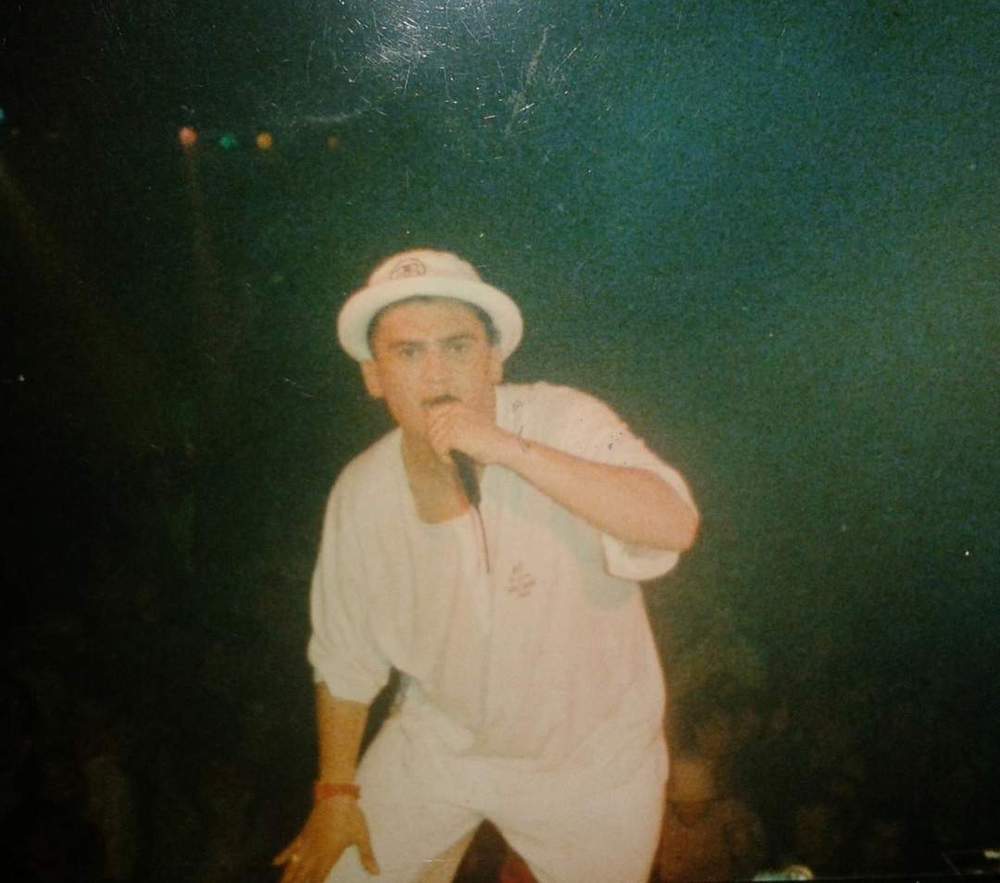

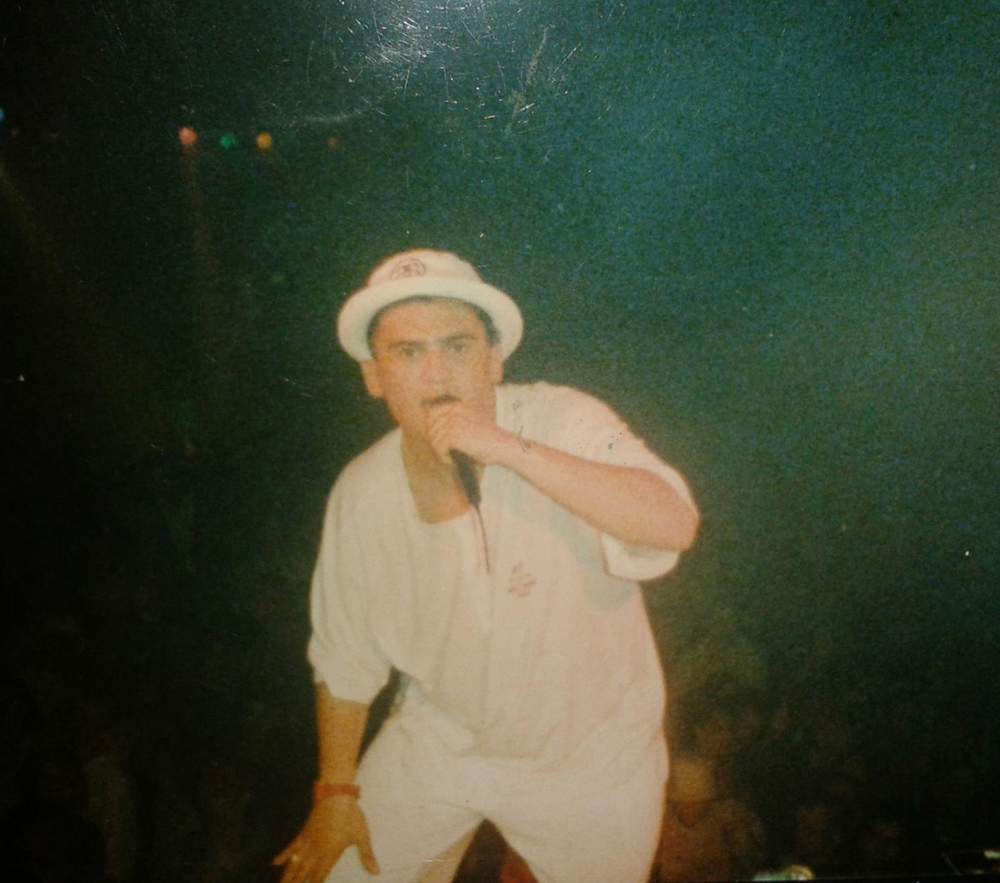

It was called the Second Summer of Love. It’s 1989. A new genre of music is sweeping through nightclubs across Britain. It’s reached the gritty, northern English town of Middlesbrough. The Havana nightclub is packed and bouncing. The synthesised beat produced by the Roland TB-303 Bass Line machine is vibrating through the walls. Clubbers are dazzled and blinded by strobe lights, disco balls and smoke machines. The Havana is like a furnace. Condensation is dripping from the ceiling; sweat is pouring down the clubbers’ faces. But they’re completely entranced by the music.

The scene is inspired by house music, a genre of electronic dance music pioneered in the US city of Chicago in the early 1980s. But it’s also being fuelled by the appearance of a little white pill: ecstasy. It’s illegal. Over the years it’s been blamed for many deaths. Its use sparks a moral panic across Britain. Headlines appear in the newspapers warning about the evils of ecstasy. But many of the clubbers at the Havana don’t care. It’s their drug of choice, creating a feeling of euphoria that lasts for hours.

