Many are standing in silence. Arguments break out as people try to push in. Some of those queuing are more than 80 years old.

They will be queuing for most of the day. Most don’t eat or drink for fear they will need the toilet. Not because there aren’t any toilets, but because they might lose their place in the queue.

This is one of the checkpoints at Ukraine’s front line. About 30,000 civilians cross the contact line every day.

“Don’t you see? People are dying here!” one of the women queuing says to me.

She doesn’t mean this figuratively.

Eighteen civilians, mostly elderly, have collapsed and died crossing the front line since December, the OSCE (Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe) reported in April. Most of the deaths were from heart-related complications.

Others in the queue fall ill or faint.

Some are crossing the front line to visit family.

But most are waiting to carry out a laborious, but necessary, errand - collecting their pension.

I decide to travel to the front line to find out more.

There are five checkpoints on the Russian-backed eastern territories - four in Donetsk region and one in Luhansk region, and five corresponding checkpoints on the Ukrainian-controlled side.

The queue moves slowly as permits are checked on either side of the front line. Between the checkpoints is a walk of up to 3km (1.9 miles) across the contact line. It is mined on both sides and a curfew on shelling during daylight hours is not always observed.

But statistics suggest another big and unexpected risk - the sheer exhaustion of queuing. Most of those crossing are elderly.

At Stanytsia Luhanska, the checkpoint in Luhansk, paramedic Natalia Sylkina is struggling to cope.

“It’s been madness today,” she says. She explains that she and her colleagues are bringing people out of the queues who have already fainted, or are on the verge of doing so.

“There’s already been around 30 patients, with six or seven of them fainting.”

The previous day they treated 31 patients, she says.

“They’re all squeezed together. They can’t breathe… We’ve been raising or lowering their blood pressure here or resuscitating them.”

I discover that those who are 80 and over can actually go straight to the front of the queue, but most don’t know about this, or don’t believe it when I tell them - so fearful are they of losing their place.

