By Beth Rose, BBC Ouch: PyeongChang

Conditions are good. Nineteen-year-old Millie Knight is preparing for a race that will see her hit speeds of 115km/h (71mph).

Registered blind, she will rely on her guide, Brett Wild, to talk her down the mountain. They are a team.

Fist bump. Ritual. A whispered chant from Irish band, The Script: “You could be the greatest, you can be the best, you can be the King Kong banging on your chest.”

Into the gates. “Three, two, one.” Wild pushes off. “Go.” Knight follows.

The mountain falls away.

The cut of skis on snow and the intense exchange of instructions is all that can be heard as Wild shouts out the course. Spectators stand silent, forbidden to make noise.

Knight only has 5% vision. It is peripheral and blurry but she catches glints of Wild’s orange jacket, which keeps her on track.

Twists and turns. Rhythmic. And then the final stretch, downhill, skis straight, body tucked. All out until they're over the line.

The mountain's silence is broken by cheering.

Knight and Wild have become champions in the World Para Alpine Skiing Championships. It's a first for Britain at such an event.

But Knight fails to stop. She crashes at 115km/h.

“I heard her on the comms screaming,” says Wild. “I looked back and could tell instantly how bad it was. She was getting rag-dolled and there was blood all over the snow. She slid on the ice and it ripped her face.”

Knight had skidded under an inflatable barrier, which re-inflated on top of her.

“She was saying she couldn't breathe,” says Wild.

Sports psychologist Kelley Fay watched the crash unfold.

“Brett was frantic. Millie wouldn't have known what was happening,” she says.

Knight was taken to hospital. Besides cuts and bruises, she was apparently unharmed and discharged in time for the medal ceremony.

Knight's injuries

The next day the pair returned to compete in the Super G - a form of slalom.

But as psychologist Fay took up her position at the bottom of the course, she felt uneasy.

“I knew Millie’s head wasn't in the right place,” she says. “So I radioed up and we pulled her out of the race. She was really cross, but in the end she could see we'd made the right decision for her.”

It was the first sign that all was not well with the teenager.

“We'd been skiing together for over a year and she'd never crashed,” says Wild. “Millie was known for staying on her feet.”

That was January 2017. A month later, in South Korea at a test event for the Paralympics, the blind skier found herself in hospital again.

“It was at the finish line again,” Knight says. “I flipped and landed on my head a couple of times and we were blue-lighted off to hospital.”

A diagnosis of concussion would take her off the ski slopes.

Recuperation included light gym sessions, but too much exertion could wipe her out for days.

That's when fear crept in.”

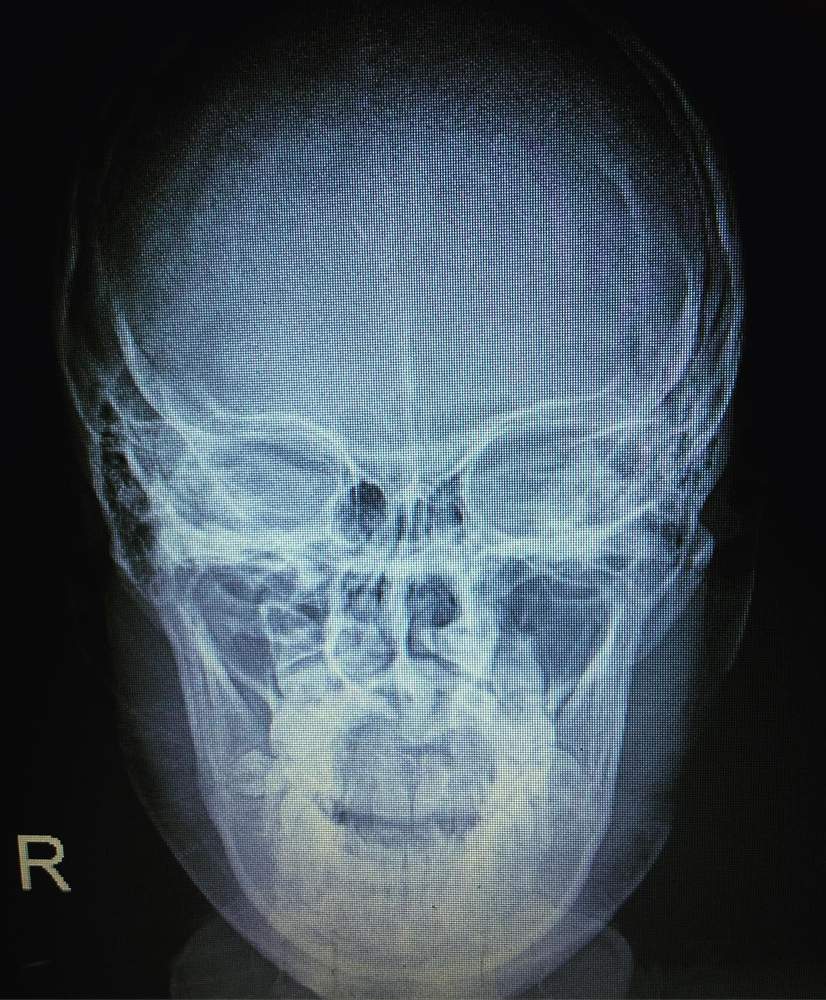

Knight's brain scan

Unable to confront the mountains, the fear started to eat away at her.

