Dressed only in their nighties, three girls climb through the unlocked toilet window of an imposing Victorian mansion and make their way silently across the immaculate lawn.

At the wrought iron gates of Lagarie Children's Home in Rhu, the Montgomery sisters stop briefly and look back at the place which had become their prison.

Any second thoughts about escaping are quickly banished as they close the gates behind them and set off barefoot down the road, guided only by the light of the moon.

I’m running away. You’re coming too

For middle sister Angela, 10, the building she knows as home reminds her of an asylum. It is big, old and scary-looking, especially at night time. She’ll be glad to see the back of it, though at this point she doesn’t really know why they are running away, or what they are running from.

Eldest sister Mary, at 11, knows only too well.

On the night of their escape, Mary rouses Angela, and youngest sister, Norma, nine. “I’m running away. You’re coming too. Let’s go.”

The Montgomery plan, although somewhat ambitious, is perfectly formed. They are going to walk for about a mile towards the picturesque Rhu marina, on the banks of Gareloch.

From there they will steal a boat and row it to Brazil, where they believe their merchant seaman father is working. Simple. They know where Brazil is because they have seen it on a map.

Mary decides not to take their little brothers, on account of them being too small.

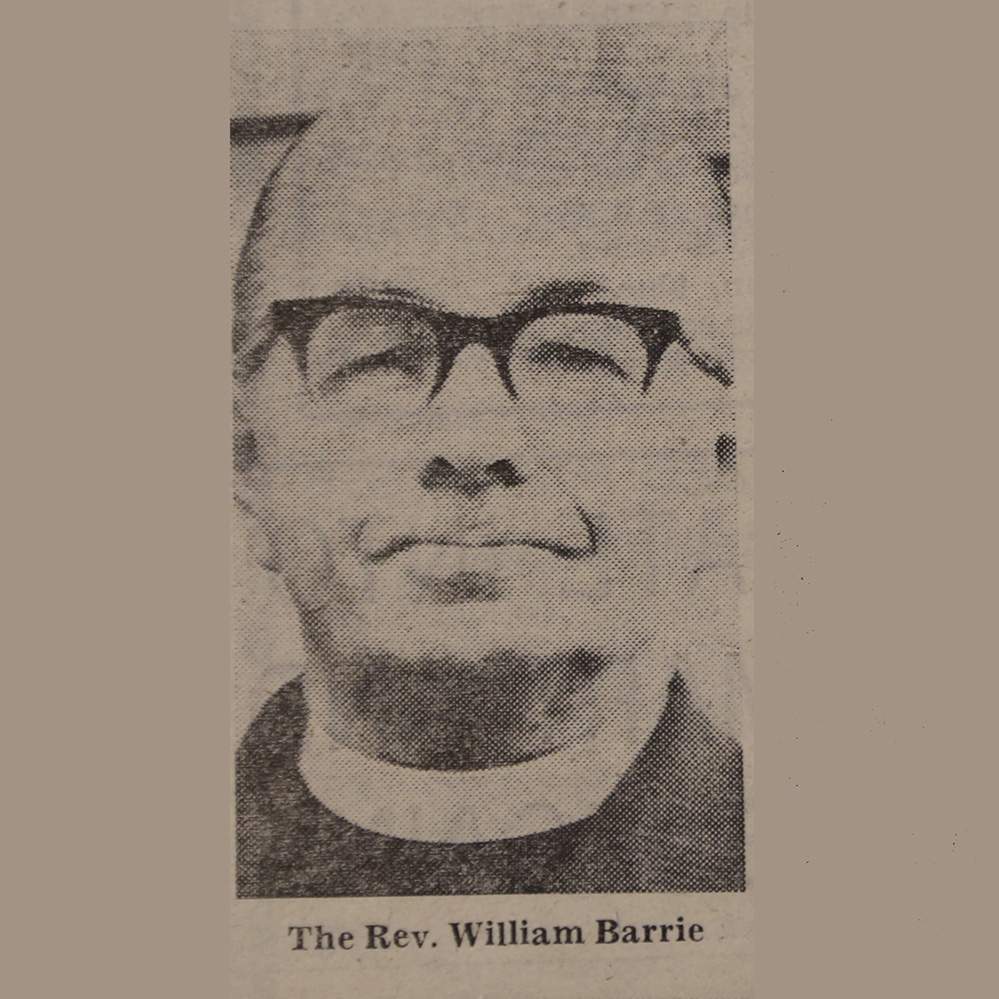

Mr Barrie’s hurting me

At the marina, they find a leaky rowing boat and struggle a few hundred yards out to sea. Shivering and scared, they are eventually rescued and taken to the police station.

“I don’t want to go back there,” Mary pleads with the officer. “Mr Barrie’s hurting me.” Her pleas fall on deaf ears, and not for the last time.

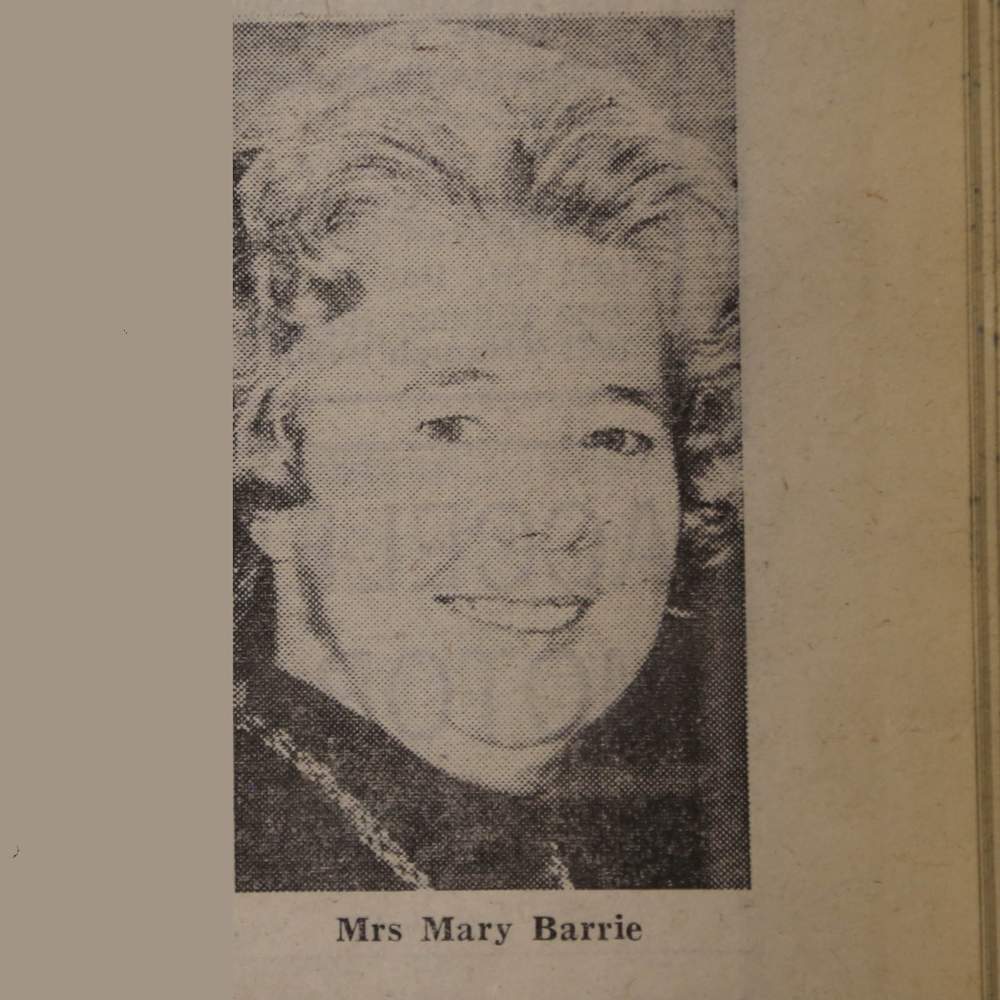

Heather Le Sommer, who worked at Lagarie in the early 1970s, said she noticed the change right away, seeing first-hand how violent Mrs Barrie could be when she assaulted a 10-year-old boy for making a mess in the corridor.