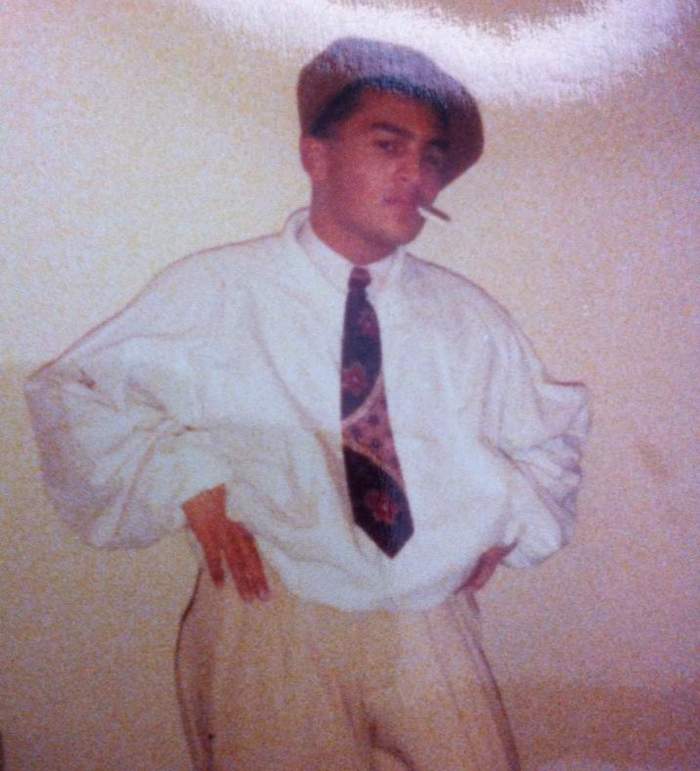

Dancing beside the DJ box is MC Hooligan X. Lee Harrison is a devilishly good-looking guy. It’s his job to whip up the crowd. He revels in it. He’s like a prince who has found his people. “You chill, I chill, on a pill. We all chill chill on a pill pill,” he raps into the microphone.

They called it the Second Summer of Love. It’s 1989. A new genre of music is sweeping through nightclubs across Britain. It’s now reached the gritty, northern English town of Middlesbrough. The Havana nightclub is packed and bouncing. The synthesised beat produced by the Roland TB-303 Bass Line machine is vibrating through the walls. Clubbers are dazzled and blinded by strobe lights, disco balls and smoke machines. The Havana is like a furnace. Condensation is dripping from the ceiling; sweat is pouring down the clubbers’ faces. But they’re completely entranced by the music.

The scene is inspired by house music, a genre of electronic dance music pioneered in the US city of Chicago in the early 1980s. But it’s also being fuelled by the appearance of a little white pill: ecstasy. It’s illegal. Over the years it’s been blamed for many deaths. Its use sparks a moral panic across Britain. Headlines appear in the newspapers warning about the evils of ecstasy. But many of the clubbers at the Havana don’t care. It’s their drug of choice, creating a feeling of euphoria that lasts for hours.

Dancing beside the DJ box is MC Hooligan X. Lee Harrison is a devilishly good-looking guy. It’s his job to whip up the crowd. He revels in it. He’s like a prince who has found his people. “You chill, I chill, on a pill. We all chill chill on a pill pill,” he raps into the microphone.

The crowd lap it up like a collective communion. They respond with shrill blasts from their whistles. Their ears are ringing, but they can’t get enough of it. Even when the police or fire brigade raid the club. “Old Bill, Old Bill,” raps Hooligan X. It’s a coded warning. The drug dealers peddling ecstasy scurry into the shadows and stash their supplies. The fire exit pops open.

There has always been a dark, sinister side to nightlife. “Everybody misses that time,” says one former regular at the club. “It was a feeling of being all loved up. But it became a very intimidating scene.”

This was the dangerous world Lee Harrison moved in all his life. But it would catch up with him more than 25 years later.

