Robert Paxton McCulloch was already a multi-millionaire by the time he turned 18.

But inheriting part of his grandfather’s fortune in 1925 didn’t blunt his ambition or work ethic. Driven by a compulsion to invent, after graduating from Stanford University he started a company that created supercharged car engines.

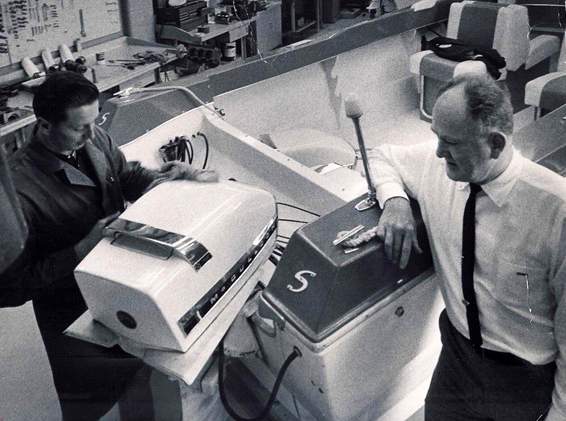

While he was still a young man McCulloch sold the business for $1m. It was the first chapter in a lucrative career that would take him from the Midwest to California, where he had successful ventures making chainsaws and boat engines.

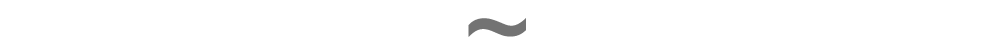

“He was a genius,” says his grandson Michael. “He was astute at building and invention; he designed engines - that was his forte.

“He was a little on the eccentric side, but extremely nice. I only ever saw a very gentle person.”

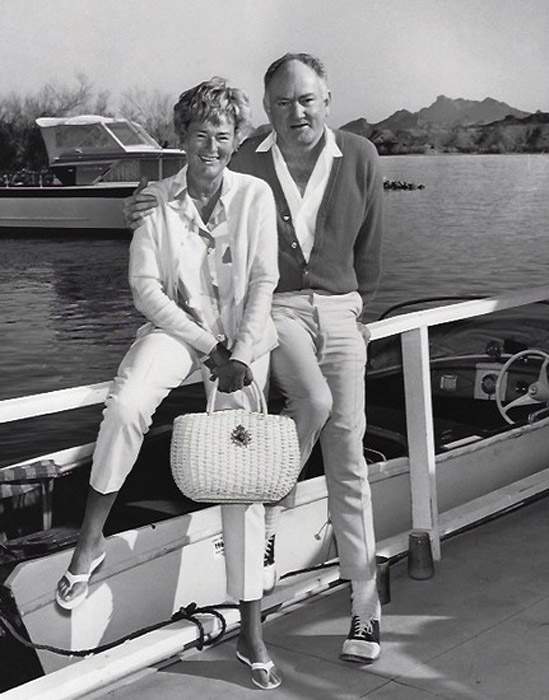

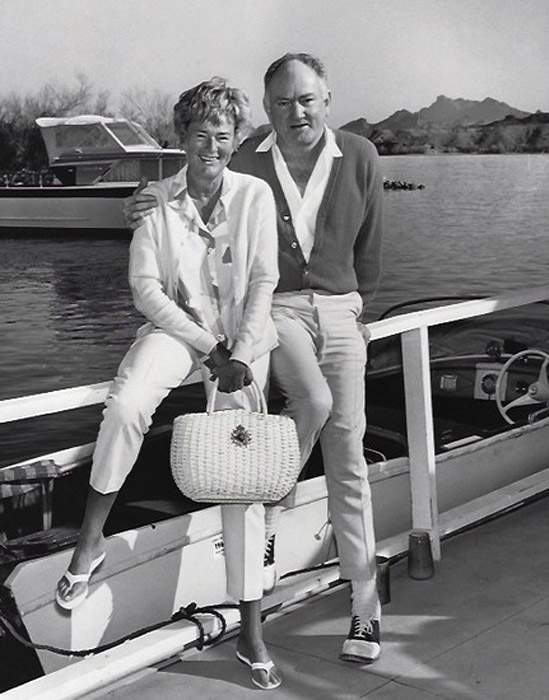

McCulloch married Barbara Ann Briggs, daughter of the co-founder of the engine company Briggs and Stratton

McCulloch, who was known to his grandchildren as RP, never lost his temper and was fun to be around, Michael says. He was something of a character who kept odd hours, working late into the night and sleeping until noon. Later, he would order the same thing at the same branch of Marie Callender’s pie place; a distinctive sight in the outfit he wore almost every day.

“It was a cream chino suit, a very thin black tie, a white shirt, and he had his trousers taken up three inches shorter. He would wear yellow socks, with white and brown saddle shoes,” says Michael.

“When he passed away, I wanted a pair of those shoes because that was his trademark. I opened the closet and there were 40 pairs of shoes and 25 suits and nothing else.”

Robert Paxton McCulloch was already a multi-millionaire by the time he turned 18.

But inheriting part of his grandfather's fortune in 1925 didn’t blunt his ambition or work ethic. Driven by a compulsion to invent, after graduating from Stanford University he started a company that created supercharged car engines.

While he was still a young man McCulloch sold the business for $1m. It was the first chapter in a lucrative career that would take him from the Midwest to California, where he had successful ventures making chainsaws and boat engines.

McCulloch married Barbara Ann Briggs, daughter of the co-founder of the engine company Briggs and Stratton

“He was a genius,” says his grandson Michael. “He was astute at building and invention; he designed engines - that was his forte.

“He was a little on the eccentric side, but extremely nice. I only ever saw a very gentle person.”

McCulloch, who was known to his grandchildren as RP, never lost his temper and was fun to be around, Michael says. He was something of a character and kept odd hours, working late into the night and sleeping until noon.

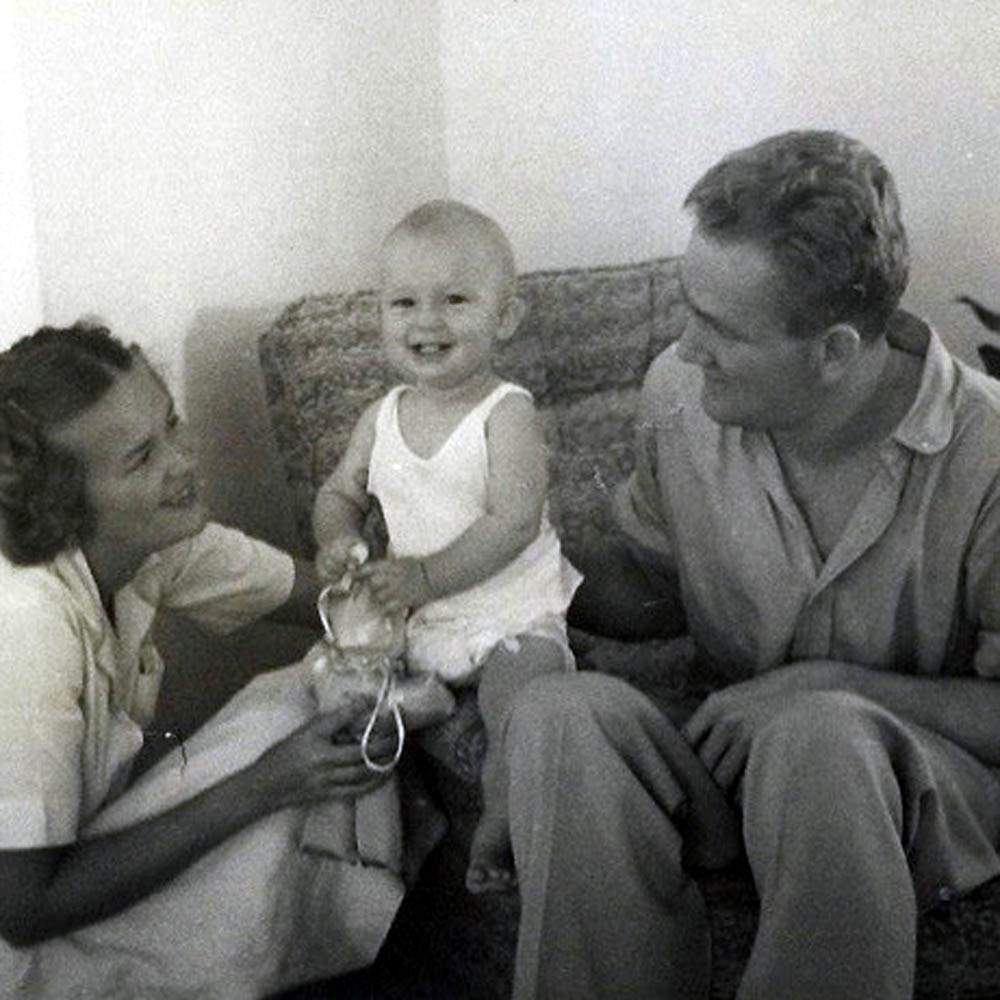

Robert Jr was the eldest of the couple's four children

Later, he would order the same thing at the same branch of Marie Callender’s pie place; a distinctive sight in the outfit he wore almost every day.

“It was a cream chino suit, a very thin black tie, a white shirt, and he had his trousers taken up three inches shorter. He would wear yellow socks, with white and brown saddle shoes,” says Michael.

“When he passed away, I wanted a pair of those shoes because that was his trademark. I opened the closet and there were 40 pairs of shoes and 25 suits and nothing else.”

