At this point the Football League was barely 25 years old, Wembley Stadium was still to be built and there hadn't even been a World Cup.

Yet scores of British soldiers would clamber over the top to chase down what would be their last pass.

Football was to play a fascinating role during World War One, from England internationals helping to form special Footballers' Battalions to the emergence of the women's game, as well as the morale-boosting effect the sport had on the troops both deep behind the lines and all along the front.

Immersed in it all was one footballing family.

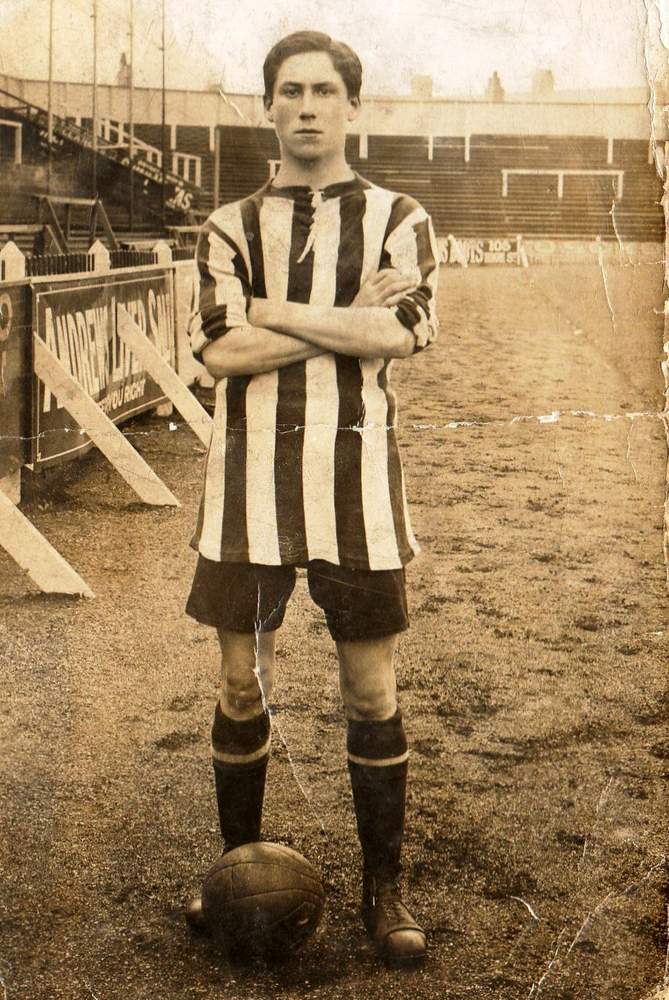

At the outbreak of war Jimmy Seed was 19. Life was good.

He had just earned a contract with Sunderland and escaped a miserable, unrelenting life as a coal miner.

"I was thrilled to sign professional forms for the side that had been known as the Team of all Talents, one of the biggest clubs in the land," Jimmy said in his book The Jimmy Seed Story.

"I was supposed to receive a signing-on fee of £10 but was only given £5 for some reason. My three months' summer vacation wages were £1, which was just enough to get by on at the time, as I lived at home with my parents. It was with joy I folded my miner's clothes for the last time. I was a professional footballer."

Sunderland were already five-time league champions and Jimmy didn't care about the sneaky deal which deprived him of £5 (almost three times the average weekly wage).

Football, and Sunderland, was his life. He went to games at Roker Park with his four brothers and now the club was his work as well as his hobby. Football was huge and Jimmy Seed was part of the most exciting period the sport had ever known.

But it wasn't the smoothest of journeys. Jimmy had "failed hopelessly" in his first trial. He had to borrow boots which were too big and played out of position at centre forward. The match itself came after a full night shift at the colliery.

"I did nothing and realised as I dressed after the trial in readiness for another night shift that Sunderland would not be interested in me," said Jimmy.

"I was in low spirits because I had come to loathe working in the pits."

But his impressive exploits as a teenager with Whitburn's first team soon led to a second chance, this time playing in his best role as an inside forward. He scored a hat-trick in a dazzling performance.

"Life in the coal mines was dire," Jimmy's grandson James Dutton, 62, told BBC Sport.

It's difficult to express how awful it was. Football was like a way out of hell.

"I know he hated it. He said it was an awful existence and couldn't wait to get out."

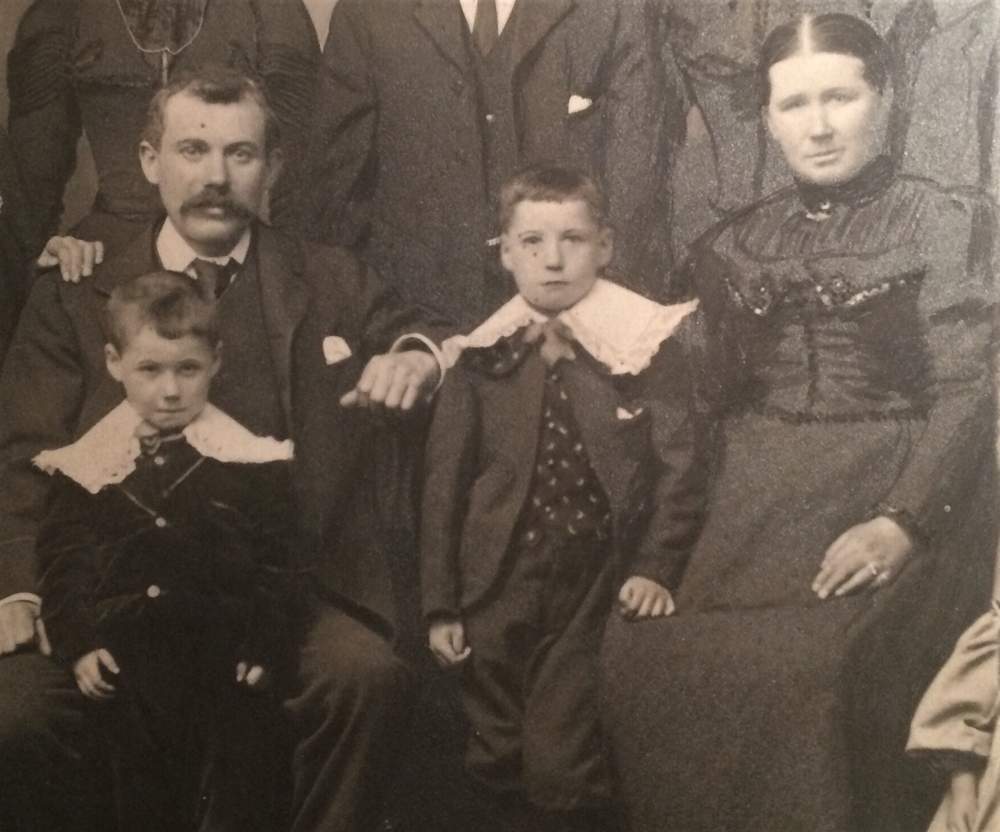

But a mining life was the expected path for the Seeds, a working-class family who had relocated from Blackhill in County Durham and settled in Whitburn in 1897, two years after Jimmy was born.

