This article contains graphic accounts of violence.

There is a moment in the journey into Raqqa when you leave the real world behind. After the bombed-out Samra bridge, any signs of normal life vanish.

Turn right at the shop that once sold gravestones - its owner is long gone - and you are inside the city.

Ahead lies nothing but destruction and grey dust and rubble.

This is a place drained of colour, of life, and of people. In six days inside Raqqa, I didn’t see a single civilian.

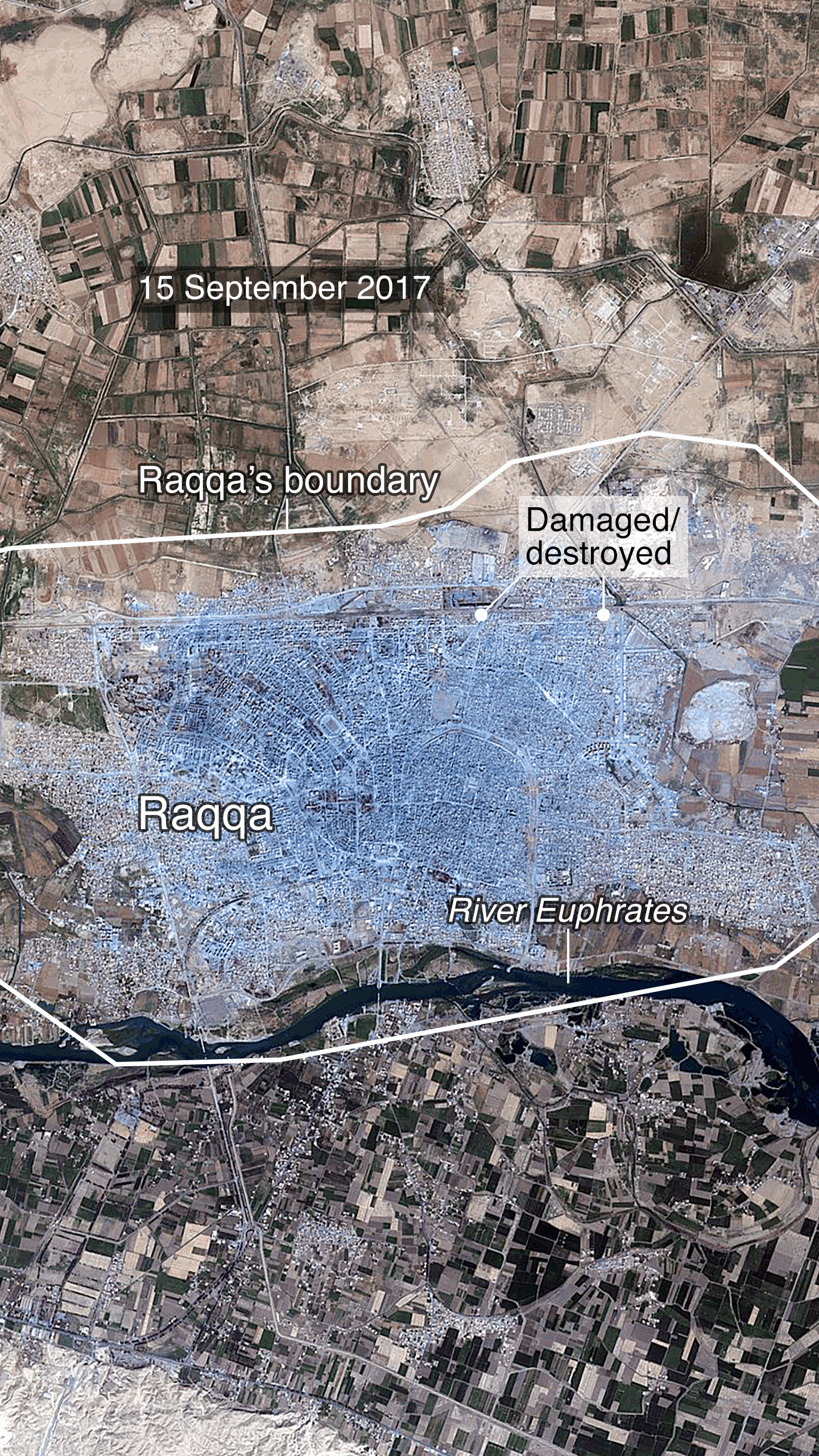

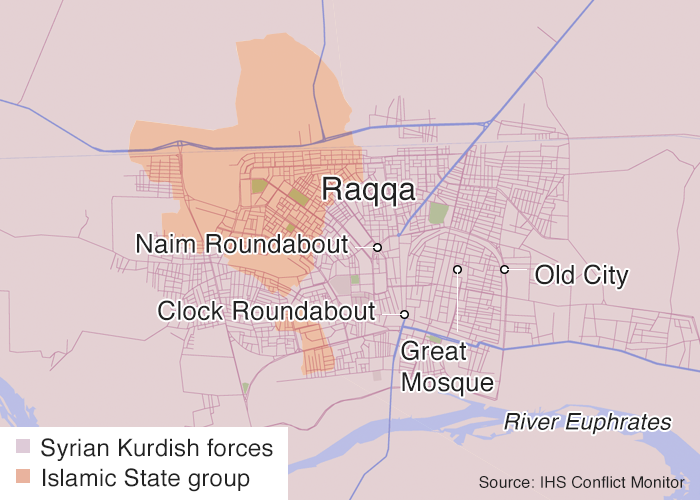

Control of Raqqa as of 25 September 2017

They are somewhere inside, trapped by the so-called Islamic State and the Western coalition’s bombing campaign.

IS uses them as human shields, and as bait, to lure out the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF).

It seems that not a single building has escaped the onslaught. Many have been crushed, flattened, or knocked to one side by the Western coalition’s air strikes and artillery.

It is a barrage that never ceases. More than two dozen air strikes a day, and hundreds of shells fall on the city.

Their target is the last men of the Islamic State. There may be as few as 400 left.

SDF fighters

The SDF, which is made up of Kurds, Arabs - Muslims and Christian - and Yazidis, among others, has been making good progress since the offensive began in June.

It has IS surrounded. And with Western air power pounding from above, its front-line advances are chewing through neighbourhoods.

It is only a matter of time - perhaps a month, maybe two - before IS in Raqqa is swallowed whole.

This was the capital of the Islamic State’s unrealised caliphate. It was home to half a million people.

