The phone rings. Shelley knows who it is before she answers it.

Embarrassed, she leaves her desk and walks into the kitchen so that none of her colleagues can hear.

“You need to come and get him. We can't control him, you have to come now,” says an all-too-familiar voice.

It's March 2017 and Shelley's eight-year-old son Cruz has been playing up at school - again.

He's only in Year 3 but his behaviour has been a problem for years.

Cruz and Shelley

Shelley first raised concerns with the school when he was in reception but as time has gone by, his refusal to play by the rules has become increasingly serious.

It is infringing on his and his classmates' ability to learn - and the school is taking action.

This time, the voice at the other end of the phone explains, his behaviour is putting himself in danger.

No more details are given about the nature of Cruz's latest misdemeanour. Shelley doesn't ask. She doesn't need to. The phone calls have become a regular occurrence, practically every other week, with other behavioural issues in between.

“He's smashed up the classroom… he's hiding under the desk... he's ripped up someone's work,” she's been told before. On one occasion, the school had to be evacuated.

This time, she is told on arrival, Cruz tried to leave the school grounds by climbing over the main gate.

Shelley apologises profusely to staff - as she has done on many occasions.

But this time feels different. She knows Cruz is running low on chances.

She has been told before that the school will consider permanent exclusion.

She needs to find a solution, but doesn't know where to turn.

It's a Monday afternoon at Hawkswood Primary Pupil Referral Unit in north London, and five children sit behind their desks, eyes on the teacher.

“Why do we think Jo was kicked out of school?” asks deputy head teacher Leah Mwaniki, in a class designed to help pupils understand how to control their behaviour.

Kyan puts his hand up. “Because she was naughty,” he says.

Kyan has been in the pupil referral unit (PRU) for more than a month, having been referred by his school.

He was at risk of exclusion because of his violent behaviour and angry outbursts.

“Do we say ‘naughty’?” Mwaniki asks rhetorically, looking for a different answer.

Teachers are careful not to label their pupils. Kyan tries again. “[She made] the wrong choices,” he says, this time getting the answer spot on.

“We teach the children that they have a choice when they feel frustrated,” explains head teacher Marie Gentles after the class.

Marie Gentles

“They have a choice when they feel anxious or angry, and we teach them they're in control of those choices.”

Hawkswood specialises in caring for children like Kyan, who have been - or are on the verge of being - permanently excluded from their mainstream school.

With small class sizes - usually with up to eight children in each - it focuses on pupils' emotional wellbeing, background and behavioural difficulties, and prepares them to go back into mainstream education.

“Some children have come from a background of some form of abuse but not all children have, and I think that's important to stress,” Gentles says.

“Most parents are working, trying really hard to provide for their children. But somewhere along the line something's gone slightly wrong.”

Like other pupil referral units across the UK, the school follows the national curriculum.

Pupils stay for at least 20 weeks before returning to mainstream education, but only once they are judged to be ready.

It is home to 40 pupils, all of primary school age, though pupil referral units catering for secondary school pupils also exist.

Such schools have become increasingly important in recent years.

The Victoria Derbyshire programme has discovered that the number of children educated in primary-age PRUs has risen 34% in recent years - from 3,181 in 2013-14 to 4,261 in 2016-17.

But there is still a stigma attached to them.

“Parents can be very, very resistant,” says Gentles.

“They think there's going to be children fighting in the corridors. And they walk in and it's really calm.”

When the idea of sending Cruz to a pupil referral unit was first mentioned to Shelley by her son's “early help team”, she admits she scoffed at the idea.

“I said, ‘No, that's where all the weird kids go, the outcasts,’” she says.

But desperate for change and worried that a permanent exclusion was imminent, she decided to contact Hawkswood herself.

“As soon as I walked through the door I thought, ‘He has to come here. This is what he needs,’” she says.

“The staff understood me. They got me. They said, ‘He's misunderstood, and we need to get to the bottom of it.’”

Shelley wipes away tears as she speaks, recalling that moment.

“The reason I'm getting emotional is because of the way they wanted to help me.

“No-one had listened. My family were giving up hope, and the school gave me that hope back.”

Throughout Cruz's childhood, Shelley's parenting had been scrutinised by her own family who thought she could manage him better.