Heather said, “Mrs Barrie came flying through a swing-door to my right, came up to this child and full force cracked him twice right down from the side of his face. I felt physically sick.”

Heather left six months after the Barries arrived.

She says: “I couldn’t stay there. But I had no idea what lay in store for those children.”

Angela recounts: “The level of cruelty we were subjected to on a daily basis went way beyond the boundaries. She [Mrs Barrie] could have you on your bed, face in your pillow, pants whipped around your ankles, hands held together and pressed against your back, before you had time to blink. Then - in one deft movement - she’d remove her scholl, and several whacks later; your arse was glowing.

“When I wet the bed, she’d drag me through the corridors by the hair. I would pull down on her wrists to lessen my weight, fearing I was going to be scalped if I didn’t. The pain was horrendous. If I screamed, if I tried to fight back, this only fuelled her anger even more and she’d start punching me, kicking me, biting me. It was absolutely crazy.”

Angela

More than a dozen former residents and staff claimed Mrs Barrie was a cruel, violent tyrant who spared few her wrath.

She would seek to punish and humiliate the children, especially those who were prone to bed-wetting, an indication, often, of childhood anxiety.

Even the youngest of Mrs Barrie’s charges were not spared, according to Anne Munro, another former worker, who recalls the beatings meted out to a three-year-old girl.

“She was leathered if she wet herself. Three years of age, there was no need for it. And I’m not talking about once a day, it was about three or four times a day with that one child.

“I never thought of intervening, I just stood there and watched her.” On reflection, this makes her feel “terrible,” she says. “I was only 17 at the time”.

According to some accounts, Mrs Barrie reserved her worst for the older girls.

Mary believes she knows why. “She must have known what her husband was doing. He was getting up out of bed at night to come into the home, into our room, to take one of us. She knew all right.”

Angela says: “I remember one night he’d woken me up, took my hand and led me into the laundry room. He unzipped his trousers, shoved me onto my knees, and… I won’t say anymore.

“And when he was finished, he threw me aside. And I remember, because I’d peed myself, and I was lying on the floor, and he said I was disgusting.

“And I still couldn’t move, and then he just left. Nothing like that had ever happened before. I didn’t know that someone was supposed to do that to you.

“I didn’t want to tell Norma and Mary, because I felt embarrassed, because I didn’t know how to describe it. So I didn’t say.”

“He’d work his way around,” Angela says. “I remember several times seeing Norma going out, or Mary. In fact on one occasion, Mary moaned at me, and said, ‘Well, it is your turn, because I did it last night’.

“After a while, even as unpleasant as it was - not that you got used to it - you just thought there was no point struggling or fighting. It became part and parcel of life at Lagarie.”