But now it is fit for no-one. IS is already making propaganda capital out of the destruction.

America says this a war of annihilation. Raqqa is the battleground and the victim.

The Islamic State was a spectre of terror that had taken over our lives for four years. We grew tired and we despaired. Life had stopped. The only escape was to drown ourselves with work.”

Hatem (not his real name), a shopkeeper in his early 30s, is one of the several hundred civilians who, in mid-August, took the risk and escaped a city plunged into death and destruction.

When the SDF announced the Raqqa operation, Hatem says the people of the city were happy, if apprehensive, about the Kurdish role.

However, the news coming from SDF-controlled areas was encouraging.

“We heard about Tal Abyad becoming relatively stable. Prices of basic staples and foodstuff were decreasing. A barrel of diesel in Tal Abyad dropped to 12,000 liras (£15). In Raqqa it was nearly quadruple that,” the shopkeeper says.

But it was the participation of the US-led coalition that the people of Raqqa were most excited about.

The advanced weaponry, they thought, would spare them the grind of the urban warfare IS had been preparing for.

“When a coalition air strike took out that French jihadi near the Clocktower Roundabout, I went shortly afterwards to check the scene,” Hatem, whose shop was near the drone strike, says.

“He’d been consumed by flames in his own car. No-one else was killed. There was no shrapnel damage to be seen. We were excited because we thought it was this technology that the USA was bringing into the fight.”

Destroyed street in Raqqa's Old City

But the excitement was short-lived, as displaced people from the city of Tabqa started flooding into Raqqa.

