Warning: This piece contains details of torture and sexual violence that some readers may find upsetting.

It was a family wedding, a happy occasion that was supposed to lift her spirits. Zubeida was badly in need of that.

The 23-year old was an inpatient at a Cairo hospital, being treated for recent traumas.

Her younger brother collected her and they headed for the family’s former home, in a crowded, gritty neighbourhood. Some of her best clothes were still at the old flat.

He rushed to the chemist to fill a prescription for Zubeida, leaving her at the entrance. When he returned, minutes later, his sister was gone.

That was 14:00 on 8 April 2017. She hasn’t been seen since.

The attractive young woman with striking hazel-coloured eyes has joined the ranks of Egypt’s “disappeared”.

The events of that day are recounted by her mother, a welcoming woman in a black abaya and patterned headscarf. She wants to be known only as “Um Zubeida” - meaning Mother of Zubeida.

We meet at the family’s current home, not far from the Pyramids. The flat is sparsely furnished but spotless. It’s in a high-rise block that offers few comforts but does allow anonymity. The family moved here hoping to give Zubeida a fresh start. Instead they lost her.

“I have been trying to find Zubeida for 10 months,” she says, her eyes wet with tears. “Every day I die a hundred times. Our entire family has been destroyed, all six of us - her siblings and me - all destroyed. We wish we were dead.”

Um Zubeyda has not seen her daughter for 10 months

Um Zubeida is in no doubt about who is responsible for her daughter’s disappearance. “We know it’s the police,” she says. “Neighbours told us that armed and masked men came in a police vehicle and took her away in a minibus. They had been to our old house, inquiring about her, several times.”

Zubeida had her brother’s mobile and managed a quick call to a relative, according to her mother. “He could hear the officer insulting her and then the phone was switched off.”

For mother and daughter the trouble started years earlier.

They were just passing by a protest in 2014, says Um Zubeida, and were arrested - in the wrong place at the wrong time.

They were convicted of several offences including attending a banned demonstration. Um Zubeida says they spent seven months in jail but were later acquitted.

Her account of what happened during their initial interrogation is chilling, but all too familiar to lawyers and human rights campaigners in Cairo.

“For 14 hours, they kept beating us, and insulting us,” she says. “They stripped us, and electrocuted us. They wanted us to confess to things that we had not done like planning to blow up a hotel, and having weapons. I heard Zubeida’s voice screaming, ‘help me Mother’. I couldn’t see her but I told her, ‘Don’t be afraid’.”

Um Zubeida says she refused to confess - though they threatened to rape her daughter in front of her.

I found cuts on her body, and marks of electrocution... They had done to her everything that would anger God”

After she and her daughter were released from prison, they tried to rebuild their lives. Zubeida was studying commerce, and dreaming of opening her own small business. She went out to buy shoes on 15 July 2016 and disappeared - for the first time.

“The car she was in was stopped at a police checkpoint,” says Um Zubeida, “And everyone was taken out. She gave my mobile number to a bystander and asked him to call me. By the time I arrived the police had gone.”

Zubeida was dumped by the roadside on the outskirts of the city 28 days later. Her mother describes her daughter's return in a halting voice - as if each word is swollen with pain.

“Someone found her and called us. She was blindfolded and her hands and legs were tied. When we brought her home, her abaya was torn. She had no underwear underneath it. I went with her to the bathroom to help her change and to wash.

“I found cuts on her body, and marks of electrocution. I was shocked when she told me that they assaulted her. They had done to her everything that would anger God. Everything.”

Zubeida was a changed girl - no longer friendly and sociable. “She didn’t want to see people,” her mother says. “She tried to isolate herself. She wasn’t happy like before. She started hiding under the bed, screaming. We had to take her to a psychiatric hospital.”

It was when she left the hospital, for the wedding, that she lost her freedom for the second time.

Her mother now seeks comfort in Zubeida’s bedroom, which is like a shrine. Everything is just as she left it last April, as if the young woman had been gone for a few hours, not almost a year.

