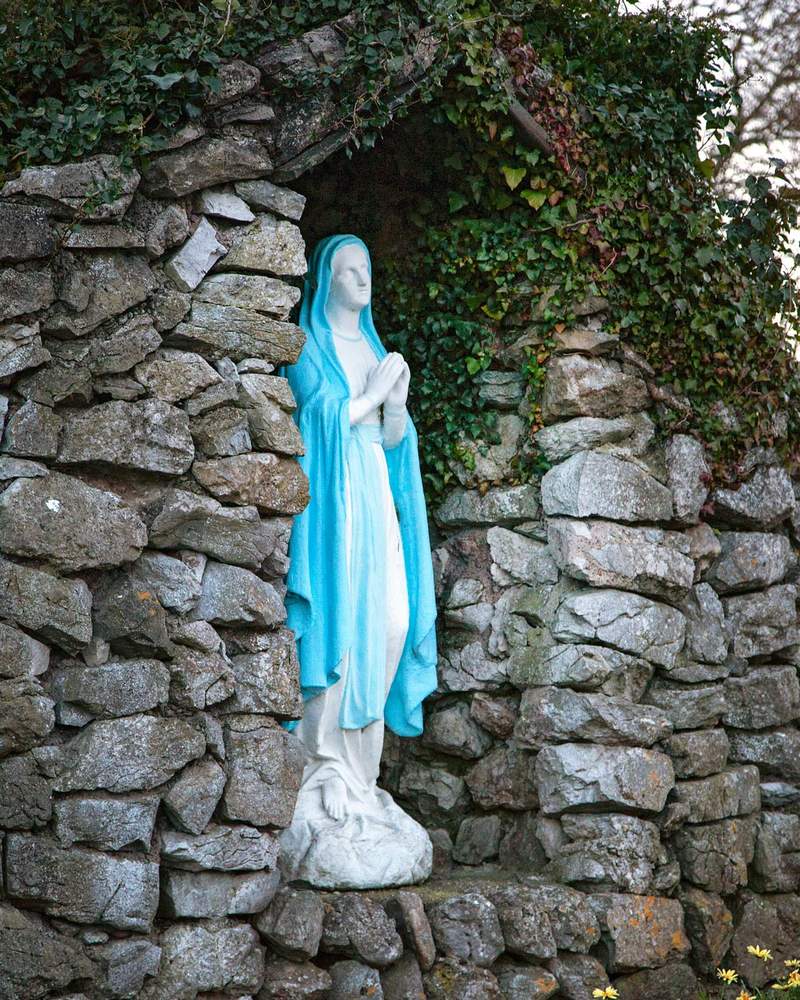

The walls were high and the wrought-iron gates opened on to a long, winding avenue.

At the end was a once-grand three-storey Georgian mansion in one of the better-off, sleepy suburbs of Cork city.

It was 1960, and Bridget arrived with a single suitcase and a rose-pink coat with a belt. She felt immediately uneasy.

“Everything was hidden from the outside, surrounded by shrubbery and trees. People couldn't see in.”

Once through the door, her clothes, her savings book, her small stud earrings and her bracelet were taken from her. She was given a uniform - clogs and a starched denim dress.

Bridget - like the other arrivals - was told not to speak about her life outside. All of them were given a different name. Hers was Alma - but she couldn’t get used to it.

None of the girls had committed any crime. But they had two things in common.

They were all unmarried and they were all pregnant.

At Bessborough, the long rooms of the girls’ quarters were on the top floor, looking out towards the cemetery.

The nuns called them all “girls”, but in truth the residents were anything from 13 to 30.

Bridget was 17 when she arrived. She was there because she had sinned, or so the nuns told her, by falling pregnant.

This was a mother and baby home, not a prison. Legally, Bridget and the other girls could have left at any time.

But in practice it wasn’t as simple as that. Any girl who ran away might find themselves rounded up by the police. And in any case, for the vast majority there was just nowhere else for them to go.