Tales of an “indiscriminate” bombing campaign, flattened buildings and hundreds of alleged civilian deaths rattled the local population.

In June, Raqqa’s siege was completed and the US campaign was in full swing. Civilians were trapped inside with IS fighters.

“America is a superpower. It was supposed to use laser-guided bombs and precision munitions. What did we get instead? Massive bombs, mortar rounds and countless artillery strikes. Is that how you liberate Raqqa? You’re murdering civilians instead,” Hatem says, his voice now quivering with a mix of anger and despair.

Airwars, a group monitoring civilian deaths in Russian and US-led coalition air strikes Iraq and Syria, says that US-led forces dropped 5,775 bombs, shells and missiles in Raqqa in August alone, resulting in at least 433 likely civilian casualties.

Ahmad, a Turkey-based Raqqa activist has documented the deaths of at least 750 civilians in the city since June - 520 of which he says were in coalition air strikes. Airwars, on the other hand, says at least 1000 Raqqawi civilians have been killed since June.

The coalition has conceded four civilian deaths during the battle for Raqqa. It says it has adhered to strict targeting processes and procedures aimed to minimise risks to civilians.

As ever, the Islamic State group was quick to use civilian deaths to its own advantage and pumped out one propaganda video after the other showing burnt corpses and maimed civilians.

Lawyer Obeid Agha al-Kaakaji became the face of his bloodied city.

With a deep gash across his forehead, Obeid’s face appeared caked with blood and dirt. His thick white hair and long beard were stained brown.

The white of his eyes had disappeared behind a disoriented, tormented gaze.

He was once a proud lawyer, known across the city of Raqqa for his philanthropy and concern for the downtrodden.

Obeid Agha al-Kaakaji as a younger man

“As a lawyer, Obeid was the caretaker of the family’s assets and wealth in Raqqa,” his Saudi-based relative Hani tells the BBC. “When the siege closed in during Ramadan, he refused to leave, preferring to help people in need.”

The BBC tracked down a former neighbour of Obeid. Ziad (not his real name) witnessed the coalition air strike that hit the al-Kaakajis’s house.

According to Ziad, IS fighters had commandeered the house during the last week of June and set up a camouflaged mortar position in the courtyard.

“They hid it right under the tree. They used to come every couple of days and fire a few rounds towards the east of Raqqa,” he says.

“We tried to talk them out of it but they got angry and accused us of being apostates.”

On 22 July, at about 10:30, a coalition air strike targeted Obeid’s house as Ziad was coming to visit the family for their usual morning chat and coffee.

Obeid Agha al-Kaakaji before it was bombed

That day, IS fighters hadn’t shown up to man the mortar, he says. “Just as I was about to knock on the door, I heard this terrifying noise and then everything turned black. It felt like a hurricane had picked me up and slammed me into the wall behind. I tried to run for cover, but then that’s when the second missile struck,” Ziad says.

Lightly injured, but severely bruised, he picked himself up and headed towards the rubble to help survivors. He recognised his other neighbour, Abdellatif al-Sheikh, but he was already dead.

A relative of Obeid’s, I’tidal, was in agony.

“She was lying there, her legs contorted, mangled. She was begging me for help. I can still hear her whimpers asking for help. But I couldn’t do anything. She died there,” Ziad says.

Six people survived, Obeid among them.

He was right outside in the courtyard when the missiles hit.

Obeid Agha al-Kaakaji as an older man

A wall had collapsed on to him. Ziad says the lawyer didn’t look seriously injured, only “dazed and confused”.

He transported him to an IS-run hospital in the west of the city.

“They only tend to their own. As soon as they realised the injured person is a civilian, they stop caring. His injury becomes the lowest of their priorities - even if it’s life threatening,” Ziad says.

Obeid, with his lost and haggard look, quickly came to the attention of the IS propagandists. But he was soon discarded.

His condition started deteriorating the second day. An internal injury was suspected. Three days later he died, untreated and uncared for.

Ziad is still angry about that day.