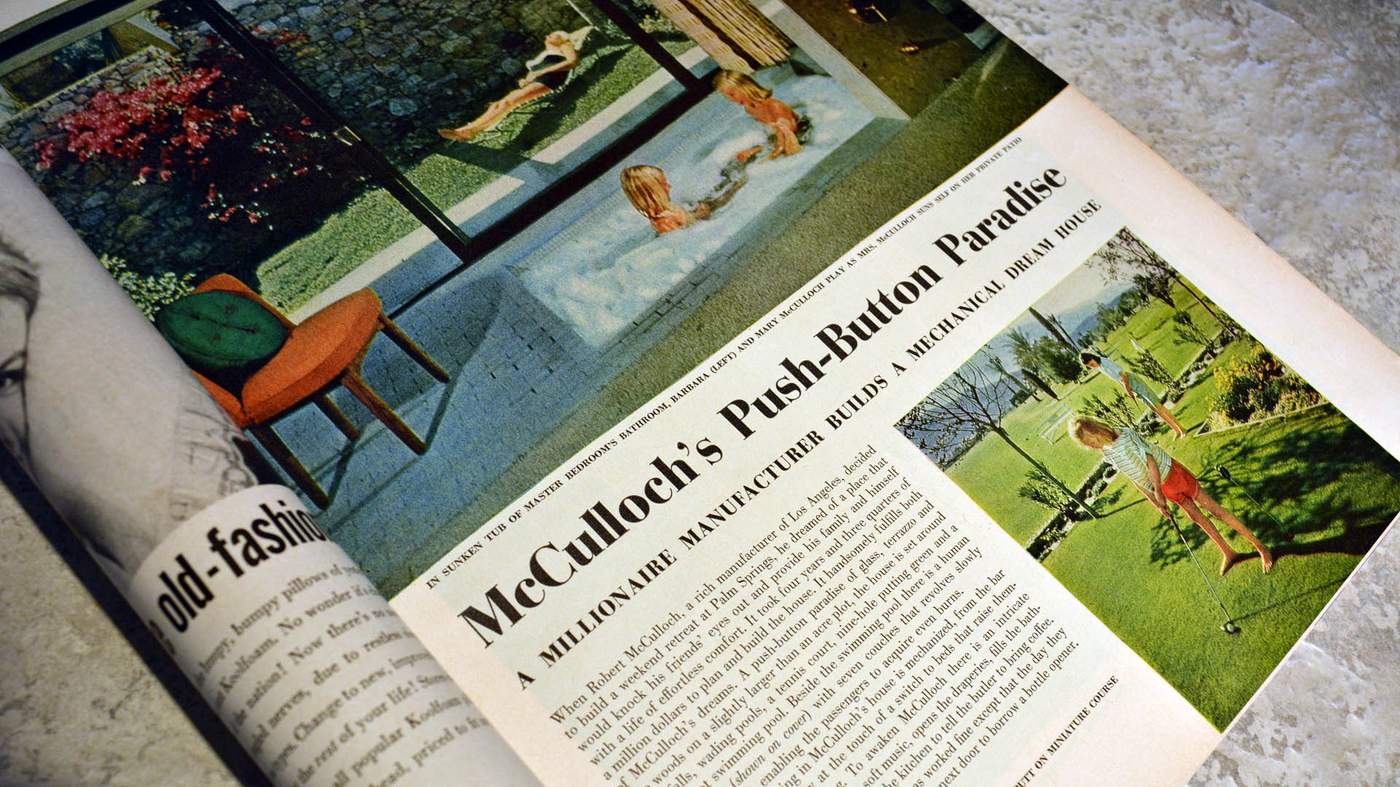

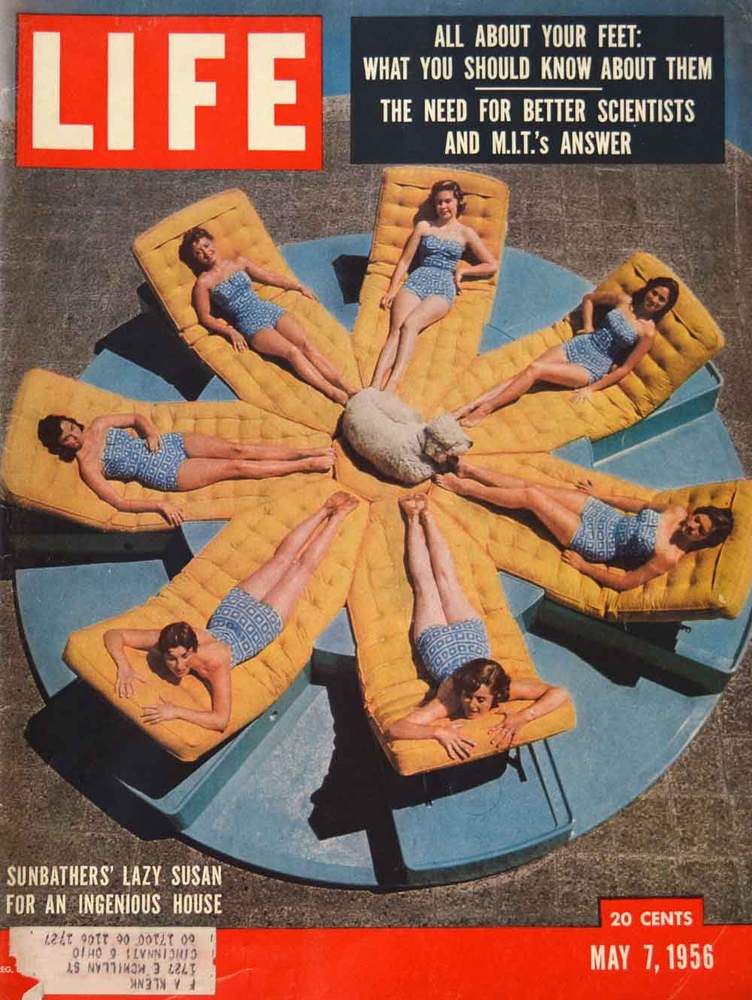

McCulloch was a man who fizzed with ideas and was often found tinkering at his holiday house in Palm Springs. It was a place of innovation, where the mundane became fascinating.

Drawers did not hold typical domestic trappings - they slid open to reveal chilled cocktail glasses. Such quirks led to Life magazine dubbing the country club home a “push-button paradise” in 1956.

The issue featured a number of McCulloch’s inventions

“It was way, way before its time,” says Michael.

“Everything was electronic. All the doors, all the drawers, everything opened by pushing buttons or by sliding a toggle.

“There were features that would turn on the coffee [machine] or the bath or the steam room at whatever time you wanted. All the lighting was controlled by a master panel. No other house had that.”

After a successful start in making racing engines, McCulloch branched out into boat engines

McCulloch was constantly looking for ways to make life easier. The magazine’s front cover featured another of his creations - a human “Lazy Susan” that rotated with the sun to ensure an even tan.

“He came up with a lot of ideas,” says Michael. “He created a jet pack, a two-person helicopter. He made a thing that was like a facelift [using] steam, which would tighten your skin.

“It was just something he did for fun. He was a very smart, creative person that needed to keep inventing.”

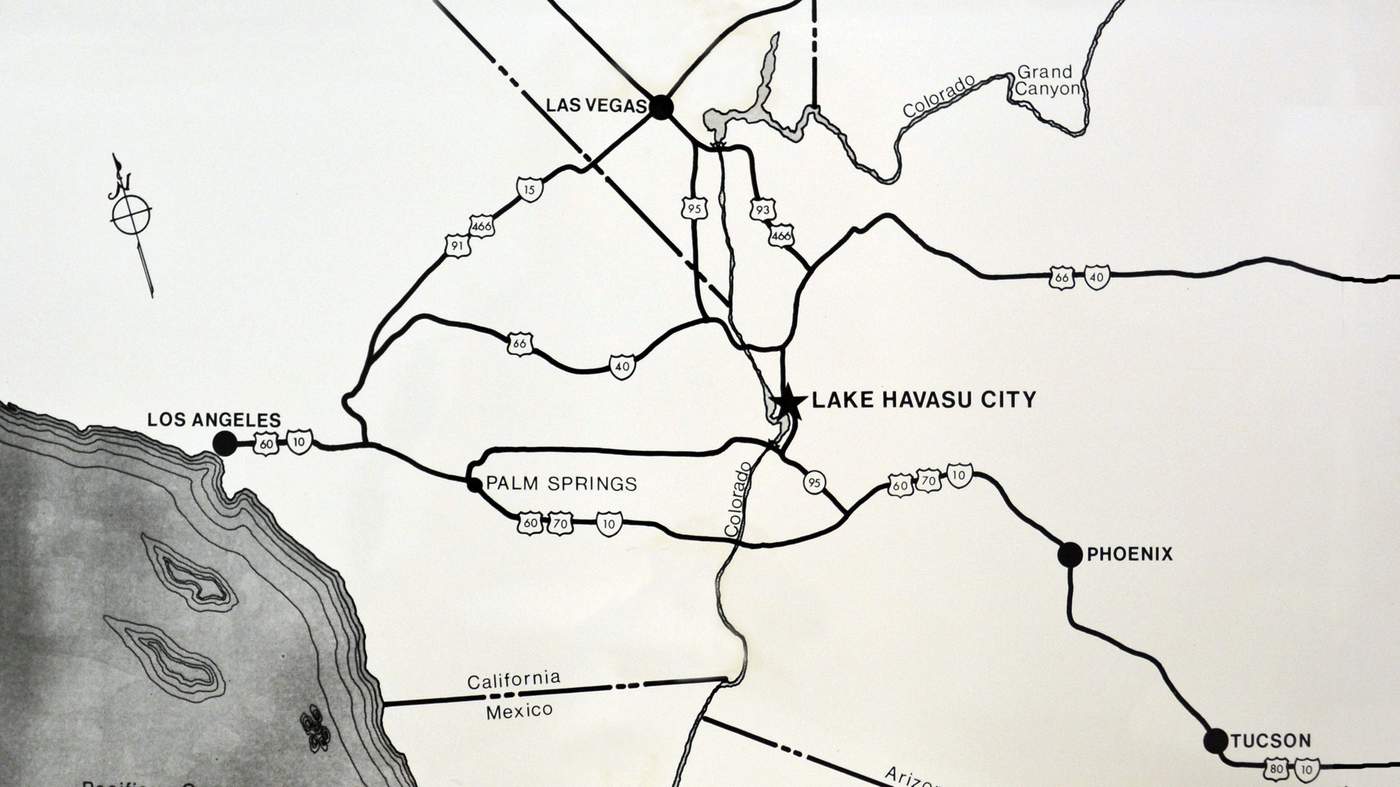

Lake Havasu was created after the completion of the Parker Dam in 1938, which held back the Colorado River

