This story contains details some readers may find distressing.

On the warm afternoon of 30 August 1980, 26-year-old Teresa Thorling had one thing on her mind - to make money to buy drugs.

Teresa was young, blonde and pretty. She wouldn’t have described herself as a prostitute but often spent Saturday nights selling sex to fund her own drug habit, and that of her boyfriend as well.

He was 20 years older and they lived together in the southern Swedish city of Malmo. It was her job to find the money for the heroin they shared.

Forty years ago, Malmo, like nearby Copenhagen, was a busy commercial hub with ferries coming in and out of the port of Limhamn on the outskirts of the city.

But unlike its famous neighbour across the Oresund - the stretch of water that separates Denmark from Sweden - it was never home to an established red-light district.

Instead, sex workers would stand in the wide, tree-lined streets of Kungsgatan and Exercisegatan, where there was space for cars to stop and deals to be struck. In the 1970s and 80s, when prostitution was still legal, these street corners attracted custom from all over southern Sweden.

It was here that Teresa headed, catching a bus from her apartment into the city centre. Later, police investigators found a bus ticket in one of her pockets stamped with the time 16.45.

Other sex workers reported seeing Teresa around Exercisegatan in the early evening. One woman saw her walking off with a client, another saw her talking to a man in a car. But no-one remembered seeing her later that night.

Two days later, on Monday afternoon, an old man collecting bottles for cash stumbled across Teresa’s body in the stairwell of a derelict building that was scheduled for demolition. She had been covered by a piece of carpet. Underneath, she was lying on her front, naked. A long, square-cut stick of wood had been forced into her rectum.

A post-mortem showed that Teresa had been killed on Saturday evening and the cause of death was most likely strangulation, though the doctor also noted high-level of narcotics in her blood. Before being killed, the young woman had been hit on the back of the head with a blunt object. She had bruising on the front of her neck that could have been caused by hands, or by a thin object being pressed against her tongue bone, which had been broken. There was no evidence that she had been raped, but there was a substance found on her back that could have been semen.

Teresa’s killing made headlines in the local newspapers, which for days ran stories about the murder in Malmo. This type of sex crime was extremely rare in Sweden and it wasn’t long before detectives in the city connected it to another murder that had taken place in Gothenburg a few weeks earlier.

Like Teresa, 31-year-old Gertie Jensen was also a drug user and part-time sex worker. And like Teresa, she had also been found stripped naked on a demolition site, her head smashed in from behind with a brick.

Malmo police made contact with the Gothenburg police to compare notes about the killings, while continuing its own investigation into Teresa’s murder, interviewing her boyfriend and the sex workers who were the last to see her alive.

There were some promising early leads. One sex worker mentioned a metallic-green Saab 900 that officers tried to trace. Another mentioned an aggressive client who used to hang around Exercisegatan and who seemed to have taken an interest in Teresa. Police found she owed money for drugs. There was speculation that a yellow Mercedes taxi that was seen near the place she was found might be involved.

But none of these inquiries led anywhere and, as the months passed, the press stopped running stories, the police moved on to other crimes and the killing of the two young women faded from view.

In August 2016, the Detective Superintendent in southern region of Sweden, Bo Lundqvist, received an intriguing email.

The subject title, in capitals, was “OP PAINTHALL”, and the sender, a detective constable from West Yorkshire Police in the north of England.

Operation Painthall, Lundqvist discovered, was a little-publicised cold-case investigation into a number of unsolved murders and assaults that may have been committed by Peter Sutcliffe, the Yorkshire Ripper. Two of these offences, said the email, had occurred in Sweden.

This was the first that Lundqvist had heard about a link between his country and the notorious British serial killer.

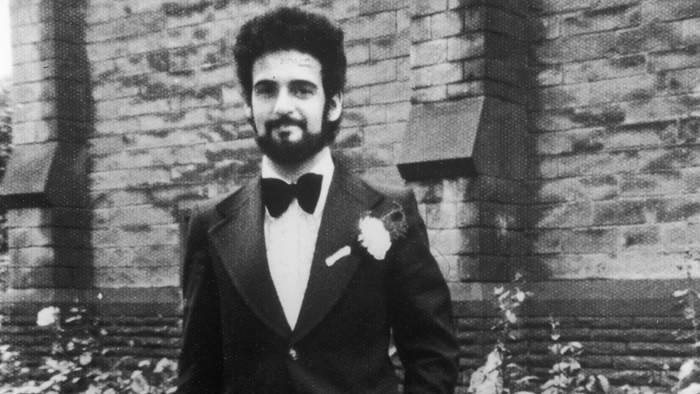

British serial killer Peter Sutcliffe, 'The Yorkshire Ripper', on his wedding day

The 53-year-old detective had studied the Yorkshire Ripper when he joined the Swedish police force in 1990, learning how the lorry driver from the city of Bradford had violently attacked women in the north of England from the mid-1970s to 1981. Sutcliffe had only been caught when officers stopped his car for using false licence plates. He was subsequently found guilty of 13 murders and seven assaults and sentenced to life in prison.