“We know that for IS, the blood of civilians is very cheap. But is it the same for Americans? There was no-one operating the mortar that day. There were no IS fighters nearby even. It was there for nearly a month and their drones were flying night and day. Why bomb us? Why?”

His question may never be answered.

If you experience problems with this video you may want to change your browser.

For Hatem, the shopkeeper who was excited about the US-led campaign, Raqqa was fast becoming a death-trap. At first, people he didn’t really know were being killed.

But as time went by, acquaintances, friends and relatives were dying.

“There were 20, 30 civilians being killed every day. People were getting buried under the rubble of their own homes,” he says.

Islamic State fighters, he says, were getting aggressive with the locals. At one point, they stopped sending bulldozers and trucks to move the rubble and rescue civilians.

“They’d ask, ‘You want me to sacrifice the life of a brother for a corpse?’ How can you argue with animals like that?”

One day in early August, stuck at home with no electricity and nothing to do, Hatem began counting incoming thuds and bangs.

“I started at 10 in the morning. By seven in the evening, I had counted more than 290 explosions. The bombing was becoming relentless.”

And so he began plotting his escape.

For the next 10 days, he began monitoring the route he planned to take, where IS had laid mines and at what time there were fewer fighters around.

He chose to go south, past the Intercity bus station, past the Central Bank and to the bombed out Old Bridge.

A date and time were chosen, and close-knit friends and family were asked to join.

In the early hours of 12 August, under a Moonless sky, a group of 40 people had gathered near the Clocktower Roundabout to embark on their perilous journey to safety.

“We took that chance because we all felt that to stay in Raqqa would be our death sentence,” Hatem says.

“We set off at 02:55. We had elderly and disabled people among us. It took us nearly 90 minutes to walk one mile. By 04:30, we reached the bridge and stayed under its ramp,” he says.

Had IS caught them, they would have been executed.

“At the first break of light, we started moving again waving a white flag. The SDF saw us and sent us boats to take us to the other bank,” he says. Hatem sent word to another group waiting to take the same route.

Out of the 302 civilians who set off the following night, 12 died stepping on IS mines.

For Hatem safety came at a price. The SDF detained the men and started asking them about IS positions in the city.

“We left 5,000 civilians behind,” he says. “Those positions are hidden in built up areas where our friends and relatives still live. Are they going to bomb them?”

Asked whether he did reveal the positions, he replied: “I can’t go on remembering any more. This is very painful. I have to go and have some coffee and a cigarette.”

Abu Abdo drives around central Raqqa in an armoured car that once belonged to Islamic State fighters. It's as ugly as it's uncomfortable.

The unit’s Humvee is in for repair, after IS, in a common tactic, shot out the radiator. Also, Abu Abdo complains, the air conditioning doesn’t work.

There is only one seat inside, the driver’s, and it is reserved for the Arab SDF commander.

Abu Abdo is from Manbij in northern Syria, he is 24 but looks decades older.

Abu Abdo at the wheel

His unit is small, a ragtag bunch fighting in sandals and using Chinese-made AK47s.

Almost no-one has a complete uniform. They are a militia, not an army. But they work well together, coordinated and fearless.

Some of the fighters are very young. I ask one how old he is. He smiles and shakes his head. Like many young men and boys here in Raqqa, he knows not to answer.

Abu Adbo hunches over the steering wheel, his beard almost touching the wheel.

You can see some (IS) bodies here.”

He points them out like a tour guide as the vehicle trundles along.

The streets are strewn with rubble, but bulldozers have cut a path through the debris. There is no sign of life anywhere. The only sounds are shelling and sniper fire.

The homemade armoured vehicle is hot and noisy inside, riding in it is like being rolled down a hill in an oil drum.

“We got this vehicle when we attacked a Daesh [IS] base,” Abu Abdo says. “We attacked them suddenly. They had no time to take their armoured vehicle, so now it belongs to us.”

I ask if it is wise to ride around the city in an IS vehicle with coalition aircraft and drones overhead?