Jimmy's dad, Anthony, worked in the papermaking industry in Shotley Bridge, but was increasingly concerned about the future of the mill as manufacturing techniques moved on. There were five sons and five daughters to support.

Jimmy (left) and Angus with parents Anthony and Elizabeth

Mining at the Whitburn Colliery provided relative security but Jimmy had other plans. He was born in what he later described as "England's richest soccer nursery", and lived a couple of miles from Roker Park. He said he could "hardly fail to follow the soccer trail because in Whitburn soccer is meat and drink to all the boys".

The Seeds had the football bug, in particular Angus - one of Jimmy's four older brothers - as well as the youngest of the 10 siblings, his little sister Minnie.

But Jimmy's joy was short-lived. In April 1914 he was a professional footballer, yet he never got the chance to play for Sunderland's first team.

After almost 18 months playing for the reserves, fantasy football was soon to be replaced by the horrible reality of war.

And footballers were expected to play their part.

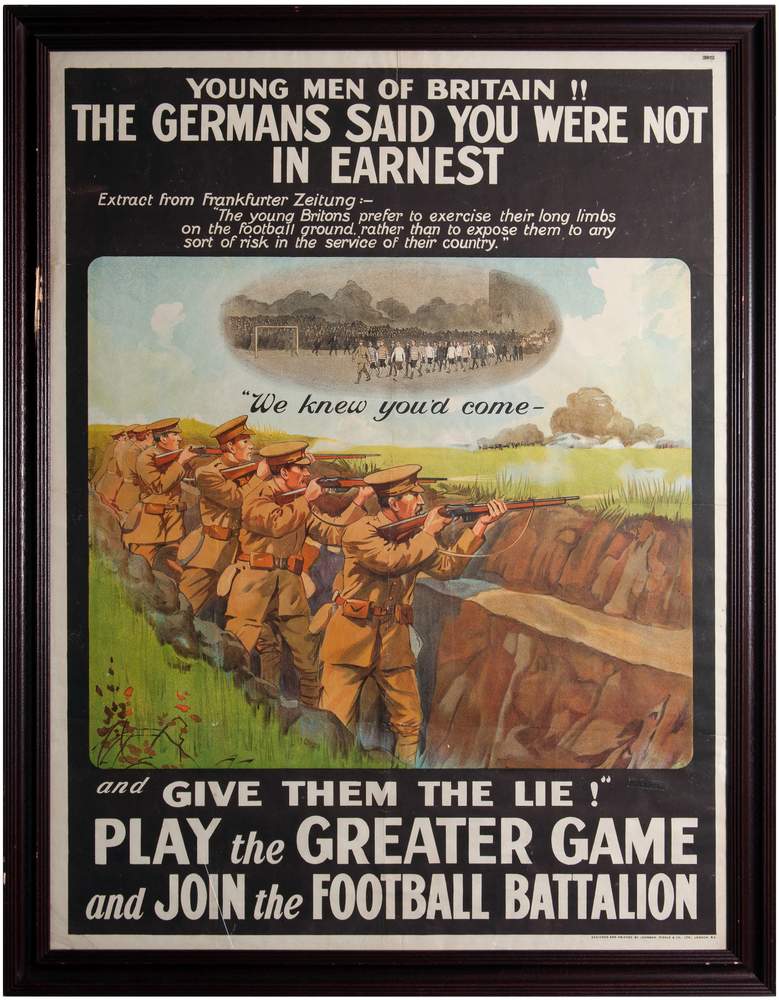

Spectators were asked to leave the terraces and rush to recruitment stations - and football's authorities had a duty to get them there.

When they weren't seen to be fully backing the war effort, the game's place in society and its sense of morality was questioned.

"Before the war there was an undercurrent of worry about whether lots of people watching football was good for the nation and the Empire," Dr Alexander Jackson, collections officer at the National Football Museum, told BBC Sport.

"There was the idea, especially of the upper classes, that sport should be played and not watched if it was going to have any value to society.

"Football was attacked early on because it was seen as keeping people away from going into the army."

In Sunderland, Lord Durham even said that he wished the Germans would drop bombs on Roker Park to encourage men to think about where they should be.

Football, unsurprisingly, took offence. Locally the game's governing body made efforts to compile figures on just how many men the sport was contributing to the cause.

This, Dr Jackson said, was an "information war" on the home front.

In newspapers, the debate raged as football, rugby league and cricket were not immediately suspended. In London, the Evening News went so far as to cease printing its football edition.

Outside the football grounds there were protests, yet inside speeches were delivered by military spokesmen encouraging spectators and players to take up arms.

Footballers answered the call

The great Corinthian FC side of the day - one that inflicted the heaviest-ever defeat on Manchester United, whose colours Real Madrid adopted and style spawned a club by the very same name in Sao Paulo - were one such team.

They returned from a tour of South America, dodging a German gun boat on the way, to fight.

Thirty-four Corinthian players would perish in World War One.

But it wasn’t just the amateur game that responded - there were 'current' international players too.

Fourteen men who had represented England during the 1913-14 season went on to serve king and country in the war.

And, from the professional game, Huddersfield Town's Larrett Roebuck died serving with the 2nd Battalion York and Lancaster Regiment in France just weeks after fighting began.

The talented full-back, 25, was initially recorded as missing in action and eventually "presumed dead".

Among the carnage, a touch of Christmas cheer was brought to the front.

Incredibly, on Christmas Eve deadly rivals sang carols to each other from their trenches.

It's to this peaceful soundtrack that it is said football brought both sides together for what Fifa describes as "one of the most celebrated" matches.

Unofficial truces undoubtedly took place on Christmas Day, with presents exchanged and makeshift balls kicked around in no man's land.

But the full-scale match itself, an event further promoted by much-loved BBC comedy series Blackadder Goes Forth, Paul McCartney's song Pipes of Peace and a popular Christmas advertising campaign, is most likely a myth that has turned into legend.

"The Christmas truce is amazing in being one of the most recognised things from World War One in terms of capturing popular imagination," said Dr Jackson.

"It is embraced because of the idea that football is a means of bringing people together. At that level you can see why, philosophically and on a sentimental level, it is taken on."

Fraternising with the enemy, while a romantic notion and one that was widely publicised in newspapers at the time, infuriated High Command.

Repeat offences would be punished by Court Martial. This was all-out war.

It's with a Christmas backdrop that professional footballers began to commit to the cause in greater numbers in England.