Her dresser is lined with treasured keepsakes that might belong to a child - a jewellery box in the shape of a tortoise, cuddly toys and small ceramic cats.

Zubeida stares out serenely from a framed photograph. There’s a whisper of lipstick on her mouth and her hair is concealed beneath a stylish leopard-print headscarf.

The photo was taken just after she and her mother were released from jail in 2014. “She was so happy because they had let us out,” says Um Zubeida. “Unfortunately, the happiness didn’t last.”

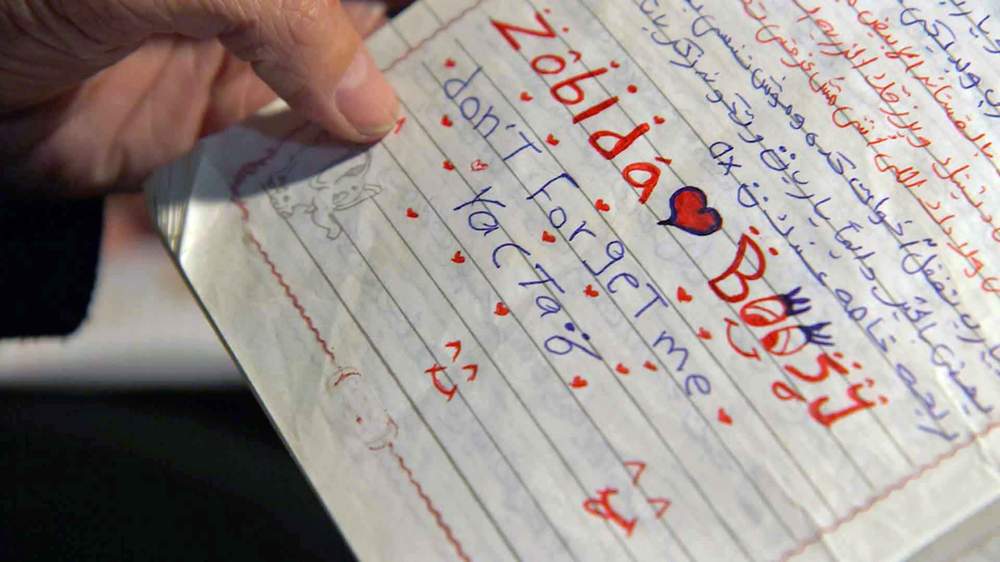

Um Zubeida shows me a jotter full of drawings and Arabic script. It was her daughter’s prison journal. There’s one phrase written at the bottom of a page in English that stands out: “Don’t forget me”.

She insists the family has no connection with any banned groups, including the Muslim Brotherhood. The Islamist movement was branded a terrorist organisation in 2013, after one of its leaders won the presidency but held it for just a year.

Many families of the disappeared - and there are many - are too frightened to speak out. Despite the risks, Um Zubeida refuses to be silenced, even though her daughter has disappeared not once but twice.

“I wish they would take me, and let her go,” she says. “Take me, arrest me instead. What danger might we pose to those in power? If my daughter is disappeared and they’ve taken her and tortured her, how can I not speak out? Even if my words lead to my hanging, I will still speak.”

Does she thinks Zubeida will come back? “I have hope in God Almighty that she will come home,” she says.

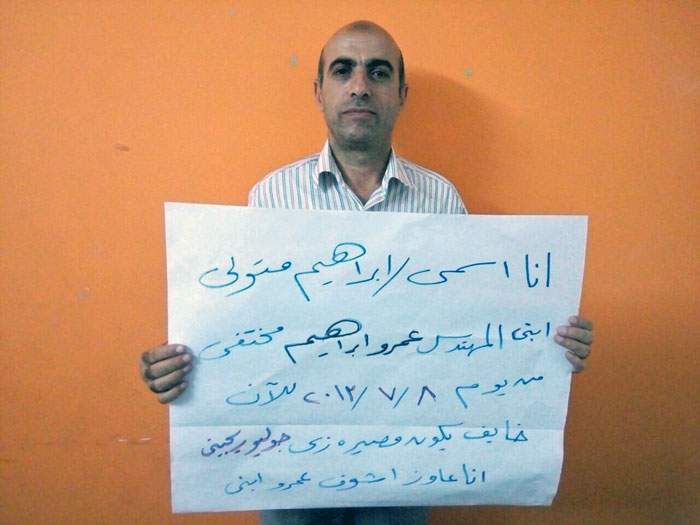

The trip was a risk. Ibrahim Metwaly knew it, and so did his family.