“They would be thinking that I'm behaving like a weak parent,” she says. “They'd say, ‘He needs to be disciplined, he needs to be told. Do this with him, do that.’

“But normal discipline procedures were not working with him. It's not that I wasn't trying to be strict.”

It reached the stage where Shelley decided to quit her job to focus on Cruz, despite the financial strain it would cause.

At times, Shelley says, it was only the knowledge that she had three other well-behaved children that stopped her from questioning her judgement as a parent.

Cruz does not see his father but Shelley is keen to stress that he comes from a “very stable, loving family”, and that his father's absence is not the root cause of his behaviour.

“Cruz showed signs of this behaviour even when I was with his dad, from when he was in nursery,” she says.

Shelley with Cruz as a baby

“When he was a toddler, he showed signs of being problematic.

“He did not like to conform. He was rebellious, he had a temper. He didn't like being told what to do.”

As he grew older, Cruz would frequently cause fights with his brothers and sisters.

Cruz with his brother and sister

He was also violent in class, although it is not something he wants to talk about.

Asked to describe his behaviour at the time, Cruz pauses to reflect on how best to answer.

“I called out in class. Everybody did,” he says sheepishly, his body language closed off.

Shelley, though, knows the extent of the problem all too well - and the effects it had on her son's relationships with others.

“Cruz wasn't making friends. Any child that tried to get close, Cruz would bully, push away. They couldn't find common ground.

“Then you worry that if he's not able to make friends, not able to fit in in a class environment, how's he going to fit into the big wide world?

“I love him, but I want everyone else to love him. But how could they, with the way he's acting?”

Shelley was also concerned about the way he viewed himself.

“I remember one time when Cruz had a massive panic attack,” she says.

Cruz was just eight years old at the time.

“I didn't know how to help him. I couldn't believe it.

“Part of me was like, ‘Where's he getting this from. Has he seen a film? Is he making it up?’ But it was heartfelt. He meant it.

“He was in a really dark place, and he expressed it by not wanting to be around any more. He thought no-one loved him.

“Even though he was showered with love and care, he didn't feel it.”

As Cruz entered Hawkswood for the first time, she could only hope it would make a difference.

It's an English lesson, and four of Hawkswood's youngest pupils are sitting cross-legged on a rug in the centre of a busy, brightly coloured room.

The walls are adorned with the children's artwork, storage baskets full of cuddly toys hang from the ceiling and a rail of dressing-up clothes sits by the door.

The pupils are reading from a picture book with the teacher but one child has been separated from the group.

Anni is just five years old but she has already been permanently excluded from her mainstream school.

She is having to be held down on her chair by deputy head teacher Kate Milligan while her colleague continues reading with the others.

But Anni is pushing boundaries. She spits at Milligan's face.

Anni spits at Kate Milligan

A verbal warning is given but she continues, leading Milligan to use a restraint technique known in the school as “safe holding”.

Used as a last resort, it can take many forms. It involves a teacher applying pressure, often to the child's shoulders, to stop their movement.

In some cases it can involve the adult standing behind the child and placing their arms across them, with their right palm on the child's left shoulder, and their left palm on the child's right shoulder, effectively prohibiting them from moving.

It is designed to protect the children for their own safety and the safety of others - something that is explained to them.

Staff are regularly trained on its use.

In this instance, Milligan places her palm on the left hand side of Anni's face to stop her spitting in the teacher's direction.

“This behaviour is not acceptable and we won't be having that tomorrow,” she tells the five-year-old calmly but authoritatively.

Anni screams and continues to spit on the hand of Milligan - who calmly asks for another teacher to join her.

She arrives and sits on the opposite side of Anni, placing her palm on the right-hand-side of the child's face, ensuring she can only look forward.

As they do this, they emphasise how Anni has the choice to behave well.

“Until this afternoon, this little blip, she has been such a superstar,” says Milligan. “She had the best morning.”

Anni begins to calm down, and after just two minutes reaches the point where Milligan is confident the restraint technique is no longer needed.

“I'm taking my hand away,” she says, “because I know you can control your spitting.”

It works, and as Milligan leads her back to class, Anni holds her hand.

The restraint technique is just one of many methods teachers employ.