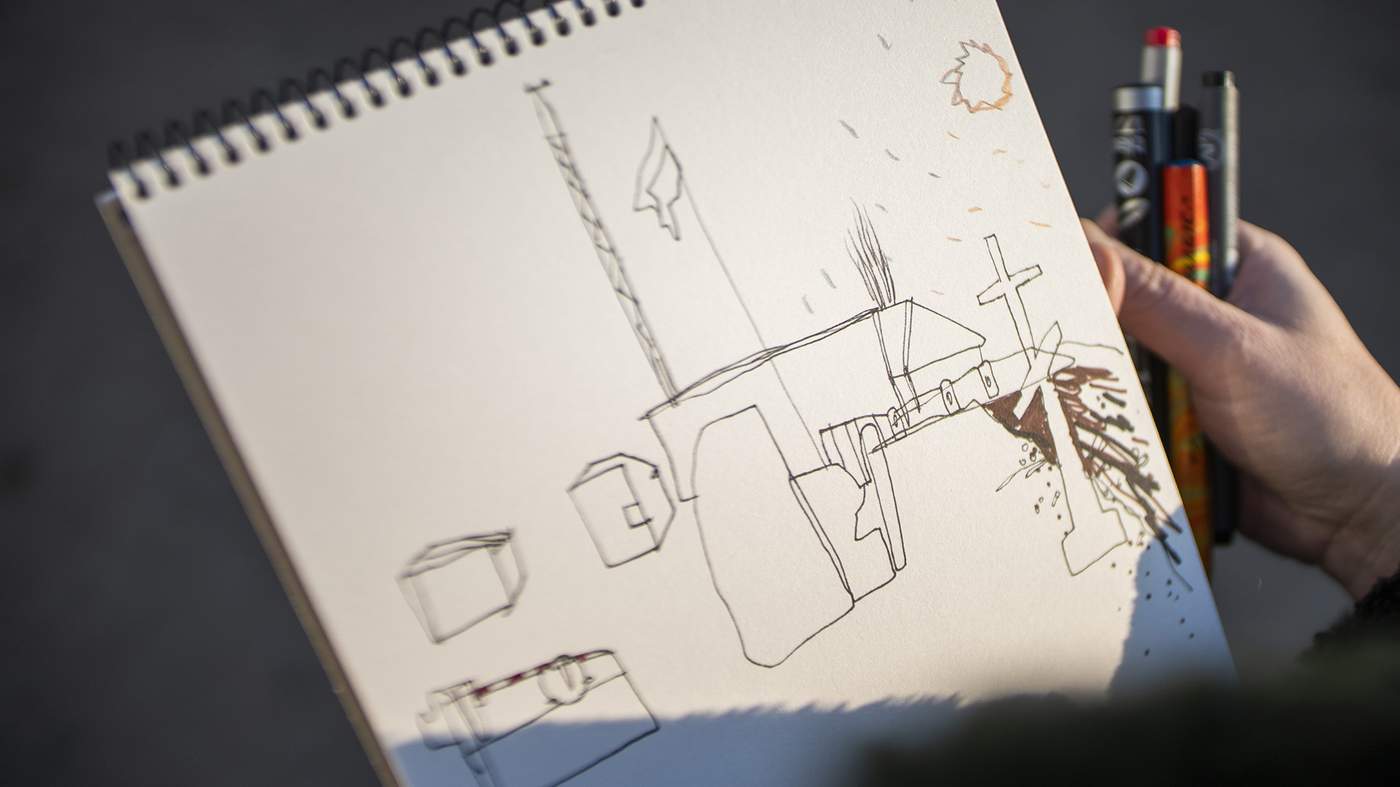

I also travel to another crossing point - Mayorsk. Despite the curfew on shelling I hear the sound of gunfire and the army tells me to take cover.

One of those queueing there is Karolina, nine months pregnant, and crossing to see family on the other side.

"It's difficult now. I'm scared that I might have to give birth on the way," she says.

But, as at Stanytsia Luhanska, most of those queuing in Mayorsk are elderly.

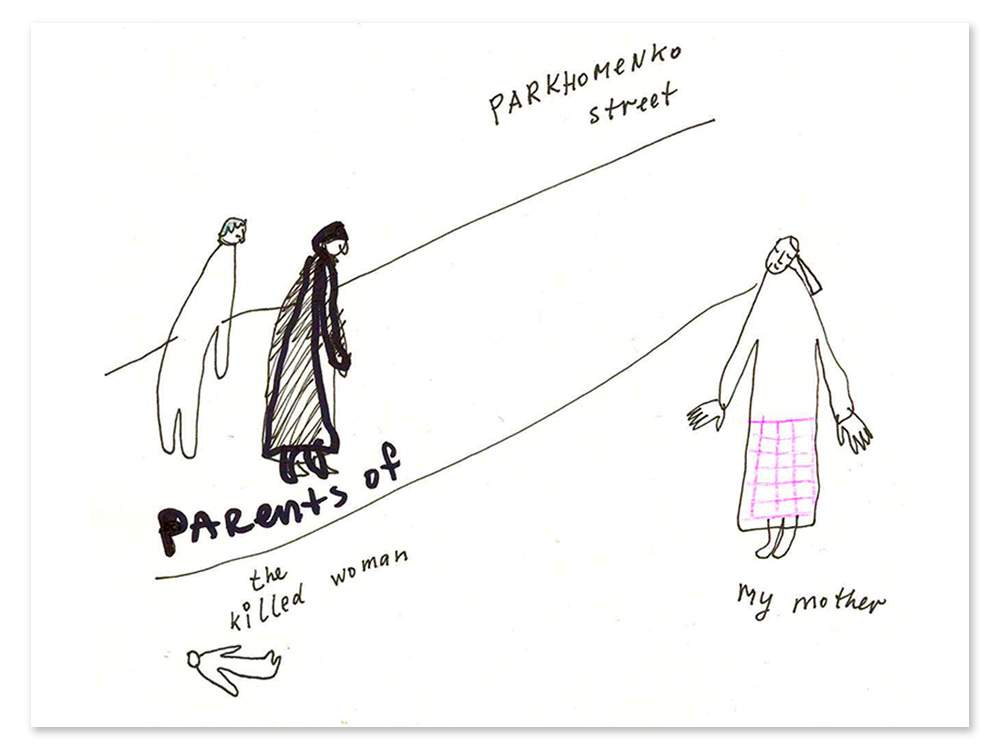

This checkpoint has particular significance for Alevtina Kakhidze, who is travelling with me. It was the checkpoint her mother was heading for a few days after their last conversation.