On 10 September last year, the 52-year-old lawyer set out for Cairo International airport to board a morning flight to Switzerland. He was due to testify before a United Nations working group on enforced disappearances.

For Metwaly it was personal - his eldest son, Amr, had vanished more than four years earlier.

Ibrahim Metwaly

“My mother told him not to travel,” says Abdel Moneim, his youngest son, “because she could not bear anything else. But he had made up his mind. When a son is in danger, a father will do anything.”

During the day Metwaly’s family got a text - from his phone - saying he had left for Geneva, and heaved a sigh of relief.

The message did not come from Ibrahim. He had joined the ranks of the disappeared, or as Egyptians say, those “hidden behind the sun”.

Ibrahim Metwaly’s disappearance made headlines abroad. Two days later, amid growing international pressure, he was produced in front of prosecutors. He was charged with “spreading false news” and “forming an illegal organisation”.

That referred to a support group for families of the disappeared which he co-founded. Metwaly gave advice and legal assistance to many desperate families. Zubeida’s mother had turned to him for help as she went from one police station to another, begging for information about her daughter.

If Metwaly had made it to Geneva he was planning to raise the case of Giulio Regeni, a murdered Italian doctorate student.

Regeni vanished from the streets of Cairo in January 2016. His mutilated body was found in a ditch on the outskirts of the city. Zubeida was later dumped near the same spot.

His corpse bore the hallmarks of torture inflicted by a professional. Metwaly had been investigating his killing.

Giulio Regeni, an Italian student tortured and murdered in Cairo

“My father wanted to protect the remaining young people whose lives were in danger,” says Abdel Moneim, a law student. “He saw himself as a father to all of them.”

It now falls to the 22-year-old to speak for him, though he knows he could be next. “I am worried. If I disappear my future will be lost. But I am not doing anything illegal - just being my father’s voice.”

The Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms has documented at least 1,500 enforced disappearances in the past four years, but some believe the real figure is much higher. In the words of a leading campaigner, Mohamed Lotfy, “making people disappear is a hallmark of the regime of President Abdul Fattah al-Sisi”.

Anyone who opposes the regime, or is suspected of doing so, whether rightly or wrongly, is at risk. Sometimes even relatives and friends of suspects can be arrested. Many of the targets are Islamists - people who believe Islamic principles should shape society and the political system. In Egypt, most don’t call for the use of violence to achieve their aims.

Campaigners say most of the disappeared are tortured before reappearing in custody weeks or months later, facing terrorism charges.

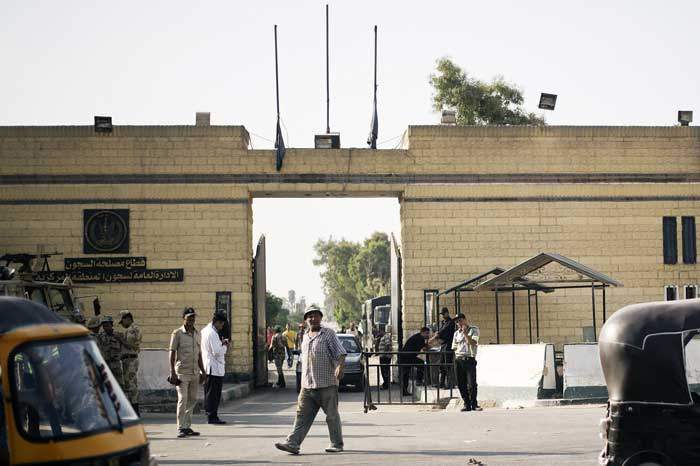

He knows where his father is, though the knowledge brings little comfort. The human rights lawyer is now a prisoner in Cairo’s notorious Tora prison complex. “He is being held in solitary confinement, in a dark cell,” says Abdel Moneim.

