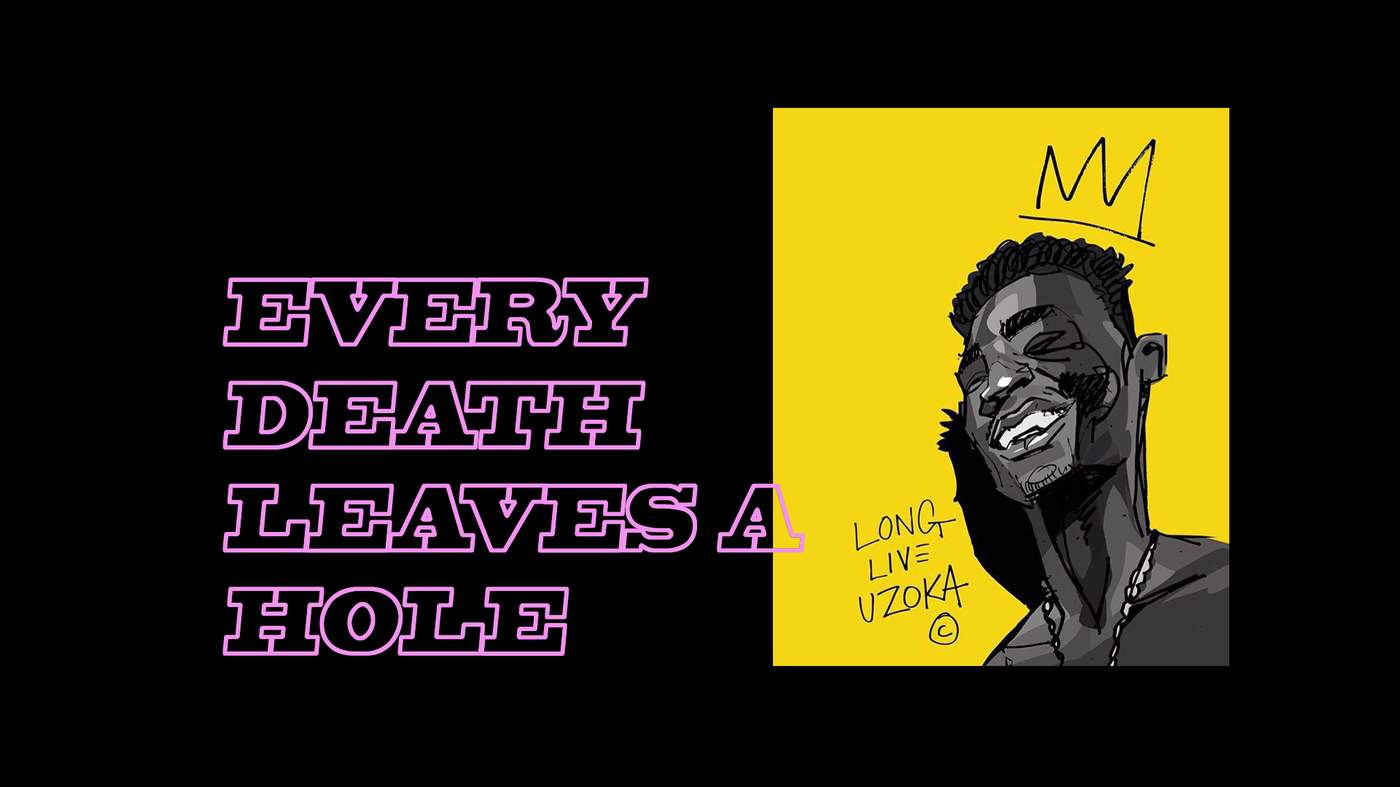

This case stood out. But every victim of knife crime is someone who shouldn’t have died. Everyone was somebody’s child. Every death leaves a hole in a family.

To those who knew him, Harry Uzoka was full of love, and his life was so far away from how it ended.

Lots of people have made the wrong choice at some point in their lives - Harry clearly did as a teenager.

But he made a conscious effort to change.

And he made that transformation look effortless, recalls Jeremy Boateng.

“You know when someone truly transforms? I didn’t know him when he was in jail. When he came out he had a little bit of, like, still that hoodness in him.

“But he was just a young spirit, the second he had removed all that ego from him, completely different guy - it was just love.”