Another is diversion - trying to change the subject away from a child's misbehaviour - which often proves successful.

The school also finds that with all its children, improving their verbal communication skills is vital. Hawkswood employs a language therapist to help with this.

“A lot of our children here aren't able to find the words to express themselves when they first come here, which is why they do it via their behaviour,” explains head teacher Marie Gentles.

The behaviour of some of the pupils not only vastly improves while at Hawkswood, she says, but they also learn how to communicate with their peers back in mainstream school. This allows them to form and maintain friendships, often for the first time.

Another key tool is being “utterly consistent” across the board with pupils, forming “firm but fair boundaries” to help them understand what is acceptable behaviour and what merits praise and recognition.

Kate Milligan

Humour also works well, she adds. “They need to see [teachers] and understand you on a human level - and not just see you as an authority figure within the school.”

While most children attending Hawkswood have a background of violent behaviour, the school understands that they must take a bespoke approach to helping each child.

For Cruz, discipline techniques were important to keep his actions in check.

But for his long-term growth, the building of his relationship with Milligan was perhaps the key to his progression.

“I absolutely adored him,” the deputy head and Key Stage 2 teacher says. “You could tell he had an amazing mum and family.

“He's incredibly bright but the bad behaviour had overshadowed everything.”

Milligan says her biggest success in working with Cruz was creating a connection with him that allowed him to feel comfortable enough to open up.

“The children really emotionally invest with you, and so you have to reciprocate that.

“Before he was reserved in some scenarios but he came out of his shell.”

During his time at Hawkswood, Cruz told Milligan about having suicidal thoughts.

“I addressed the subject and at first he denied it,” she says.

“But then when comfortable and ready he said, ‘Nobody wants me any more.’

“We talked for hours about how important he was.

“I encouraged the three of us [Cruz, Shelley and Milligan] to talk, so he could see how desperate his mum was to help.

“It has given him ways of coping with such thoughts.”

Over time, she says, Cruz began to show his “witty, charismatic” side.

“He has a gift for art, he has a gift for sports. No-one had seen that before.

“His mum knew it was there but even she hadn't seen it for a long time.

“The other children loved him, too.”

And it wasn't just Cruz who developed with Milligan's help. Shelley did too.

At the end of the school day at Hawkswood, parents and teachers chat and even laugh together as the classes file out one by one, in perfect lines.

This easy relationship between the adults is one that is seen at school gates across the UK, but for many parents at Hawkswood, it may be an entirely new experience.

At Cruz's mainstream school, while other parents discussed their child's progress and activities in and out of class, Shelley felt unable to contribute.

“I couldn't really talk about fun, extra-curricular stuff with other parents because he wouldn't take part in any clubs or outside activities, or enjoy himself at parties.

“Because he wasn't engaging in the classroom either, I couldn't relate to any of the work that they were doing,” she says.

With Cruz not having any close friends, there was no easy route to meeting other parents.

Instead she felt alone, unable to share the realities of the daily power struggle and sleepless nights spent worrying about her son's future.

There was also another strand to the emotional problems. Shelley was ashamed.

“Why was my child the one at school that was ruining the class and misbehaving?” she remembers asking herself.

“Other people made me feel I must be doing something wrong.”

It was a feeling that intensified when Cruz's bad behaviour spiked.

“I did feel shame because there were incidents where Cruz was hitting other children at school, or maybe breaking their pencil, or ripping up some work.

“I felt that parents would be looking at me when I was taking him to school. You know, ‘That's the one. It was Cruz, Cruz did it.’

“There was once where one of the dads at school was kind of making a beeline for me, because he wanted to express how angry he was that Cruz was disrupting the class.

“And the funny thing is, I wanted to have that conversation because I wanted somebody to talk to me about it.

“I wanted to say, ‘I'm with you, I understand, if someone was doing what Cruz was doing to my kid I would feel the same’.

“But no-one ever wanted to, because no-one wanted their child to really hang out with him. So why would they need to get to know me?”

Hawkswood, in contrast, presented an outlet for Shelley.

Milligan told Shelley to come to her for advice when she was having a down day.

“I knew Shelley needed mental health support as much as Cruz,” Milligan says, reflecting on the first time she met her.