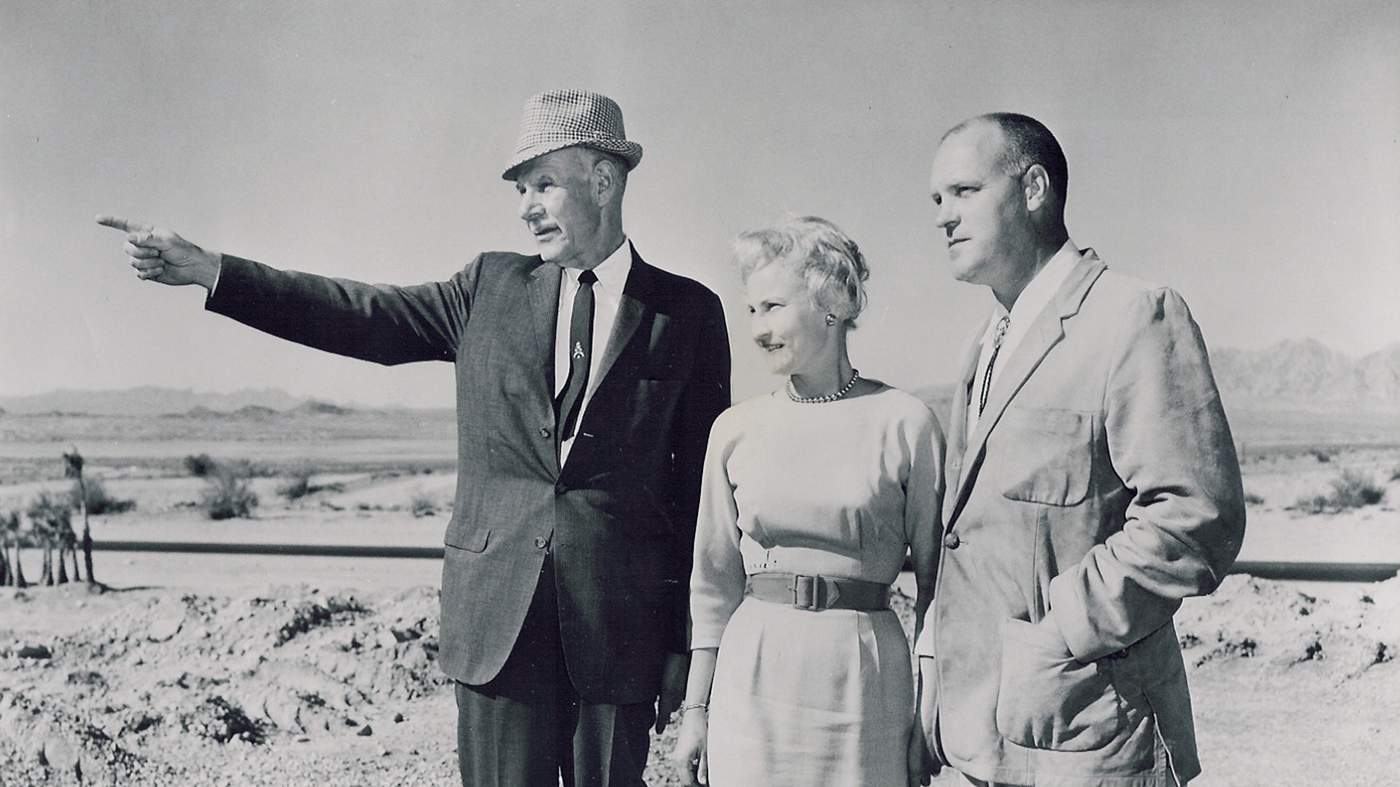

It was this compulsion, coupled with good business acumen, that led to his next project. With nowhere to test his boat engines in land-locked eastern California, he hopped over the border into Arizona in search of water.

The story goes that it was from the air that McCulloch spotted the ribbon of Havasu’s lake below, snaking through a parcel of land flanked by the Chemehuevi, Whipple and Mojave Mountains.

“They noticed it was a really, really beautiful place,” says Michael. “They took a look around, offered $76 an acre and started building.

“He realised there was a huge opportunity there.”

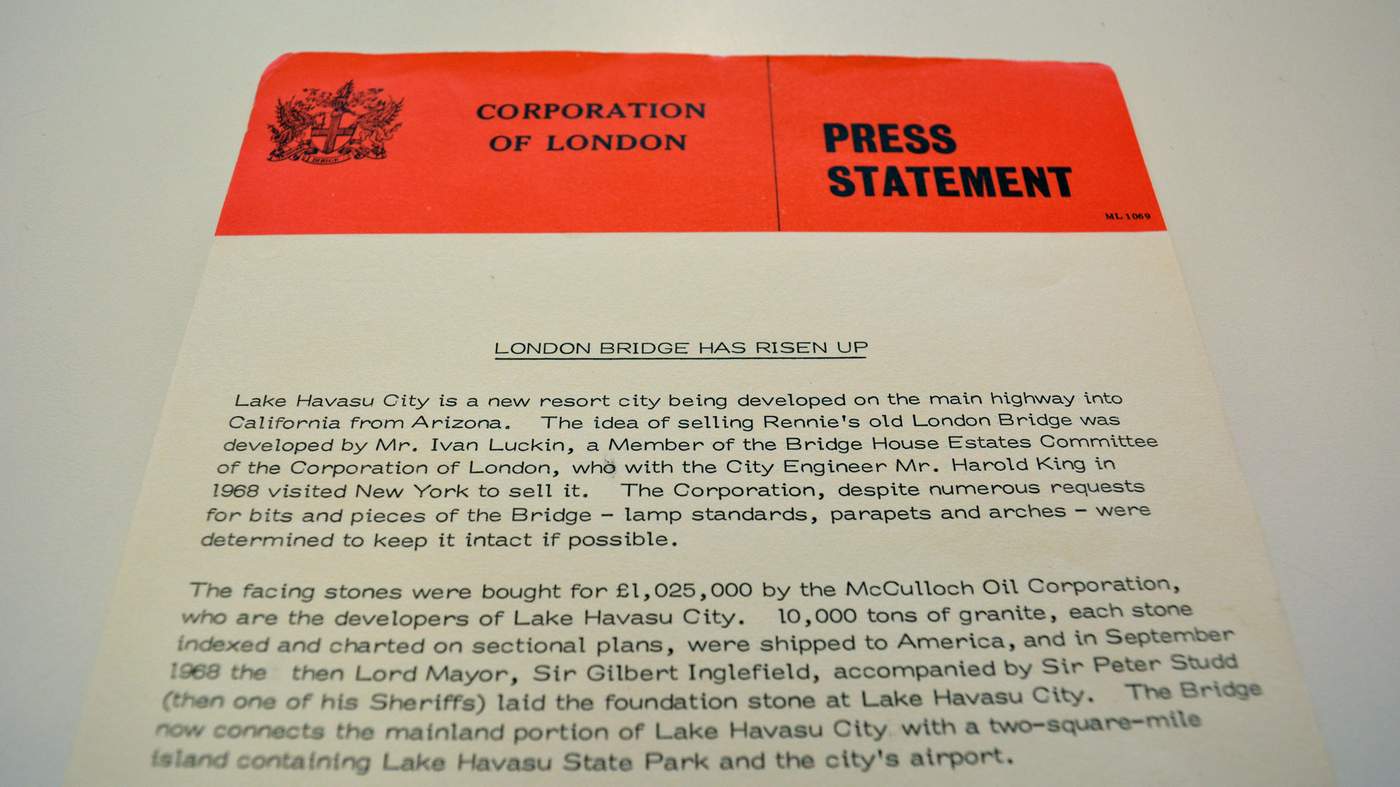

The Bridge House Estates committee of the City of London Common Council had known for some time London Bridge was sinking further into the River Thames with every passing rush hour.

Horse-drawn carriages had long since made way for cars and double-decker buses and, over the years, the structure had been hammered deeper into the riverbed.

The obvious solution to members in 1965 was to demolish it and start again; build a new bridge, for a new era of commuters.

Former newspaper and PR man Ivan Luckin had other ideas.

“He thought it was all very well knocking it down, but what about its future?” says former councillor Archie Galloway.

“That’s when Ivan made his move. He said to the committee, ‘we ought to sell it’.

“A lot of eyebrows went up at that.”

Luckin wanted to go a step further and advertise in the United States, where he felt certain someone would be interested in buying a well-known London landmark.

“Someone sensibly asked what they might get for [the bridge] and Ivan is recorded as saying, ‘one million’,” says Archie.

“And they said, ‘one million dollars?’

“Ivan said, ‘I’m talking about one million pounds.’ [Nearly three millions dollars at the time.] They sat up at that.”

News of the sale was soon the subject of newspaper and TV reports trotting out the inevitable line that London Bridge “was falling down”.

Luckin’s glossy 40-page brochure for prospective buyers promoted not only the structure itself, but the chance to own a slice of history - a bridge had crossed the Thames in this part of London since Roman times.

The new bridge was opened in 1973 by the Queen

It was this potential that inspired McCulloch and his business partner, Cornelius Vanderbilt “CV” Wood, who was known for designing Disneyland in California. Stories about how the pair got wind of the sale vary - according to Michael, they saw an advert on TV while on business in London.

“They had been having a few drinks together and saw it and I think they probably looked at each other and thought, ‘we should take that apart, that will be our gimmick’.”

Another version has Wood at a meeting about the sale of the RMS Queen Mary, at New York’s Plaza Hotel, where he supposedly asked, “anything else for sale?”

Either way, Luckin’s perseverance paid off and when the ink dried on the contract of sale on 18 April 1968, he was a man vindicated - his outlandish idea matched only by an even more ludicrous one.

“Ivan was immensely proud of it but never went around shouting it from the rooftops,” says Archie.

“I think a lot of people thought he was a lunatic, but he was a man of single purpose.

“I can’t believe anyone else would have thought of the idea.”