That was four months ago.

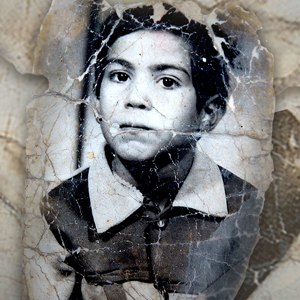

Alevtina is a well-known Ukrainian artist. She lives in the north of the country; while her 70-year-old mother Liudmila lived in Zhdanivka, in the eastern region controlled by Russian-backed fighters.

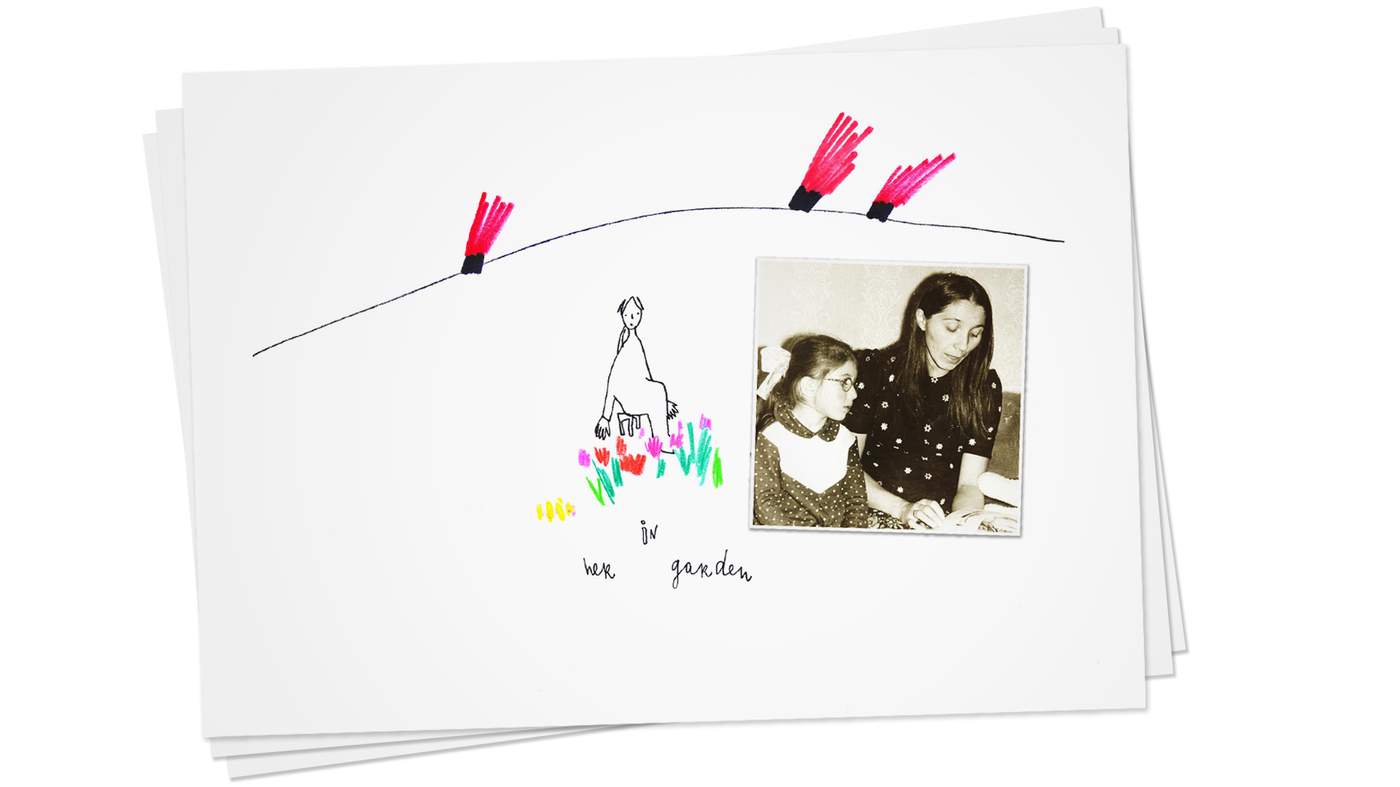

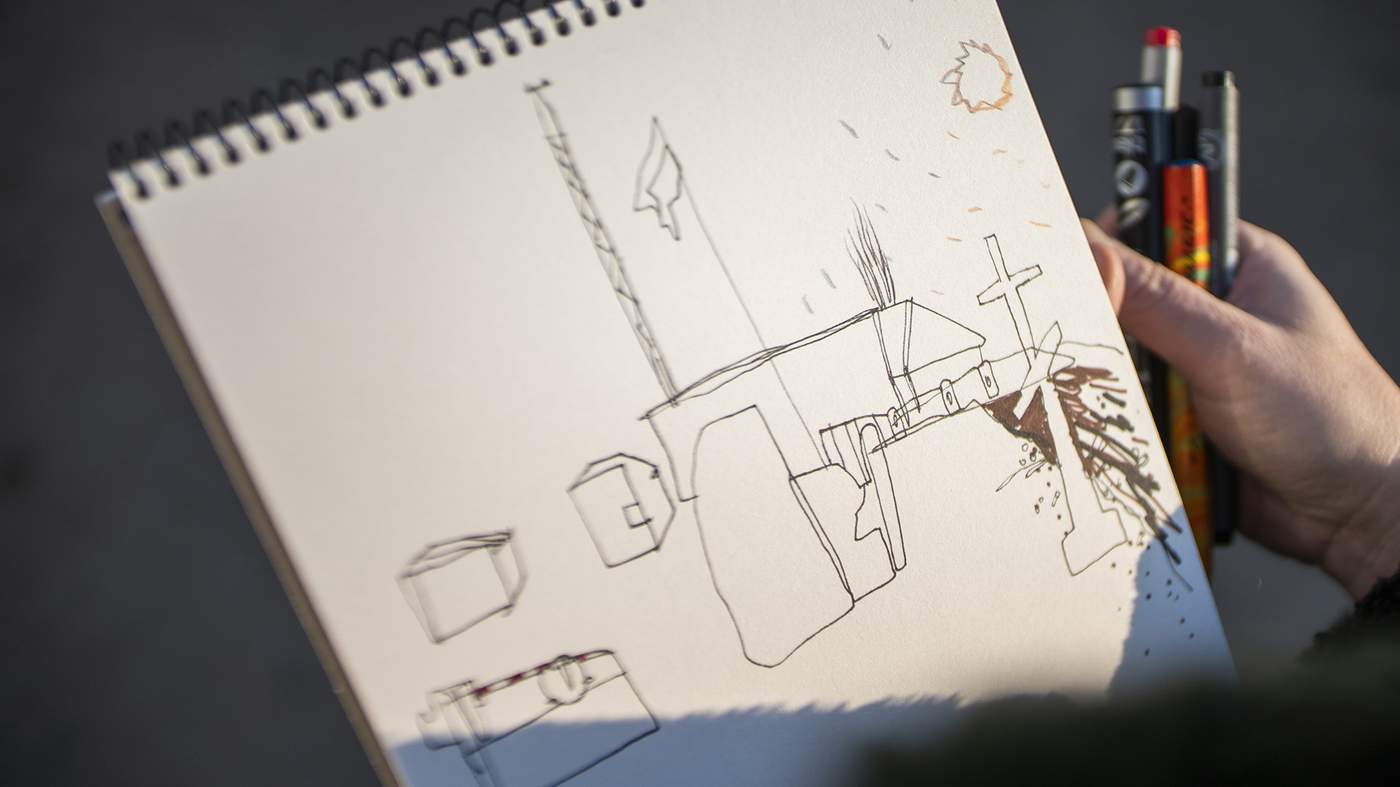

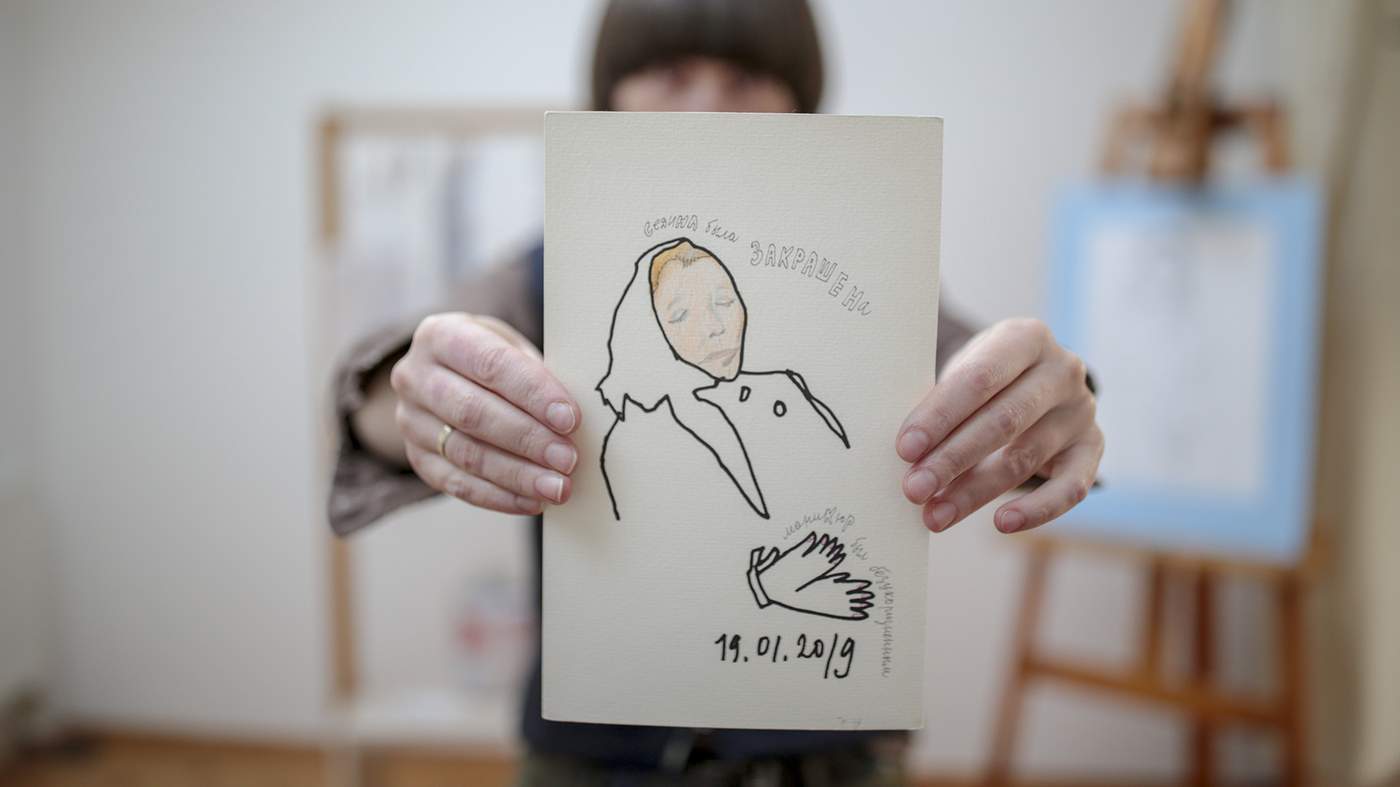

It was very difficult for them to meet but they spoke most days on the phone. Alevtina drew pictures of her mother’s anecdotes - a way for her to envisage Liudmila’s daily life in a conflict zone.