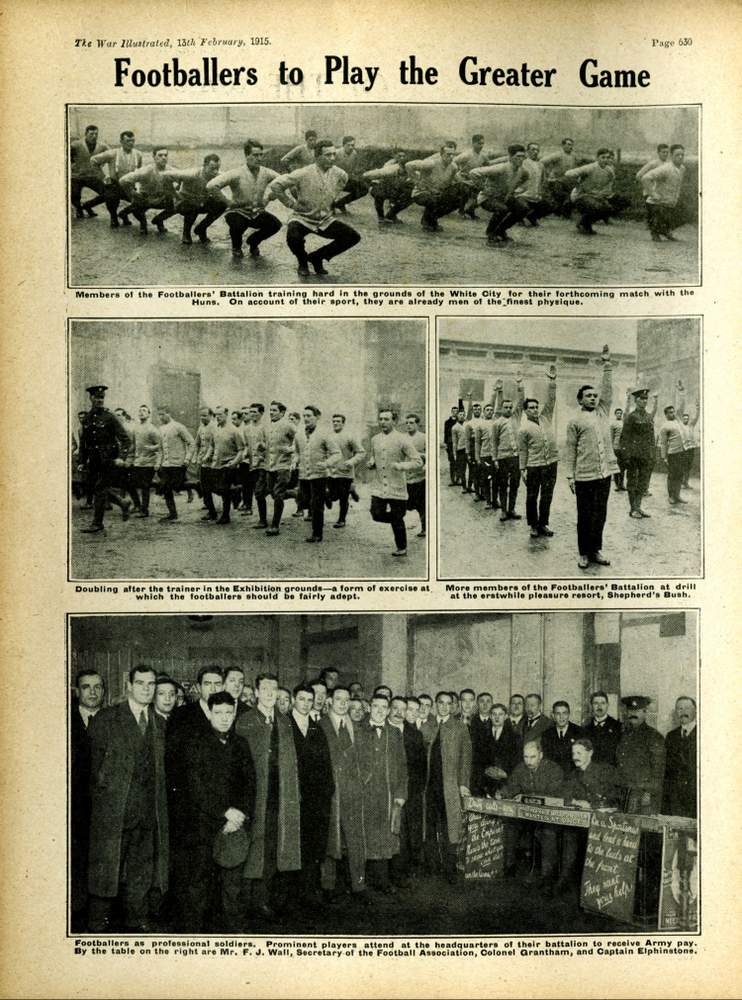

Within five months of war beginning, the 17th Middlesex regiment was raised - it would famously be known as the Footballers' Battalion.

Among its ranks was Jimmy Seed's big brother, Angus.

On 15 December 1914 a meeting was held at Fulham Town Hall to try to get those involved in the game to think more about 'doing their bit'.

It was not designed to be a recruitment meeting.

But by the end of a series of speeches, including an address by Football Association president and five-time FA Cup winner Lord Arthur Kinnaird, 35 men from 11 clubs enlisted - 10 of which were Clapton Orient players.

The 17th Middlesex - which also boasted football and military pioneer Walter Tull and future Wolves and Notts County manager Frank Buckley - was one of a number of 'Sporting Battalions' to be formed.

The 16th Royal Scots, better known as McCrae's Battalion and made up of a number of Heart of Midlothian players, was formed a month earlier in Edinburgh.

These were examples of how the game, its stars and the emotional connection to clubs were being used in propaganda to appeal to those considering joining the fight.

It was a familiar story for many and the Seed family were no exception.

Angus was a reserve player with Reading in 1914 but signed up as the recruitment drive proved an astounding success. The call for volunteers had hoped to attract 100,000 men. Within two months, more than 750,000 signed up.

Angus was soon preparing for war and picking up tips for fitness training, as he explained in a letter to Reading's secretary.

"We are getting on fine here," said Angus. "And if they keep giving us the drills we had this morning, we will have muscles like stones.

"It would do some of the boys good to come down here, it would harden them up a bit."

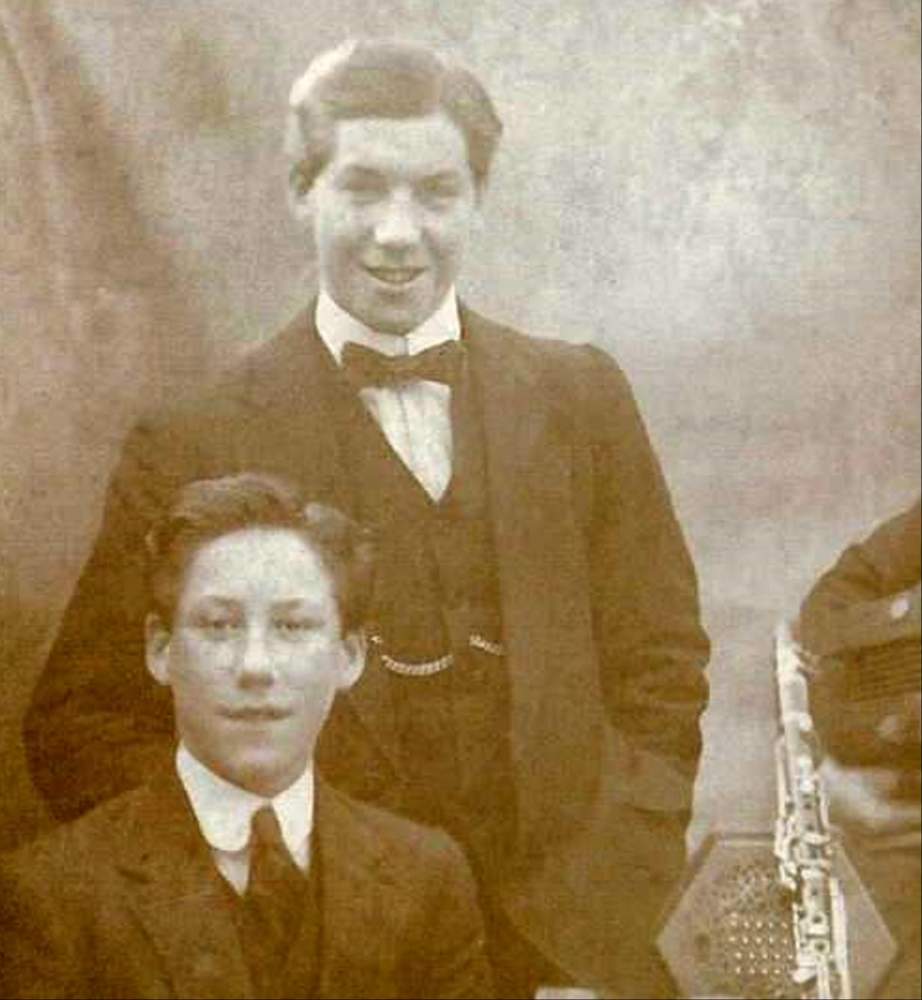

Jimmy (left) described Angus as his "champion"

He became part of the battalion's musical band, who also doubled as stretcher-bearers. And although usurped by Jimmy - who took his place in the local team as a young teenager - on the football field, Angus would excel on the battlefield.