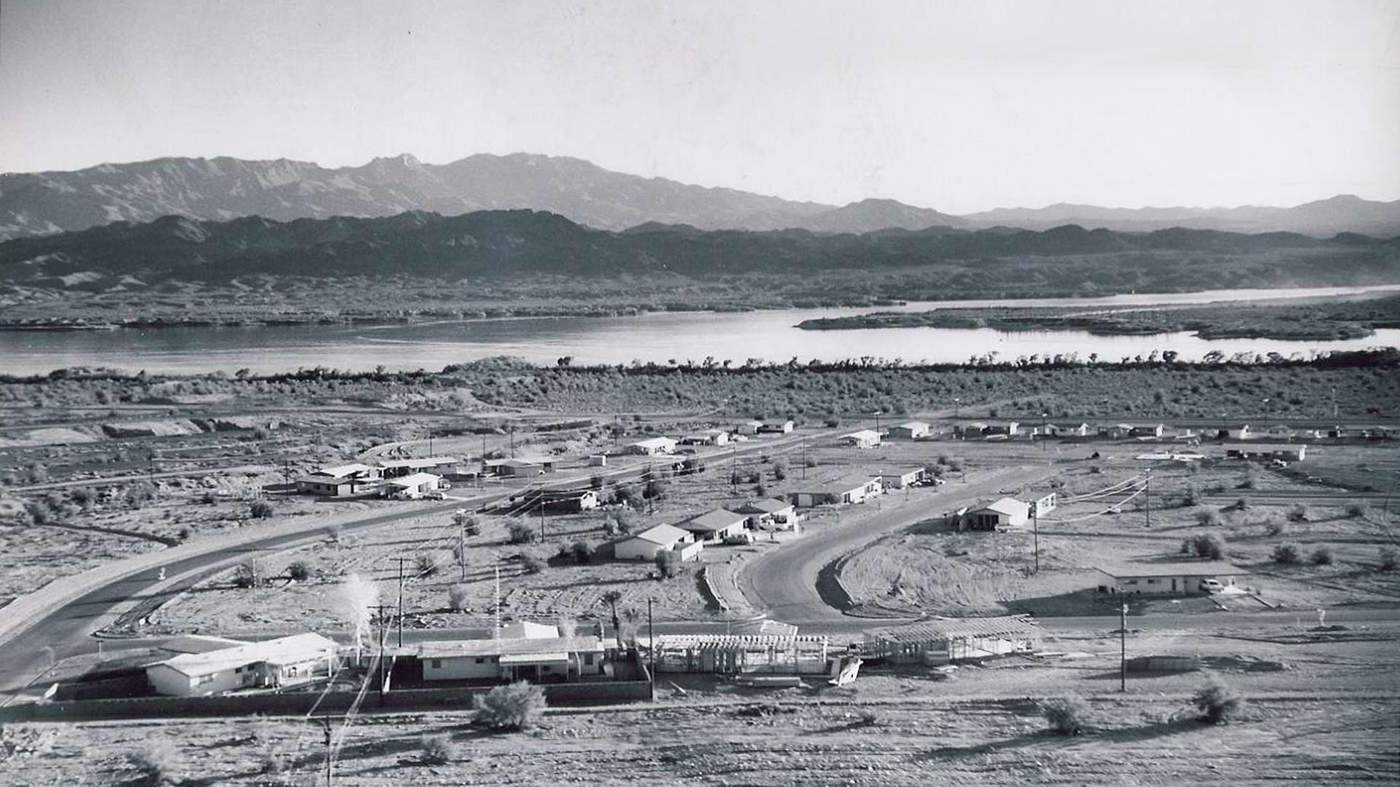

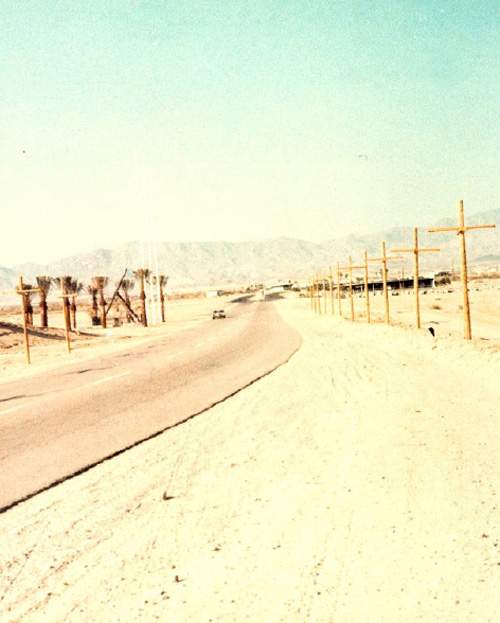

When his parents announced they were moving to Lake Havasu City in February 1965, Rick Kingsbury was incredulous. It sounded to him the place barely existed - and he was right.

“It wasn’t my idea to move here; no 13-year-old kid in his right mind would want to move to a godforsaken place like this at the time.

“We had no electricity, no water, we didn’t have air conditioning. There was one phone, the post office was a closet at the liquor store and the mail went to a box 20 miles away.

“Those first few months were like a big camping trip you were never going to go home from.

“There was nothing here. I hated the place.”

In 1965 there were about 20 homes and a trailer park

For Joe Hunnicutt, the worst thing was the dizzying heat of summers inching towards 50C (122F).

“I absolutely hated it. My parents took me out of Wyoming and they took me to hell.

“We came in August and I stepped outside and I was like,‘are you kidding me?’

“I was eight and all I wanted to do was ride my bike. I couldn’t do that there.

“My whole goal was to get out, but you’ve got to give it to them, the people that stuck it out in that godforsaken middle of nowhere.”

Those who moved to Lake Havasu between 1964 and 1974 call themselves pioneers - a nod to their 19th Century forefathers who travelled westwards in wagons in search of a better life.

But Rick wasn’t imbued with such spirit and it was a year before he saw the merits of living somewhere with one stop sign, two roads and 600 neighbours.

The first 10 houses were built in 1964 by Alfred Anderson

“I was a reluctant pioneer,” says Rick. “It was only during that second summer I realised what a paradise it was for a kid.

“There was all this exploring in the desert, so there was this feeling of Tom Sawyer, of living in this wonderland.

“We had this great big lake pretty much to ourselves and we were up to our necks in the cool water.

“It was this huge playground and it was all ours.”

By the end of 1965, the elementary school had acquired two new classes, and a grocery store had opened its doors.

The real change, however, came in 1968, when news trickled back to this tiny desert “city” that its founder had made a bizarre purchase.

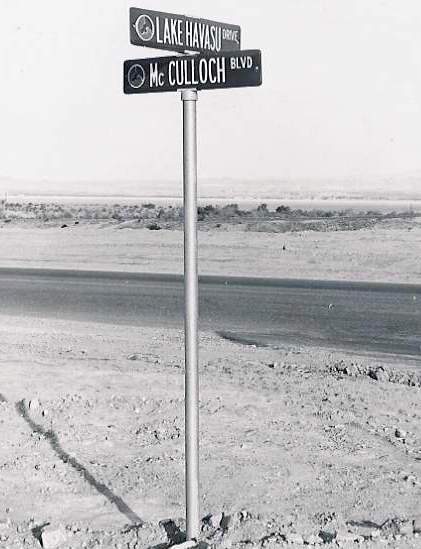

In the beginning there was just one major crossroad

“The whole economics of the place and the attitude of the town changed overnight,” says Rick.

“It was like a rocket ship, it took off and went crazy. In the three years it took to build the bridge, the population tripled.

“But there was almost a little regret for me. We were growing and I realised it was going to go away.

“It was all going to change.”

Visitors to Lake Havasu City might assume it existed only because its founder had embarked upon a curious plan to rebuild a piece of British history in the desert.

In reality, McCulloch’s small community grew steadily in its fledgling years. The US census recorded that by 1970 the city had more than 4,000 residents - a substantial increase on the handful that called it home six years earlier.

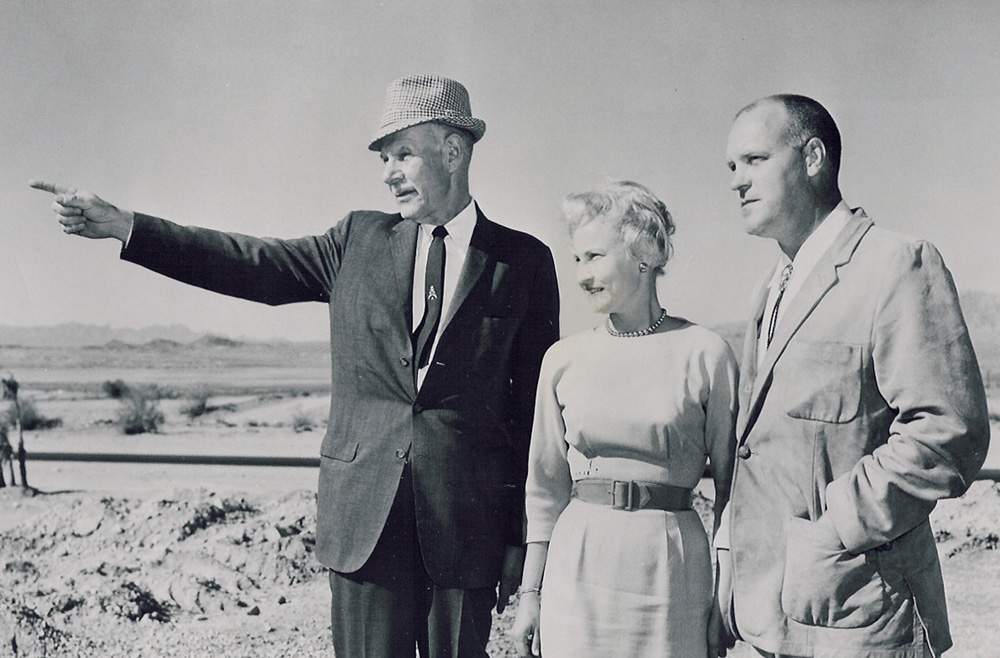

But even the engineer’s most faithful supporters struggled to share his vision back in 1964.

Early West remembers how in the spring of that year, he and McCulloch had been drinking coffee outside the entrepreneur's new factory in Lake Havasu when, seemingly out of the blue, he said: “I see a city.”

“I didn’t know what to say; there was nothing, just desert,” says Early.

“I said, ‘I don’t see that city’. And Robert said, ‘I promise, you will’.”

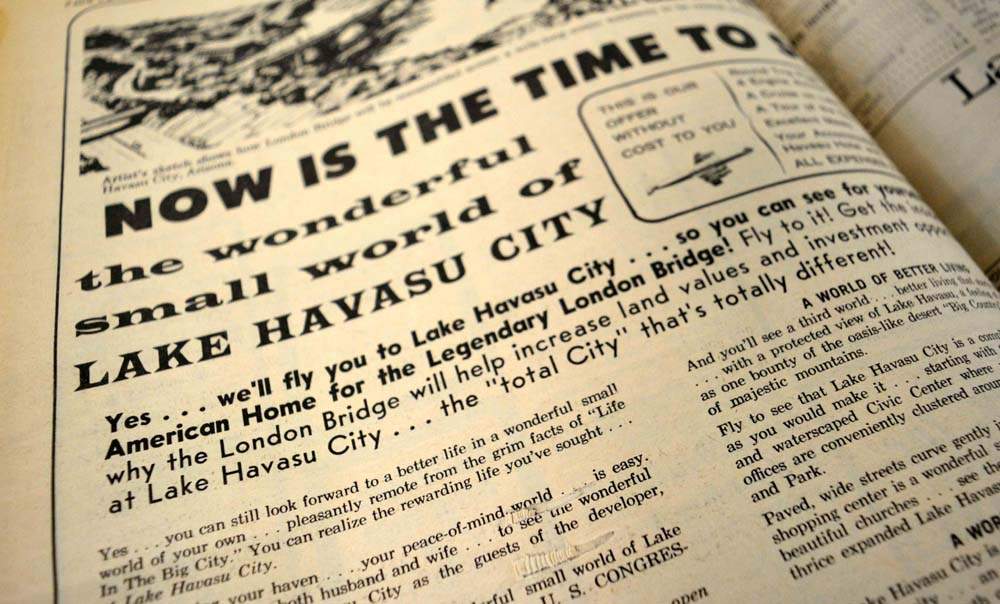

Adverts appeared in newspapers offering free trips to Lake Havasu City

Lake Havasu’s growth was in part down to dynamic marketing of the American dream - the promise of a better (and sunnier) life.

“RP started doing commercials and advertising in the Midwest where it was freezing,” says Michael.

“He purchased a bunch of planes and started flying people out on free flights.