She created a Facebook page for the pictures and they became popular amongst those in Ukraine hungry for news about the breakaway territories.

One day in January this year, Alevtina was expecting a call from her mother. Her phone rang, showing her mother’s number.

But when Alevtina answered the phone, it wasn’t Liudmila on the end of line. It was an unfamiliar voice. A man.

“A woman whose phone I’m calling from has died,” he said simply.

Alevtina was in shock. “I couldn’t speak,” she says. “I didn’t know what to think - whether it was even true.”

She asked the man to call her back later when she had been able to process the news.

Since he had introduced himself as a separatist fighter, calling from Mayorsk checkpoint, Alevtina feared the worst. She knew that her mother had been planning to travel to the front line that week.

On 16 January Liudmila had got up at 04:30 to start this gruelling process. These trips were made in inhuman conditions. It took her about 11 hours to reach Ukraine-controlled territory, she had told her daughter in the past.

The trip would be necessary, though, if she wanted to receive her pension. That could only be done on government-held territory.

So once through Mayorsk checkpoint on the Ukraine-controlled side, she would have headed to the town of Bakhmut.

Alevtina and I travelled there to see it for ourselves.

Bakhmut used to be an undeveloped backwater, but now it throngs with people who have crossed the front line from Ukraine’s east, or who are waiting to return from the west. Dozens of businesses have sprung up - shops selling provisions and books for the journey across the front line; entrepreneurs running minibuses to ferry people right up to the checkpoint.

The queues that began at the checkpoints continue here at the banks and the ATMs.

There are many elderly people like Liudmila who have embarked on the same laborious journey for the same reason - to either collect their pension or to ensure the much needed money isn’t taken away from them.

For Ukrainian nationals living in the territories controlled by Russian-backed fighters claiming your state pension is not a simple process.

Ukrainian banks don’t operate on the breakaway territory.

And in order to qualify for them you need to pretend you actually live in a Ukrainian-controlled area.

And then you have to be ready for someone to knock on the door of that property every 60 days to check if you really do live there.

Except that knock might not come on Day 60 - it might come on Day 58 or 59. So, many rely on a local friend to ring ahead and warn them the authorities are in the area.

Then the dash to the front line begins.

Liudmila had originally planned to travel a couple of days later than she actually did, her daughter says. So Alevtina thinks she must have received such a phone call to warn her, and rushed to bring her travel plans forward.

Liudmila, like others living in the region, was also eligible for another pension - from the Russian-backed authorities, Alevtina says.

But at only $46 [£36] a month, it was nowhere near enough to live on, even when supplemented by the money she earned selling vegetables. So her Ukrainian pension, giving her an additional $65 [£50] a month, was essential.

The journey is so difficult and slow that not everyone can make it across and back in 24 hours.

Alevtina’s mother could have stayed with friends. But some have to stay in a hostel overnight - an added expense, and from what I saw from the one I visited in Bakhmut, very basic conditions.

Alevtina says she could have given her mother the equivalent of her pension. But she knew Liudmila would be too proud to take it. She says her mother fiercely guarded her independence and felt it was her moral right to claim the money owed to her.

But it came at a fatal price.

Liudmila fell ill on a bus as she neared the final checkpoint manned by the Russian-backed militia.

“Somebody tried to help her; she was put into a shelter on the front line. They even called an ambulance, but it didn’t manage to come in time.”

No-one knows what she died from but her daughter believes the strain of the journey had taken its toll. It took two days for Liudmila’s elderly neighbours to go and identify her.

Alevtina’s high profile in the country made it too risky for her to cross over to the territories held by the Russian-backed fighters.

“I made dozens of calls to the emergency services, the authorities and the secret service,” she tells me. “And finally, my mum arrived in our village… And we buried her.”

Human rights campaigners argue that the queues would be eased if the Ukrainian government worked harder to simplify the pension system for those living in the breakaway territories.