She threw herself into her school work - A-levels were looming - and her love of photography.

Knight photographs people and movement - skiing rarely features - and often sells her work.

“I take photos to see the world because the way I see it is very different,” she says. “It's almost like a new language to me. When I look through the camera I realise that's what everyone else sees.”

Knight started to prepare for her first solo photography exhibition. But as hard as she focused, her mind kept replaying the crash.

“I thought, ‘Have I lost this? Have I lost my bottle? Am I not going to be as good as I was?’”

Knight had always been known for her fearlessness. She has skied since she was six - the same age that she was left with 5% vision. As a baby, an infection scarred the retina of her right eye. Five years later the sight was gone in her left eye, too.

“I don't remember having sight,” she says. “It's not an event in my life and my mum never made a big deal about it.”

“She was a massive skier, so she just put me into ski school and didn't tell them I couldn't see.”

Knight stayed close to the instructor and became a natural follower on the snow.

Millie Knight

The family took annual ski holidays. It was something to create memories with and a chance to feel speed - after all, Knight would never ride a bike or drive a car.

“I can see about two to three metres in front of me but it's unclear and foggy,” she says. “Within that, I don't really have depth perception, so I don't know how far away things are.”

Millie Knight and her mother Suzanne

In 2012, when she was 12, Knight attended the opening ceremony of the London Paralympics.

“That was the moment I was like, ‘Wow I want to be one of those athletes.’”

Back at home in Canterbury, she contacted Disability Snowsport UK and began to focus on ski training. Her mother Suzanne acted as her guide.

At 13, Knight made it on to the UK development team and just two years later qualified for the Sochi Paralympics.

She became ParalympicsGB's youngest Winter Games athlete and was nominated as flag-bearer to lead the team into the Fisht Olympic Stadium.

Knight carries the flag

“I was thinking, ‘Why am I here, it's crazy’. I was so starstruck,” she says.

She was too young to compete in all the ski events but came fifth in the slalom and the giant slalom.

After the Games, Knight’s guide retired from the sport to go to university. Good guides are hard to come by, partly because of the expense. Unless they are at the top of their game, guides pay their own way. Others retire due to injury.

Over the following season, Knight went through eight guides. None was quite right.

Then in 2016, Knight’s development coach Euan Bennett, heard about a young Royal Navy skier who had represented Scotland at a junior level and thought he’d be worth a trial.

Brett Wild had joined the Royal Navy when he was 19. He grew up in Scotland where his dad managed Glasgow Ski Centre and his mum was an instructor.

They put Wild on the snow aged three and he competed for Scotland as a teenager. He travelled the world to training camps and competitions and almost went full time in his final year of school.

Brett Wild

Bennett told Wild that as a guide, he would need to ski a couple of metres ahead of Knight, but they wouldn't be tethered. They would communicate via Bluetooth headsets.

He would need to be proficient in five disciplines - Downhill, Super-G, Giant Slalom, Slalom and Super Combined, which is made up of one downhill run and a slalom event.

Wild was up for it and flew to Austria for a trial.

Knight was less sure. She had been used to older guides who took control and made decisions. Wild was just 23 and had no idea what he was doing. But he took to it quickly and easily.

Knight and Wild

As they descend a slope, Wild is expected to describe the terrain from the start gate to the finish line. A “steep here”, a “flatter” there, as well as the snow conditions - “bumpy”, “icy”, “soft”. He will also instruct Knight to turn at every gate for the rhythmical changes. If she can’t catch sight of his orange jacket in front of her, she will let him know by saying “off”.

“I was told her life is in my hands and that she’s my responsibility until she has her skis off,” says Wild.

After a week’s training, Knight threw Wild into the deep end by asking him to guide for her at an international competition in Aspen, Colorado, US.

The Navy agreed Wild could go but only if he returned immediately for a nine-month tour of duty.

Waiting for him in Aspen was Knight’s sports psychologist Kelley Fay. She wanted to ensure that her young charge would be in good hands.

“I could see his potential but he was just a boy. So I pulled him aside and had a stern conversation with him about what he needed to do,” she says. “He said I frightened the life out of him, but I wanted him to hit the ground running.”