“They were treated like kings. They were put up in a beautiful hotel for two or three days, had all their meals paid for and all they had to do was go on a tour for a couple of hours.

“And it worked like a charm. They sold a lot of those homes that way.”

Visitors to Lake Havasu City might assume it existed only because its founder had embarked upon a curious plan to rebuild a piece of British history in the desert.

In reality, McCulloch’s small community grew steadily in its fledgling years. The US census recorded that by 1970 the city had more than 4,000 residents - a substantial increase on the handful that called it home six years earlier.

But even the engineer’s most faithful supporters struggled to share his vision back in 1964.

The city’s first residents were given the grand tour by the salesmen

Early West remembers how in the spring of that year, he and McCulloch had been drinking coffee outside the entrepreneur's new factory in Lake Havasu when, seemingly out of the blue, he said: “I see a city.”

“I didn’t know what to say; there was nothing, just desert,” says Early.

“I said, ‘I don’t see that city’. And Robert said, ‘I promise, you will’.”

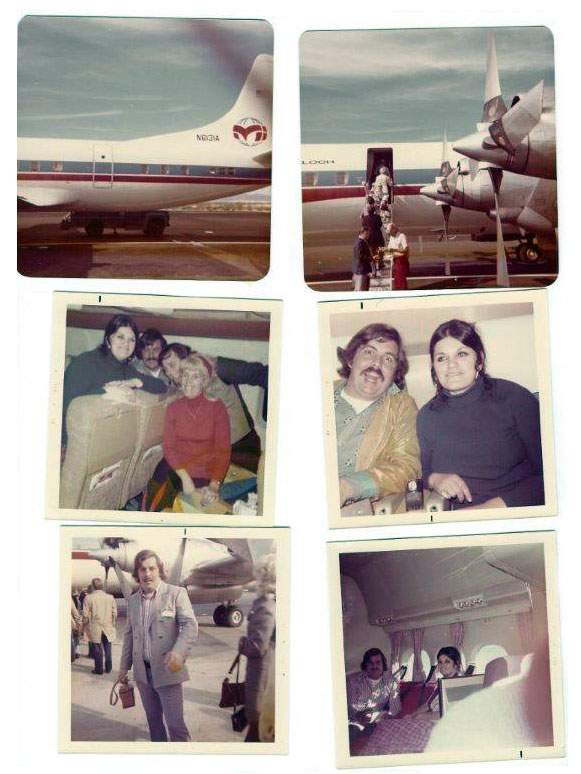

A salesman was assigned to each couple that stepped off the plane

Lake Havasu’s growth was in part down to dynamic marketing of the American dream - the promise of a better (and sunnier) life.

“RP started doing commercials and advertising in the Midwest where it was freezing,” says Michael.

“He purchased a bunch of planes and started flying people out on free flights.

“They were treated like kings. They were put up in a beautiful hotel for two or three days, had all their meals paid for and all they had to do was go on a tour for a couple of hours.

“And it worked like a charm. They sold a lot of those homes that way.”

Hundreds boarded the McCulloch-branded propeller planes on chilly runways in Chicago, Boston and New York. On arrival, they were chauffeured to the Havasu Hotel, where a waterfall cascaded dramatically over its front door.

“It was unbelievable,” says Evie Cistaro, who visited from Boston on the Thanksgiving weekend of 1972.

“We stopped and picked up people in Pennsylvania and Chicago and when we arrived it was 75F (24C) and the sun was shining.

“They wined us and dined us and showed us the land, and we bought it and signed.

“It was a new beginning.”

A salesman was assigned to each couple that stepped off the plane

Joe Hunnicutt remembers hearing the sales pitch from his father, Ray, who sold lots for McCulloch.

“They drove people around to buy property and I used to sit in the back of the Jeep with them,” he said.

“I had that [pitch] memorised... some of it was true, some of it wasn’t.”

Hundreds boarded the McCulloch-branded propeller planes on chilly runways in Chicago, Boston and New York. On arrival, they were chauffeured to the Havasu Hotel, where a waterfall cascaded dramatically over its front door.

“It was unbelievable,” says Evie Cistaro, who visited from Boston on the Thanksgiving weekend of 1972.

“We stopped and picked up people in Pennsylvania and Chicago and when we arrived it was 75F (24C) and the sun was shining.

“They wined us and dined us and showed us the land, and we bought it and signed.

“It was a new beginning.”

Evie Cistaro said there were about 100 people on their flight

Joe Hunnicutt remembers hearing the sales pitch from his father, Ray, who sold lots for McCulloch.

“They drove people around to buy property and I used to sit in the back of the Jeep with them,” he said.

“I had that [pitch] memorised... some of it was true, some of it wasn’t.”

Betty Gunnarsson says several salesmen were waiting at the airstrip in matching blue blazers after the 13-hour flight from Long Island.

“As soon as we got off the plane the pressure was on,” says the 75-year-old.

“The salesman took us out on a boat and to show how clear the water was, he dipped a glass in the lake and drank it.

“So we bought a bit of property. I thought, ‘it’s an investment’.

“But I remember people walking up and down the aisles [on the flight back] saying, ‘who wants to buy a pile of rocks?’

“And I thought, ‘they don't see beyond’.”

Evie’s salesman brother, Jay Scavusso, found the Gunnarssons their home

The Gunnarssons moved three years later into the only house on an undeveloped hill.

“People used to say… ‘you live way up there?’,” says Brooklyn-born Betty.

“You could look out for almost a mile. The boys had bikes and they would go out into the desert and [crumble crackers] to make trails so they didn’t get lost.

“The experience opened up their eyes. It was a good life.”

Before April 1968 few people knew where Lake Havasu City was, but news of the sale made international headlines and gave the tiny desert community a high profile.

However, the purchase of London Bridge was also the source of much scorn. Many people assumed McCulloch had lost his mind - although others recognised there might be some cunning behind the bizarre scheme.

“There were lots of articles that described RP as crazy,” says Michael. “Then that changed - to crazy like a fox.

“People couldn’t conceptualise it… take this bridge in London and put it in the middle of the desert?”

A rumour that McCulloch - a millionaire and successful businessman - had “bought the wrong bridge” probably didn’t help, although it was, of course, complete nonsense.

McCulloch and Wood went to London to inspect their purchase

“I know for a fact they knew exactly which bridge they were going to buy,” says Michael.

“Do you think anyone in their right mind would look at Tower Bridge and think they could take it apart and bring it here?

“But RP and CV felt that by allowing that rumour to perpetuate, it gave them continued publicity, so they let it go.”

Before April 1968 few people knew where Lake Havasu City was - but news of the sale made international headlines and gave the tiny desert community a high profile.

However, the purchase of London Bridge was also the source of much scorn. Many people assumed McCulloch had lost his mind - although others recognised there might be some cunning behind this bizarre scheme.

“There were lots of articles that described RP as crazy,” says Michael. “Then that changed - to crazy like a fox.

“People couldn’t conceptualise it... take this bridge in London and put it in the middle of the desert?”

A rumour that McCulloch - a millionaire and successful businessman - had “bought the wrong bridge” probably didn’t help, though it was, of course, complete nonsense.

McCulloch and Wood went to London to inspect their purchase

“I know for a fact they knew exactly which bridge they were going to buy,” says Michael.

“Do you think anyone in their right mind would look at Tower Bridge and think they could take it apart and bring it here?

“But RP and CV felt that by allowing that rumour to perpetuate, it gave them continued publicity, so they let it go.”

In the soon-to-be-home of London Bridge, the jokes were in abundance.

“We started a rumour McCulloch was going to bring the Leaning Tower of Pisa and put it in the park,” laughs Rick Kingsbury.

“We didn’t need a bridge,” says Bobbi Holmes. “We thought, ‘for where?’”

She had watched Lake Havasu City grow from her family’s tiny resort six miles away on the California side of the lake.

“We only had three TV channels and we didn’t have a local newspaper, but I remember hearing from someone that McCulloch was buying London Bridge and thinking it was just a silly rumour.

“We thought it was hilarious, we thought it was a joke.”

Bobbi Holmes remembers seeing the bricks piled up on the side of the road

The nearest high school was in the city, so Bobbi had to take a boat across the lake.

She remembers how the McCulloch salesmen would point her out as a local curiosity to those fresh off the flights, and say “there’s the girl that comes by boat”.

She watched as the bricks piled up on the side of the road slowly transformed into a bridge.

“I thought it was pretty bizarre at the time,” she says.

After all, there was no river in the city for the exported bridge to cross.

“Most people build bridges to cross a river, McCulloch built a river under a bridge.”

English expat Linda Binder felt similarly when she heard the bridge she had often walked across as a child was moving.

“I saw in the papers McCulloch was buying London Bridge and I thought, ‘what are those crazy Yanks doing building a bridge on sand?’

“But I think he did an extraordinary job of bringing it over and having the foresight to bring it brick by brick and rebuild it with the city around it.

“I mean, who does that?”

Years later, the Londoner moved to Lake Havasu where she became an Arizona state senator and, for many years, the point of contact for British dignitaries visiting the new city.

Her husband, Bill, recalls how his friend CV Wood had to get permission from the President of the United States to create a channel under London Bridge.

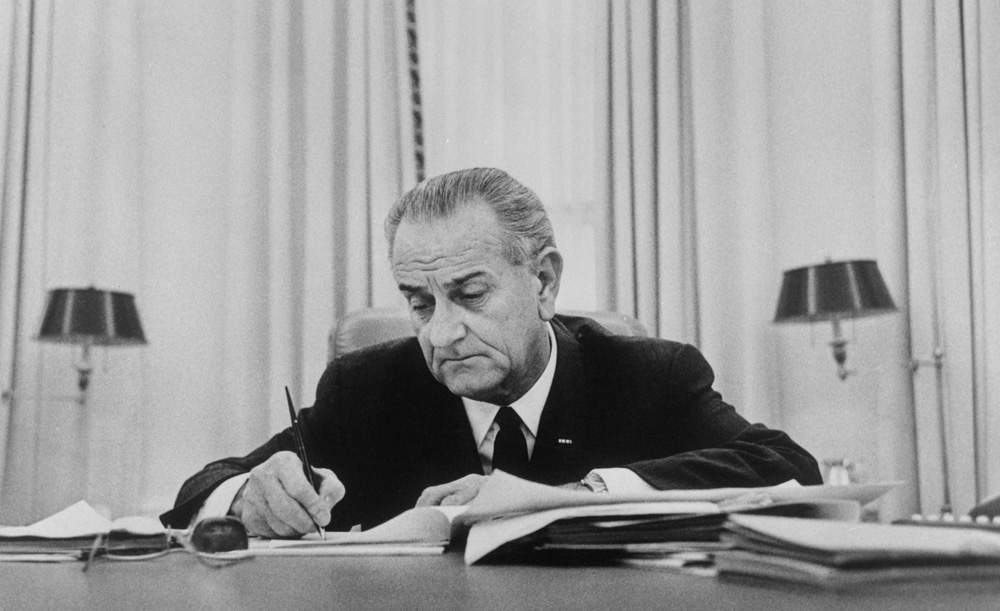

US president Lyndon B. Johnson had to be persuaded by Wood to sign off on the channel

“Woody told me the [plan] was to build the bridge on dry land and dredge it out, but they applied for a permit and got denied,” says Bill.