Each girl admitted to the home knew they would give birth there and stay until their baby was adopted - as long as three years.

They weren’t allowed outside except for short walks around the grounds and they had to be accompanied.

They were all given jobs. Some worked in the kitchens or in the red-bricked laundry building.

Bridget worked nights in a small room off the labour ward. Even in the quieter times, there was little chance to rest.

“We had to scrub the passageway… a massive wide passage with multi-coloured tiles on it.”

Occasionally she fed babies in a nursery lined with rows of cots. Another nursery held toddlers up until the age of three.

Bridget and the other girls were only allowed to spend about 30 minutes with each child. She doesn’t remember any toys.

“Some of the babies, they’d still hold their hands out. They didn’t want you to let go of them.”

Nuns and children at Bessborough

When a new girl arrived the others would quiz her about what was in the papers, desperate for some connection with life outside.

There were no calendars. All the days merged into one - an anxious wait for the birth and then for the inevitable separation from their children.

The girls signed release forms to allow for the adoptions but they were under overwhelming pressure to do so. They knew they couldn’t return to their families with their babies.

Joan, who worked in the kitchen, showed Bridget her toddler. He had a rash on his face and every day she prayed it wouldn’t heal in the hope that would stop him being adopted.

Another mother, Josie, showed off the intricate cardigans she was making for a small, dark-haired child. The little girl, who now goes by the name Mari Steed, went on to be adopted by a Catholic family in the US.

Mari Steed as a toddler (left)

June Goulding, a midwife who worked there in 1951, describes in her memoir the procedure for handing over the children.

Without warning, babies and toddlers would be washed and dressed up in new clothes and given to their mothers.

They would walk down a long passageway to a door that opened on to the nuns’ quarters where the children would be taken from their arms.

“The girls stood at the doorways watching this heartrending scene and the mother’s uncontrolled crying could be heard all along that long corridor,” wrote June Goulding.

“I witnessed the horrific ritual that would be repeated for each and every mother and baby in this hellhole.”

Escaping to England

Just a few months earlier, Bridget had been a teenager in love. They were dancehall sweethearts.

He was a man from Tipperary and 10 years older. At the weekends she would cycle five or six miles to the nearest dance to see him. “My first love. God, my first lesson in life. I thought he was lovely.”

Bridget was working as a cook in a big house for a racehorse-owning family outside Clonmel, the largest town in the county.

Most girls her age didn’t know the basic facts about sex and relationships. Contraception was illegal. Catholic leaflets encouraged girls to avoid kissing. It was a conservative time.

The Country Girls, Edna O’Brien’s novel about the love lives of two young women, had been banned by the Irish censor, publicly burned and dismissed as “filth”.

“I didn’t know anything about babies,” says Bridget. So when she began to feel unwell, and guessed that she might be pregnant, she had no idea what to do.

Abortion was out of the question. It was against the law and destined to remain so until 2019. But having a child out of wedlock was also a scandal.

“It was worse than murder in those days. It really was an appalling crime,” Bridget remembers.

For unmarried mothers, renting a flat or holding down a job wasn’t an option. There were no state allowances for women raising children alone.

And those children faced the stigma of being “illegitimate”, whispered about and judged by the community.

There was one way out.

Agencies like Miss Brophy’s International Bureau offered Irish girls live-in domestic jobs in the UK. All fares were paid. A girl could set off almost immediately.

To Bridget, it seemed like the perfect solution. She would be gone before anyone figured out what was wrong.

Within a few weeks she had a job with a family in Golders Green in north London.

She hadn’t told her boyfriend yet, but she felt sure he would follow her to England. In the event, she never heard from him again.

Bridget barely remembers what life was like with the family. But she felt anxious all the time.

She had escaped Ireland but she hadn’t escaped her feelings of shame and guilt. She needed to speak to someone, she couldn’t keep this secret bottled up.

“I was desperate, absolutely desperate,” she says.