Jimmy was the family's footballing star, but idolised Angus, reflecting that his big brother was "always my champion".

At the end of the 1914-15 season, Jimmy, who had just turned 20, finally joined up.

"He would have seemed to be one of the least likely people in the world to sign up when he had just got a contract with Sunderland," added his grandson James Dutton.

But Jimmy's priorities had changed.

Football had ceased to be the most important thing in life for me. Britain and Germany were at war and playing football was no longer such a thrill."

Jimmy volunteered alongside fellow Sunderland players Tommy Thompson and Tom Wilson, joining the 63rd Northumbrian Division in the Cycling Corps. They trained in Gainsborough, Lincolnshire.

Unsurprisingly, the trio formed the nucleus of a particularly useful team. They beat Grimsby, then a Football League side, in a friendly and quickly became known as the best football side in the military.

The month after Jimmy volunteered, in May 1915, the second Footballers' Battalion - the 23rd Middlesex - was formed.

Coaches, referees and fans would go on to serve alongside their heroes. Truly a one-for-all approach. By 1918, approximately 4,500 men would serve the 17th Middlesex, with around 900 never to return to Blighty.

A total of 1,500 men lost their lives across the two Footballers' Battalions.

Back home, as football carried on, special leave was granted to players each week to allow them to swap combat boots and military training for football boots and league and cup matches.

It proved to be an important concession.

"It allowed balance," said Dr Jackson. "Players weren't leaving their clubs in the lurch and clubs had players that could help draw a crowd."

And so the 1914-15 campaign controversially continued. Football absorbed more criticism and by the end some clubs were teetering on the edge of financial collapse because of dwindling crowds.

Everton won the league title and Sheffield United overcame Chelsea in the FA Cup final at Old Trafford in April 1915 - a match known as the Khaki Cup Final because of all the uniformed soldiers in the crowd of nearly 50,000.

Then, professional football stopped.

All competitions were suspended until peace was restored. Players were no longer paid, although unofficial regional competitions would be held for the duration of the war.

These games raised charitable funds for the war effort and matches served as a distraction for civilians and soldiers alike.

Jimmy had just over a year training in England, by all accounts having a pretty grand time, before being drafted to France with the 8th Battalion West Yorkshires.

By that time, his brother Angus was already a war hero.

During a German attack on 1 June 1916, Angus dragged several wounded men, including the Arsenal assistant trainer, Private Tom Ratcliff, back to the British lines while under heavy fire.

Ratcliff had been buried by an explosion, but Angus rescued him and was later awarded the Military Medal.

Later that month Angus was badly injured in his right hip by shrapnel. It was an injury that effectively ended his professional football career.

Footballers and Footballers' Battalions were clearly fully playing their part in the war effort, dispelling any early talk of not fulfilling their duty.

The idea behind the special units was an extension of the Pals battalion concept, many of which had been raised in northern towns and cities, aimed at assuring recruits that they would serve alongside people they knew. Targeting camaraderie as part of the recruitment process was key. And it worked.

In South Yorkshire, the Sheffield Pals ran through drills at Bramall Lane.

And, in south London, a poster calling on the 'Men of Millwall' was particularly direct, reading: "Let the enemy hear the Lions' roar. Join and be at the final and give them a kick off the earth."

"It was tailored recruiting, picking up on different levels of identity," said Dr Jackson.

"Military messages and posters incorporated sporting terminology with phrases like 'play in the greater game and join the Footballers' Battalion', and 'positions need to be filled in all areas of the team, join up and play your part'."

Seven days of heavy bombardment had left the British military commanders convinced success was a formality. It would be a simple matter of strolling forward and claiming victory.

But the pounding had made little impact on the heavily fortified defences and machine gun positions.

The Germans emerged from their dugouts relatively unscathed and the enemy were butchered in catastrophic numbers. On one of the most infamous days of World War One, British fatalities totalled 19,240 among the 57,470 casualties.