Wood was told such permission could be only be granted by the highest authority in the land, so he used his connections to secure a 10-minute audience with Lyndon Johnson, only to be told by the president: “Sorry, you can’t set this precedent. You can’t move a river.”

“Woody said the pressure was really on,” says Bill. “He was a Texas boy and so was Johnson, so he started talking with this Texan accent.

“He said ‘by golly, the next time someone buys London Bridge and moves it to the US, well, you’ll have to move another damn river’.

“Johnson looked at Woody and said, ‘sign it’ [to an aide about the necessary paperwork] and left the room.”

Wood, right, was an instrumental part in McCulloch’s plan

It wasn’t the only time Wood - who was married to Hollywood actress Joanne Dru - put his famed persuasiveness into action. He is also said to have taken less than two hours to convince 16 environmental agencies opposed to the bridge to get on board.

“The reality is RP was an engineer, an entrepreneur,” says Michael.

“But CV, he was a showman; he could sell ice to Eskimos.

“That’s why they were so good together. They made a good pair.”

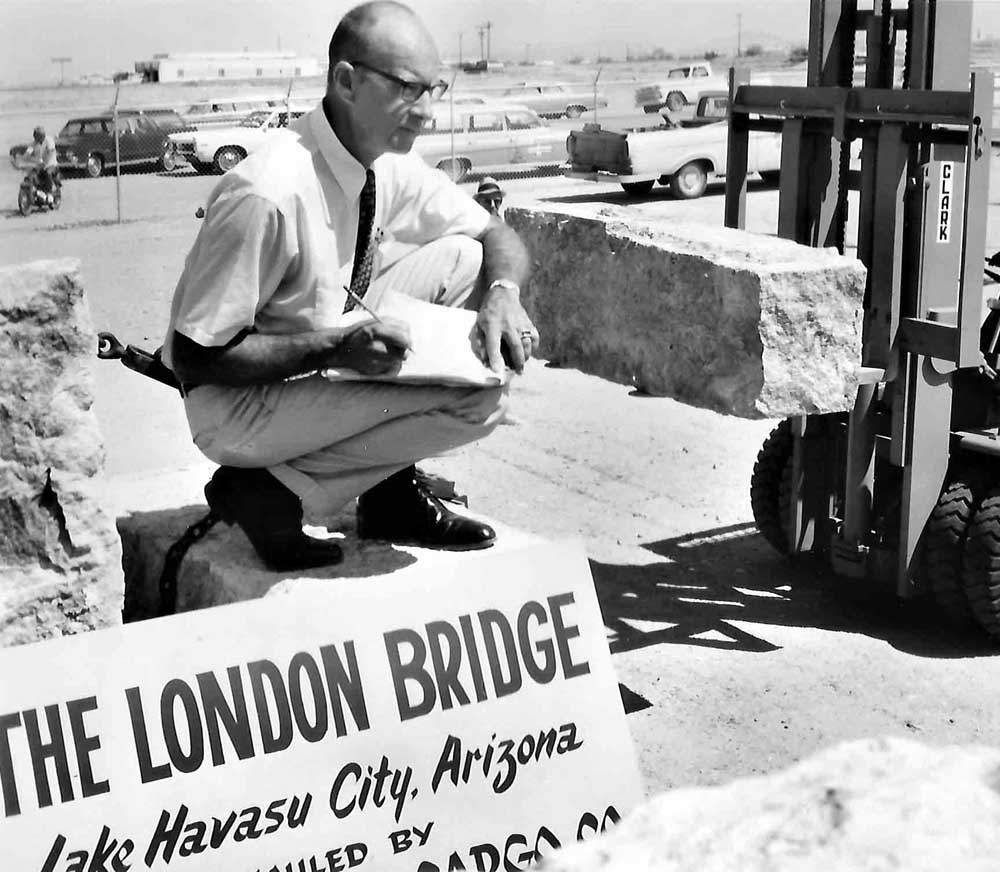

The first stone arrived in Lake Havasu on 9 July 1968, its swift delivery in part because work had begun to take it down long before McCulloch had signed a cheque for $2.46m.

Alan Saines numbered the pieces as they came off the bridge in London.

“There was only me numbering them and there were hundreds. If we did 20 a week, we were lucky.

“It wasn’t a case of smashing it; the [stones] had to be taken down carefully and stored carefully and all the time they were building the new bridge.”

Alan Saines was 17 when he got his first job, taking down the bridge

Alan Simpson worked on the design of the new bridge for engineers Mott, Hay and Anderson. He said the old bridge came down in slices to make room for the new one.

“The only way of doing it was to take down one side of the old bridge so there was just room for the new bridge, then move over to the other side, switch the traffic, then take down the rest of the bridge in the middle and tie [it] back together.

“It was complicated. And it wasn’t until fairly late in the day that taking it all down carefully to ship halfway around the world became an additional requirement.”

Dockers put the stones on to freighters bound for the US

The stones were sent to Surrey Docks, where fellow Mott engineer Bernard Waterworth would consult a long-range telescopic photo of the bridge and direct some pieces on to freighters bound for Long Beach, California, via the Panama Canal.

Others first went to Merrivale Quarry in Devon, where the faces were sliced off to cut down on shipping costs, before continuing their 5,000-plus mile journey.

“It was an historic monument and you were aware it was unusual,” explains Bernard.

“You don’t forget it - projects like that are few and far between.”

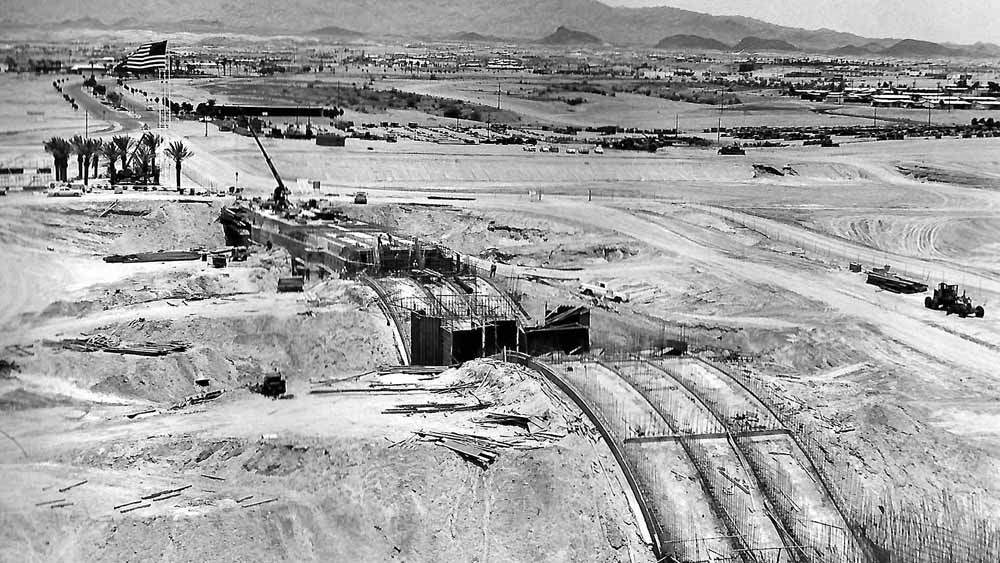

About 10,600 stones arrived in Lake Havasu, making the final leg of the journey by road on flatbed trucks.

Curious tourists would line the roads to watch them trundle into the storage compound, where the stones were unloaded and put in order, ready to be used by construction crews.

The interior of the bridge was sold for $2.5m and made into counter-tops and headstones

“We would see the trucks coming down the highway and we would sit and watch them go by,” says Norma Grzesiowski, who had just moved to nearby Desert Hills.

"We were thinking, ‘what are they doing? What are they building?’”

The cornerstone was lowered by Sir Gilbert Inglefield as McCulloch and Wood looked on

“We decided to steal some of the stones and the four of us were in my ’53 Chevy station wagon waiting with bolt-cutters to get in the yard,” remembers Rick Kingsbury.

“But those things weighed three times as much as my car did! The ground was shaking as they went by on those eight-axle trucks.

“We thought... ‘well that’s a bad idea’.”

About 10,600 stones arrived in Lake Havasu on flatbed trucks.

Curious tourists would line the roads to watch them trundle into the storage compound, where the stones were unloaded and put in order, ready to be used by construction crews.

The interior was sold for $2.5m and made into counter-tops and headstones

“We would see the trucks coming down the highway and we would sit and watch them go by,” says Norma Grzesiowski, who had just moved to nearby Desert Hills.

"We were thinking, ‘what are they doing? What are they building?’”

The cornerstone was lowered by Sir Gilbert Inglefield as McCulloch and Wood looked on

“We decided to steal some of the stones and the four of us were in my ’53 Chevy station wagon waiting with bolt-cutters to get in the yard,” remembers Rick Kingsbury.

“But those things weighed three times as much as my car did! The ground was shaking as they went by on those eight-axle trucks.

“We thought... ‘well that’s a bad idea’.”

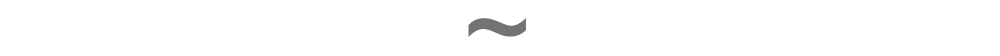

The cornerstone was laid on 23 September 1968 in a ceremony attended by London’s lord mayor.

Then work to resurrect the bridge began, starting with the arches, which were laid across the sand.

The rebuild began by calculating the angle of the arches

“You just saw the skeleton going up, and then they put the face on,” says Norma, who used to sit in a boat on the lake and watch.

“The builders explained it was like putting together a puzzle. It was exciting, but it was surreal.”

Construction workers had to build the bridge in the sweltering Arizona heat

The rest was built around the framework in reinforced concrete. To avoid the sinking fate of its 133,000-tonne predecessor, it was made hollow and finished with a veneer of stone, making it 33,000 tonnes.

“It almost felt like I was in a movie,” says former labourer Roy Martin, who helped winch the stones.

“People were always coming up to us and asking questions, wanting to take pictures and wanting to know if we had any extra pieces they could take home as souvenirs.”

The stones were manoeuvred in by hand and secured with pins, wire and concrete. The work was slow and laborious - crews had to force the 400-500lb pieces in one at a time. On a good day they’d get through 10; the worst was one.