Bridget went to confession at a Catholic church and left feeling relieved.

The priest had told there was a way she could get help. There were people she could talk to, who would understand her predicament. He gave her an address.

Piccadilly Circus, London, circa 1960

Young pregnant women like Bridget had been escaping to London and other big English cities for years.

There was still stigma in England around “illegitimate” children - and there were mother and baby homes, albeit with less punitive regimes. But Irish women could enjoy a level of anonymity in England that would have been impossible back home.

But there was always disquiet.

In 1936, the journalist Gertrude Gaffney wrote about the “dance hall evil”. “All concerned feel it unfair that they in England should be saddled with the expense and worry of them,” she wrote in the Irish Independent.

By 1955, London County Council had so many Irish babies left in their care that a dedicated children’s officer was appointed to spend six months each year in Ireland to try to find homes for them.

Social workers were said to have used the acronym PFI (pregnant from Ireland).

But there were Catholic charities in England which had a solution. Bridget had been given the address of the Catholic Crusade of Rescue in west London.

A repatriation scheme for women and girls in her situation had been set up in the 1930s by the Irish government, according to Lindsey Earner Byrne, lecturer in modern history at University College Dublin.

One motive was to stop babies from being adopted by non-Catholic families.

Catholic charities in the UK went to great lengths to persuade, and sometimes even coerce, young women to return home.

With no money, no friends and no support, Bridget felt like she had no choice.

In 1960, 113 Irish women were sent back, according to an Irish charity that collated figures in its annual reports. Bridget was one of them.

She was told that a woman wearing a white armband would meet her on the boat, and men in a black car would meet her at the harbour when she arrived.

“I didn’t suspect anything, what eventually happened. Not at all.”

It was a sunny day in August and she was on her way to Bessborough.

William

There were punishments at Bessborough. Bridget was made to stand in the corner for hours while heavily pregnant.

Her baby came three weeks early. Her waters broke in the middle of the night and she was shivering with cold.

It was dark. Another girl guided her down to the labour ward.

There was no pain relief and no kind words. Bridget’s baby boy was born on the third day of labour. She was exhausted but loved him immediately.

“I still see him. His eyes were looking around. Very inquisitive, beautiful, perfect baby, blonde, blue eyes and he sort of had hair as if it was combed beautifully.”

Bridget knew she would not be able to keep her son.

She wanted to call him William, a less common name in Ireland at the time. She thought it would be easier for her to trace him later.

But the nuns said Gerard was a more appropriate Catholic name for would-be adoptive parents. In the end, Gerard William was what went on the birth certificate.

For the first couple of days he was feeding well. But on the third day he had difficulty swallowing and started to get sick. So did Bridget.

William’s health worsened and the other girls told her he had been put in the “dying room”.

Bridget’s own health deteriorated too. She says she didn’t receive any medication.

She begged the nuns to send for a doctor for William. They told her he had a congenital defect but Bridget has always believed this wasn’t the case.

“Things stay in your memory that you cannot forget. He was a fighter - a good strong healthy baby, if he had got the proper treatment.”

But she says it took a further 16 days for William to be sent to hospital. He died less than three weeks after that.

Bridget didn’t get to see him. She says she wasn’t told where he was buried or anything more about what had happened.

She left the home just a week after William’s death. With no baby to give up for adoption, the home would no longer receive state funding for her.

Bridget remembers being very weak, and hampered by an abscess in her leg where she had been injected. But she knew she would have to find work quickly.

“There was nobody you could talk to about this, absolutely nobody. You had to keep working.”

Bridget didn’t want to admit to her family, who still thought she was in London, what had happened.

She decided to return to London and quickly found another job.

Emigrating, she says, was a lifeline after all she had been through. She went to the library and read all the books that were banned in Ireland.

Bridget married and had three daughters, and got on with a new life.

The scandals

Bridget’s story is not an isolated tragedy. Her experience was repeated at at least 17 other homes, affecting thousands of women across the country.

