It was still dark when the private jet began its descent. Inside, its decor was sumptuous, the black leather seats piped with red, but outside rain was falling and the temperature on the ground below was a bracing 2C. The date was 21 January 2013, and the island that the plane was heading towards hadn't yet woken up.

The candy-red Challenger 605 aircraft carried the registration G-LCDH - the initials of Lewis Carl Davidson Hamilton, the World Championship-winning Formula One driver.

The previous month, Hamilton had flown on the jet with his then-girlfriend, the former Pussycat Dolls singer turned X Factor judge Nicole Scherzinger, and their families, to Hawaii for a Christmas holiday. The aircraft’s latest destination wasn’t so celebrated as a hang-out of the rich and famous.

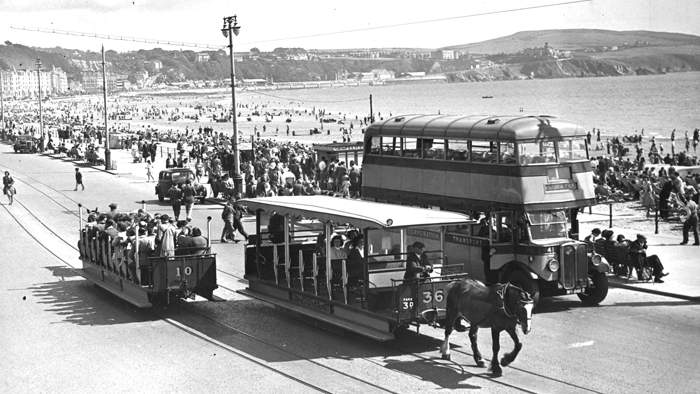

It wasn't Monaco or Miami Beach. It wasn’t Dubai. It wasn’t even the Channel Islands. It was the Isle of Man, the Crown Dependency between Ireland and Great Britain best known for its tail-less cats and its motorcycle race.

But the plane wasn’t going to stick around for long.

At 06:15 it landed. To one side of the runway were the waves of the Irish Sea. To the other was Ronaldsway Airport’s modest cream-and-blue Art Deco terminal building.

Despite the early hour, someone was waiting for the jet - an Isle of Man customs official. Hamilton’s advisers had paid a £60 fee for the privilege of getting the official there early to stamp a form that showed VAT had been paid in full.

In December 2012, Stealth Aviation Limited - a company of Hamilton’s in the British Virgin Islands - paid $26,817,260 for the jet.

Hamilton’s social media accounts show he used it for holidays and other personal jaunts, not only business. On Instagram, he posted several photographs - including one showing his bulldogs, Roscoe and Coco, on board. He was especially proud of its distinctive colour scheme.

“Every time I’m at the airport you see these really sad, old white planes, with the saddest stripe down the side,” he told US talk show host Jimmy Kimmell in 2015. “If I get a plane, I’m going to pimp it out.”

According to the Sunday Times Rich List, Hamilton has a £131m fortune. Normally, companies that use planes for business reasons are entitled to a VAT refund, but private individuals are not.

According to emails held by Appleby, the law firm at the centre of the Paradise Papers leak, Appleby formed a VAT-registered leasing business on the Isle of Man for Lewis Hamilton.

The new company, Stealth (IOM) Limited, leased the jet from Hamilton's British Virgin Islands company, Stealth Aviation Limited, and imported it into the Isle of Man. It was then leased again to a UK jet management company that provided Hamilton with a crew and other services - and which leased it back to Lewis Hamilton and his Guernsey company, BRV Limited.

Because of these “commercial” transactions, Hamilton’s advisers were able to arrange a 100% VAT refund when the plane landed at Ronaldsway. The £3.3m VAT bill was paid on Hamilton’s behalf by an Isle of Man accountancy firm. So when the aircraft landed, the customs official attending out of hours stamped a VAT-paid form to be kept on board the aircraft. This granted the aircraft “full and free circulation” in the EU.

Leasing documents in the Paradise Papers show that Hamilton’s company, BRV Limited, expected to use the plane two-thirds of the time, with him signed up personally to use the other third. EU and UK VAT rules state that refunds should not be granted in relation to private use of aircraft – but Hamilton got a full refund.

Hamilton wasn't alone in doing this. More than 50 others have imported planes to the Isle of Man with Appleby’s help. In total, the Isle of Man has refunded more than £790m to 231 aircraft leasing companies that have imported jets. And Paradise Papers documents suggest Lewis Hamilton is far from the only super-rich visitor to get a VAT refund on jets they used for pleasure as well as work.

Lawyers acting for Lewis Hamilton say the driver has a “set of professionals in place who run most aspects of his business operations and that no subterfuge or improper levels of secrecy had been put in place".

In a statement, they say Stealth (IOM) Limited was formed to run a leasing business and hire the aircraft on a long-term basis at a commercial rate. They add that the company made all necessary disclosures to Isle of Man officials, who approved the approach.