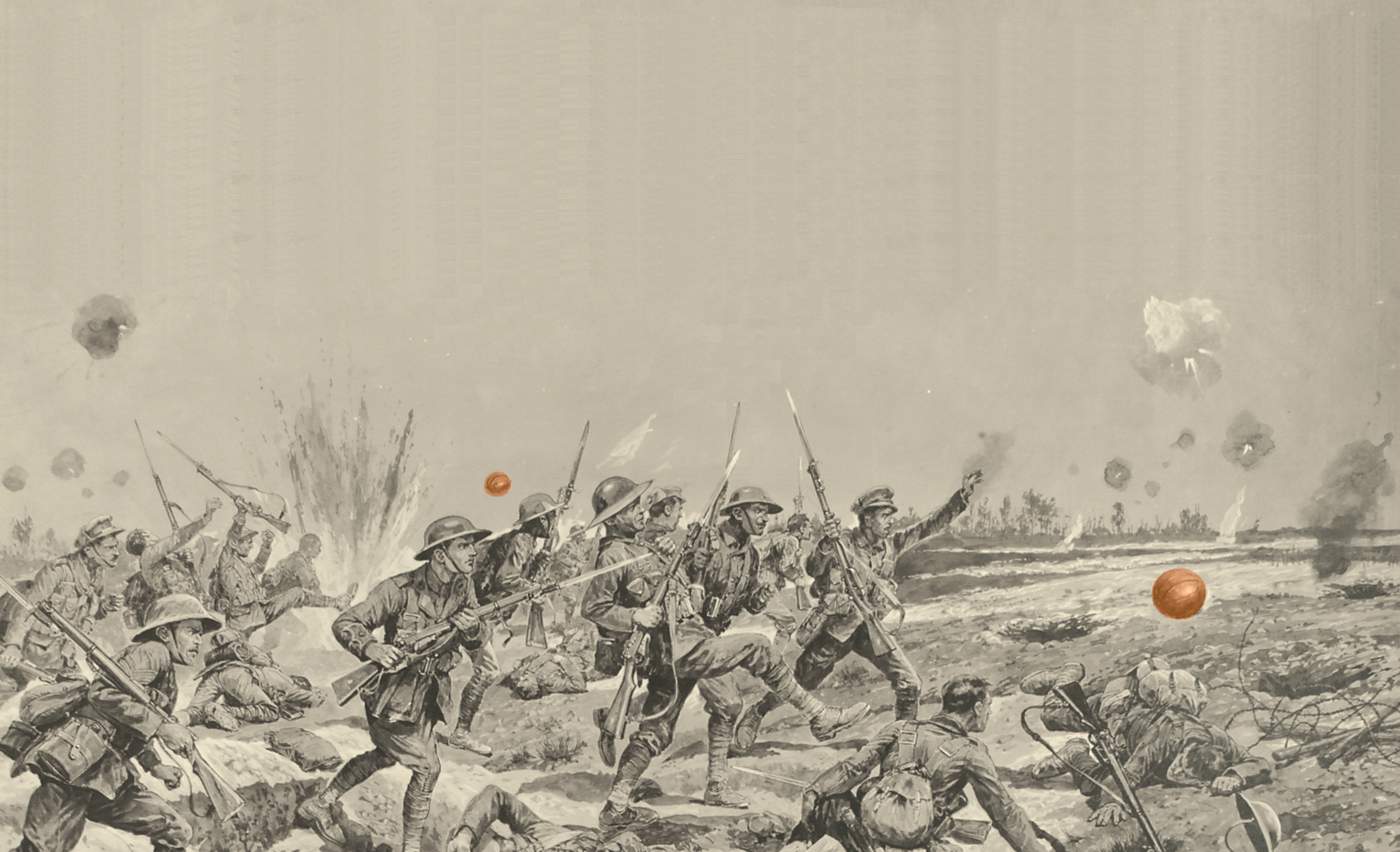

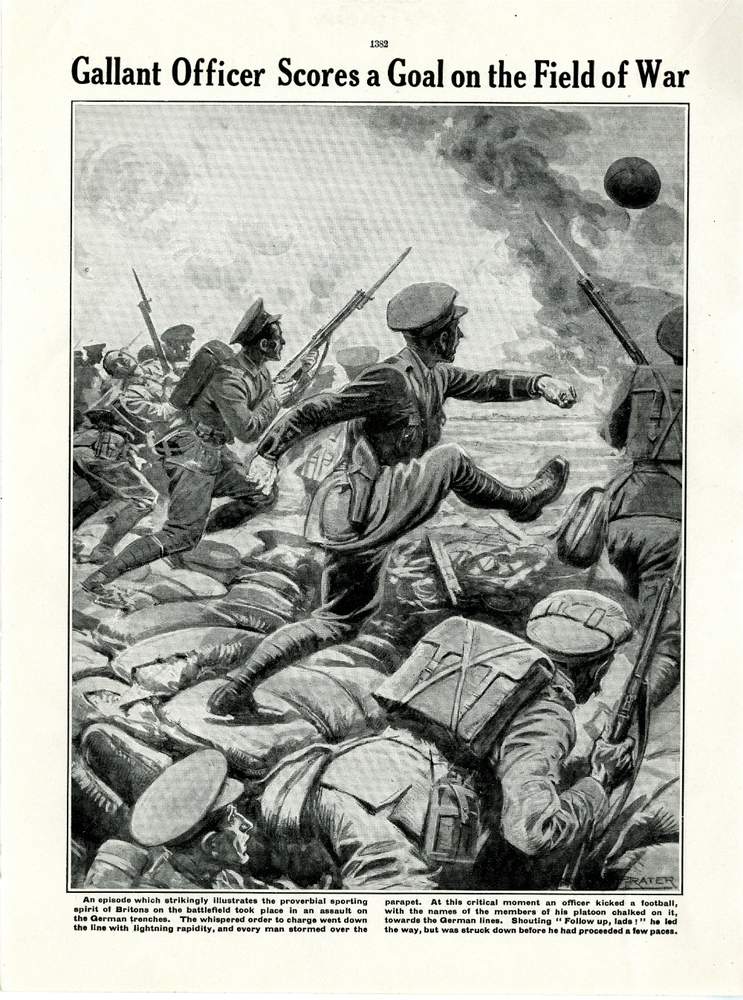

Captain Wilfred 'Billie' Nevill led the men of B Company of the 8th Battalion East Surrey regiment over the top. His approach was different, though. He gained permission from his superiors to use two footballs to lead the attack.

The balls were a focal point. One had “The Great European Cup-Tie Final. East Surreys v Bavarians. Kick off at zero” written on it. The other simply said “NO REFEREE” in large capitals.

They were a desperately-needed distraction using a common love of the beautiful game to hide the most hideous of prospects.

Petrified but still bravely breaking forward, hoping to nick a one-goal lead as they chased a ball over the top was not the gameplan - surviving the unfolding mayhem was the only thing on their minds.

It was the last pass that many of the men would ever chase. The East Surreys achieved their goal, but suffered a heavy death toll, Billie Nevill among them.

Nevill's unusual tactics were seized upon by the British newspapers. It was propaganda gold but there was no disguising the gruesome failure of the battle. The Germans had their own spin, dismissing it as pure foolishness in war.

The football influence ran far deeper than the Footballers' Battalions.

Bradford Park Avenue player Donald Bell would go on to earn the Victoria Cross for "most conspicuous bravery" during the Battle of the Somme.

On 5 July, Second Lieutenant Bell was advancing with his troops along a trench known as the Horseshoe.

There, they came under heavy machine-gun fire.

The Victoria Cross was awarded to 49 British soldiers during the Somme

Bell and two others - Corporal Colwill and Private Batey - launched a sneak attack on crews manning the weapon. Bell shot the gunner with his revolver and a grenade was thrown to help the British gain ground.

"I only chucked one bomb," Bell wrote to his mother, "but it did the trick."

Five days later, aged 25, Bell was killed making a similarly audacious raid on an enemy trench. His VC medal was presented to his widow by King George V.

Losses on both sides were monumental during the Battle of the Somme.

A German war grave at Neville-St Vaast is the final resting place for almost 45,000 soldiers, of which 8,000 are unidentified.

Scattered among the sea of crosses, which marks a grave containing four bodies, there are 129 which stand out.

They are stone graves, featuring the Star of David and representing Jewish-German soldiers.

While German Jews fought alongside all other Germans against the Allies in France, one of Jimmy Seed's Sunderland team-mates refused to pick teams.

Norman Gaudie, a 28-year-old accounts clerk, was a committed pacifist and was to be imprisoned for his beliefs.

While some objectors were granted exemption and served in non-combat units, as Burnley's England international Edwin Mosscrop did, or contributed to the war effort by working in factories or on farms, like West Ham's Leslie Askew chose, Gaudie was steadfast against any involvement.

Gaudie's religious beliefs meant he felt "bound to disobey any military orders in loyalty to those convictions, which are based on the spirit and teaching of Christ".

Not everyone answered Lord Kitchener's famous call

His refusal saw him arrested, fined and locked up in the cells of Richmond Castle in Yorkshire, before being shipped off to Boulogne, France, where he described the conditions as "foul and disgusting beyond words".

It's there on 'active duty' that refusing a direct military order could see him sentenced to death.

And he was.

But faced with the firing squad he - and his fellow 'conchies' - were given a reprieve by Prime Minister Herbert Asquith as news of their treatment had caused public outrage in England.

The last-minute intervention meant Gaudie and the other absolute objectors instead faced hard labour in prison.