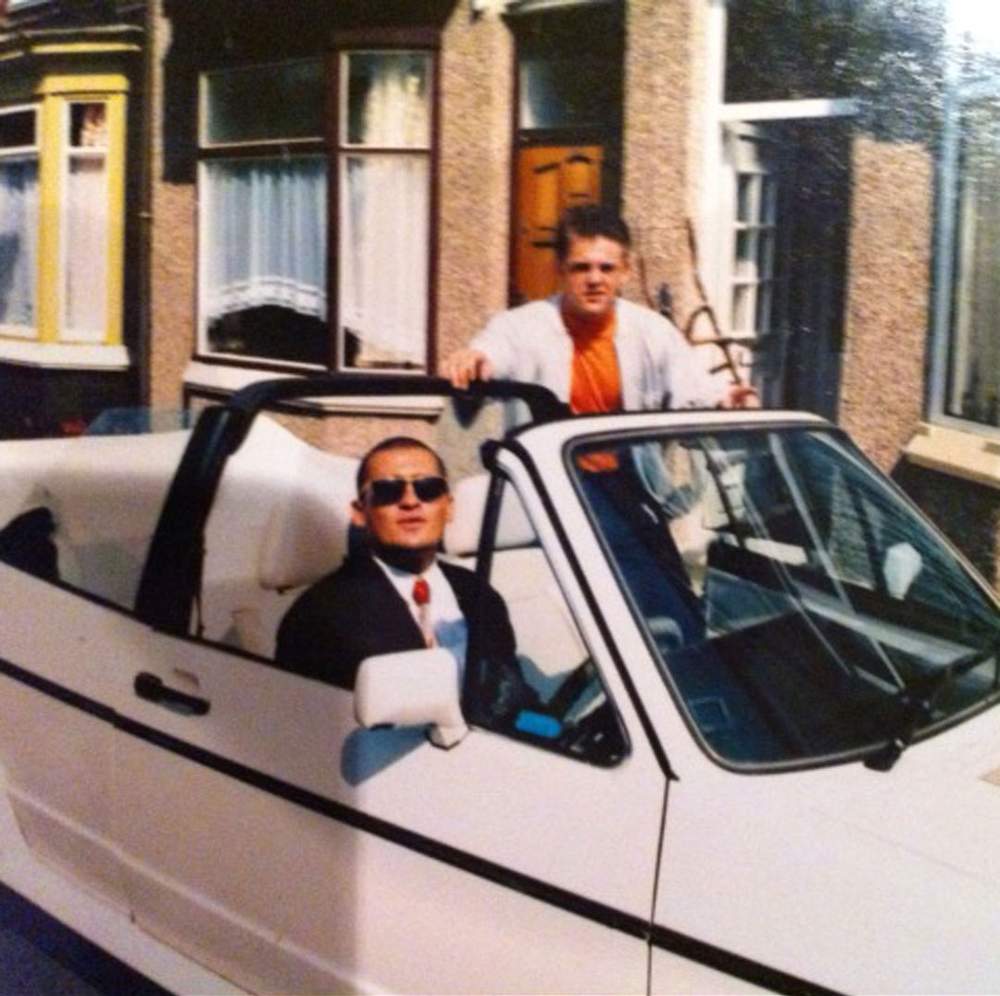

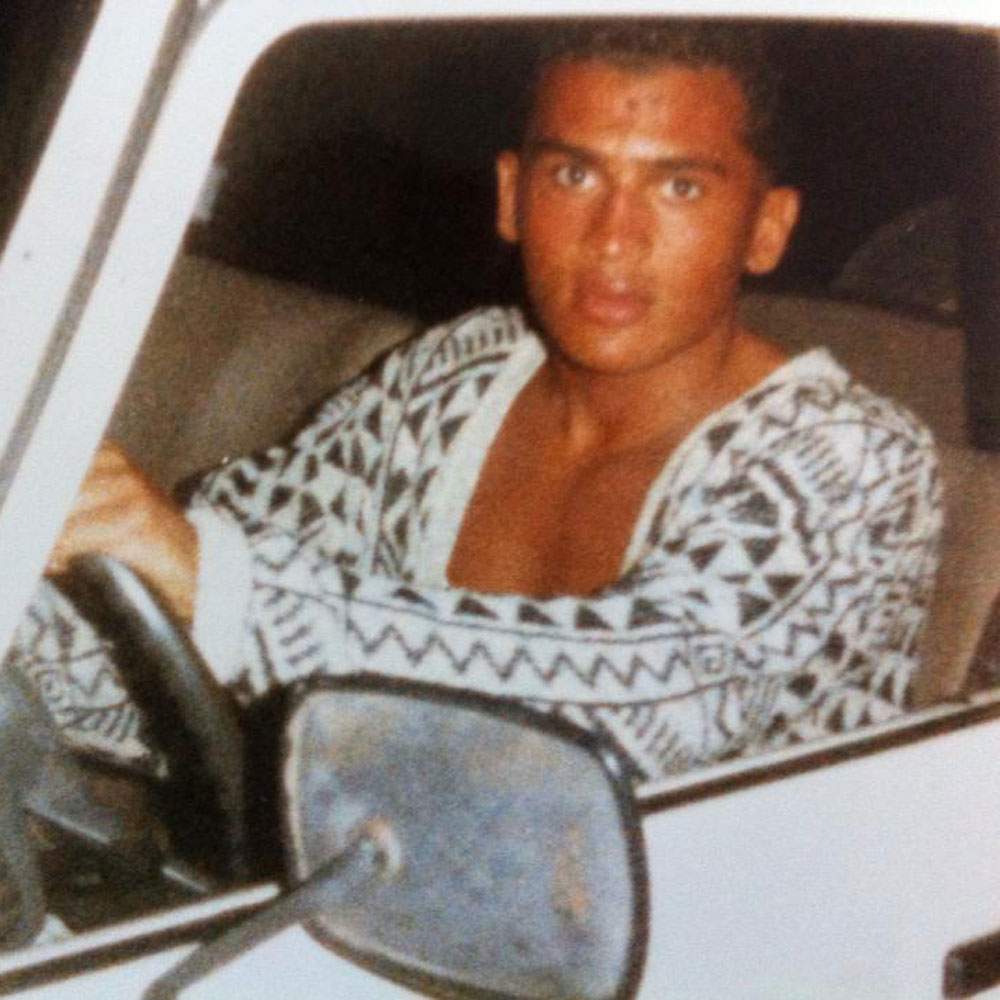

Lee Harrison was a face everyone knew around Middlesbrough. He was often seen bombing around town in his open-top convertible with the music blaring. “Lee would get where the wind doesn’t get but in a lovely cheeky way,” says his childhood friend, Alan Appleton. “He was a good-looking lad and could get any woman he wanted. You would see photographs of him with Mike Tyson and you would just snigger, ‘Yup, that’s the Lee we know’.”

But for all Lee’s charm, there was a violent side to him. Someone who knew him said he pulled a gun on him during an argument. A friend recalls Lee spiking his drink with hallucinogenic drugs for a laugh.

Lee Harrison and friend Lee Duffy, a former boxer, bouncer and gangster who was known as one of the most feared men on Teesside in the 80s

Lee Harrison was born on 8 March 1966. He was of mixed race. His mother was of Burmese-Portuguese origin. His father, Tom Harrison, is by his own admission an “old villain” who has spent much of his life cycling in and out of jail – including, he says, a 30-month sentence for conspiracy to supply drugs from Pakistan in the early 80s. But more about drugs later.

Lee grew up in the North Ormesby area of the town, which now has the enviable record of being one of the cheapest places to buy a house in the UK. During Lee’s childhood, it was a solid working-class neighbourhood where everybody knew everyone; where doors were left unlocked and children would play football or ride their bikes in the streets.