The lawyers said that reducing taxes was not the motive, but even if it had been, it is lawful to lease rather than buy in order to reduce VAT.

The Isle of Man has one of the largest private aircraft registries in the world, with about 970 luxury jets officially registered since it began in 2007. In light of the Paradise Papers revelations, the Isle of Man government has invited the UK Treasury to conduct an assessment of the practice of importing aircraft into the EU through the island. It has denied "mistakenly" refunding VAT and says it follows the same policies, rules and regulations regarding the treatment of VAT as the UK.

Once the form was stamped, Hamilton’s candy-red plane was free to take off again at 08:10. It had spent less than two hours at Ronaldsway, and didn’t even stay long enough to see the sunrise.

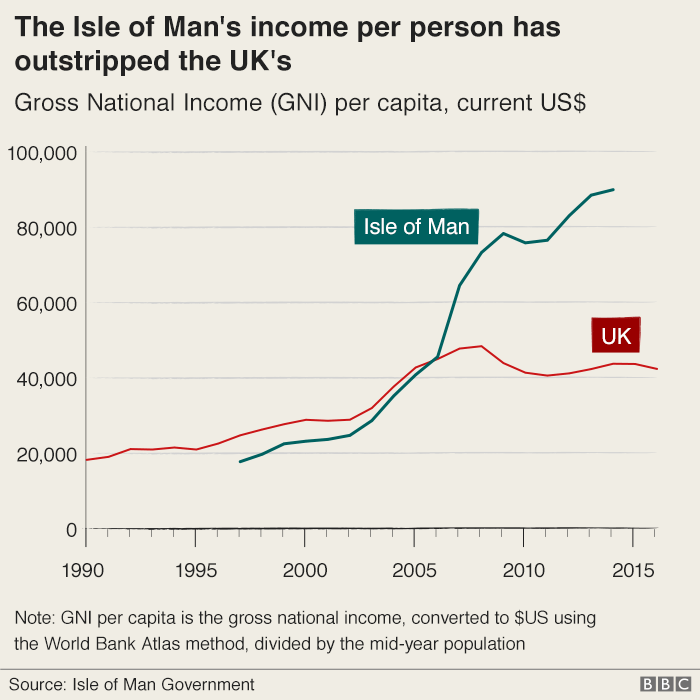

In 1961 the Tynwald, the island’s parliament, began cutting income taxes in order to attract incomers. In the 70s, there was an influx of merchant and commercial banks too.

By 1980, the top rate of income tax was set at 20%, where it is still today, and the maximum amount payable remains capped. Currently the corporation tax rate is 0%, compared with 19% in the UK. On the Isle of Man there is no capital gains tax, inheritance tax or stamp duty.

The effect of all this was an economic boom on the tiny island. Over the past 30 years, its economic growth has been three times that of the UK’s.

Some critics have argued that the island's economy has become too reliant on finance. The Manx government rejects this. "We have a fully diversified economy," says Howard Quayle, the chief minister. "Our e-business sector is just as big as our financial services." The government points to a burgeoning space industry, cheese, scallops and films – more than 100 movies and television series have been shot on Man since 1995.

While he studied commerce at Liverpool University and, later, trained as an accountant in London, Phil would regularly come home to visit his family and, each time, he noticed its remarkable transformation.

I was living off the island and I thought: ‘Good old Isle of Man, it’s doing really well, notching up these double-digit increases in growth.’”

He didn’t think too much about where that growth was coming from. That would come later, and it set Phil on a collision course with many of his fellow islanders.

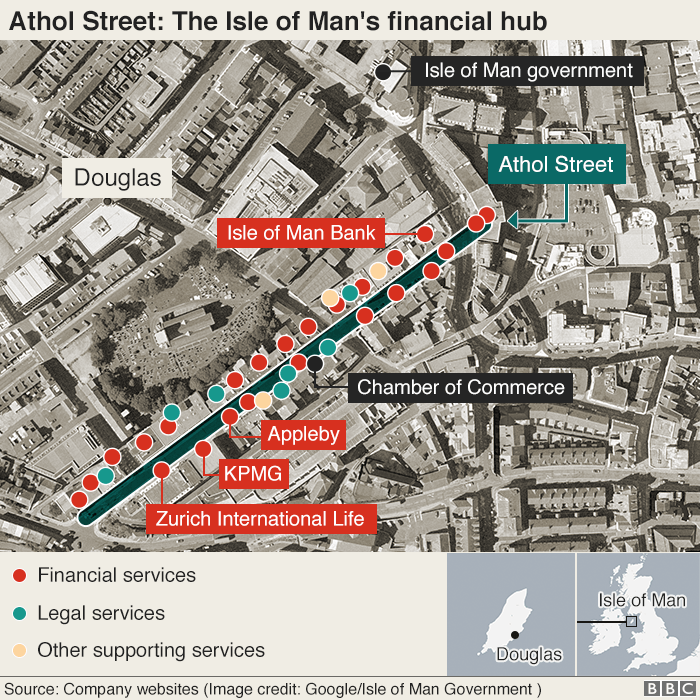

In the middle of Douglas, a short walk up the hill from the marina at Douglas Harbour, there’s a thoroughfare of anonymous-looking Georgian terraces called Athol Street.