Meanwhile, Jimmy Seed was by now fighting his own personal battle - as well as the bigger battle.

"After arriving in France in the summer of 1916, he struggled, suffering with bad periods of depression, which were only relieved by playing football," explained grandson James Dutton.

"He was captain of his battalion team and his good friend Tommy Wilson was captain of another battalion of the Leeds Rifles. These football games really helped him."

Like so many of those that served, Jimmy remained secretive about many of the details of his time in the army. But his passion for football never wavered and undoubtedly helped him deal with war.

"I am sure they played whenever they could," added Dutton.

"There was an impression all soldiers were shoved in trenches until they died. But they went back behind the lines for rest and relaxation and played football then."

But World War One soldiers were not exclusively engaged in trench warfare.

By July 1917, Jimmy was in Belgium.

"He and his fellow comrades were sleeping in a basement of a bombed out building in Nieuwpoort, near Ostend, and the Germans dropped mustard gas from an aeroplane," said Dutton.

"It was a major incident. Nearly 100 soldiers died and about 700 were hospitalised, including Jimmy."

Jimmy underplayed his time in the army as "worrying and uncertain days".

The only aspect of soldiering he missed was the friendship and the football.

Football helped me to escape from periods of mental depression."

Whenever the soldiers were afforded a reprieve from the trenches, they could be seen playing behind the lines.

Even with shells falling nearby, they would continue. It perplexed the French troops.

"Certainly the French took the view of 'what are these crazy British guys doing?' as often they would be seen playing football behind the lines," said Dr Jackson.

"The French army at the time didn't integrate sport into their philosophy, and during the war it began to be adopted because they could see the health benefits and how it was serving as a distraction."

World War One would prove instrumental in spreading the popularity of football among the French masses, as it was previously seen as a sport played by Anglophiles and the elite middle class.

"Through constant exposure and playing against British army teams the French got quite good, quite quickly," added Dr Jackson.

"The war did pave the way to a post-war football boom."

And it was not just the French who latched onto football during the war. An estimated 250,000 Belgians fled to the UK following the German invasion of 1914.

The game was embraced as a favourite pastime, and football did its best to welcome the monumental influx of refugees.

Blackpool FC even changed the colour of their kit to that of the Belgian flag in an effort to make them feel more at home.

Football was also used as a way to raise charitable funds, with Belgian soldiers coming together to form a team that toured Britain.

The Belgians got so good that they went on to win gold at the 1920 Olympic Games, then the biggest international prize in world football.

And, 100 years on from the end of the Great War, France won their second World Cup, having overcome Belgium at the semi-final stage of the competition in Russia.

By 1918 almost a million women worked in munition factories and they were encouraged to get active. They did.

Football proved a popular leisure activity, but their interest would not be confined to lunch-break kickabouts.

Work teams were founded, charity matches played and competitions established as games pulled in crowds of tens of thousands.

Football, previously deemed unsuitable for the dainty and delicate women, had found its stage.

"Before the war there was a lot of male hostility to the idea of women playing football," said Dr Jackson.

Attitudes towards women and what they could do in society changed during the war.

"There was a huge amount of charitable work during World War One at all levels of British society. Women involved themselves, not just as supporters, but by becoming the attraction and women's football proved popular."

With her brothers away on their European tour of duty, Minnie Seed stole the spotlight. She worked in a munitions factory but had the family's sporting genes. She represented numerous sides in her native North East and beyond - including the most famous of all, Dick, Kerr Ladies.

Jimmy's grandson James Dutton said: "Minnie was playing football in front of crowds of 30,000 at St James' Park and became something of a local celebrity.

"Jimmy was quite an old fashioned fellow and I don't think he would have approved of women playing football. But he was on a disabled serviceman's pension after his gassing and this was what Minnie was raising money for, as well as working to help the war effort."

Minnie (bottom right) pictured with her team-mates

Some onlookers were more receptive to the new phenomenon of women's football. Ernest Edwards, sports editor of the Liverpool Echo, at least offered some encouraging, if heavily condescending, support.

"You doubtless wonder whether the playing of football by ladies has come to stay," he said. "I think their stay will be long in the land of football.

"They have a keen sense of the right thing to do, keep the ball on the turf, and show stamina that one could not have thought possible."

Not many agreed with Edwards' grudging praise. Most definitely not John Lewis, an FA council member who refereed the first game played by the Dick, Kerr Ladies team.

"After seeing the match and taking part in it, I have no hesitation in repeating the opinion I expressed last week," he said. "Namely that football is not a game suitable for women, and if they continue to play during the war I hope they will cease doing so when the peace is declared."

His views were not alone so, while women's football played an important role during the war and drew crowds of more than 53,000 after it ended, it was to be banned by the FA in December 1921.

Old prejudices of the game being unsuitable for females were the reason behind clubs being asked "to refuse the use of their grounds for such matches".

Incredibly, the shameful sanction was to last 50 years.

A shortage of manpower in the British Army saw the 17th Middlesex - which had been reinforced a number of times since 1915 - disbanded in February 1918, with troops bolstering other units.

Walter Tull, among the battalion's earliest recruits, a war hero and pioneering officer with the 23rd Middlesex, was killed a month later.

Tull, who overcame poverty and racism to become one of English football's first black players, was hit by machine-gun fire trying to rally his troops near Arras.

He was the first black man to command white troops.

While the men he led tried to recover his body, they never did.

"At this stage of the war, you knew that if you left someone out there you may never find their body again," said Dr Jackson. "And it was that love and care for a comrade, even after death, that said volumes about how much they respected him."

Unlike Tull, Jimmy Seed survived the war, but only just.

He had recovered sufficiently to be given the all-clear to go back to France at the end of August 1918.

Less than two months later he was gassed again, this time in Valenciennes, France, about 30 miles south east of Lille.

For Jimmy Seed, the rebuilding included his football career.

The gassings would affect him for the rest of his life - not least when he tried to resume playing way too early.

Jimmy was getting a train back to Wigan, where he was recuperating, and bumped into the Sunderland team on the platform.

His team-mates recognised him, explained they were a player short and asked him to make up the numbers.

"Foolishly he said, yes," explained his grandson James Dutton.

"But his lungs were not in good order. He had an appalling match in the Victory League (an unofficial First Division fixture).

"It went horribly wrong and, on the back of that, one of the Sunderland directors hauled him in and said 'we are going to let you go'. They suggested he went back to the pit so he could 'sort his health out'.

"That was heartbreaking and he was very depressed.

"It must have been astonishingly tough for him having survived near death and seeing his dream of being a professional footballer shattered in front of his eyes."

Jimmy said in his book: "I was hurt when I learnt that my poor display meant I was never to play for Sunderland again. Now I felt bitter for the first time in my life. I was 23, suspect in health and, worst of all, unwanted at Sunderland."