In recent years Ireland has confronted the separate scandal of the Magdalene Laundries, institutions where women and girls were confined and used as forced labour.

Now the spotlight has moved on to the mother and baby homes.

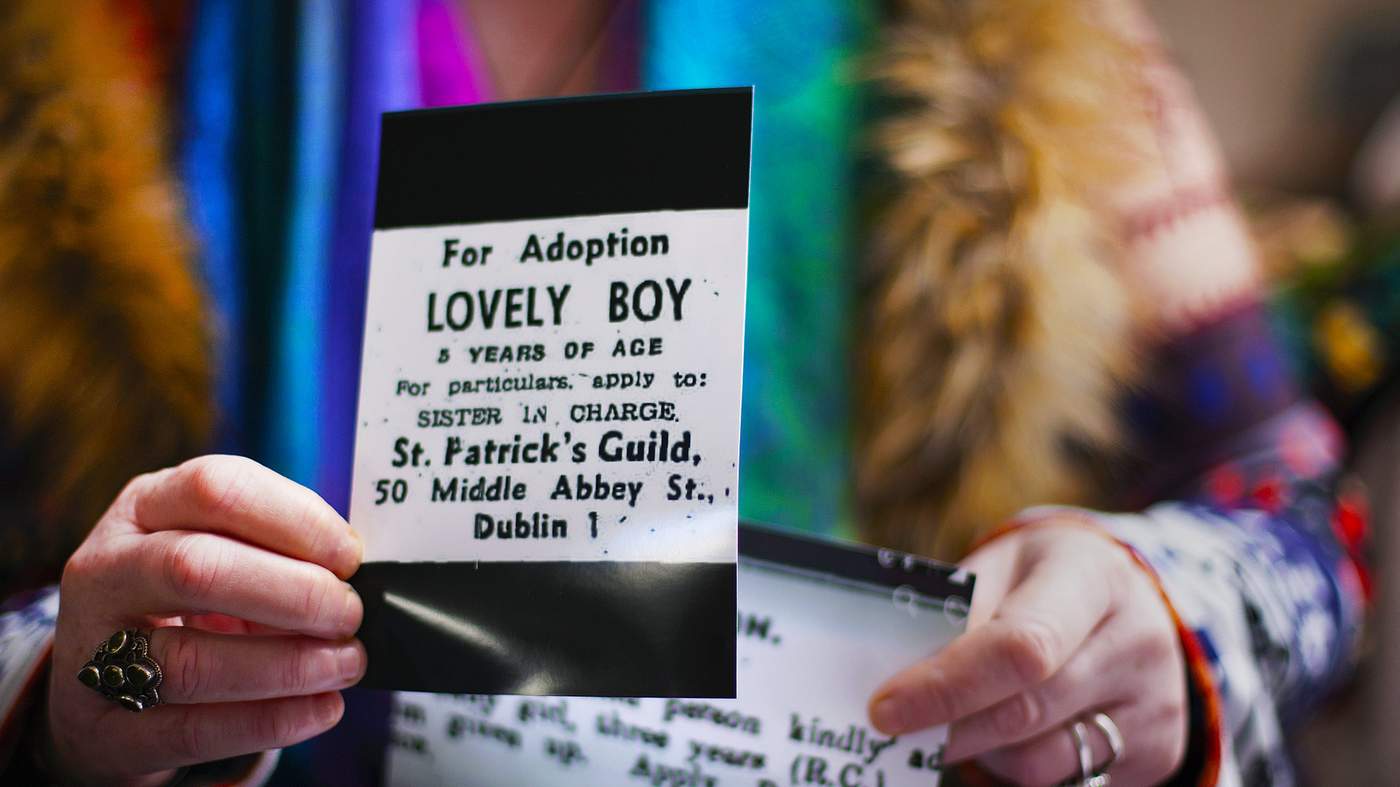

Over the past two decades Irish investigative journalists have uncovered a string of allegations against the homes, and irregularities surrounding the adoption of thousands of Irish children to America in the 50s and 60s. The film Philomena, starring Judi Dench, intensified attention.