“He is getting a very small amount of food - not enough for a 10-year-old child. He found a rat in his cell and had to kill it. We have only been allowed to visit him once, for three minutes. He is in poor health and the way he is being treated is putting his life in danger.”

He says the prison routine involves not just hardship and hunger, but also torture. “My father was electrocuted,” says Abdel Moneim. “He was stripped and he was beaten. He documented the violations when he appeared before the prosecutor.”

Lawyers, human rights campaigners and former prisoners in Egypt say this kind of brutality is now routine. As one lawyer put it: “Torture is a must.”

Mahmud Mohamed Hussein has first-hand knowledge of current torture techniques. He’s a slight 22-year-old in a hooded top and skinny jeans. Every step he takes is a reminder of the abuse he suffered. One of his legs is badly bowed.

Mahmud was arrested in 2014 - on the third anniversary of the revolution. He was just 18 and had gone out to celebrate. He says he was detained, and persecuted, only because of the slogan on his T-shirt.

It read: “A nation without torture.”

Mahmoud after his arrest in 2014

“They deliberately beat my bad leg - which was already injured,” he says. “They hurt me so badly that I could only walk with a stick until a few months ago. And since then I’ve had several operations.”

But the beatings were just the beginning.

“I was electrocuted in sensitive parts of my body,” he says, gesturing towards his groin. “I was in terrible pain. What happened can never be erased from my memory. I suffer very badly from nightmares.”

Mahmud was held for more than two years without trial. He is speaking out in spite of the risks for the sake of many other victims, including some of his relatives and friends.

“There are many people suffering what I have been through,” he says. “I saw many people in prison who asked me to convey messages about what they faced. I can only stop talking about torture when it comes to an end.”

Mahmud: “I can only stop talking about torture when it comes to an end”

Mahmud is not the only torture victim to share his story with me. Another young man - who asked us not to reveal his identity - described being subjected to every kind of abuse.

He provided a detailed and credible account identifying the police station where he was interrogated. He said he was blindfolded, stripped, beaten, kicked and given electric shocks. Then - in his words - he found out there was something worse than electrocution. He was raped - with a stick.

For Manal Hussein and her six-year-old son Khaled, quality time comes once every 15 days - with a visit to a prison complex. That’s where they are reunited with Alaa Abdel Fattah - the husband and father who is the missing piece of this fractured family.

The 36-year-old is one of Egypt’s leading dissidents - charismatic, secular, a blogger and software developer.

In the heady days of 2011 he was an icon of the revolution. In the Egypt of today that makes him an enemy of the state. Other leaders of the uprising have also been jailed, or driven into exile - erased from view, like the revolution itself.

Alaa Abdel Fattah pictured in 2011

Mother and son set off in bright sunshine. Manal is smartly dressed in a black jacket, trousers and boots. Her patterned sweater has an owl on the front. She brings food parcels, fresh laundry and cigarettes. Her husband doesn’t smoke, but tobacco is the currency in prison. Khaled darts along beside her - a blur in a bright blue sweatshirt.

I join them for the journey through the choking Cairo traffic. There is a driver behind the wheel so Manal can sit in the back and focus on her son. He bounces in and out of her arms, smiling but silent. The little boy does not speak yet.

“That’s one of the problems of Alaa being in prison,” Manal says. “I don't know if Khaled has any memory of his father out of prison. Alaa has spent almost four years in jail. That’s more than half his age.”

Her husband was accused of organising a protest against the use of military courts for civilians’ trials. That was in November 2013, just after demonstrations had effectively been banned.