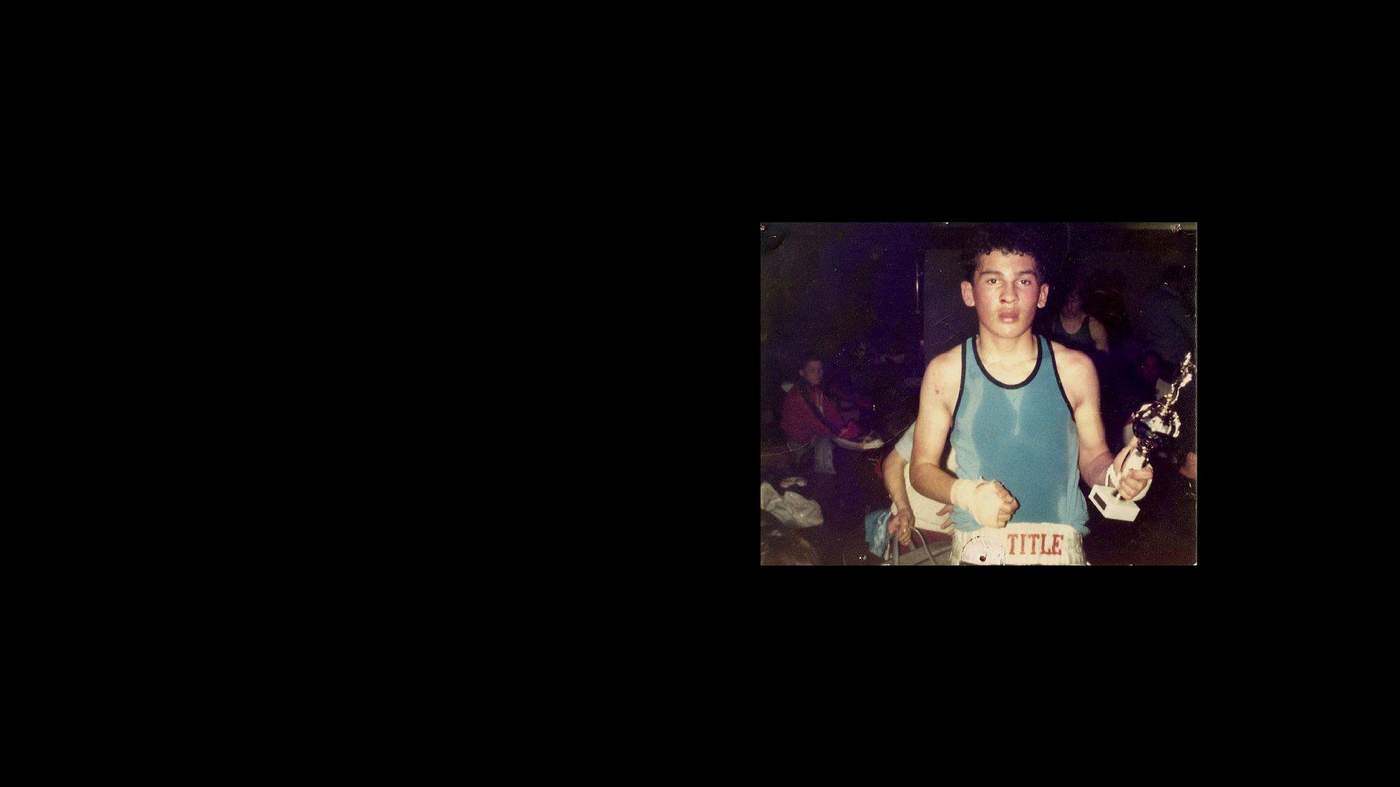

Lee was an excellent junior boxer. He was known for his looks and didn’t like getting hit in the face. Being handy with his fists came in useful a few years later when he got involved in football hooliganism. The Middlesbrough Frontline followed their beloved team around the country, fighting pitched battles against rival fans.

“We would get guys from all the nearby estates,” says Paul Slater, who was a member of the Frontline. “It wasn’t about the violence, it was about gaining respect for our hometown. Lee loved it. He loved the attention.” It was those bloody Saturday afternoons that inspired his MC name: Hooligan X.

Lee left school with no qualifications and immediately started helping his dad out in the “copying game”. At one stage it was mainly counterfeit clothing. “We used to get bundles of gear, tracksuits and trainers - that was the fashion then - and sell it all over the north-east,” says Tom. But they also had a sideline in fake Rolex watches and perfumes. “We’d get the bottles in Romania, the essence from France, and the boxes were made in Birmingham. It was all done professionally. It would cost you about two quid to make a bottle of Coco Chanel.”

It was a life of crime that paid for flash clothes, fast cars and fancy foreign trips. But music was always Lee’s passion. “As a six-year-old when we were invited to weddings, he’d be on the dance floor,” says Tom. “He was unbelievable.” Lee’s love of music was inherited from his dad. Tom ran the doors at the Speakeasy, a nightclub that later became the Havana, and had a huge record collection. The pair listened to reggae, particularly Bob Marley.

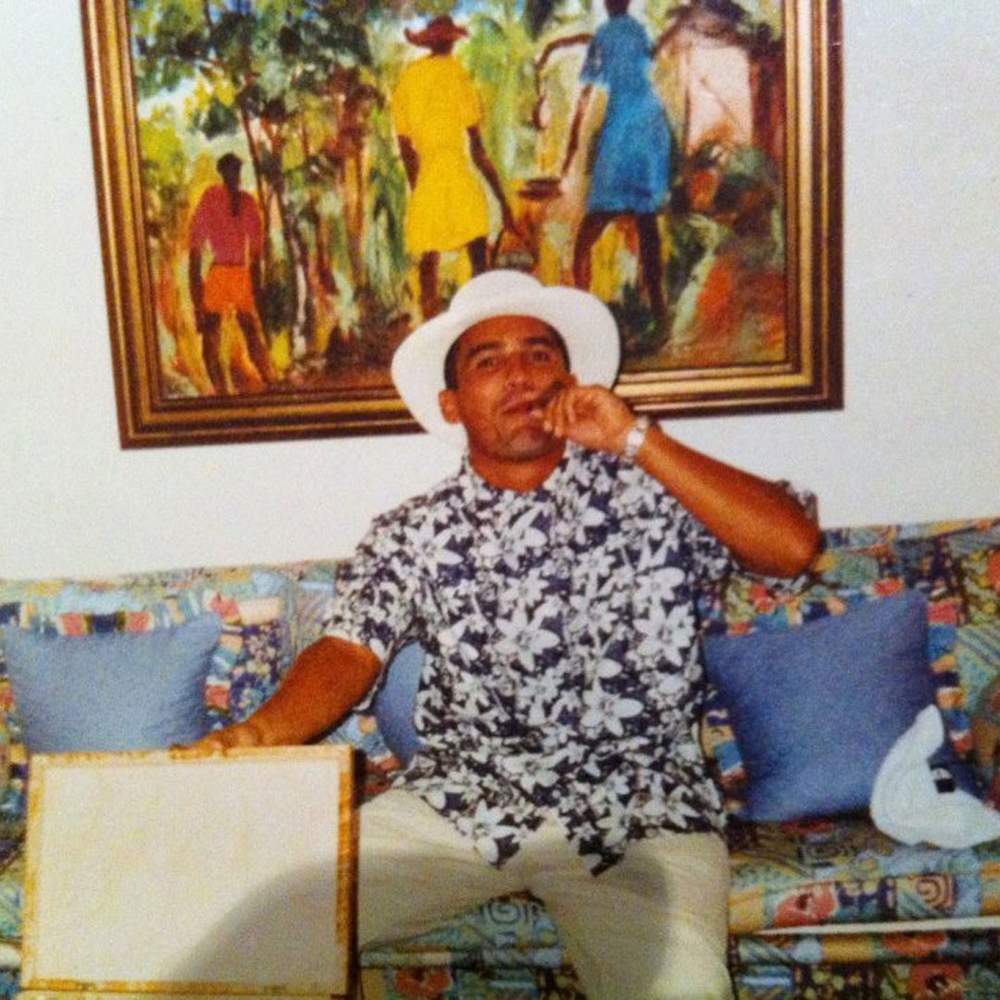

Lee spent summers working in Spanish resorts. He started by handing out flyers for nightclubs but graduated to working as a DJ. “People just wanted to dance their tits off all night,” says Alan, who accompanied Lee on one trip and was later to become a DJ at the Havana. “They were just lost in the music.” It was in places like Ibiza and Tenerife that many British clubbers first experimented with ecstasy – and later started taking it back to the UK. During his time in Spain, Lee mixed with DJs who were later to become some of the biggest names in the British club scene.