Abu Abdo

“Before we go out we inform the operations centre and we tell that this vehicle is ours,” he says.

“And we have a flag on the vehicle, a Syrian Democratic Forces flag. The jets can see that this belongs to us,” he adds.

As we rumble along, I point out that there is no flag on the vehicle. He pauses for a moment, and then remembers: “We stopped there earlier and our men took the flag off.”

He radios ahead to the next checkpoint to warn of our arrival.

He takes us to a high building, near Naim roundabout, at the city’s centre.

This is the edge of IS control, the front line.

The vehicle lumbers across a street watched by IS marksmen.

Abu Abdo wants to get as close as possible so that it is safe to get out. He misjudges and crashes with a loud thud into a pillar.

I worry that the building, already half destroyed by coalition air strikes, will collapse.

We climb out and enter the building, a former private hospital. His men there have piled up furniture at the bottom of the stairwell, in case IS rush the building.

Further down the street, the black flag of the caliphate hangs from a building.

The day is hot and still and the flag doesn’t move. It’s easily within reach, but in the direct line of sniper fire.

For now, the SDF dare not remove it.

They are trying to take Naim roundabout, the centre of Raqqa, the heart of the caliphate.

It’s an important tactical point, overlooking many roads in an area that was full of shops, cafes and offices.

Now it is called the Circle of Hell.

The SDF has another reason for wanting to retake it, there their comrades and friends were crucified and beheaded by IS.

When the roundabout falls, they say, they will truly cleanse Raqqa of the murderous Islamic State.

IS fighters have mined the buildings and the roads, so few have been cleared.

They’ve left motion sensors in some buildings so that when SDF forces enter, or open a cupboard door, a bomb detonates.

Every home and workplace has been damaged. Even a captured IS weapons store has been left untouched for fear of booby traps.

Abu Abdo shows me a camouflage balaclava, it’s one of the few things they retrieved from there.

Their snipers have control of the rooftops. Keep your head down.”

A call comes across the radio. One of his fighters has been shot and is trapped in a nearby street.

When we get there the man can’t be reached. He has been hit in the chest.

IS snipers are firing at the end of the street, and Abu Abdo’s men are pinned down.

They are desperate to get to the injured fighter, but every time they move closer, more shots ring out.

Suddenly there are two big explosions nearby. IS has dropped grenades from drones. The SDF fighters run and take cover in nearby shops.

Abu Adbo pulls out his walkie-talkie, and looks at his phone.

He calls up a map of the street and reads out the coordinates. He looks at me. “Air strike,” he says. Everyone is told to take cover.

Abu calls in an air strike

The injured fighter, his name is Nadin Abu Aziz, is still trapped on the road. He isn’t moving.

I duck into an electrical shop, its shutters have been forced open. It’s quiet outside, as the men wait patiently for coalition aircraft to take out the IS gunman.

We hear warplanes fly close and low, but no bang. The SDF fighters continue to wait. There’s no sign of life from the trapped fighter.

Inside the electrical shop, there is a man-sized hole in the wall. A pneumatic drill lies on the floor. Through it is another store, and a stockpile of bottled water, and food. There’s enough to last a year.

Beyond that, another gap in the wall, into another building, and a room with a bed, a stove and a motorcycle.

This was an IS hideout.

Is hideout

It spans three buildings and the IS fighter would have been able to have access to all the floors above including the roof.

IS has created thousands of these firing positions across the city. Mindful of IS booby traps, I don’t explore any further.

Outside I can hear coalition jets flying low and close.

The strike hits the targeted building precisely. Like the others in the street, it is a ruin.

Time and time again, entire buildings are taken to kill a single fighter.

It’s unsurprising so little of Raqqa is left. The SDF lacks the manpower to clear buildings themselves, so coalition bombs do the work.

A thousand coalition sledgehammers, smashing down on a nut, building after building, street after street.

The IS gunman is no longer shooting, he’s either dead or gone.

SDF fighters rush to Nadin Abu Aziz, they pick him up and awkwardly place him in the back of the former IS armoured car.