Others came forward to say they had planned the protest - including Alaa’s own sister, Mona Seif. He was convicted anyway.

For Manal the uprising of seven years ago is now firmly in the rearview mirror. “There were a lot of possibilities,” she says. “A lot of plans and dreams, and things to do. Now it’s just, ‘Let’s live the day today, and try to survive that’.”

When we arrive at Tora prison, Manal and Khaled join a queue of families waiting beneath the watchtowers for a chance to see their loved ones.

The gates of Cairo's Tora prison

Afterwards she says the visit was rushed, as usual. “It's very cruel for Khaled because he gets very little time with his father and doesn’t have all his attention. We have to do everything in just 60 minutes.”

Resistance runs in her husband’s family. Alaa’s father was the renowned human rights lawyer Ahmed Seif Al Islam. When he was on his deathbed in 2014 both Alaa and his sister Sana’a were behind bars. They were allowed out only to bury him.

Their mother, Laila Soueif, has been an activist for decades. The extended family gather for lunch at her book-filled Cairo flat.

Laila - a mathematics professor with a shock of grey hair - is busy in the kitchen. She’s chopping salad and frying thin slices of basterma - the spiced beef beloved of many Egyptians.

Several generations gather in the dining room, their voices overlapping in a tapestry of laughter and shared history. But the empty space at the table is keenly felt.

“We are sad. We are sorry. We are unhappy,” says Alaa’s aunt, Ahdaf Souief. “But I think that the anger is really paramount.”

She is quick to stress they are better off than other families whose sons and daughters have been given life sentences, have vanished, or have been killed.

Ahdaf is animated and articulate, with shoulder-length dark hair, and black-rimmed glasses. She chooses her words with care, like the novelist she is. Her eyes brim with tears when she speaks of her nephew. “This is somebody who could have been amazing, and not just for this country. This is somebody with a really valuable mind and set of skills,” she says. “And it's because of that that he's been put away and deactivated. They wanted him out of the picture.”

A whole generation has been crushed, according to Alaa’s sister Mona. The 31-year-old is cut from the same cloth as her brother - the same curly hair, the same commitment to change.

So many of her friends are in prison she struggles to keep count. She says that under President Abdul Fattah al-Sisi, Egypt is bleeding.

“I've never seen a regime as bloody as Sisi’s regime,” she says. “I have never seen a regime that belittles the value of life like Sisi’s regime.”

Mona Seif: “I have never seen a regime that belittles the value of life like Sisi’s regime”

Disappearances, death sentences, and torture have become daily news, she says. “Even people who are silent or are trying to stay away from engaging with the political scene are still being thrown in jail or getting randomly detained.”

She says Egyptians are feeling “numb, exhausted and scared” and there's no fight left on the streets. “It's very understandable to be scared with a regime that is not hesitant about using killing.”

After her brother finishes his five-year sentence next March, he will be on probation for a further five years. That may amount to another form of imprisonment. He could be required to sleep at his local police station every night. That has been the fate of other activists.

Alaa was temporarily released in 2014 to attend his father's funeral

Before Alaa Abdel Fattah was convicted, I met him at his mother’s apartment. It was 2014 and he was out on bail. He and Laila chatted and laughed over tea, the conversation ranging from mathematical theories to political strategies. The young revolutionary was clear-eyed about how much worse things were since the revolution.

“When you were confronting Mubarak hope was a material thing,” he said. “You could almost touch it. And so it was very easy to feel that it was worth it. And so people were taking these risks without any kind of despair. Right now it’s very bleak.”

His late father had spoken - with regret - of bequeathing him a jail cell. I asked Alaa what he thought he would leave his son, Khaled. “Almost certainly a prison cell,” he replied. “And I cannot guarantee in any way that he would not be killed by the police, or tortured by the police or broken by the police. I have no hope of offering my son anything unless we change this country.”

Now it’s a place to take selfies. It’s on the tourist trail for foreign visitors - the Pyramids, the Egypt Museum in downtown Cairo and, just a few minutes walk away, Tahrir (or Liberation) Square.