In 2014, a local historian went public with her theory that almost 800 babies could be buried in a septic tank at a former mother and baby home in Tuam in Galway.

The international outcry that followed forced the government to act, announcing a full-scale investigation into 18 homes across the country.

The accusations against the homes include:

• Burying babies in unmarked and unrecorded graves

• Coercing women and girls to remain

• Poor medical care

• High mortality rates for babies

• Overwhelming pressure on mothers to allow babies to be adopted

• Emotional and physical abuse

• Illicit adoption; that babies were effectively “sold” to families in the US and elsewhere without proper procedures or consent

• Allowing medical trials without informed consent

• Use of dead babies in anatomical research

• Falsification of records

So why did Ireland end up with a system of mother and baby homes?

After independence from the UK in the 1920s, the new state had to decide how to deal with people needing government assistance.

The new government was also worried about sexual morality and unmarried mothers, says Lindsey Earner Byrne.

The Catholic Church had an important role in providing social services for the cash-strapped Irish state.

Officials called on religious orders to set up special homes to deal with unmarried mothers. These mother and baby homes received public funds and were inspected by the state.

Bessborough was one of the first.

The house and its grounds were taken over by the Sisters of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary in 1922.

Nuns at Bessborough

By the 1930s the order was running two other homes.

Questions were occasionally asked about the regimes in these places. Bessborough was even shut down for a short period in the late 1940s by Ireland’s chief medical officer, after an investigation revealed that 100 babies out of 180 had died in a single year.

There were never legal powers to detain women in the homes, according to Earner Byrne. But official documents made the girls sound like criminals.

“First offenders” describes those pregnant outside marriage for the first time, often judged less harshly than “repeat offenders”, deemed to be “hardened sinners”.

In 1930, the matron in charge of Bessborough said that “a number of the girls are weak willed and have to be maintained in the Home for a long period to safeguard them against a second lapse”.

Many had been referred to the homes by priests or doctors, with the consent of their families, who banished them to institutions rather than risk the stigma of supporting them. Some entered of their own free will as they felt they had nowhere else to go.

It is estimated that somewhere between 7,000-10,000 mothers gave birth in Bessborough, according to journalist Conall Ó Fátharta who has followed the scandal closely.

Rights groups say that up to 90,000 unmarried women and girls had their babies forcibly taken from them since independence. The true figure will probably never be known.

Tuam, the most notorious of the homes, closed in 1961. Bessborough remained open until the late 1990s.

Decades on

Carmel is Bridget’s eldest daughter. After growing up in London, she ended up marrying an Irishman and moving to Cork in the early 1990s.

Their bungalow sits on a hilltop. As well as raising their own children, the couple have also fostered.

Standing on the crest of the hill, Carmel could look down on the lough and a well-kept 60-acre estate of an 18th Century mansion.

“I could have moved anywhere around the city in Cork… but I literally circle Bessborough about five, six times a day.”

She heard rumours about this place. But she could never have imagined she was looking down at a place of immense significance for her.

Growing up, Carmel remembers her mother’s life as a flurry of activity - meetings and visits and social events. But she always had a sense that there was something in the background, something bothering her.

One morning in 1996, Bridget was visiting and, after being out all day, broke down in the kitchen. Carmel had never witnessed grief like it.

“She couldn’t speak to me, she couldn’t actually get the words out of her mouth to tell me.”

Carmel heard a secret family history. She had a brother who she never knew existed. But that brother was dead.

Thirty-five years on, her mother was still struggling to find the courage to try to uncover the truth.

“It was heartbreaking. She was helpless, she didn’t know what to do next.”

That day, Bridget had gone back to Bessborough but she couldn’t face knocking on the door. A couple of days later, she tried again, knocked on the door and asked the questions she’d always wanted to ask.