Milligan says it is common for parents to feel guilt and shame - believing they could have been a better parent.

“How on earth do you cope when no-one else likes your child?”

Now, the improvements in Cruz and Shelley's relationship since he first arrived at Hawkswood reflect Milligan's efforts and dedication.

“He is able to show me more affection,” says Shelley.

That in itself has been enough to restore Shelley's confidence as a parent.

But for many families with a child on the brink of exclusion, it is a postcode lottery as to whether a pupil referral unit is available.

Government figures show that in 2016-17 there were 6,685 reported permanent exclusions in England across primary and secondary education.

But the Institute for Public Policy Research think tank says that the real figure for pupils being educated in schools for excluded pupils - including PRUs and other provision - is far higher. In October 2017, it said that in the last year it had estimated that some 48,000 – one in every 200 pupils in England – had been placed in alternative provision.

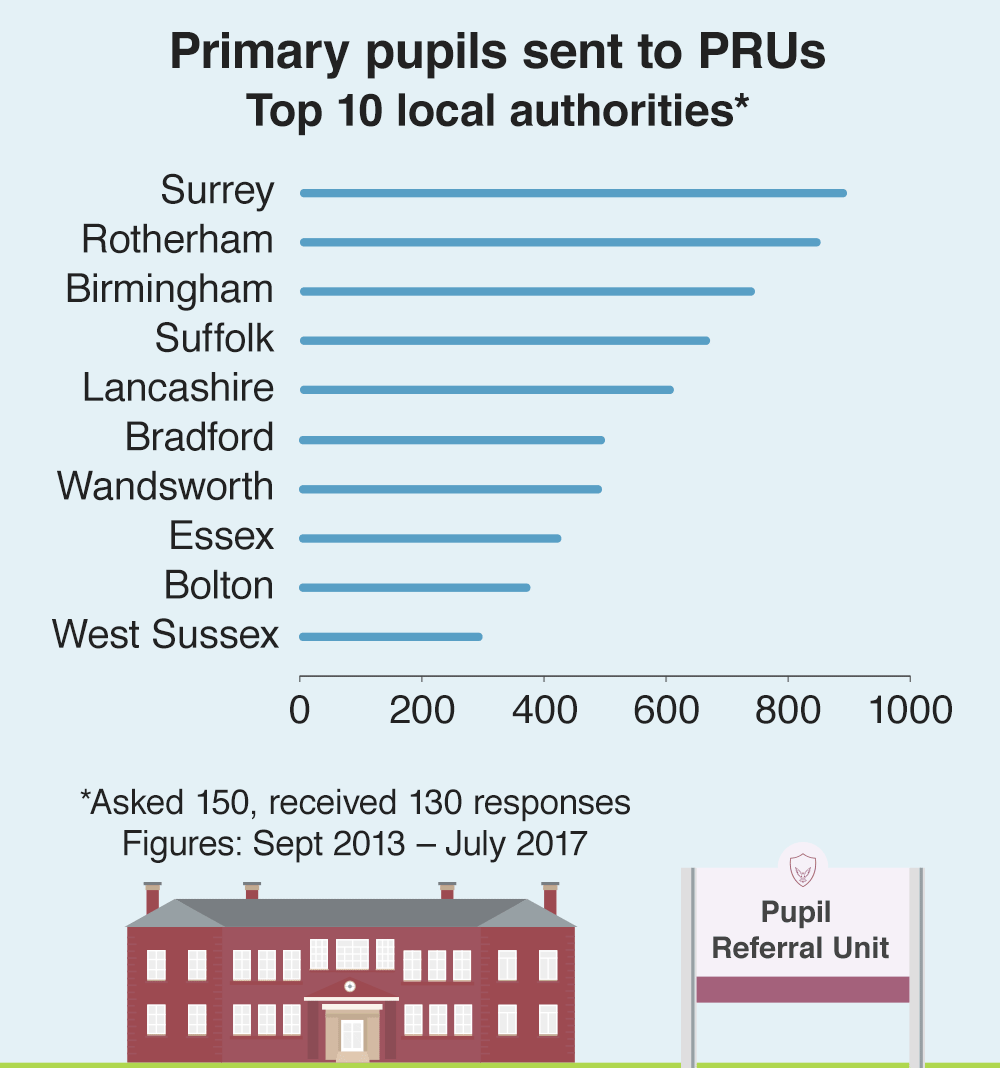

Nationwide across England, the number of primary age children educated in PRUs has risen.