His eyes are closed, and it looks like the IS marksman shot him in the chest.

When Abu Abdo returns with the news that Nadin is dead, no-one is surprised, but still they stop, stare and fall silent.

One young fighter takes a crucifix from under his shirt and holds it while mumbling a prayer. Another crouches down in the street and says nothing.

The Sun is beginning to set and the men are exhausted.

But this is not an unusual day, says Abo Abdo, shaking his head.

Yesterday we were supposed to receive some civilians but one of us was killed. We went to help families and babies, and one of us was shot in the head.”

IS fighters were hiding, in disguise, among the civilians.

“They attacked us with their men dressed as women, and there were big numbers, like a hundred,” he continues. “We guessed that they were civilians, and they also had children with them, and suddenly the civilians and children went to the side of the road, and then they started to fire at us”.

Civilians in Raqqa, there may be as many as 20,000 in IS territory, are used as bait as well as human shields.

“We’ll keep going,” says Abu Abdo. “We will sacrifice our blood for Raqqawi’s and our people inside, because they are having a tough time, a really tough time.”

Raqqa is the doomsday city.

Danger lies around corners and in the shadows. It comes from distant snipers, hidden bombs, and the deep tunnels that riddle the city.

Even in areas that have been secured, IS can sneak back under the cover of darkness.

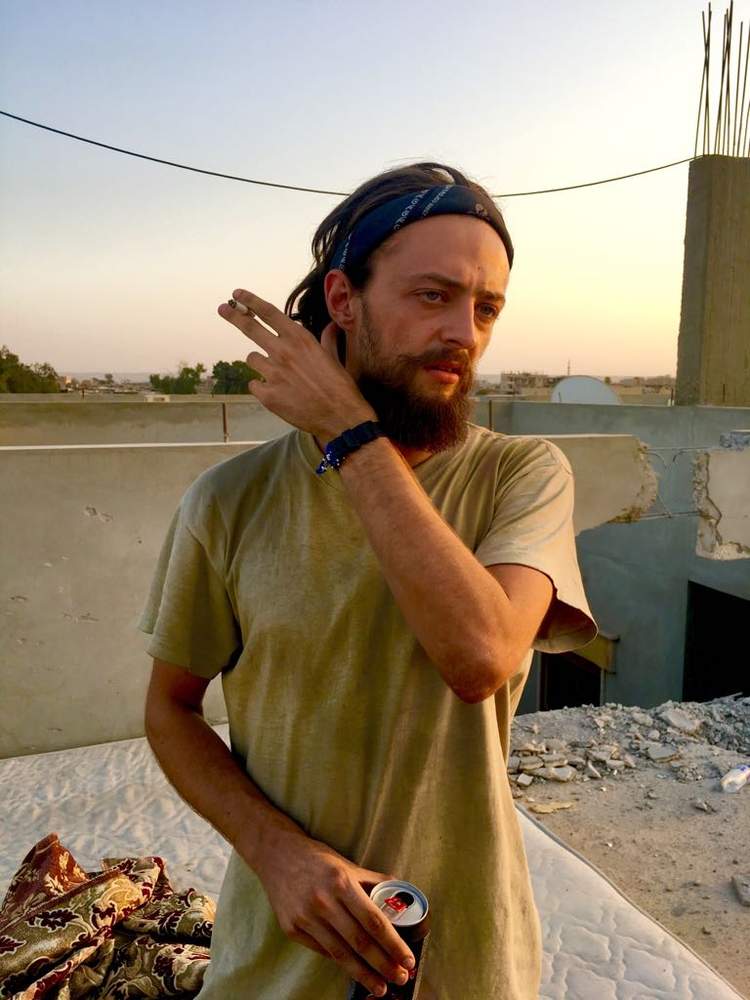

The SDF has its own sniper unit. Four foreigners, from Germany, Spain, the US and the UK.

A month ago, they were holed up in the old city, near the top of a building. It was getting dark, they were looking for any movement.