In Middlesbrough, a local club owner put him in charge of entertainment at the Havana and later the Arena nightclub in the town. The 1990s proved to be boom times. The money was rolling in. But it all came to a shocking end for Lee in 2001.

It’s been described as one of Middlesbrough’s most notorious murders. A 41-year-old market trader, Kalvant Singh, was found dead after falling from the window of a house in the town. But it soon became clear that it was no accident and he had been pushed out of the window.

A local news website said that Mr Singh had “found himself in the middle of a so-called turf war concerning the supply, distribution and sale of drugs to prostitutes in Teesside and Middlesbrough”.

Kalvant Singh

Four men were wanted in connection with the murder. One of them was Lee. He went on the run to Scotland, South Africa, Amsterdam, and finally to Jamaica. His family used to take holidays on the island and had friends there. After a year, Lee was arrested and extradited back to the UK. In 2004, he received a nine-year jail sentence after pleading guilty to manslaughter, grievous bodily harm and wounding. His father was also imprisoned for several years for trying to silence witnesses.

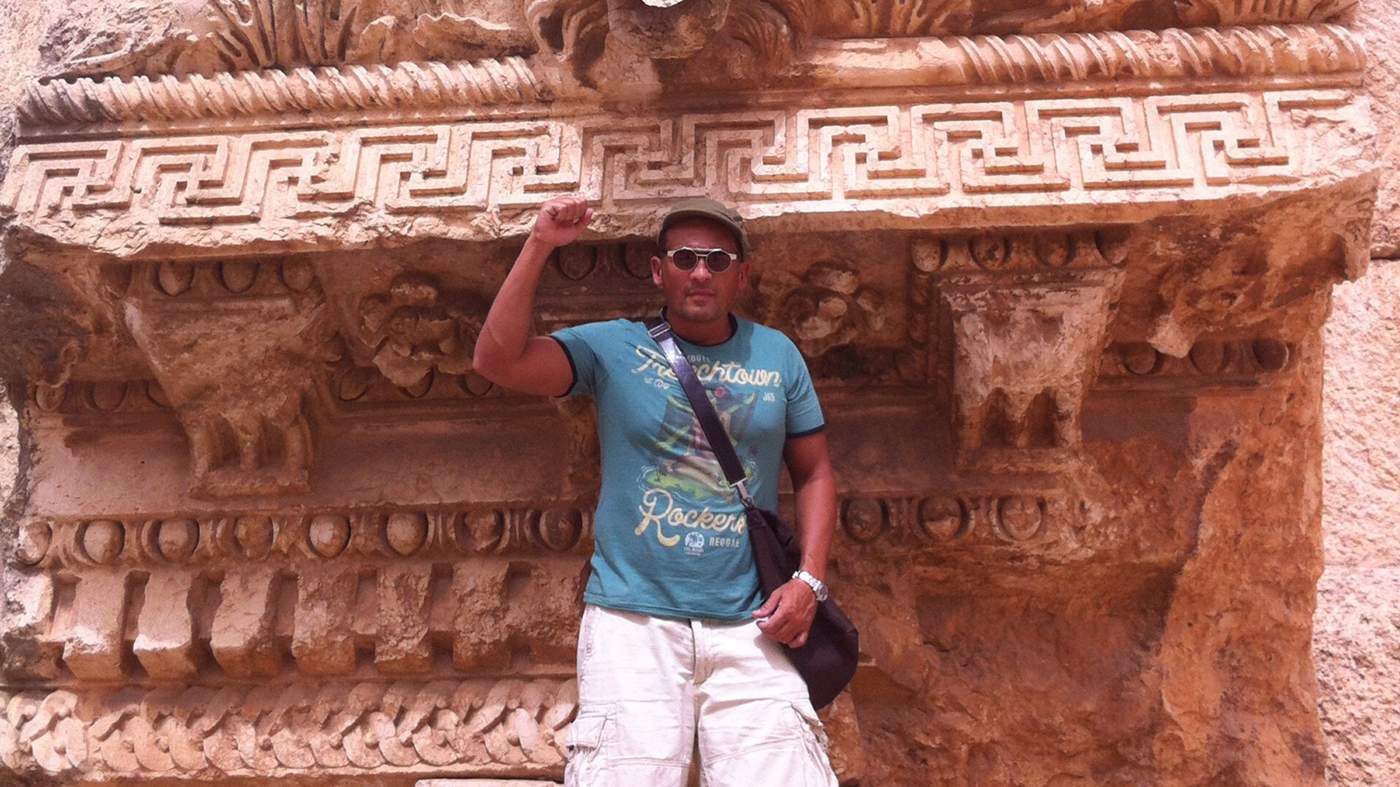

Lee was freed from jail in 2009 and settled in Portsmouth. He was married to Tamara, whom he had met while on the run in Jamaica. He told friends that he was going to turn over a new leaf. He wanted to go straight. He found work as an electrical cable fitter. But things didn’t work out as he planned. In 2015, Lee’s marriage was falling apart. A few days before Christmas, he boarded a flight to Lebanon. He said he was going to spend the holiday with a Lebanese friend in the Bekaa Valley. It was a journey that ultimately cost him his life.