Like Jimmy, Sam Wadsworth was also left "broken hearted" by his boyhood club at the end of the war.

Aged 18, the then Blackburn Rovers defender from Darwen first tried to enlist to fight abroad. He was told to return a month later and encouraged by the Sergeant Major at the recruitment office to lie about his age.

He did, and followed his older brother Charles into the British Army ranks.

Wadsworth was wounded in action, but survived the war. His brother did not.

The atrocities left him physically and mentally scarred, suffering blackouts and grappling with post-traumatic stress.

Among several hours of autobiographical recordings he made in the 1950s, Wadsworth recalled those dark times.

"I had lost my only brother and my best friend and supporter," he said. "I began to realise that I had to forget all the rough times when we still stood up for more. I had to get on with my life."

At first, Wadsworth tried to do this with Blackburn - a club he proudly continued to play for at every opportunity during the war.

"They were glad of my services and I was pleased to play," he said of the matches he played while on leave from the Western Front.

"But when I came home for keeps the late Bob Middleton, manager of the Rovers, said 'sorry Sam, I have not a vacancy. You may have a free transfer'.

"That was all. What a blow. My life's dream had gone with the wind. I thought 'is this what I receive after nearly five years' service for my country?' I was very bitter."

That was where his career almost ended, with his father needing to convince the 23-year-old not to throw his football boots on the fire.

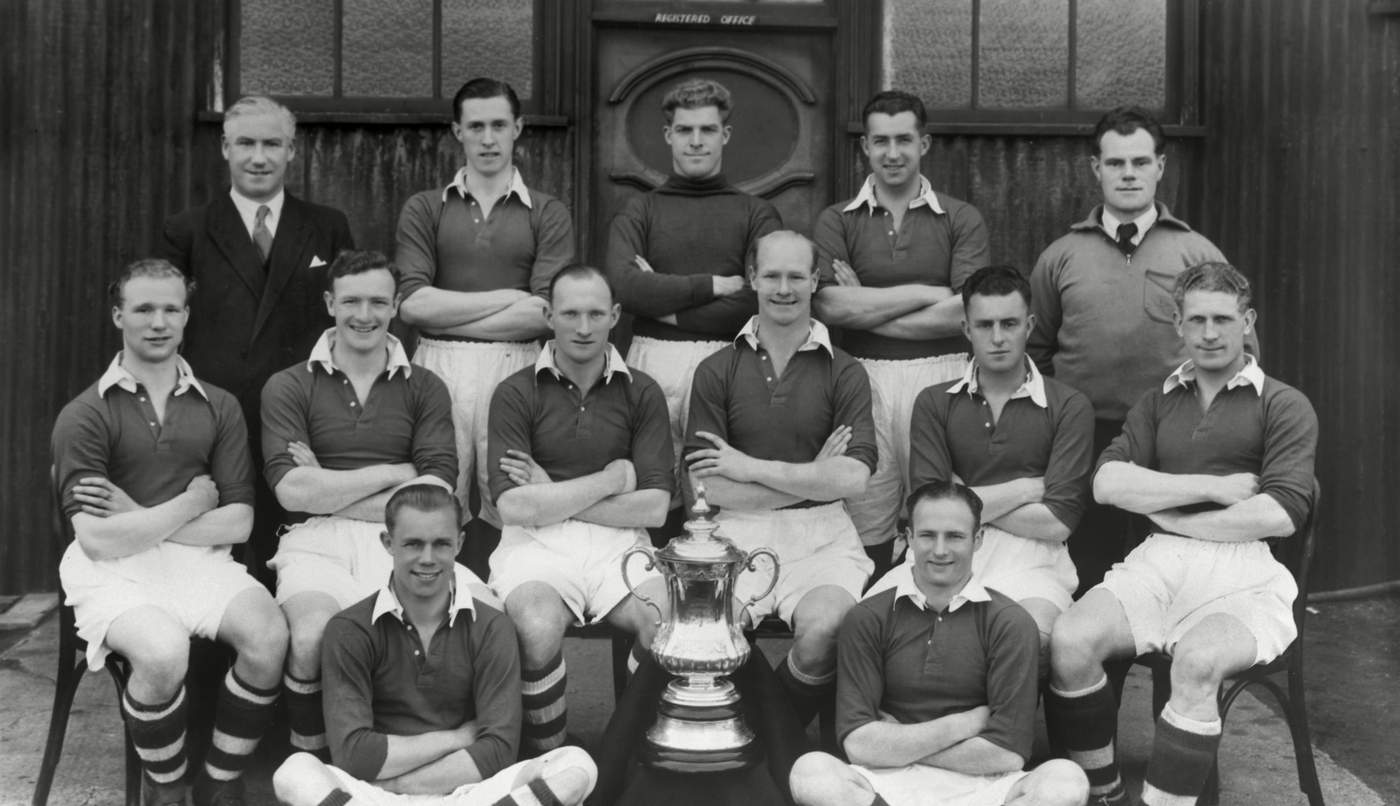

Instead, he dropped down to play lower-league football with Nelson before going on to join Huddersfield Town.

With the Terriers he won three consecutive league titles and an FA Cup in 1922 - a triumphant run which saw Huddersfield knock Blackburn out in the third round.

After Jimmy's second gassing, he was only deemed fit enough to be discharged from the army five months later, in March 1919.

The rejection by Sunderland left him devastated - and unemployed.

Manual labour and odd jobs replaced his pre-war career to make ends meet. He had kickabouts among the slag heaps with kids near the Whitburn Colliery and turned out for the local cricket team to keep fit.

But Jimmy never returned to the mines.

His salvation came with an unlikely move to Wales to play for Mid Rhonnda FC in the coalmining area of Tonypandy.

Jimmy's signing proved a masterstroke and in seven splendid months he helped the team win three trophies.

His rebirth was noted. Tottenham came calling.