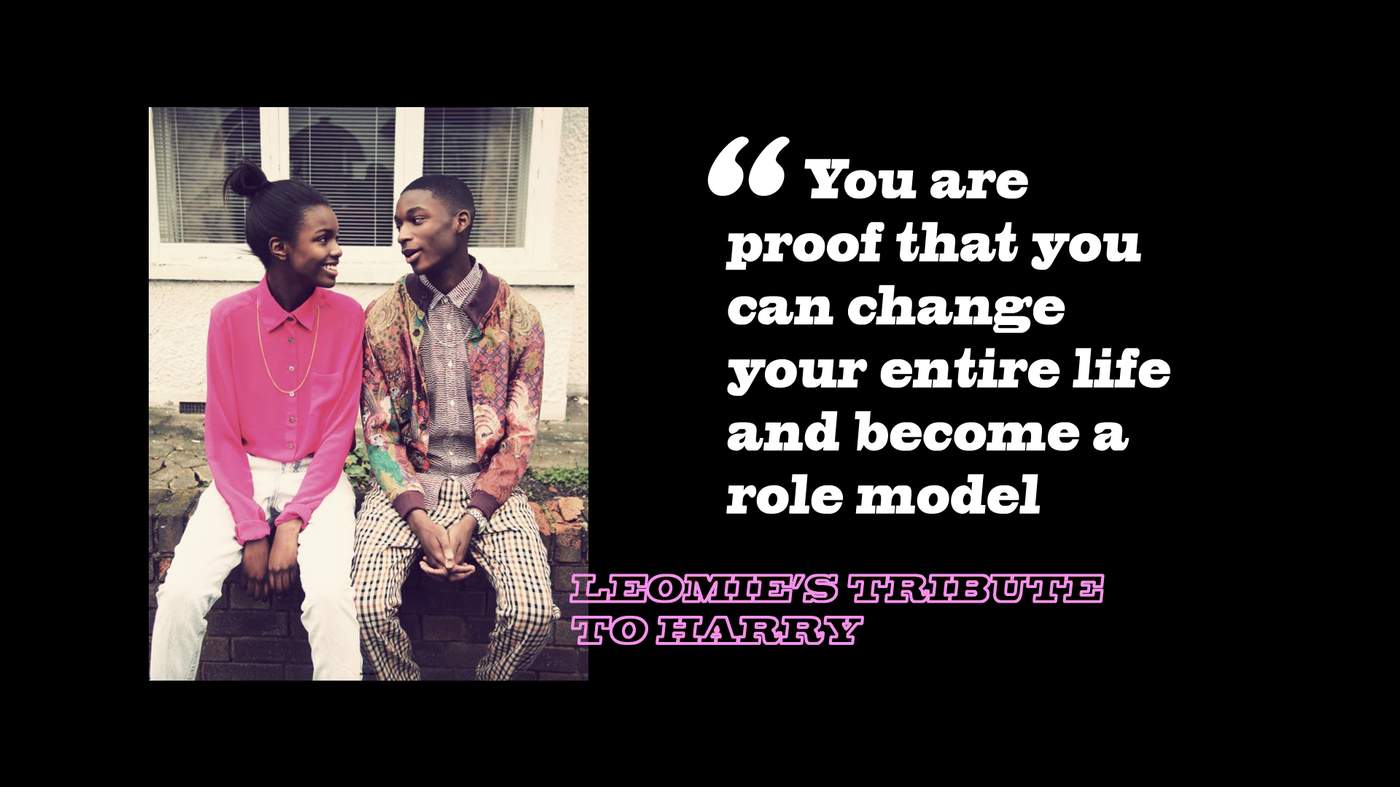

In an Instagram tribute to her former boyfriend, with whom she had remained firm friends, Leomie Anderson wrote: “You’ve been all over the world and been an inspiration to so many. You are proof that you can change your entire life and become a role model, no matter the circumstances.”

Rapper Wretch 32 posted an impassioned reaction on Instagram to the news, pleading for an end to the violence.

After describing Harry as “groundbreaking”, he said: “He’s got nothing to do with nothing… youths start walking around with these mental knives, and you think you can stab people with these knives and they’re going to survive.”

Harry was once asked in an interview how he wanted to be remembered. “More than anything, just honest - an honest being of love and light.”

Words: Linda Adey

with additional reporting by Jeremy Britton and Naomi Pallas

Photography and art: Drew Wheeler, Jeff Hahn, Kevin Morosky, Timo Kerber, Holly Falconer, Clare Shilland, Vicki King, Willprinceart

Editors: Kathryn Westcott and Finlo Rohrer

Production: Naomi Pallas