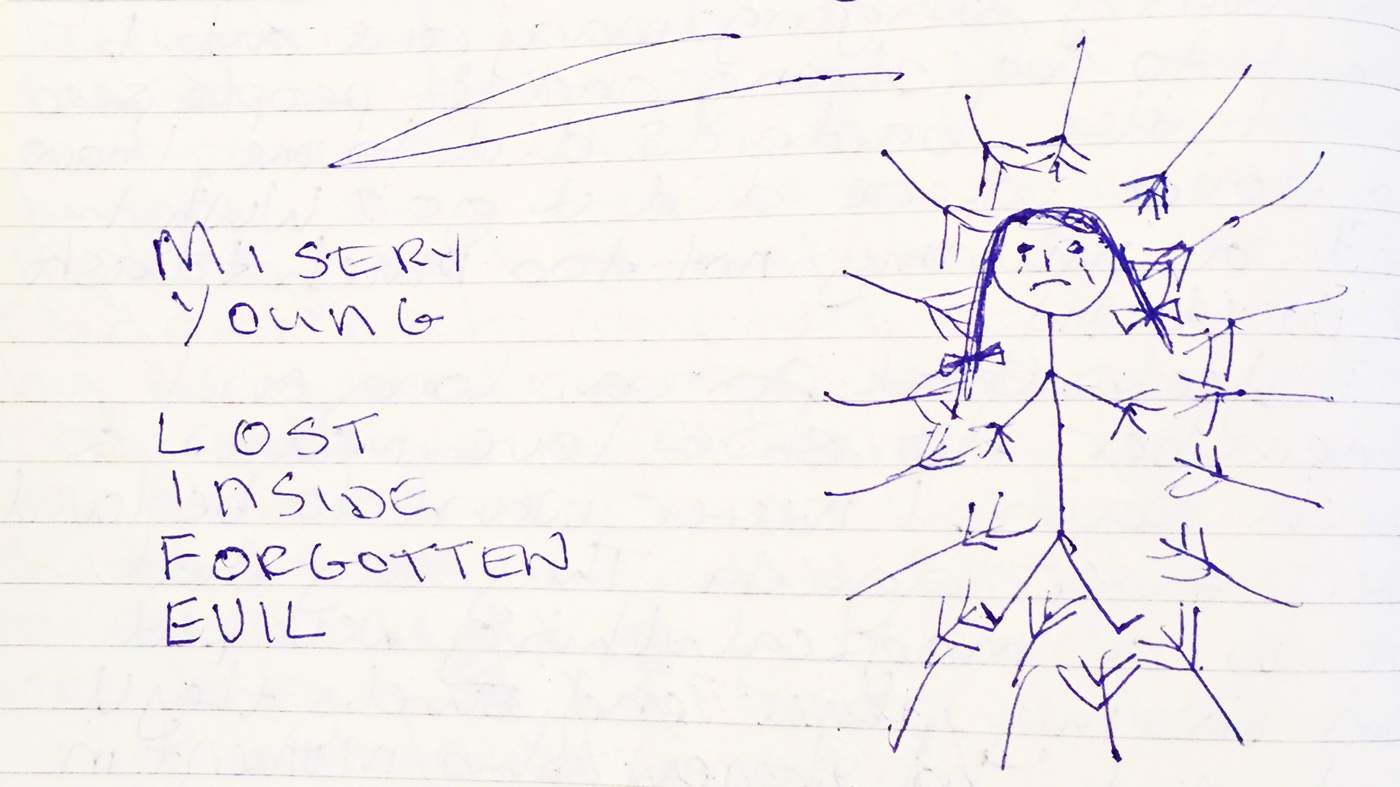

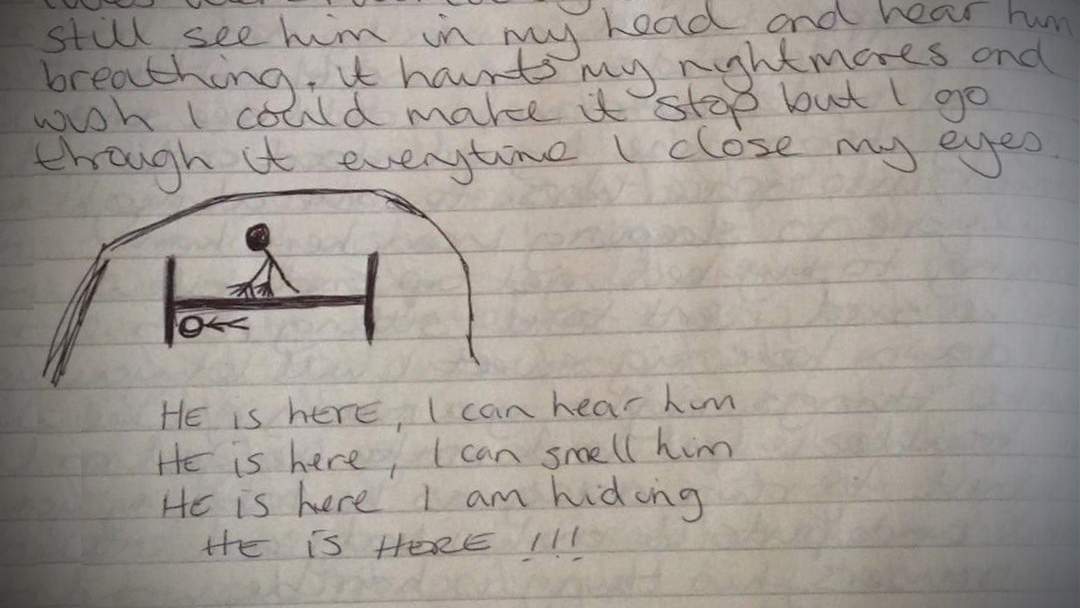

Mary would later write about her memories and draw pictures. The drawings and poems are child-like, visceral, and unbearably sad.

“He is here, I can hear him.

“He is here, I can smell him.

“He is here, I am hiding.

“He is here!”

Norma

The sisters would lie in bed at night, dreading the sound of Mr Barrie’s approach.

His footsteps would crunch on the gravel between his cottage and the big house, and then his hand would turn the handle to their door.

Whose turn would it be tonight?

Every year, the Barries would take the children on holiday to the Arbroath Convention, which was a religious festival held annually.

Angela and Norma had hoped it might be a holiday in every sense.

“We thought he might have left us alone,” says Angela. But he didn’t, she says, and neither did his friends from the British Sailors’ Society.

Both Norma and Angela separately describe nearly identical, multiple attacks, involving a man associated with the society, whom they believed to be a chaplain.

“I liked him. He’d ask me to put Bibles out. He seemed really friendly. Then one day he followed me into the toilet,” says Angela.

She knew what had happened to me. She said nothing

In her front room in Helensburgh, less than two miles from Rhu, Norma, with one of her beloved cats by her side, talks about the man.

She knew him only by his surname, the name he used from the pulpit, when invited to speak at services by Mr Barrie.

Norma says that in the toilets of the Baptist church, close to where they were holidaying and minutes after giving a sermon, the man followed her in and raped her.