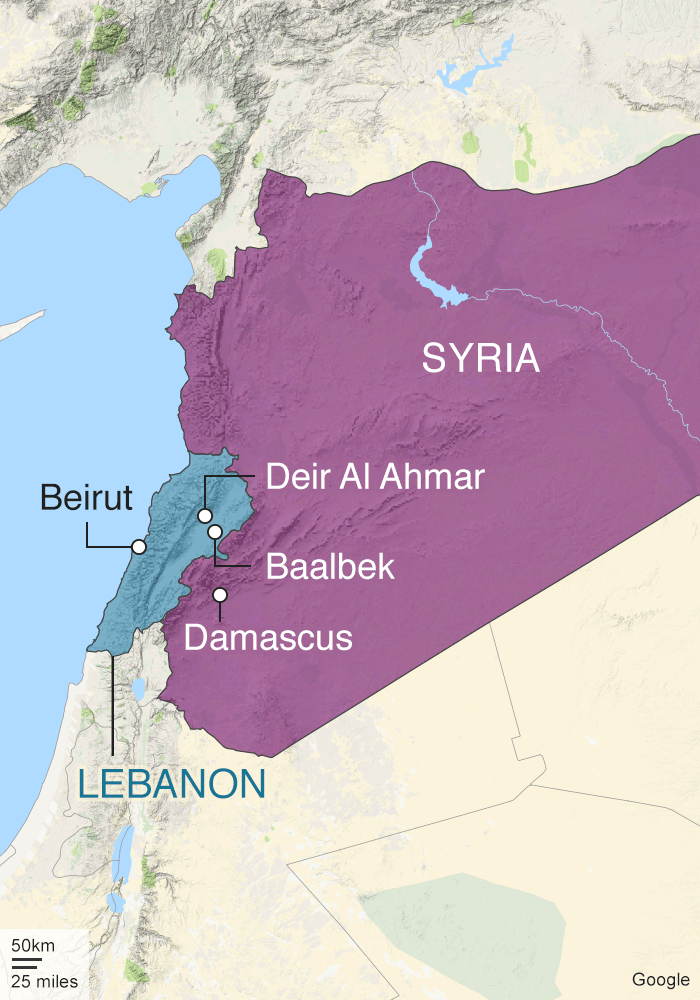

Some 2,300 miles (3,700km) from Middlesbrough lies Lebanon’s magnificent Bekaa Valley. Running for 75 miles (121km), it’s flanked by snow-capped mountains on one side and war-torn Syria in the east. The Bekaa has long been known as the country’s breadbasket, famed for its Roman ruins and world-class wineries. But it’s also a wild frontier, a place where the police often fear to tread – there are thousands of outstanding arrest warrants. The Lebanese call them the Farreen - the fugitives. If you know the right people in the Bekaa you can get away with almost anything.

Crime flourishes in this impoverished region. Smuggling over treacherous mountain paths is a rite of passage for many. One of the valley’s towns is infamous for being a hub for stolen cars. But it’s what you find at the feet of Mount Lebanon’s slopes that brings us here – hectares and hectares of lush, green, cannabis plants, producing some of the finest resin in the world.

Lee came to the Bekaa to stay at the home of a man called Adonis Al Masri, an inquest held in the UK after Lee’s death heard.

Adonis has a brown, gingery beard. But if you looked closely you’d see it was covering scars. As a teenager in the 1980s, he was caught up in one of the bloody feuds that frequently erupt among the Bekaa’s sprawling families, which control the valley. Adonis was shot in the face. He’s had dozens of skin-graft operations to try to repair the damage done to his jaw. A relative says that the traumatic event warped his life – ever since he’s relied on drink and drugs to numb the pain and combat depression. They say he’s a volatile character prone to mood swings.

Adonis and Lee knew each other from the UK. On one occasion, Adonis was introduced by Lee to his father - at a birthday party held at an Italian restaurant in London’s West End. Tom’s first impression was that Adonis “seemed all right”. It was a view shared by others. But during the UK inquest, Lee’s half-brother, Gerald Copeman, was quoted as saying that Adonis claimed to have killed the man who had shot him in his face. Several friends also recall Adonis bragging of ties to Hezbollah, the Lebanese Shia organisation whose military wing is designated a terrorist organisation by the UK. Perhaps, most bizarrely of all, he boasted of having helped free the British hostage, Terry Waite, who was held in Lebanon during the civil war in the 1980s. One of Adonis’s relatives described this claim as complete fantasy.

Whatever the truth, Adonis is from one of the most prominent and powerful families in the Bekaa Valley. His great grandfather, Mulhim Qasim Al Masri, was hailed as a courageous freedom fighter against Lebanon’s former Ottoman and French occupiers. Adonis’s grandfather, Nayef Al Masri, was a member of the Lebanese parliament from 1960 to 1972. Remember that name – we’ll be returning to him later.

Adonis, himself, has political ties. He organised gatherings at his home for one of the main Lebanese political parties during the recent election. He posted pictures of himself on social media with top politicians. Anybody seeing those pictures would be left with the impression that Adonis is a man with powerful friends.

Like almost everyone else in the Bekaa, Adonis had access to guns. It’s a way of life up in the valley. During the UK inquest, Lee’s half-brother Andrew Harrison recalled a FaceTime call during which Lee showed him around what appeared to be the Al Masri family armoury. There were sub-machine guns and rocket launchers, according to Andrew. But as Lee walked out on to a balcony, Andrew was to get an even bigger surprise from what he saw earlier on the video call. “On the right-hand side there was a pile – I would estimate to be about five high and six feet wide – of brown-coloured powder that I recognised to be cannabis,” he was quoted as saying at the inquest.

The court would hear that Lee was not in the Bekaa to celebrate Christmas after all. According to his family, he was in fact in Lebanon to do a drug deal. Four months later it would all go tragically wrong.

Of all the illicit activity for which the Bekaa is renowned, nothing surpasses its drug production. The UN ranks Lebanon as the world’s third-largest producer of hashish - a psychoactive substance smoked or ingested, made from cannabis resin - after Morocco and Afghanistan. Lebanon is also a significant producer of fenethylline - an amphetamine-like pill better known as captagon - and a transit hub for cocaine and heroin.

It’s hashish above all that’s made Lebanon’s name in the international drug world. In July 2018, the consulting firm McKinsey proposed legalising its cultivation and sale for medicinal use in order to invigorate Lebanon’s stagnant economy. The economy minister said it would amount to a billion-dollar industry, praising the quality of local produce as “one of the best in the world”.

In the freewheeling late 60s, at the time of Woodstock, the Summer of Love, and radical counterculture, Lebanese hash was in vogue. “Pilgrims” would travel the “hippie trail” by minibus from Europe to Lebanon seeking enlightenment at the source, before journeying on to Afghanistan, India, and beyond. The Brotherhood of Eternal Love - a zany Californian group of surfers, stoners, and drug dealers dubbed the Hippie Mafia - was said by the US Drug Enforcement Administration to have imported almost two tonnes (or more than 4,000 lbs) of Lebanese hash to the US by the early 70s.

Christina von Opel

Other notable buyers included the car heiress Christina von Opel, arrested in St Tropez in 1977 with 1.6 tonnes of Lebanese hash, and the former Welsh smuggler and spy turned author Howard Marks, who arranged the transportation of hundreds of kilos of the drug using Lebanese diplomats, according to Jonathan Marshall in his book The Lebanese Connection: Corruption, Civil War, and the International Drug Traffic.

Howard Marks

The Lebanese civil war (1975-90) was a great boon to the industry, with the collapse of state authority and rise of rapacious militias with few scruples about making money by any means. The area of farmland used for hash cultivation grew to four times its pre-war size; estimated at 10,000 hectares (roughly 10,000 rugby pitches). Not just hash but heroin, too, began to be produced in large quantities, and the warlords who controlled the supply lines and seaports amassed vast fortunes.

After the war, the heroin was mostly stamped out, and the hash farmland much reduced, though far from eradicated. The Lebanese militant group, Hezbollah, a prominent force in the Bekaa, has been accused of involvement in the drugs trade in Lebanon and overseas. But the organisation has dismissed allegations that it’s involved in drug trafficking and money laundering.