Egyptians also come to the centre of the square - from shy young couples to boisterous teenagers. They stand in front of a large monument, topped by the Egyptian flag, or sit for a moment on the steps.

They are lured here by memory, not by banners or billboards. The monument is bare. There is no mention of the more than 800 people killed in the struggle for freedom in Egypt - no names, no photographs, no tributes.

In fact there is nothing to indicate that Tahrir was the cradle - and crucible - of a revolution. The busy plaza has long since been reclaimed by the twin constants of Egyptian life - the traffic and the police (those in uniforms, and their ubiquitous colleagues in plain clothes).

If Tahrir sends any message today the regime would like it to be: “Nothing to see here.”

Yet this was where Egyptians converged in January 2011, as calls for change built to a crescendo in the Middle East. It was the early days of the so-called Arab Spring. Given what came later, “Spring” seems a tragic misnomer.

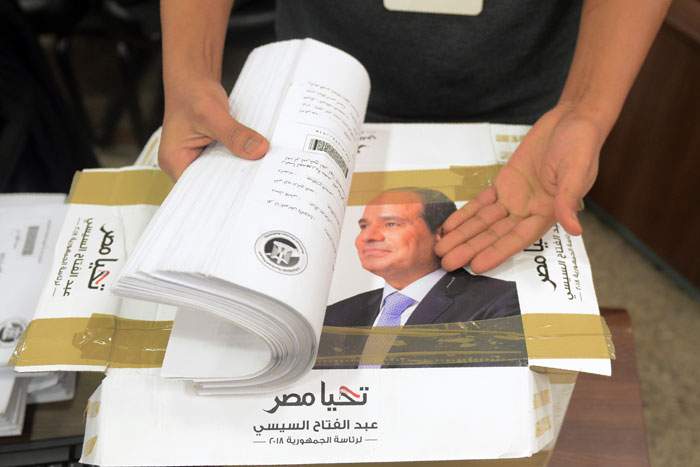

General Sisi, later promoted to field marshal, went on to be elected president in 2014. It was a landslide victory marred by a low turnout.

Critics accuse Egypt’s latest military strongman of an unprecedented assault on human rights.

During my four years as the BBC’s Egypt correspondent I’ve witnessed the security forces turn their guns on peaceful demonstrators.

It was the anniversary of the revolution in 2014. We had just arrived at a peaceful protest when heavily armed police pulled up, wearing balaclavas.

Without warning they opened fire in the direction of the crowd.

I’ve seen unarmed liberal protesters jailed for years. I’ve covered mass trials for Islamists, where death sentences were recommended for almost 700 men - after a hearing that was over in hours.

My BBC colleagues and I have been harassed on the streets by the security forces. A police officer once threatened to shoot us if we did not stop filming.

On another occasion we were detained for filming an interview with a woman whose husband was killed at Rabaa mosque. After a few hours at a police station we were released unharmed, with our interviewee. It was a very small taste from the menu of repression here.

Press freedom is under attack. Egypt is in the top three worldwide for jailing journalists.

Anyone who challenges the official line can be detained for “spreading false news”. Hundreds of websites have been banned - including independent news sites.

It’s not the new Egypt many yearned for when they filled Tahrir Square.

We wanted to get the government’s response to allegations of widespread human rights abuses, and to the accounts we have gathered of disappearances and torture by the security forces. We approached the Interior Ministry, the Foreign Ministry and the State Information Service. No-one was prepared to be interviewed.

In the past officials have denied there are enforced disappearances and widespread human rights abuses. They have told me there is no systematic torture but if “mistakes” are made, officers are punished.

President Sisi seems to regard geography as an excuse. “When it comes to human rights… we are not in Europe. We are in a different region,” he said last October. He also claimed information from rights groups could not be trusted.

Take a stroll through the streets here, past the bread ovens and tea carts and cafes with water pipes and you’ll hear noisy complaints.