The sister, a short, stocky woman with cropped grey hair, took her into a small room lined with folders full of files. Eventually she found Bridget’s.

Then she led her down the avenue, on to a small path, towards a walled off area beside an old stone tower.

This was the Angels’ Plot - an area no more than 500 square feet. Small, plain metal crosses marked the graves of about two dozen nuns.

The sister tapped her foot on a small, unmarked patch of grass, about three-quarters of the way down on the right-hand side.

“Your baby is buried there,” she said confidently.

The nun told Bridget she wouldn’t be allowed to put a marker there to remember William.

Decades after Bridget left Bessborough, the home was still taking in young women.

Deirdre Wadding always thought her family loved her unconditionally. But when she became pregnant as an 18-year-old university student in 1981, she couldn’t believe their reaction.

Her mother, who had always been caring and approving, suddenly became cold and distant, a stranger to her.

“That trauma has never quite left me. I was filled with shame and guilt.”

Deirdre Wadding

Her parents shipped Deirdre off to Bessborough. Arrangements were made so she could continue her teacher training studies while in the home.

Conditions had improved by the 1980s. The food was OK and there was better antenatal care. In the evenings the girls would watch TV in the dayroom. There was no uniform.

Deirdre says the girls could leave the grounds with permission - they could go for a walk to the local shop in the village if they liked. Some had private rooms.

But Bessborough still felt like its own little universe, a house of secrets cut off from the world outside.

Deirdre’s new name was Ciara. A cover story was concocted about her having been sent to hospital for tests. Letters were sent via forwarding addresses so no-one would find out where the residents really were.

For a while, Deirdre shared a room with a 13-year-old girl who sobbed herself to sleep at night.

Even in 1981 the social pressure exerted on girls like Deirdre was immense. It’s easy to understand why they would think there was no alternative but to stay there. Deirdre’s family made it clear she wouldn’t be able to stay in her family home.

She says she didn’t want to give her baby up for adoption, but didn’t feel like she had any choice.

“We believed we couldn’t leave there. If I had walked out that gate, there was nowhere I could have gone.

“That was the level of indoctrination, that was how society worked.”

When the cover story started to wear thin, Deirdre’s father rang the home to see if they could “speed things up”. Her baby was induced three weeks early. It was a difficult birth, a forceps delivery on a metal trolley.

When it was all over, she was delighted to see her son.

“He was utterly beautiful. I was just mesmerised, at the one time just besotted and in love and devastated and distraught.”

That was the last time she would see him for 19 years.

Unlike in Bridget’s time, women in the 1980s did not have to stay there until adoptive parents were found.

Deirdre’s parents collected her just three days after the birth. They left through the big oak doors as if nothing had happened. She was inconsolable.

“It was like my heart just broke open. I don’t think I’ve ever cried as much in my life since. It was just unbearable grief leaving my child behind.”

A girl she was friends with inside the home pressed a handwritten note into her hand before she left. She still has it. It read: “A brave soldier never looks back.”

Deirdre learned to shut away her emotions, dissociate from them.

She has been reunited with her son but the contact is sporadic. It’s a loving relationship, but a complicated one.

“I can never have him back. Adoption is a life sentence. It doesn’t stop. You are blood but you are not that person.”

Catherine Coffey O’Brien spent most of her early life in and out of children’s homes.

In 1989, a few months after she left care, she passed through Bessborough’s doors.

Catherine was from a traveller background. Her dad was an alcoholic.

She didn’t fit in at the care homes. The way she spoke, the way she wore her hair, her earrings, it all seemed to be unacceptable.

Catherine Coffey O’Brien

“I fought internally every day of my life in those institutions to keep my identity.”

When she left at 16 there were gaps in her education and she felt abandoned. Sometimes she had to sleep rough.

When she found out she was pregnant her partner didn’t want to know.

After a chat with social services, she found herself on the train to Cork City, on her way to Bessborough.