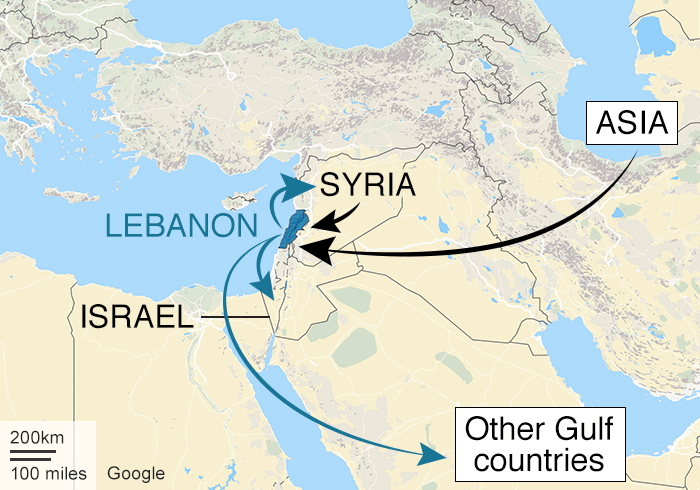

Recent years have seen the introduction of captagon, a stimulant reportedly consumed by fighters in the Syrian conflict, as well as recreational users in Gulf Arab states.

Captagon was originally the name of a pharmaceutical drug used to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and narcolepsy. But it was banned in most countries during the 1980s because of its addictive properties. Now captagon is reportedly the most popular drug consumed in the Gulf countries and Saudi Arabia. While these deeply conservative Islamic states take a strict zero-tolerance approach towards all intoxicants, users appear to be drawn to captagon in the belief they're taking “medication”.

A decade ago, captagon was produced in Bulgaria and other countries in south-east Europe, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. But in recent years, production appears to have shifted to Lebanon and Syria. Experts believe the illegal trade to be worth hundreds of million dollars a year.

In Lebanon itself, seizures of the drug have soared. In 2012, the authorities seized 79kg of captagon but by 2016 it had rocketed to 2,175kg.

Amphetamine and captagon trafficking flows 2014-2015

(Source: UNODC)

Throughout these decades, the illegality of the drug trade has been circumvented by official corruption, at times implicating figures in Lebanon’s highest offices. And members of the Al Masri clan have played their own part.

Remember Adonis’s grandfather, Nayef Al Masri, the Lebanese MP? Well, in 1970, a plane was seized in Crete carrying more than half a tonne of hashish worth more than $1m at the time. According to the book The Secret War Against Dope by Andrew Tully, the plane had taken off from a freshly-constructed airstrip on Nayef’s estate in the Bekaa.

It appears, then, that Adonis was no stranger to the world of drugs. A relative was quoted at Lee’s inquest as saying that the family owns a cannabis farm. As for Lee he was approaching 50 years old and felt he was running out of time to make his mark. He told Gerald that this deal was going to be the “big one”. In his own words, according to the inquest, it was “do or die”.

Lee’s plan for Lebanon was straightforward enough. He would fly out there in late 2015 to oversee a drug deal with the help of his host, Adonis Al Masri, the inquest heard. But upon reaching the Bekaa Valley, Lee’s plan began to quickly unravel.

The court heard details from friends and family about the strange things that began happening to him.

In January 2016, he said he was abducted at gunpoint and interrogated for several hours by people with American accents. He believed they were working for the CIA. The following month, while applying for a routine extension to his tourist visa, he claimed his passport was taken by the Lebanese authorities on the grounds that he was wanted by Interpol. British police later ascertained he was never, in fact, wanted by the organisation.

These bizarre developments, coupled with an imploding marriage back home, started taking their psychological toll. At the inquest, a friend who had been in regular contact with Lee, said that he “went downhill massively”. He lost weight, and would appear unkempt on video calls, at odds with his reputation for sharp dressing.

A family member was quoted at the inquest as saying that Lee had told him that he’d had “a smoke on a few occasions”, and that he had taken that to be a reference to cannabis. The coroner speculated that if this were the case, it could have further fuelled Lee’s mood swings. “We cannot know,” she said.

A member of the Al Masri family claimed that about a month before his death, Lee “had to be dragged down from a ladder after attempting to hang himself”, according to comments read out at the inquest. At other times, friends remember him rambling incoherently about being held by Isis and the Taliban. “He didn't sound like the same Lee I knew,” said one.

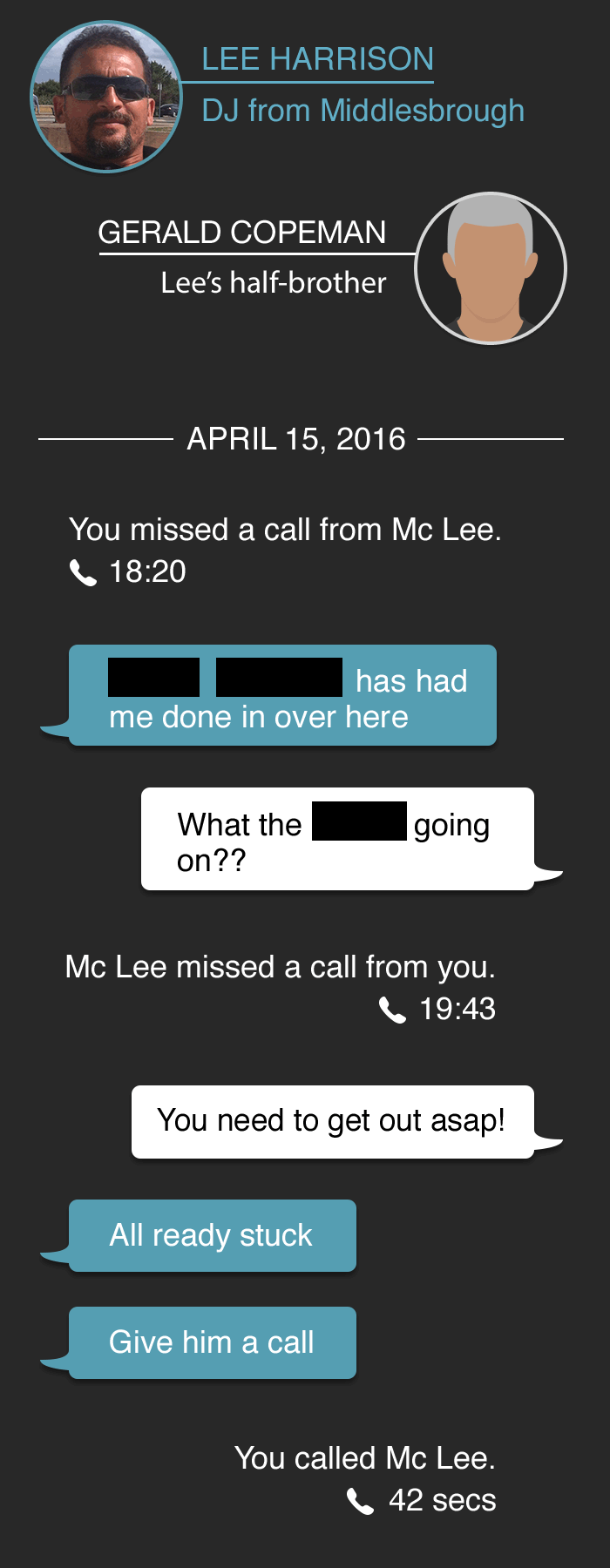

Towards the end, the court was told, Lee grew convinced his hosts had turned on him, thinking that he was an undercover agent. “They're all whispering and talking about taking me away and having something done,” Andrew recalls him saying. In his final days, things escalated dramatically. Lee told another half-brother by text message on 15 April that his host “has had me done in over here”. “You need to get out ASAP,” his brother replied.