The government, for its part, says it tried to open an additional checkpoint to ease the queues but the Russian-backed forces wouldn’t agree to it.

But the authorities are also accused by rights groups of making it deliberately difficult in order to deter claimants. About 62.2bn hryvnias [$2.4bn] worth of pensions went unclaimed between August 2014 and September 2018, according to the Ukrainian NGO Right to Protection, which shared an official letter from the Ukrainian Pension Fund with the BBC.

In an interview with the BBC, Ukraine’s minister of social policy questioned whether those living in the areas controlled by Russian-backed fighters should be claiming state pensions in the first place.

“Everyone who’s pro-Ukrainian has left, and those who want to claim pensions on both sides have to put up with [the conditions],” Andriy Reva said in the report broadcast last month.

Andriy Reva

He said some residents there had helped perpetuate the fighting by allowing the Russian-backed separatists to use them as human shields.

“Honestly I don’t feel pity for them... not one of them. I feel pity for [the] soldiers and officers, and for their families, who were killed there.”

Mr Reva’s comments created waves across Ukrainian society, with some MPs even calling for his resignation.

Human rights activists argue that the civilians should be seen as hostages of war, not enablers of the conflict.

Mr Reva added that the priority was to end the fighting.

“The main option to prevent those people from suffering is to stop the war. And to stop it - the occupiers must get out of the territory of Ukraine and that’s it. And people will stop suffering.

“There are Minsk [peace deal] agreements, the formula is clearly defined in those. But even the first point [of the agreement] - the ceasefire - the gangsters do not fulfil. Because Moscow does not set them such a task.”

Ukraine’s new president Volodymyr Zelensky has also said he wants to end the fighting.

“Our first task is to achieve a ceasefire in Donbas,” he said during his inauguration address on 20 May.

Volodymyr Zelensky

He has stated that Ukraine must “give a hand” to those living in the occupied territories. But he did not provide any details.

As a political novice - Mr Zelensky is best known for starring in a satirical TV series in which his character accidentally becomes president - it is not yet clear how much will change under him. His campaign did not focus on any concrete policy proposals.

His landslide election was, however, a clear message to former incumbent Petro Poroshenko that Ukraine’s electorate is frustrated, not just with corruption, but also with the war.

The conflict began in 2014 when Russia annexed Crimea to the south, exploiting a political vacuum in Ukraine. Russian-backed fighters then seized Luhansk and Donetsk - the Donbas region - in the east.

Both Crimea and Donbas are strategic and symbolic gains for Russia. Annexing Crimea gives Russia better control of the Black Sea with its deposits of natural gas, and Donbas is home to most of Ukraine’s coal mines.

Ukraine describes the conflict as a “Russian invasion”. Western governments accuse Russia of helping the separatists in the region with regular troops and heavy weapons.

Despite strong evidence to the contrary, Moscow denies that, while admitting that Russian “volunteers” are helping the separatists.

In April, Russian President Vladimir Putin signed a decree making it easier for those living in Donbas and Crimea to get a Russian passport.

Mr Zelensky declared this a hostile act, calling on the international community to react with sanctions.

A ceasefire in eastern Ukraine was declared in 2015 but is regularly broken by both sides.

The fighting has killed around 13,000 people. Three thousand of them have been civilians, the UN said in February.

In Bakhmut, the town Liudmila was heading for on her ill-fated final journey, I say goodbye to Alevtina.

I want to see more, so I am shown around by a local student, Denis Rudenko.

His university is called Horlivka’s Institute of Foreign Languages. But confusingly it is no longer based in Horlivka.

After that town - 40km (25 miles) away - fell to the Russian-backed fighters in 2014, part of the university decided to move into Ukraine-controlled territory.

Denis says he has also moved from his hometown of Horlivka to Bakhmut.

“When you don’t see any future there… you see only one option: to run away somewhere where at least there is a chance for a future.”