If a stone was too damaged to use, it had to be replaced, says Harvey Robertson, who laid steps on the south side of the bridge. But the local rock didn’t match that which had been blackened by a century of London pollution.

“It was a lighter colour, so they had these kerosene burners making soot,” he recalls.

“Then they painted it on there to make it look dark and weathered, so people wouldn’t know they weren’t the original stones.”

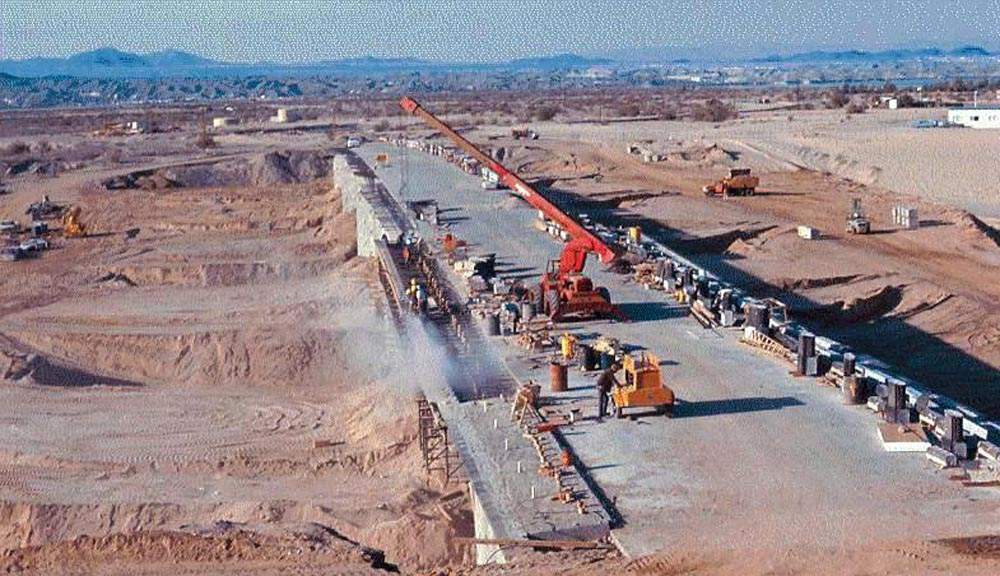

The dredge swung across the channel, eating out a path for the water

Once the bridge was up, the dunes were sucked out of the arches to make way for the president-approved channel.

The land underneath the structure was dredged, allowing London Bridge to tower above a waterway for the first time since it had left Britain.

“I remember thinking at the time McCulloch had more money than sense,” says Harvey.

“But once I started working on it, I thought he was pretty much a genius.”

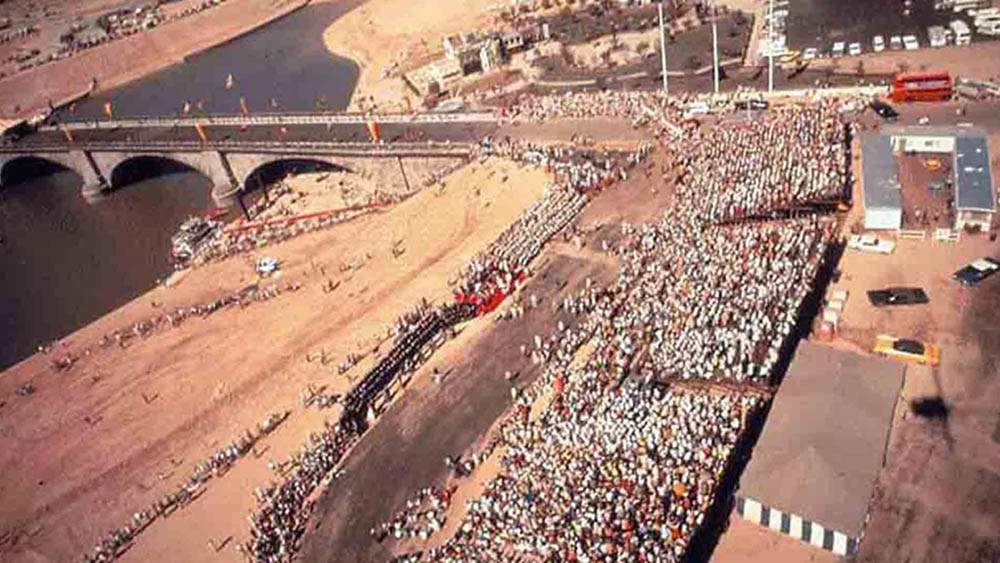

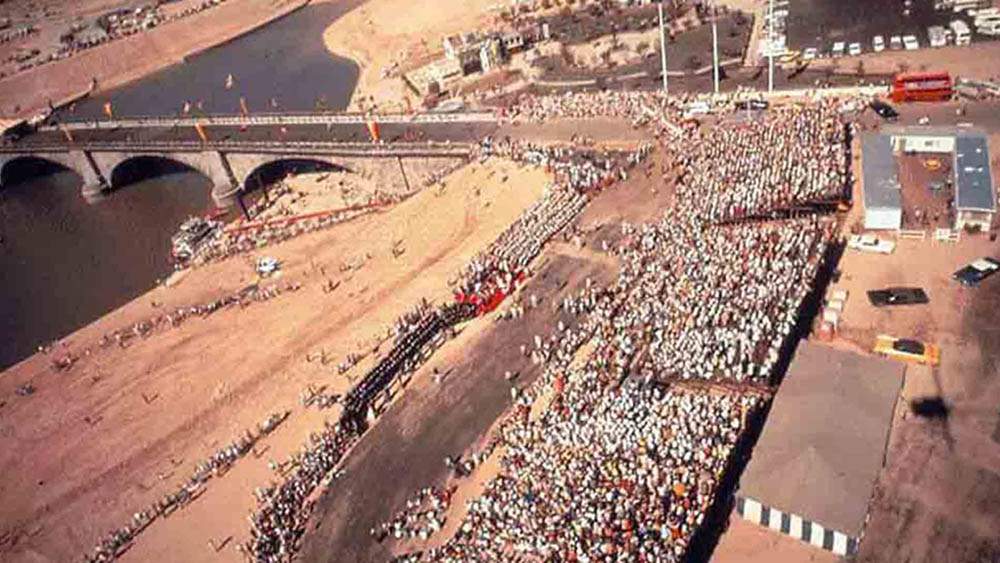

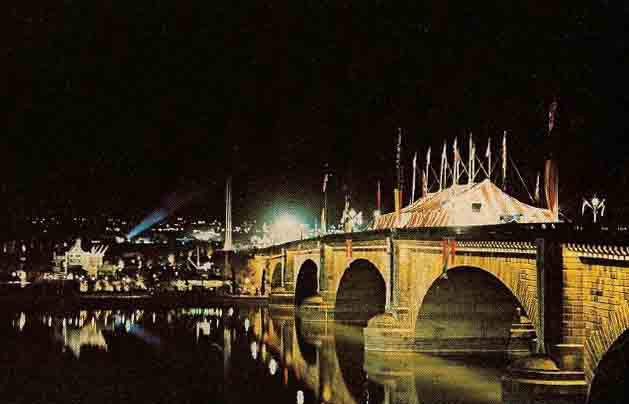

On 10 October 1971, Lake Havasu’s London Bridge opened to great fanfare.

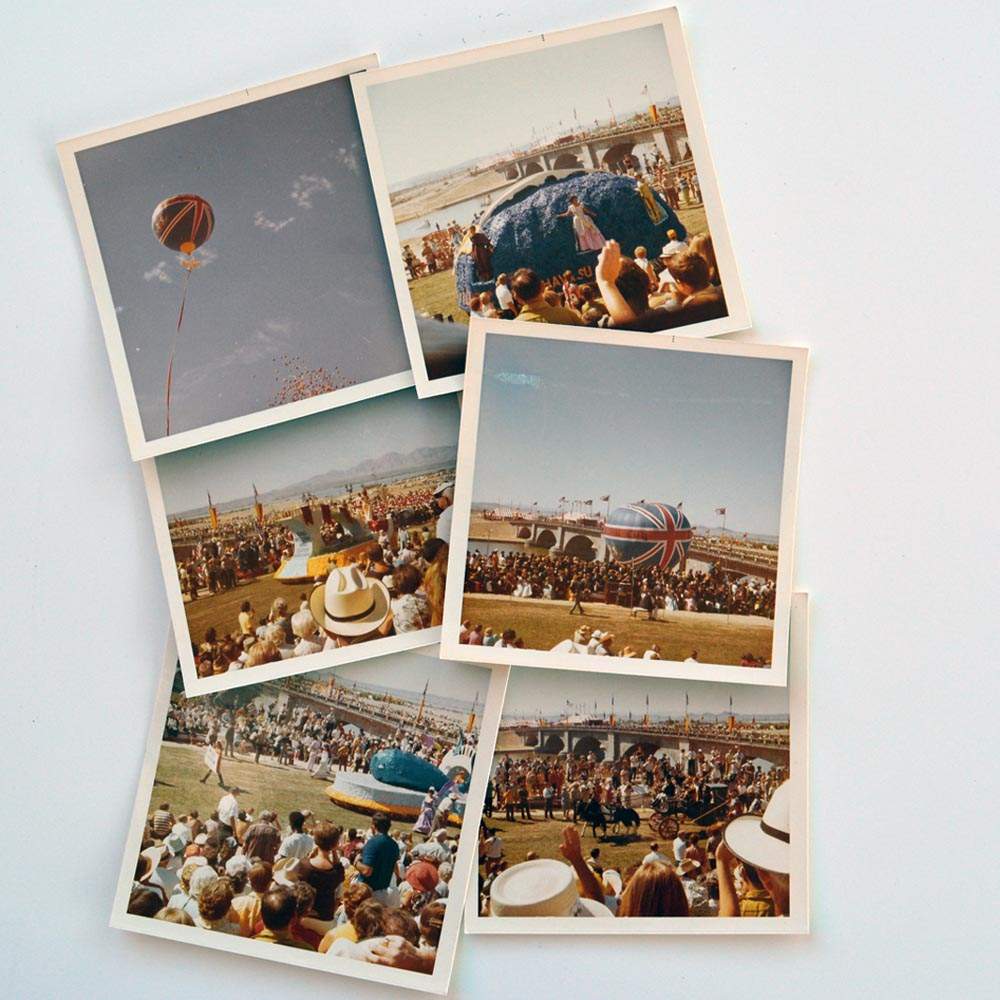

The British were out in force, represented by a delegation from London accompanied by a troupe of red-jacketed horse-riders trotting through the desert.