“Mrs Barrie was there when I came out, and it was one of the rare times she was nice to me. I was sobbing, and she helped me clean up. She knew what had happened to me. She said nothing.”

After the telling of this story, the cat looks up at Norma, as if offering support; she gently cuffs him away. “Don’t look at me, Charlie.”

“He knows I’m upset,” she explains.

Norma’s body is laced with scars, some are fresher than others. She started self-harming when she was at Lagarie. Now aged 55, she looks back at her turbulent life and says, quite simply, it was “ruined by Mr Barrie”.

According to several accounts heard by BBC Disclosure, Mr Barrie was a prolific child sex abuser who used his position as a minister within the British Sailors’ Society to operate - or at least facilitate - a paedophile ring, with others connected to the organisation.

Stuart Rivers, who is head of the Sailors' Society - as it is now known - says the police were contacted about the allegations shortly after he took up his role in 2013.

He said: “It’s a very dark time in the society’s history. I was deeply upset by it. I can’t change the past, but I can make sure that that we do things right now. I think no organisation would feel good about having this type of thing in their history.

“I was horrified when I heard these accounts. We do regret that any abuse happened and we have apologised unreservedly.”

Mr Rivers said the charity is in touch with 18 survivors, and has provided counselling services to some of them. He called on other Lagarie residents to get in touch with him personally, and pledged his support to them.