The Victoria Derbyshire programme's Freedom of Information request to all 150 local authorities in England, of which 130 responded, has shown that in some areas - such as Stockport and North Yorkshire - there were no primary-age pupil referral units in 2016-17.

There are fears that in some areas, mainstream schools are referring children to PRUs simply to “get rid” of pupils causing disruption, without first exploring all avenues to managing their behaviour.

Many local areas have a fair access panel, in which head teachers and other leading educational figures decide whether a child should be placed in a PRU, or whether the school must first try other approaches.

But one man who has been running a pupil referral unit in a city in England told us in his area the panel “just fell apart, because [mainstream heads] were all a bit too parochial, looking after their own schools”.

The man - whom we will call Robert - says his PRU became vastly oversubscribed, which he says restricted its ability to work with children in small groups, as originally designed.

“They were coming out [of mainstream school to join the PRU] at a rate of just over one a day,” he explains.

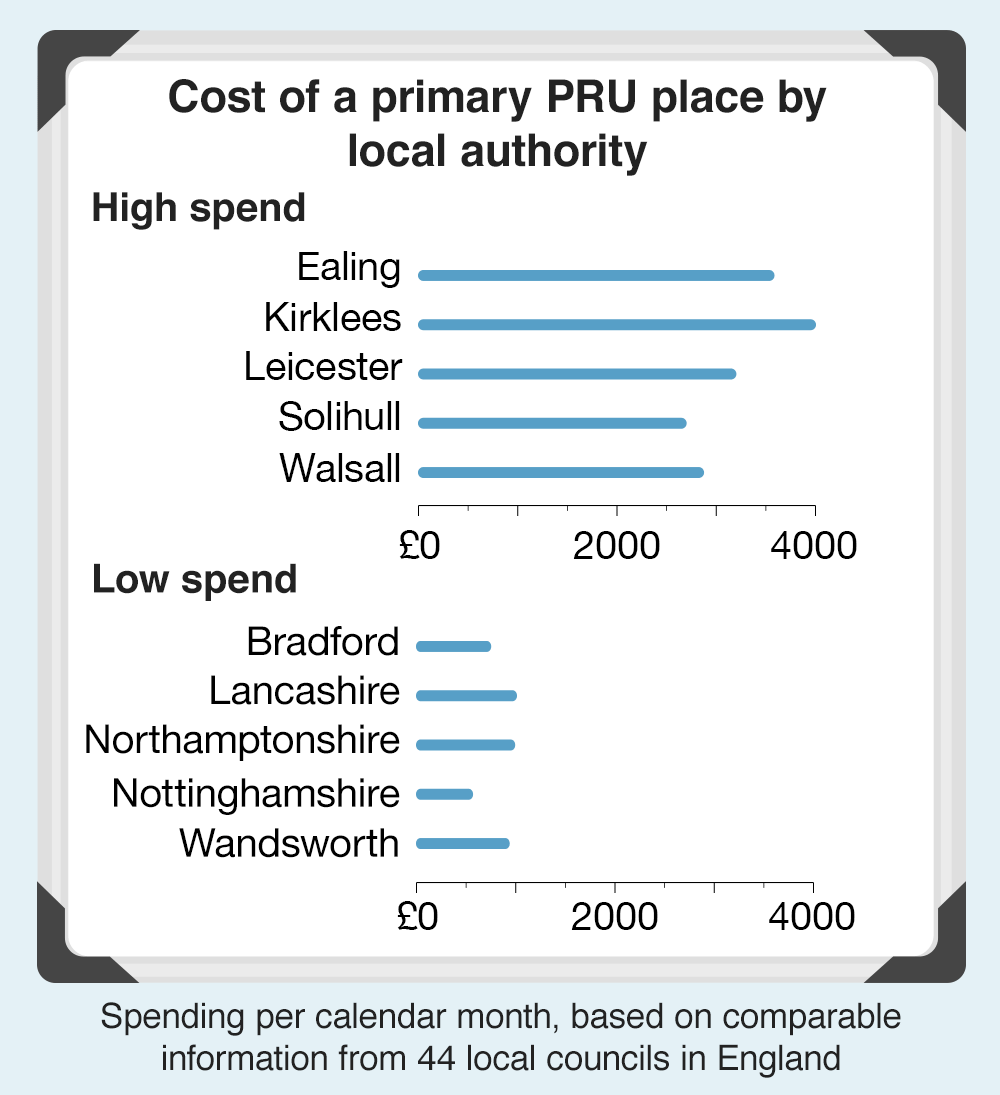

Funding for pupils also differs between local authorities - from £4,000 per pupil per month in Kirklees to £565 per month in Nottinghamshire.

In addition, £10,000 of government funding is also made available per pupil.

This total spend is far greater than the £4,900 per year the Institute for Fiscal Studies estimates is spent on the average primary school pupil in England.

But at Hawkswood - whose local authority Waltham Forest spends £1,473 each month per pupil - teachers firmly believe that giving every child an opportunity to succeed is worth the cost.

Many experts believe that early intervention is also key in preventing problems further down the line - such as in secondary school, when academic pressures mount.

For Cruz, it certainly made a difference.

Cruz stands in a gown and mortarboard clutching his scroll, smiling as he poses for the camera.

It is 20 weeks since Cruz first walked into the pupil referral unit and his behaviour has improved to the extent that he is now ready to go back into mainstream schooling.

The graduation ceremony laid on by Hawkswood is a symbol of that, showcasing the great work he has done during his time at the school.

Milligan makes a speech about the progress Cruz has made.

“It was brilliant, it was lovely,” says Shelley, remembering the sense of pride both she and her son felt that day.

She believes at the heart of Cruz's progression was his growth in self-confidence.

“They just started to believe in him. Then he started to believe in himself.

“He had never taken part in any sporting activity in his mainstream school,” she continues, giving just one example of how he has changed.