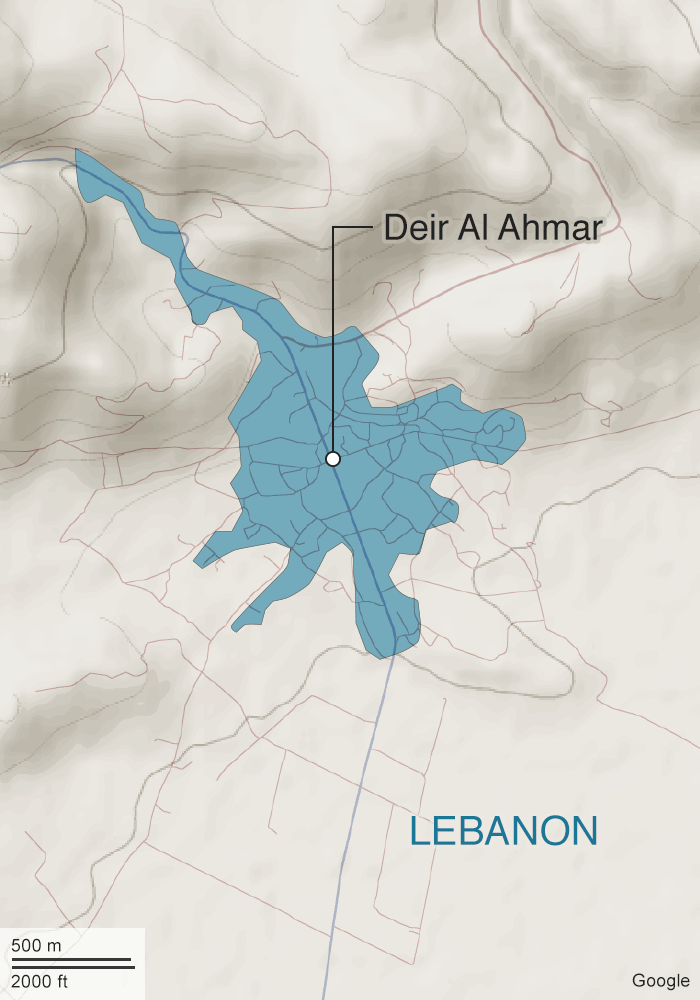

The next day, Lee fled the house, stabbing a gardener in the process, only to be knocked down seconds later by a car in the street. Lee told his family that he had briefly gone to hospital. The court heard that after that reported incident, Lee was moved to the home of Shehade Habshi in the nearby village of Deir Al Ahmar. Habshi describes himself as a friend of the Al Masri family.

Those back home who spoke to Lee at this time say he grew fixated with death, asking one friend to “look after his kids”, and telling his father Tom to have his body and blood checked in the event of his demise.

In contrast, Shehade Habshi told the BBC that Lee was “happy” in his household, eating healthily and bonding with his hosts over food, even teaching them how to make fish soup. On 20 April 2016, Shehade says he went out to buy some honey at Lee’s request. When he came back, he found Lee hanging from his front door. The Lebanese authorities later declared it a suicide, though Lee’s father and half-brother, Gerald, insist to this day that he was murdered.

Hundreds of mourners gathered at St John’s church in the heart of Middlesbrough to give Lee Harrison his final send-off on 20 May 2016. Pallbearers carried his coffin into the church to the sound of Natural Mystic by Bob Marley. The mourners heard about Lee’s devotion to his three children. Delivering the eulogy, a friend said Lee lived an “action-packed 50 years”. He added: “He was streetwise and had a special bond with his dad wheeling and dealing – that was the family trade.”

Back in Lebanon, the authorities were investigating. A news report in the local Daily Star newspaper on the day Lee died said it was initially believed he had taken his own life.

But it quoted doctors as saying that they didn’t believe he had killed himself.

The BBC has seen the Lebanese police report into Lee’s death. The first medical examiner was inconclusive – he could not determine whether Lee had taken his own life or had been murdered. He told the BBC that he “was not happy” about the process but would not comment further. Two other medical examiners later concluded that Lee killed himself. A UK pathologist who examined Lee’s body agreed that it was likely he died from hanging.

Adonis Al Masri was questioned by Lebanese police and denied having any business ties with Lee. The BBC repeatedly contacted the Lebanese businessman - who has no criminal record - for comment, but he didn't respond to the requests.

In the UK, the inquest into Lee’s death returned an open verdict in December 2017. The coroner said: “There is no evidence Lee was unlawfully killed, but I can’t be certain he intended to take his own life.” She also said that it was the opinion of the British police that it was highly likely that Lee was involved in some “organised criminality” while in Lebanon.

During the inquest, Gerald said in a statement: “Lee is a like a 10% man. He would introduce people to people, he told me this. I think Adonis did the introduction to the main supplier or cultivator, the main source.”

So why did things end so badly? Well, the inquest heard that a relative of Adonis Al Masri had told British police that Adonis had in fact stolen £150,000 from Lee, causing the drug deal to collapse. The inquest also heard that Gerald believed that Lee was the “surety, the living surety, and because it never happened, they made an example of him”.

The reality is we will probably never know exactly what happened in these final days. But Lee’s father is in little doubt. “I know my son and there’s no way he would take his own life,” says Tom. “He had too much to live for. He loved his children.”

We still do not know for sure whether the drugs deal was for cannabis or captagon, or indeed something else. But in one of our last telephone calls, Tom told the BBC he believed the drug deal was for MDMA, or ecstasy.

Lebanon is not known for producing that specific drug – although seizures of ecstasy are on the increase in the country. The shadowy world of illicit drugs is constantly evolving and throwing up surprises.

Lee Harrison had travelled a long way from those early, euphoric nights at the Havana club. But in the end, it may have been ecstasy that killed Hooligan X.