What Lundqvist didn’t know was that ever since Sutcliffe’s trial in 1981 there had been calls, both from officials and relatives, to investigate him for a number of other unsolved attacks. Now, asked the email, could Lundqvist help West Yorkshire Police with their inquiries into two murders?

His head covered with a blanket, Peter Sutcliffe, is escorted into Dewsbury Magistrates Court to be charged with murder, 6 January 1981

The email gave details of the murder of Gertie Jensen on 12 August and of Teresa Thorling on 30 August 1980.

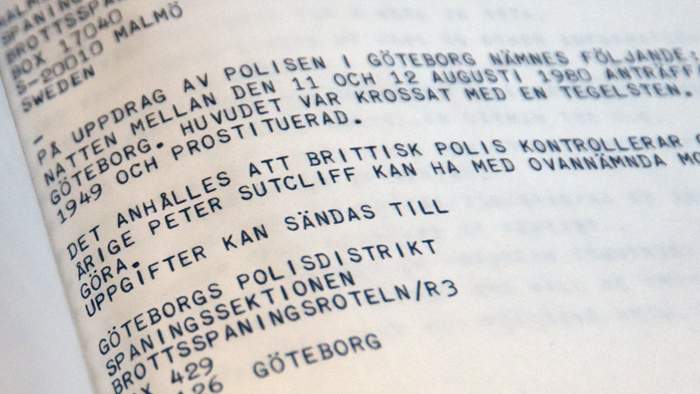

It went on to explain that the West Yorkshire Police had found a telex which had been sent to its office by the international crime organisation, Interpol, in the 1980s.

This indicated that Sutcliffe may have travelled with a lorry on board a car ferry between the port of Limhawn (which Lundqvist understood to be a mis-spelling of Limhamn) in Sweden and Dradoer (a mis-spelling of Dragor) in Denmark. The email then quoted two dates: 30 August 1980 and 1 September 1980 – coinciding with the date Teresa was killed.