“But at Hawkswood they grabbed hold of him and said, ‘You can do it. You are a good footballer.’ Suddenly Cruz became involved in football, he started to want to be involved in sports.”

“He took part in Waltham Forest cross country, where he ran for his school in the borough. They made him believe he could do it.”

The effects of Hawkswood are still evident now in February, with Cruz having been back in mainstream school for a month.

Cruz agrees. “It was good, it was really good,” he says in a quiet, reflective manner.

Speaking in the family kitchen in between chats about his favourite Arsenal players and WWE wrestlers, his calm, happy persona is unrecognisable from how Shelley describes her son before his time at the PRU.

“I liked everything about Hawkswood,” he says, revealing how his favourite lesson was cookery class.

“We made Christmas dinner, ice cream, dinners with chicken.”

“We just 100% feel so much more positive about the future,” Shelley explains.

Cruz's behaviour is not perfect - he still has blips - but there is a marked improvement.

“He is much more able to control himself. He is able to apologise, reflect on what he's done,” says Shelley.

“He's still working hard at his behaviour but he's learned to accept responsibility.”

Milligan adds that his self-esteem is much improved. “The way he holds himself around peers has really changed. He has built his confidence, and realises, ‘I'm worth being somebody's friend,’” she says.

Shelley has not received a single phone call asking her to pick Cruz up from school since he returned to mainstream education.

She is still in regular contact with the teachers but has now learned to take a different approach to managing his behaviour.

“My attitude with the school before was, ‘I'm so sorry, sorry for his behaviour.’

“Now, I say, ‘Let's work together, let's help him.’”

Shelley also knows that Hawkswood will be there to support her and Cruz if there are any lapses in his behaviour.

“They've left the door open. So any problems for him or me, they'll get involved, which makes me feel confident,” she says.

Hawkswood Centre

Shelley hopes that by sharing her story it will improve awareness of pupil referral units and help to dispel the stigma that surrounds them.

“I definitely had a negative opinion of the children who would go to a place like that.

“But when you experience a child in your family who needs that kind of intervention, you change your whole perception of what it's all about.”

It will require continued determination but Cruz and Shelley can now look ahead with far greater optimism.

“I'm going to be an inventor,” says Cruz as he envisions his life as a grown-up.

“I'm going to make stairs so that when you fall down them you won't get hurt.”