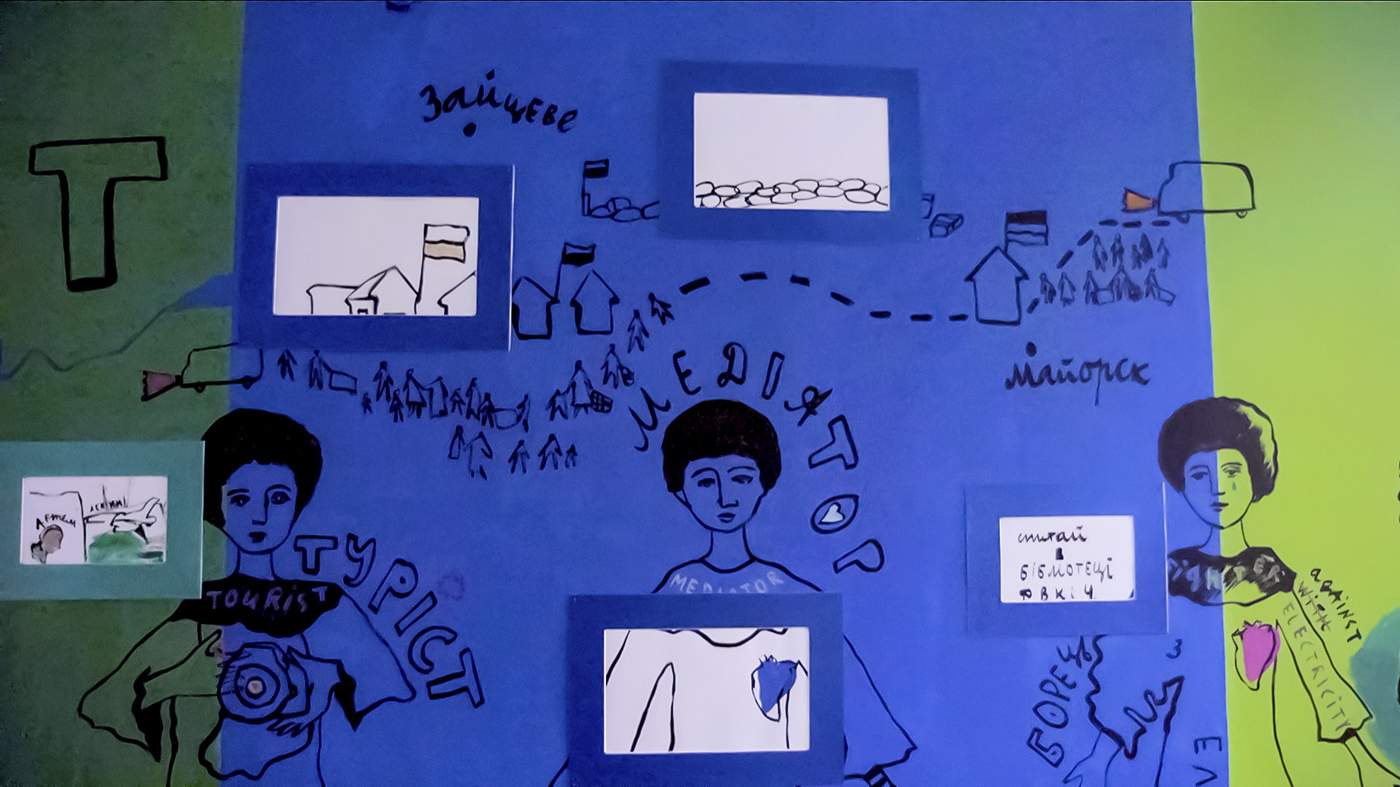

On one of the walls inside the university is a mural of a woman trying to cross the front line.

“It was made by a famous Ukrainian artist,” says Denis. “Alevtina Kakhidze. We are so lucky that she chose our town for her work. I helped a bit with that project - she brought so much inspiration.”

Denis now organises art events for local young people, which attract youngsters not only from Bakhmut, but sometimes from the territory controlled by Russian-backed separatists.

His aim is to give visitors a global perspective on the conflict - many of those coming to the events have never left their home town.

He hopes the projects will break down boundaries.

“Maybe it’s just little steps, but I feel they make a difference, make little changes.”