Attitudes hadn’t changed towards girls like her.

“If you’d kept your legs closed you wouldn’t be in there. That was what was said.”

Catherine had jobs to do too. Cleaning, helping out in the kitchen and laundry, decorating the prayer room. To this day, she still hates the smell of beeswax polish.

The number of residents had shrunk by 1989, but still most women gave up their babies for adoption. It was expected that Catherine would do the same.

The thought terrified her. But if her baby wasn’t adopted, her child could end up in care.

“I wanted to do everything right by my child. I didn’t want him to have the same upbringing as me.”

One of the nuns trusted Catherine because she worked hard. She started sending her on errands in a taxi to Cork city.

A plan began to form in her head. One day, when she felt brave enough, she just wouldn’t return.

Another girl - Angela (not her real name) - persuaded Catherine to take her along. They made their escape.

Angela tried to go back to her parents’ house in Kerry but they couldn’t bear the scandal. They sent her back to Bessborough to have her son.

Catherine was luckier, taken in by her child’s paternal grandmother. She had her son two months later in hospital in Kerry.

In moments of dark humour she says she and Angela were the Thelma and Louise of Bessborough.

But Catherine’s escape didn’t start a revolution at the home. There was no mass exodus. Numbers just slowly dwindled until the doors closed for good in 1998.

Raising her son and three more children that followed was a battle for Catherine. She was strict with them.

“I was trying to break the cycle… so that my children would never know the inside of a dormitory.”

But her experiences of Bessborough left her with crippling doubts about her abilities as a mother.

“I was constantly on my toes... constantly trying to be the great mother.”

For a long time, she had nightmares that her children would be taken away. She couldn’t stop checking they were still in the cot.

Missing babies

The scandal over the treatment of women like Bridget, Deirdre and Catherine has been brewing in Ireland for over 20 years.

But the women say their experiences have never been officially recognised by the Irish state or by the Catholic Church. There have been strong words from politicians but there has never been a full state apology. No compensation has been paid.

While visiting Ireland, Pope Francis made a general apology for the Church’s treatment of mothers and babies and senior Irish churchmen have also made expressions of regret. But there has been no comprehensive apology and redress from the Church in Ireland.

All three women gave evidence to the state inquiry opened in 2015 - the Mother and Baby Homes Commission of Investigation.

On 17 April it reported back on just one aspect of the scandal - burial practices.

According to the commission, more than 900 children died at Bessborough - or at hospital having been transferred. But the burial places of only 64 are known.

The Congregation of the Sisters of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary - the order that ran Bessborough - said it did not know where the other 800 children who died at the home were buried. The commission said this was “difficult to comprehend”.

The Angels’ Plot at Bessborough - the place Bridget was shown - only has one child buried there, the commission says. It is not thought to be William.

The commission thinks it is likely that at least some of the children are buried in unmarked graves in the rest of the 60-acre Bessborough site, but does not consider it feasible to excavate the whole area.

At least 14 women also died at Bessborough. Their burial places are also unknown.

“I feel deeply for the families who may not get the answer they are seeking,” said Children's Minister Katherine Zappone. “In a lot of cases, the evidence is not there.”

William may be buried at Cork District Cemetery, but the commission has been unable to get records from that cemetery. A couple of years ago, Bridget placed a plaque for William at Bessborough, but her search goes on.

And the commission’s final report into Ireland’s system of mother and baby homes has been postponed until 2020, after a series of delays and extensions.

Until it concludes, there will be no apology and no practical help for any of the people who spent time in these homes.

Mothers and children who passed through Bessborough’s doors report difficulties and long delays obtaining documents when trying to trace their relatives or access health records to find out if they were part of vaccine trials carried out in the 1960s.

Mari Steed, one of the Bessborough children that Bridget remembers, was adopted at 18 months by a Catholic family in Philadelphia.