McCulloch, London's lord mayor Sir Peter Studd and Wood attended the dedication

The English Village offered a taste of home with its red phone box, double-decker bus and pub serving Yorkshire pudding and roast beef.

But the jewel was the bridge, with the British and US flags flying down both sides.

Riders on horseback made a strange sight against the desert backdrop

“The whole place was just buzzing,” says Norma Grzesiowski.

“They had a big tent down there on the bridge and lots of events and games going on.

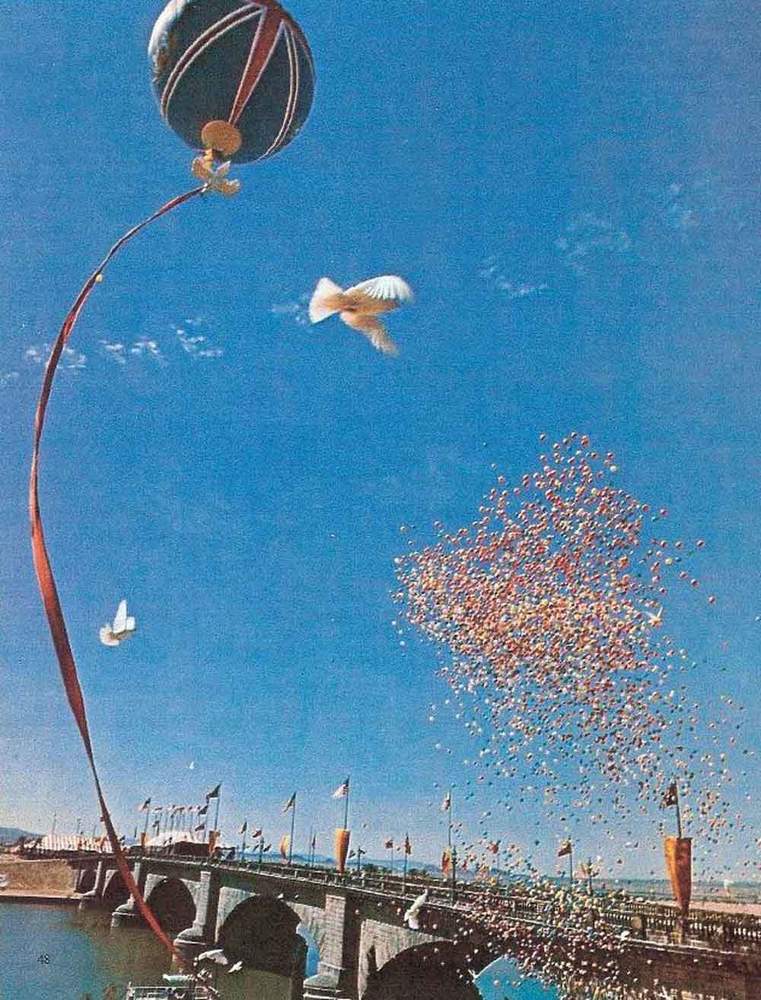

“I remember them releasing the birds and they had a big hot-air balloon with the British flag on. It was breathtaking - such an exciting thing to be part of.”

There was a party atmosphere as the anticipation built

According to a report in the Lake Havasu City Herald at the time, some 50,000 people lined the roads to watch the celebrations.

The gala featured a float-filled parade and the dramatic release of 30,000 balloons and 3,000 birds, to a backdrop of “home at last” which had been scrawled across the sky.

The dedication day festivities were an explosion of colour

Bobbi Holmes performed in the opening ceremony - an experience, she jokes, that scarred her for life.

“I was a member of the pom-pom girls and we did a dance. We were carrying these pom-poms and doing this routine and my arms felt so heavy. I thought, ‘I never want to be in a parade again’.

“But it was really fun and people came from all over. The English Village reminded me of Disneyland, which I later realised was because CV was behind it.

“It was pretty, sparkly, clean, with beautiful flowers. It was kind of magical.”

On 10 October 1971, Lake Havasu’s London Bridge opened to great fanfare.

The British were out in force, represented by a delegation from London accompanied by a troupe of red-jacketed horse-riders trotting through the desert.

Riders on horseback made a strange sight against the desert backdrop

The English Village offered a taste of home with its red phone box, double-decker bus and pub serving Yorkshire pudding and roast beef.

But the jewel was the bridge, with the British and US flags flying down both sides.

Rick Kingsbury’s Polaroids showed the scale of the event

“The whole place was just buzzing,” says Norma Grzesiowski.

“They had a big tent down there on the bridge and lots of events and games going on.

“I remember them releasing the birds and they had a big hot-air balloon with the British flag on. It was breathtaking - such an exciting thing to be part of.”

According to a report in the Lake Havasu City Herald at the time, some 50,000 people lined the roads to watch the celebrations.

The gala featured a float-filled parade and the dramatic release of 30,000 balloons and 3,000 birds, to a backdrop of “home at last” which had been scrawled across the sky.

There was a party atmosphere as the anticipation built

Bobbi Holmes performed in the opening ceremony - an experience, she jokes, that scarred her for life.

“I was a member of the pom-pom girls and we did a dance. We were carrying these pom-poms and doing this routine and my arms felt so heavy. I thought, ‘I never want to be in a parade again’.

“But it was really fun and people came from all over. The English Village reminded me of Disneyland, which I later realised was because CV was behind it.

“It was pretty, sparkly, clean, with beautiful flowers. It was kind of magical.”

“Everyone came out,” says Joni Echelberger, whose family had not long moved from Illinois.

“My aunt and uncle got to have the $100 dinner in the big tent and I was so jealous because I wanted to be in there.

“We were outside waiting and waiting and waiting for the fireworks and they wouldn’t go off until the celebration was done [so] they didn’t go off until midnight.

“For such a small community, it was really a big deal.”

A long red carpet led to the huge striped tent

Joe Hunnicutt remembers a “crazy” day that was bursting with community pride. But he tells a different story about those birds, claiming McCulloch hadn’t been able to find doves as planned. Instead, he mainly settled for pigeons.

“I remember standing there with my dad and he was wearing his blazer and tie, smoking a cigar, and he says, ‘You know, I think McCulloch is going to regret this particular decision.'

“And since 10 October 1971, Lake Havasu City has been infested with pigeons.

“They’re the joke and scourge of the town; you can’t get rid of them.”

Six years later, McCulloch died from an accidental overdose of alcohol and pills.

His death was keenly felt in the community he had built, where his legacy is remembered with a bronze statue and a road bearing his name.

Early West, who worked for him for 40 years, describes him as a man who “thought number one about his employees” and remained down to earth.

A statue of McCulloch and Wood stands at one end of the bridge

“Bob was a rich man, but he was pretty common,” the 86-year-old says.

“Ordinary people live on a certain level, and he didn’t get too much above that.

“I never noted him putting himself above anyone else.”

Early West was convinced by McCulloch to move from the entrepreneur’s LA factory to Lake Havasu

Fifty years on and people are still poking fun at McCulloch’s dream. At this year’s Academy Awards, host Jimmy Kimmel made a jibe about Lake Havasu while encouraging Oscar winners to keep their acceptance speeches short.

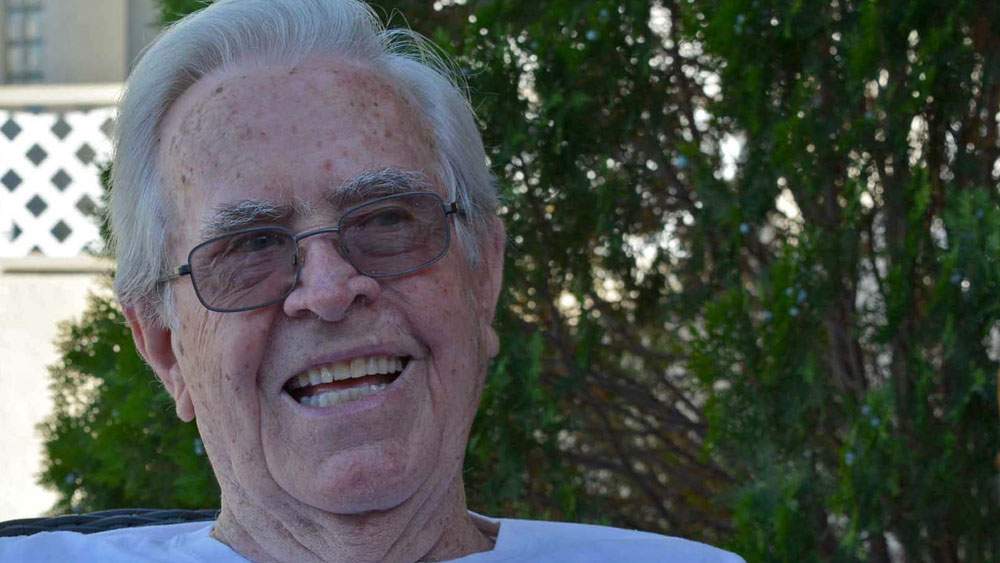

His gag actually caused a surge in interest in the resort - not that it really needed the help. According to the state tourist board, 3.65m people visited London Bridge in 2017 - making it Arizona’s third most popular attraction after the Grand Canyon and the Glen Canyon national parks.

Thousands of tourists have pierced a map in the visitors’ centre with pins marking their home state

McCulloch’s grandson Michael says people come because they’re "curious".

It’s a word that sums up Lake Havasu perfectly.

Driving in from Highway 95, the billboards scream “Visit the home of the London Bridge”. Before long, a flash of blue appears - not a desert mirage, but the waters of the Colorado River filling the city’s man-made lake up ahead.

Then before you know it, the bridge appears, dominating a landscape peppered with fast food outlets, hotels and palm trees.

It’s a surreal moment, even though you’ve been warned what to expect.

For the 52,000 residents that call Lake Havasu City home, the bridge is just a part of everyday life, providing the only access to and from the marina and the homes perched on the first spit of land purchased by McCulloch back in 1958.

And although the whole project cost about $12m, McCulloch is said to have recouped his costs before the last brick had even been laid in its new home.

The English Village was recently refurbished after standing derelict for years

Today, the resort thrives not just on tourism from the bridge, but from income from water sports enthusiasts and college kids on spring break. The calm lake and sunny weather have made the city a legitimate holiday destination - an outcome even its founder would probably not have predicted.

That a sinking bridge in London would be the making of a city in Arizona is a testament to McCulloch. But that it became such a success is down to boldness, determination and belief - a reflection, perhaps, of the American spirit.

Michael McCulloch says Lake Havasu was his grandfather's "pride and joy"

“The bridge changed things immensely, I don’t know what the city would be like if it wasn’t here,” reflects Michael.

“It was [supposed to be] a retirement resort but it’s turned into a sustainable economy and a lot of people are born here and have chosen not to leave.

“I think RP would be amazed by that.”