The pep talk worked. By the end of the competition, the pair had picked up seven medals including three golds.

“It was hard to get my head around,” Wild says. “The week before I was pleased to win a bronze medal at the Inter-Service Championships. Then I had three gold World Cup medals to bring home.”

PyeongChang beckoned and the Navy agreed to release Wild for two years, on a reduced salary, to take Knight to the Winter Games.

But the crash a year later in South Korea changed everything for Knight. With just over 12 months to go, the blind skier was gripped with the fear of racing down a mountainside.

Her Paralympic hopes hung in the balance.

“Before my crash, I was confident because I had nothing to fear. But afterwards I was thinking, ‘Why am I doing this if it is going to cause me injuries?’”

“My performance is 80% psychological and 20% talent because when you’re standing there and you have that second of doubt - that's when things start to go wrong.”

Psychologist Fay says Knight was the most confident ski racer she had worked with.

“She wasn’t cocky but had a lot of self belief in what she could achieve. She had no anxiety before the crashes.

“After the first one we got her on her skis very quickly but the second one meant she was removed from that ski world. That made this particularly difficult to overcome,” she says.

Kelly Fay with Knight and Wild

Fay spent up to 90 minutes a day with Knight. Sometimes they would talk during a 10-minute ski-lift ride to redirect Knight's thoughts before the next run, or discuss her body language to make her look and feel more confident.

“You could see she was willing to do whatever it took, but whenever she put her speed skis on it just freaked her out,” Fay says. “Even when we were doing a gentle slope, she’d be saying ‘I can't do this’. She was that frightened.

“That was when we knew it was very serious.”

As time ticked away, they needed a breakthrough.

Kelly speaks to Knight and Wild

Fay accompanied Knight to Chile to the ParaGB training camp, in the hope she could establish where Knight's fear came from and why both crashes happened in the finish area. They started with the basics - how to stop.

“The guys are 100% committed all the way down for speed. But the last few gates are normally straight, so a lot of them switch off because it's just ‘go go go’,” says Fay. “We worked a lot to make sure she was staying fully engaged until they were stopped, but even that didn’t take the fear away.”

Then Fay had another idea - they would return to the site of the crash and face Knight's fears head-on.

The trio went back to the exact spot where the crash happened, where Knight's confidence had been shattered.

“It was about reprogramming my brain into thinking differently about it,” Knight says. “Changing my emotions towards it.”

Fay says: “It was getting her to accept that this is speed racing, so there's an element of risk involved. But if we did A, B and C that would minimise it.”

Knight and Wild

Wild, naturally, blamed himself for the crash and Knight’s subsequent loss of confidence. As her guide he was meant to be her eyes.

“I think of Millie as a little sister and I feel very protective of her,” he says. “I felt useless that I couldn’t help. All I could do was stay positive when she was losing belief in herself. There were times when she was upset and I didn't know what to do.

“I tried to stay positive, but it was out of my control. The problems were in Millie’s head.”

Knight's crash and loss of confidence had set them and their training back and they needed to make up ground on the snow.

Knight weight training

The got stuck into training. They needed to work on their trust and relationship both on and off the slopes.

Daily training would begin at 05:00. They practised relentlessly, eradicating any potential for error

“When I'm skiing all I can hear is Brett and his skis,” says Knight. “I'm only aware of following Brett's commands, I totally zone in and that's all I’m focused on.”

In January 2018 news came through that the pair had made the GB team for PyeongChang.

But the physical and mental hurdle of returning to the slopes in competition remained.

Had Knight's fears finally be conquered? The pair were to find out at a pre-Games competition in Canada.

They were faultless. Three bronze medals out of four. But the top accolade went to Knight and Wild’s team-mates - Menna Fitzpatrick and guide Jennifer Kehoe - who won two golds and a silver.

Their fight back to the top was not yet over.

Menna Fitzpatrick and guide Jennifer Kehoe

“Canada was good,” says Wild. “I don't think it's exactly where we wanted to be, but we're now back in the mix. We were about a second off the fastest girl so we are close enough. It’s just whether we can bring it all together on race day.”

But Knight saw it as proof her fears had dissipated.

“I think now I'm much stronger mentally. When I think about my crash I smile, I don't think of it and get worried any more.”

Knight and Wild

A gold medal hangs in the balance. But so does the partnership the pair has effortlessly formed.

The two years that Wild was granted by the Navy is almost up. He’s still part of the armed forces ski team but isn’t sure whether he will be allowed to continue working with Knight on another Paralympic cycle.

A gold medal might just swing it - and keep the pair together.

“I wouldn't want to follow anyone else down a mountain,” Knight says. “It would be devastating if we couldn’t ski together again.”