The buildings all look smart, if unassuming. You could be in almost any British town. But if you look closely at the names of the firms operating here, you’ll realise this is no ordinary road.

Among the companies along here are KPMG, Zurich International Life and Appleby - the firm at the centre of the Paradise Papers, a huge leak of financial documents that sheds light on how the ultra-wealthy invest their cash.

This is the centre of the Isle of Man’s financial district. This island, with its population of less than 85,000, has more than 30,000 registered companies. Some 17% of the island’s income comes from banking, finance and business services and the same proportion comes from insurance.

Each lunchtime, office workers in pinstripe suits emerge from Athol Street’s buildings. Many huddle together in Coffee Exchange or the Courthouse bar around a laptop or a sheaf of papers, keeping their voices low as they talk business.

There’s the occasional visible indication that this is a place apart, like the sign in the window of The Thirsty Pigeon pub declaring that it accepts Bitcoin. Unlike some once-popular British seaside resorts, the town looks quietly prosperous. For the most part, the former boarding houses along the promenade in Douglas are clean and freshly painted.

But for all the money that passes through the island, you don’t see the kind of conspicuous wealth you’d expect in Monaco or even Jersey.

On Manx roads you’ll spot the occasional Rolls Royce or Ferrari, but a lot more Hondas and Fords. There are some good restaurants in Douglas, but none have a Michelin Star.

On Strand Street, the capital’s main shopping thoroughfare, if you look hard enough you can find Lacoste, Hugo Boss, Vivienne Westwood and other designer brands on the shelves. But there are many more branches of the shops you would find on any British High Street - TK Maxx, River Island, Boots and Dorothy Perkins.

In Ramsey, in the north of the island, there’s a “superyacht helicopter consultancy” with frosted-glass windows. Across the street is the Stanley pub, whose chalkboard promises games night on Wednesdays and karaoke at the weekend.

The political system has, however, been praised as good for industry. “Businesses say that government officials are accessible and regulations stable,” the Economist wrote in a 2015 profile of the island.

The government makes a virtue of this predictability, even boringness, when attracting investment. “We have had the same government for 600 years and there are no surprises,” Jonathan Mills, director of e-business at the Manx department of economic development, told the German broadcaster NDR.

“There is no issue around the court system, there is no issue around corruption.”

For Craine, the more significant factor that keeps the Manx economic model in place is apathy.

“There are many people working in the offshore industries who are working there as a clerk or indeed as a manager who need that monthly salary to pay the mortgage, to put bread and jam on the table at the end of the month for their family,” he says.

“I can’t criticise him or her for doing that but the system is geared so that we are as a society knowingly facilitating tax avoidance. And that’s what troubles me.”

Perched above Douglas’s promenade is an estate of grand Edwardian villas known as Little Switzerland. The name long predates the island’s finance boom, but today it feels more appropriate than ever.

Drive to the western coast of the island and, against the backdrop of the Irish Sea, you’ll see the occasional tholtan - the Manx word for an abandoned house, a reminder of the hardship and emigration that characterised so much of the island’s past.

Some on the island worry those days could return. Brexit has increased uncertainty, and since the 2008 crash, there has been ever greater scrutiny of offshore finance. In that year the UK’s then-Chancellor of the Exchequer Alistair Darling accused the island of being a “tax haven sitting in the Irish Sea”.

Karran, for one, says the Manx government hasn’t done enough to protect the island’s public services from the risk of future economic shocks. “Our next generation should be fiscally secure,” he says.

It’s not the banks he blames but the politicians, whom he accuses of “willful neglect”.

The government rejects warnings from critics who say the economy needs to diversify. The government also strongly rejects the “tax haven” label. “We're not, you know, a brass plaque in the middle of the Irish sea,” Howard Quayle, the island’s chief minister, told Panorama. “We take our international responsibilities exceedingly seriously.”

Quayle also points out that the OECD rates the island “compliant” in terms of transparency standards and that when in 2015 the EU published a list of tax havens, the Isle of Man was not on it. In 2013 the then Prime Minister David Cameron said it was no longer fair to describe any Crown Dependency as a tax haven.

The revelations in the Paradise Papers will focus international scrutiny on the way the Isle of Man does business. For now, those like Phil Craine who want to change dramatically the island’s attitude to finance remain in a minority. He accepts the changes he would like to see would hurt. “I don’t know what’s going to come next. But I do know I’m not happy with the current model.”

Craine is hopeful that, whatever happens, the Manx economy will end up, as ever, standing on one of its three legs. But no-one can know for sure which way it will land.