They would wait for hours, then a shot would ring out - hopefully a kill.

“We’re always on the offensive,” says Jac Holmes, from Bournemouth. “Daesh are always defending so they’ve always got the advantage. This has been their city for however many years now so they know it better than we do. It’s been very hard.”

That night was particularly hard, the foreigners smelt smoke in the building.

“Daesh have worked out how to start fires very quickly, they creep inside the building and try to smoke us out,” Jac says.

They could hear the IS fighters moving, as the smoke grew thicker, they began firing downstairs. It was their only way of escape, but IS was waiting. They were trapped.

But Jac and his unit had earlier found two IS suicide vests.

They were rigged with detonation cords, like grenades. They pulled the cords and threw both vests downstairs into the smoke and the darkness.

The explosion shook the building, Jac, says. “We don’t know how many we injured, they were all gone when we went down. The explosion was so big it put out the fire.”

I first met Jac two years ago near the Turkish border.

He was in hospital then, with a bandaged arm. It was an IS gunshot wound. He giggled about it at the time, appearing ill-equipped to be taking on IS.

Before Syria, he had worked in IT. I wondered at the time how long it would be before he was killed.

Jac has changed. The giggles are gone, his hair is longer, and he has a thick beard. He’s grown in stature.

He won’t discuss how many IS fighters he has killed. “Why does everyone ask that?” he asks.

But what is it like to kill a man?

“You feel nothing,” he says, then pauses, “you feel excitement.”

His weapon is an M16 with a large scope. It isn’t ideal, but Jac says: “We are never that far away from them, maybe 400m [1,300ft], it’s very close on the front line.”

Jac's M16

His wage is $100 (£75) a month.

He’s ambivalent towards the socialist ideology of the Kurds. Anything he needs, from food to clothing, is given for free. The $100 keeps him in energy drinks and cigarettes.

His one credo, though, is his hatred of IS.

The are a barbaric fascist terrorist organisation who essentially want to take over the world. If you don’t comply by their rules, they will kill you. It’s as simple as that.”

There are fewer direct attacks and car bombs in Raqqa than there were in Iraq’s Mosul.

Here, it’s the snipers and the roadside bombs that do the work. Mostly, IS doesn’t move, but lies in wait.

As the men and women of the SDF’s Kobane brigade prepared for an operation near the city’s grain silos, they knew all of this, but still there will be surprises.

Some look as young as boys.

Barely hair on their top lips, they sit and load their magazines with ammunition.

When I ask their age, they shake their head and smile.

They know not to answer. Many of them are teenagers.

The commander is Shevgar Himo. He has just celebrated his 24th birthday inside Raqqa.

He’s half Arab, half Kurd, and is rarely without a tablet computer or new Samsung smartphone.

Supplied by the Americans, they plot the IS retreat.

His men are assembled, ahead lies a residential street, every house bombed, and IS still heading in the ruins.

The target is the city’s grain silos, long held by IS and key ground because it gives the militants a high position over this part of the city.

Shevgar Himo

Shevgar Himo says: “The bulldozer is opening up the roads and the armoured vehicle is following behind. We are going to clean that area, then we will reach the other group of SDF that is attacking from the other side.”

IS will be squeezed between the SDF forces.

Immediately, the SDF take incoming fire.

But they keep in formation and ensure their fighters don’t bunch together. That would only invite a rocket attack from IS.

One by one they cross open streets, under fire.

IS bullets zip past, missing the heads of the fighters by only inches.

Armoured bulldozer

At first things go to plan. Then comes the first surprise.

IS snipers are good. The armoured bulldozer is covered in bullet holes, including right in the centre of the windows of the operator.

But IS knows where to hit.

I hear a couple of shots ring out. They’ve taken out the bulldozer’s radiator, it’s leaking fluid and needs to leave to be repaired.

The second bulldozer goes in, there’s another shot, and a "whoosh" of escaping air.

The IS sniper, hidden and invisible to the fighters, has shot off the valve on the tire. The fighters stand around and marvel at the accuracy of the shot.