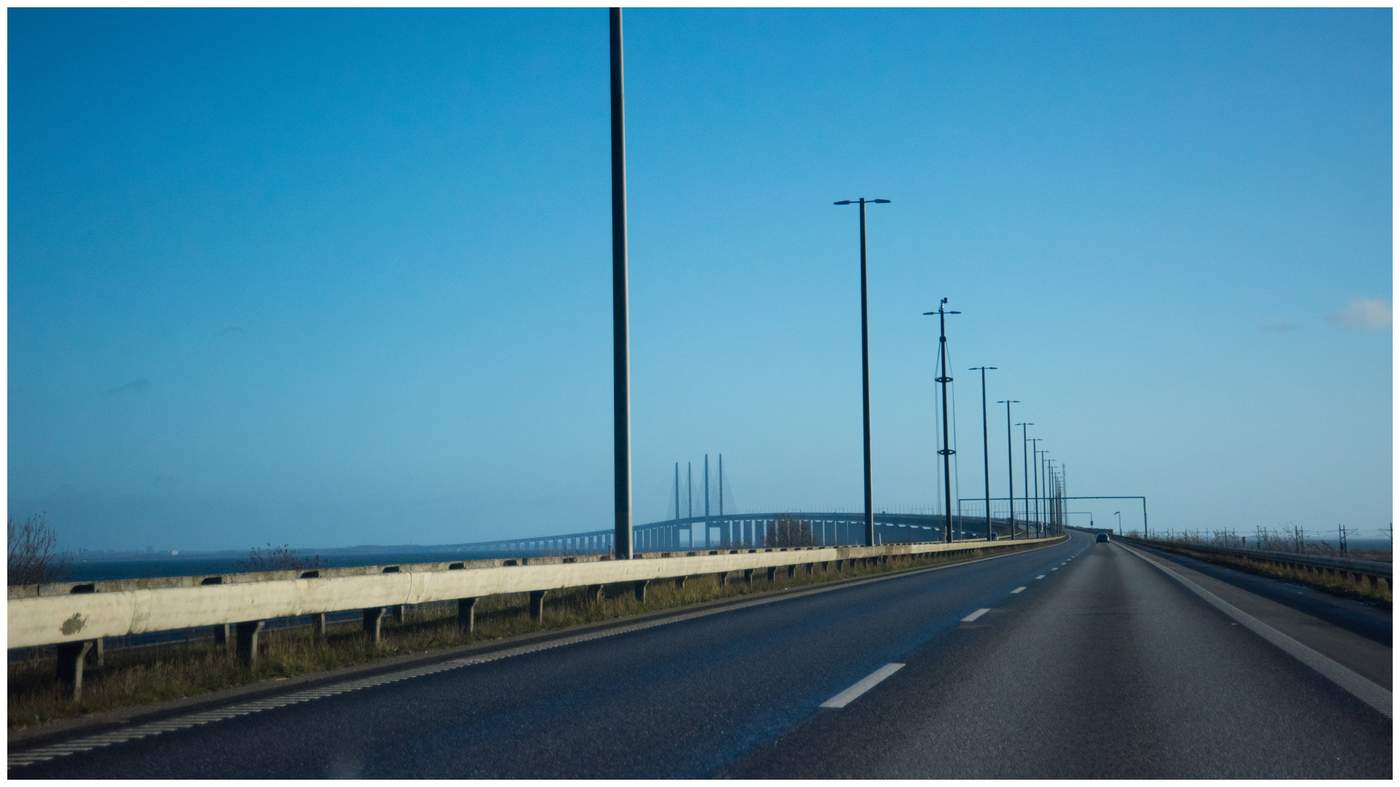

Back in the 1980s, this one-hour ferry journey across the waters of the Oresund was a busy route with dozens of crossings a day. Now the ships have been replaced by the Oresund Bridge - made famous by the Scandinavian detective drama, The Bridge, for which, coincidentally, Lundqvist acts as a consultant.

“The only thing that tops fiction is real life,” he says, comparing the scripts he checks for accuracy with real homicide cases.

“I see it every day, every year, year in, year out.”

Here, he thought, was another example of how the truth could be more astonishing than fiction. Why was this the first he had heard of these two brutal murders and why had they not been solved?

The murder of Gertie Jensen fell outside his jurisdiction, but Teresa Thorling had been killed in his city.

“We haven't investigated cold cases for very long - less than 10 years. But they are so important in society,” he says.

If we don’t stand up for people who've been killed, who will?”

The email from West Yorkshire Police concluded with a series of questions. Was there still paperwork? Had Peter Sutcliffe ever been considered a suspect? Had there been a cold case review and was there any forensic evidence that could be tested?

Lundqvist found he could answer yes to all of the questions. There was paperwork, Peter Sutcliffe had been named, there had been a cold case review in 2005 and there was forensic evidence - most notably a hair that he described as being found in such a way that would make it very interesting to test for DNA.

Ideally, the detective would test this evidence himself, but he faced a problem. Swedish law has a statute of limitations, which stipulates that any unsolved crimes that took place before 1 July 1985 can no longer be investigated. Lundqvist was legally barred from re-opening the case.

Now, reading through the email, he felt a glimmer of hope. Perhaps the British police could help find a way back into it? Perhaps they could test for DNA?

And then there was the bigger question. Could it be that the British serial killer was actually responsible for the deaths? And if not, who was and could Lundqvist catch him?

We must show that if you kill a person, we will never stop coming after you. Never,” he says.