She eventually found her mother Josie in the UK and visited every year until her mother's death in 2013. When Mari was able to get her full file from Bessborough she found that she had been in a vaccine trial in the 1960s. Her mother Josie said she had not been consulted.

Mari believes there will be no accountability for what went on at the home.

Noelle Brown was adopted from Bessborough in 1967. She decided to trace her birth parents in 2002. Countless delays followed. Her mother had died in the 1990s.

A few months ago she got her full file from Bessborough. But it has been heavily redacted and much of the rest is barely legible.

She still can’t find out whether she was subject to the medical trials that were carried out there in the 1960s and 70s.

She says the commission told her it is prohibited from disclosing any information related to the trials.

Noelle Brown is now an actress

“You come up against this all the time. Another bloody letter from someone going, ‘Disappear, we’re not going to help you’.”

Under current Irish legislation, adopted people have no statutory right to their birth certificates or early life files.

Bridget has struggled - with the help of Carmel - to get her documents. But she can’t get more evidence on the medical treatment that preceded William's death.

A leaked memo from the Irish Health Service Executive (HSE) in 2012 stated that the infant mortality rate in Bessborough between 1935 and 1960 was about seven to eight times higher than the national rate at the time.

But until all the records are forensically analysed, the history of what really happened inside Bessborough will remain unknown.

With the state inquiry’s report taking so long to complete, women like Bridget, Deirdre and Catherine are losing hope of finding the truth.

Bridget blames the Church. “If they told the truth, even now if they came out with the truth it would be something. But they’re still denying what happened.”

The office of the Archbishop of Armagh, Catholic Primate of All Ireland, when contacted for this piece said it would not respond until the report was published.

The Congregation of the Sisters of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary refuses to discuss individual cases. “All records... were passed to Health Service Executive (HSE ) in 2011. We are co-operating fully with the Mother and Baby Homes Commission of Investigation.”

The last time a representative gave an interview was in June 2014 to the now-defunct TV3. Sister Sarto denied claims that adoptions were forced and said nuns were providing a service to women cast aside by society with no other option.

“We gave our lives to looking after the girls. And we’re certainly not appreciated for doing it.”

Deirdre thinks the system she went through was the fault of both Church and state, but also of a wider society where people looked the other way.

“We did nothing wrong and yet we suffered for it, we suffered loss, banishment, judgement, trauma, grief.”

Even when the inquiry’s report is published, the women worry that the legislation underpinning it suggests the full archive will be sealed.

Catherine Coffey O’Brien

The evidence gathered by the inquiry cannot be used in criminal or civil proceedings. Nor will former residents be guaranteed access to their own personal information. Catherine can’t understand why.

“It’s almost like they’re eradicating the past,” she says. “What more are they trying to hide?”

Bridget still has such vivid memories of walking through the heavy wooden doors of Bessborough House. It’s as if it happened only yesterday.

Now, she lives in a ground-floor flat in west London, and leaves the radio on all the time. Silence makes her dwell on things so much, she says.

The street where she lives is just a short distance from Westminster Cathedral, where she goes from time to time, to hear the choir. She can sit there for hours.

Sometimes she lights a candle for William. She has thought of him every day for 58 years.

“It was complete loneliness,” she says.

She has rarely spoken about the three suicide attempts and the spell in a psychiatric hospital when she returned to London in 1960.

She has never fully recovered from the trauma of William’s death and her experiences of Bessborough.

“I’ve come to the conclusion that I’ll be like this until I die, that I cannot get better. I’ll never be able to forgive them,” she says.

Over the past couple of years, she has sought support in a private Bessborough Facebook group. Speaking in a safe space brings some solace to her and others.

But the shame she felt for all those years still makes her reticent to speak out publicly. She’s spoken to the BBC under a pseudonym.

Bridget wants only one thing from the state inquiry - to know exactly where William is and to be buried with him.

When he was born she couldn’t do anything to help him. By telling his story, and her own, she wants to honour the memory of the little boy she lost.