Bulldozer number two is now also out of action. So the fighters try a different approach.

In minutes, at the end of a street, they plan a movement, half a dozen of them, including one armed with a rocket propelled grenade, to take out a sniper near a mosque.

There Kurdish and Arab fighters work well together, but there are moments of confusion.

One Kurdish commander doesn’t speak Arabic, his Arab counterpart speaks no Kurdish.

It takes a third person to translate.

When I ask some of the fighters where they are from, they reply with a vague “Rojava”, the Kurdish controlled area of northern Syria. But it seems they are not local.

The suspicion is that some of the best fighters here are PKK, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party.

Loathed by the Turkish government, it is also designated a terrorist organisation by the West.

But here in Raqqa, they are some of the most effective ground troops in the battle.

The fighters at the end of the street launch their attack on the sniper position, the noise is deafening, and the firing barely ceases for a second.

Under the cover of fire, the fighter with the RPG, runs into the middle of street and fires at the IS position.

Some more gunfire, then silence.

But as I turn the corner to leave to get into the armoured vehicle, the sniper opens up again.

About half a dozen shots, I hear them whistle past me, two smack into the wall. No-one is hurt.

A boom of an air strike rattles the street and the sniper is finally killed.

All of this for barely half a mile of street, but the fighters are closer to the silos now.

The next day, they take them and a large swathe of Raqqa is back under SDF control.

IS had promised to grow a new empire from these streets. Instead, the bodies of its fighters clog the gutters.

Every few hundred metres, there is another one. Some cut in half, some still with their weapons.

Two men were hiding in a building doorway, but they were spotted.

They lie dead where they stood, one, his legs sliced from his body.

The fins of the missile that killed them stick out of the concrete pavement. There are scorch marks at the building's entrance.

An Arab fighter, with a skull and crossbones patch on his uniform, steps over the bodies, he has to check the building for booby traps.

As he passes the dead fighters, he greets them, wryly: “Allah, bel kheir [May God make your evening full of good].” The fighters around laugh.

The SDF forces document each corpse on their phones and tablet computers.

They think it is mostly foreign fighters left inside Raqqa now. When I ask how many, most seem to agree: 400, no more.

A tiny number making a last stand, but holding the might of the SDF and coalition at bay, and ensuring that what’s left of Raqqa continues to be destroyed.

For four months Raqqa has been the battleground in the war of annihilation against the Islamic State. It is also a victim, broken and barely alive.

The map on the SDF commander’s smartphone has a red square, it slopes at the bottom, passes Raqqa’s stadium and hospital and extends a few kilometres north.

It’s all that’s left of IS territory.

It’s in this area - little more than five sq km (1.9 sq miles) - where the battle for Raqqa will end.

The Kurds are confident of victory. Already they are sending fighters to another front with IS, to the city of Deir al-Zour, further south.

Air strikes inside the red box have lessened in recent days. It’s where most civilians remain.

Jac Holmes, the British SDF sniper, is in no doubt the air power was necessary.

“It’s made a huge difference. I mean, without them we would never have got this far. Let alone take Raqqa”.

The Islamic State’s remaining fighters are said to be mostly foreigners, from central Asia, they have no love for the city, nor its people.

They’ll gladly see it destroyed.

It serves their propaganda purposes too. Here, they will say, Western bombs destroyed an ancient Arab city.

If you experience problems with this video you may want to change your browser.

In nearby Tabqa, I met Ismail Al Ali.

“Raqqa’s citizens have paid the price,” he says in broken English. “Their city is destroyed. Raqqa has paid the price for all the world”.

Nearby, a grandmother wipes her tears with her headscarf and says: “We left our beloved people, our children, everything behind, we know nothing about them. We only need to go back to Raqqa, we don’t need anything, we will stay in tents in the streets.”

They haven’t yet seen what’s left of their city.

When they do, they will likely ask, did so much of their beloved Raqqa have to be destroyed, so that it could be saved?