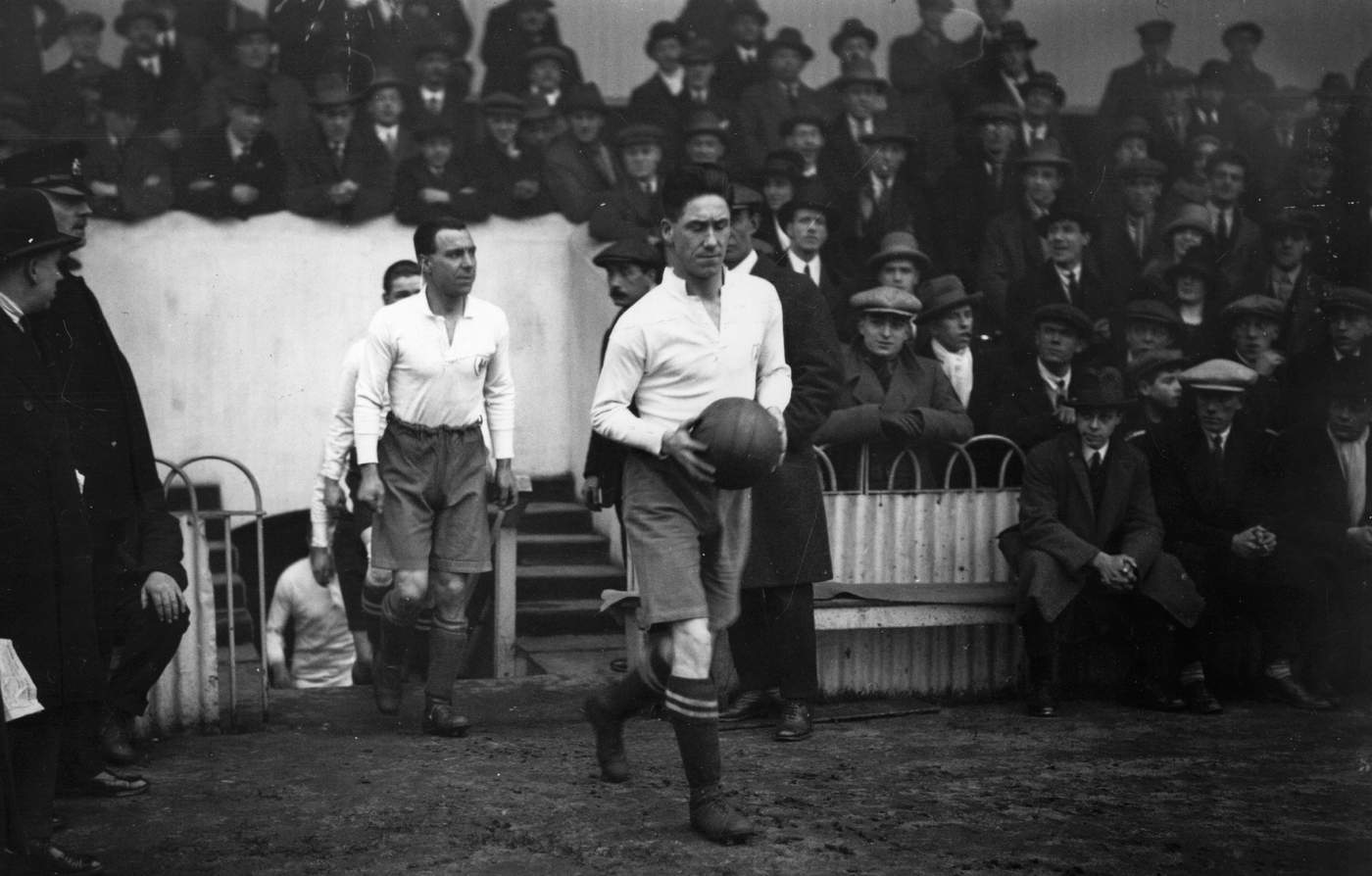

"It was like a dream," Jimmy recalled in his book. "Discarded by Sunderland before the start of one season, and now wanted by the famous Tottenham Hotspur club at the end of the next."

His move to London could hardly have gone better. In 1921 he was an FA Cup winner, then the prestigious pinnacle of a player's domestic career.

Jimmy made his England debut against Belgium in 1921

The same year he won the first of his five England caps. His redemption was remarkable.

Jimmy left Tottenham for Sheffield Wednesday in 1927 after "eight years without a grumble" when the club insisted on reducing his wages.

It proved a spectacular mistake by Tottenham. The Owls won eight of their 10 remaining games to avoid relegation - at the expense of Spurs, who capitulated towards the end of the season.

As captain, Jimmy then led Wednesday to back-to-back league titles in 1928-29 and 1929-30.

A knee injury forced him to retire from playing in 1931, first managing Clapton Orient and then Charlton, in 1933.

But the glorious success still hid dark times.

He was "encouraged" to resign in 1956 after a miserable start to the season. It was front-page news and he never truly got over it.

Jimmy's daughter Gladys went into labour on hearing that her dad had effectively been sacked. James Charlton Dutton was born the same day, three weeks early.

"Grandad really struggled after being sacked by Charlton," added Dutton. "But he still thought he was very lucky.

It's easy to say 'poor Jimmy', but he had a charmed life in a way and he seemed determined to live life to the full.

"Many who fought in World War One weren't nearly as lucky and he seemed to know it."

The war experiences, and the impact on his health, did not make it easy.

"Depression affected grandad throughout his life," said Dutton. "It came back to bite him a few times. He had problems with his lungs and his breathing and intense headaches.

"He never used to admit it was to do with the war and being gassed."

But Dutton has wonderful memories of his "play-mate".

Jimmy with wife Peggy and daughter Gladys

"Growing up I had heard of my grandad who had played football for England and won the FA Cup," he said.

"My first memory of him is from when I was about six and we moved back to live with my grandparents in Bromley. I thought he was a superstar.

"He was a rather striking looking chap with silver hair but he was just grandad to me.

"We would watch the horse racing together, play football in the garden and he taught me to play cricket and golf."

One day Jimmy suddenly opened up about his war experiences.

"We were gobsmacked," added his grandson. "I remember it clearly.

"I was about eight and he was talking about how they were trying to capture a bridge from the Germans. They were running down this bridge and two or three of his friends were killed running next to him.

"He was a bit choked up and stopped talking and that was the only time I remember him talking specifically about the war.

"Maybe he needed to get it out of his system, as he was getting older."

But the war was a time Jimmy, like so many others, wanted to forget. He cherished his football life.

"He was innovative and firm and fair," said Dutton. "He would explain his decisions and players loved him for that.

Jimmy Seed was revered as a special player and respected as a manager.

"Charlton made a huge amount of money through his transfer dealings, he believed in coaching players.

"He was something of a celebrity and he loved it. People treated him with such reverence. People would ask me to get his autograph, I was so proud of him.

"We became good chums. I was distraught when he died in 1966."

Sister Minnie and brother Angus were both survived by Jimmy.

Minnie married on Boxing Day 1923, with Jimmy missing an away game against Huddersfield to attend the wedding. Minnie had one son, Thomas, and died in 1948.

Following the war, Angus became Aldershot's first-ever manager and was Barnsley boss for 16 years from 1937. While at the Tykes, he appointed Tom Ratcliff, whose life he saved in 1916, as his trainer. He died at the age of 60 in 1953.

After leaving Charlton, Jimmy went on to be involved with Bristol City and Millwall, where he was still a director when he died midway through England's World Cup-winning campaign.

It was just over a month shy of 50 years after the football-obsessed young man first set foot in France during World War One.

The commanding officer of the first Footballers' Battalion, Colonel Harry Fenwick, perfectly summed up the contribution of the men he led during the Great War...