There are gripes about broken pavements and soaring inflation - about 17% in January - but you won’t find a clamour for democratic reform.

Many are more concerned about high prices than repression. Plenty of Egyptians are grateful for relative stability under their hardline leader, especially amid bomb attacks by the local branch of the Islamic State group, based in the Sinai Peninsula.

President Sisi still has a bedrock of support, but some who voted for him last time are rueing their choice, posting on Facebook: “I am sorry I elected a dictator.”

As for the international community many are turning a blind eye to the president’s human rights record because he is seen as a valued partner in the fight against extremism.

Before General Sisi was elected president I asked one liberal activist for his prediction. “He will be our Pinochet,” he said, referring to the Chilean general-turned-dictator. “And he will build a lot more jails.”

Human rights campaigners say that - at the last count - 17 new prisons have been built in the Sisi era. The Arabic Network for Human Rights Information, an Egypt-based group, estimates as many as 60,000 people have become political prisoners.

Humour flows through Egypt like the Nile. It’s woven into the DNA of a great nation that has both suffered and endured. The forthcoming presidential poll is providing fresh material.

“Have you heard the latest?” asked a friend. “The presidential election has now dropped out of the presidential election.” The ballot, on 26-28 March, has been dubbed a contest between Sisi and his shadow.

Serious opponents have been disqualified, detained or have dropped out of the race. When the former army chief of staff Lt Gen Sami Anan declared his candidacy he was promptly arrested. He has been accused of running for office without the permission of the military.

One of Anan’s key backers - Egypt’s former anti-corruption chief Hisham Genena - was attacked and badly wounded outside his home. His family said it was an attempt on his life. He, too, was later arrested.

President Sisi will have one “challenger” at the polls – an obscure centrist politician called Mousa Mostafa Mousa. He denies mounting a sham campaign at the behest of the regime, though he’s known to be a Sisi supporter.

While the president’s victory is guaranteed, critics say his legitimacy will be seriously undermined.

Fourteen human rights groups, both international and domestic, have denounced the election as “farcical”. Opposition leaders in Egypt have called for a boycott.

The president seems deaf to his critics - increasingly so. He is adamant that he will not go the way of Hosni Mubarak. “Be warned,” he said recently. “What happened seven or eight years ago will not happen again.”

His nation is grappling with an unstable neighbour (Libya) and a stubborn enemy (IS militants based in northern Sinai). The Egyptian leader presents himself as a bulwark against instability. He says he’s waging war on terror. Human rights groups say he’s using that as a pretext to wage war on dissent.

Instead of a vibrant new democracy in the heart of the Arab world there is a return to the default setting - fear.

In recent years the authorities in Cairo had paid lip service to the need to break with the past and respect individual rights. Now it feels like the mask isn’t just slipping, but being cast aside. That’s a risky strategy.

“They think that through repression and draconian laws they can get what they want – namely staying in power,” says the seasoned human rights campaigner Mohammed Lotfy. “But what this does is to radicalise people even more against the regime.”

Before leaving Egypt in late January, I went to the outskirts of Cairo to take a final trip across the Nile.

Along the way I passed a shepherd tending his flock, framed by lofty palm trees. His little boy wore a traditional long gown - a galabeya - and stood cradling a lamb, not a smartphone.

It was like a scene from centuries ago. In many ways this country of 100 million, with its teeming young population - so full of potential - seems locked in the past.

I boarded the ferry along with a gaggle of passengers in cars, on motorbikes, and on donkey carts. There was surprise at the presence of a foreign visitor - a rarer sight these days. There were shouts of “Welcome”.

A vegetable seller pressed sweet cherry tomatoes into my hand. The ferry captain asked if I wanted to take photos from his vantage point high above the deck. This was a slice of the Egypt I will miss - warm-hearted, chaotic, and rich in spirit.

I have come away, after four years, with plenty of questions. What lies ahead if Egypt can’t steer a course towards real democracy? How many prisons is the regime going to fill? And just how long will it be before all the repression backfires?