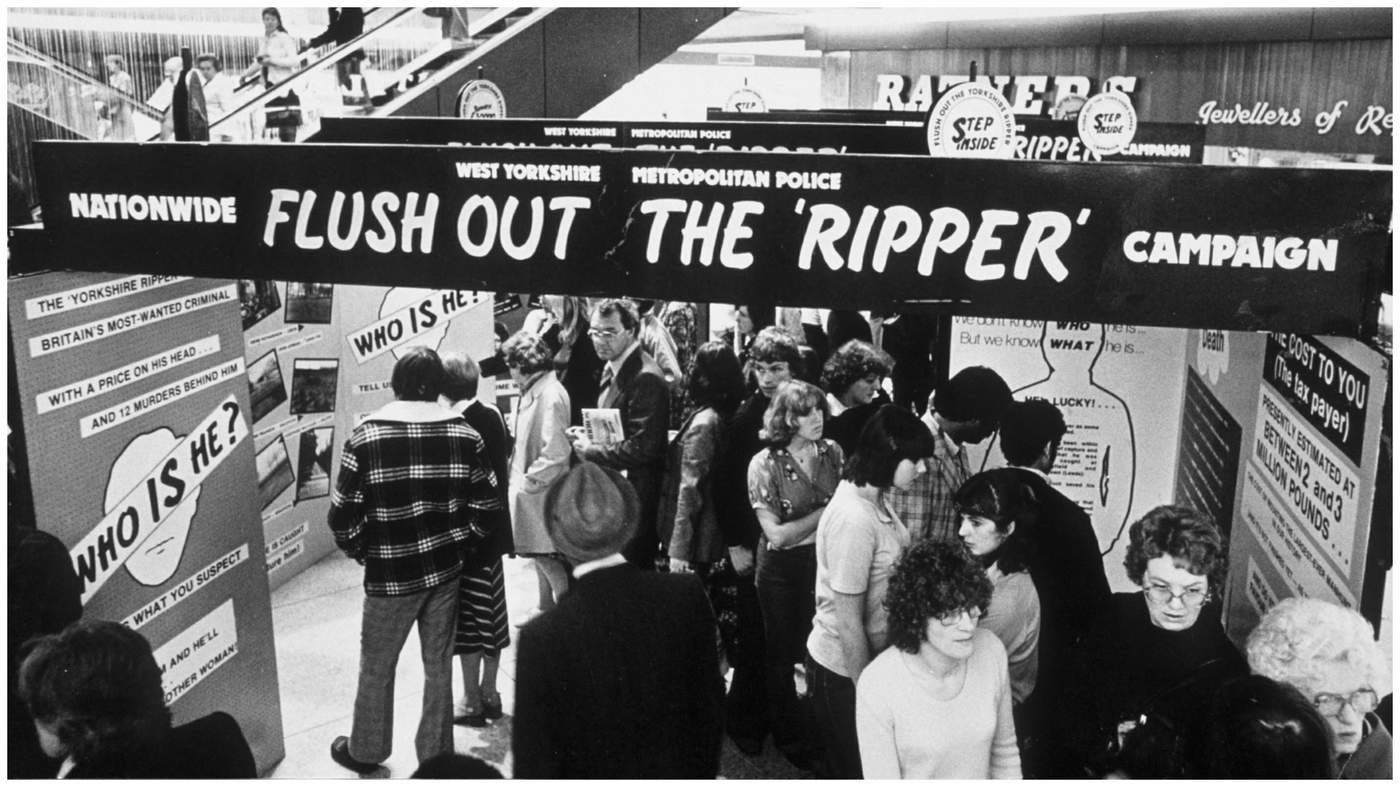

In the late 1970s, stumped by their inability to catch the killer, police in West Yorkshire were seriously considering the idea that, in between attacks in England, the Yorkshire Ripper was working or travelling abroad.

Joan Smith, who covered the murders as a reporter, remembers this theory. In 1979, as part of the Sunday Times’s investigative Insight team, Smith lodged a Freedom of Information request with the FBI in the US to ask if they had been briefed by the British police about the Ripper killings.

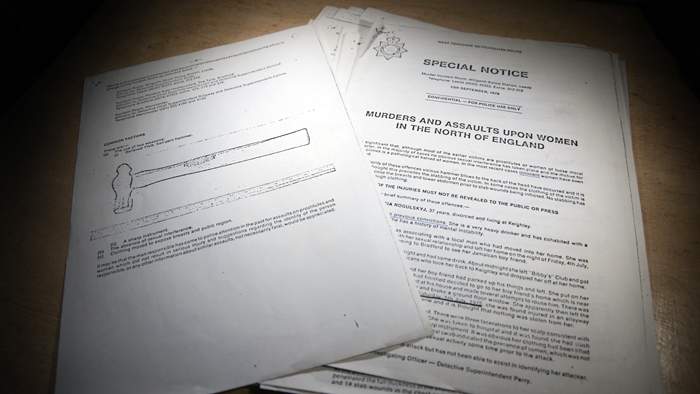

A year later, a brown envelope from the FBI arrived at the Sunday Times office in London. In it was a dossier compiled by West Yorkshire Police which they had sent to police forces around the world. It detailed the attacks and asked if other countries had recorded anything similar.

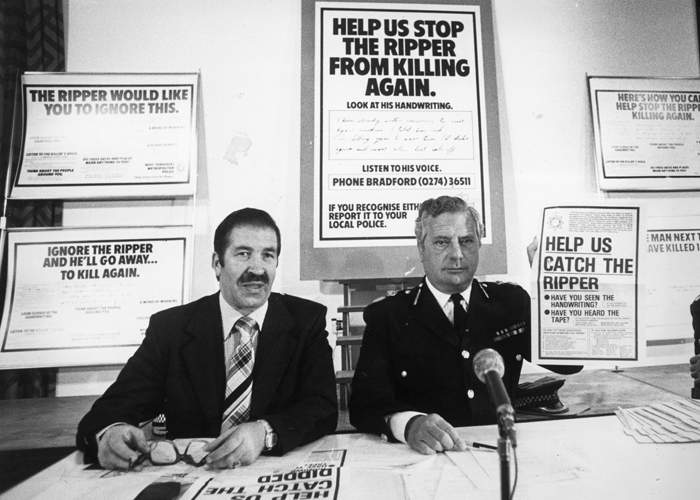

West Yorkshire Chief Constable Ronald Gregory (right), who led the investigation and Detective Chief Superintendent Jim Hobson, appeal to the public for help

At the time, Smith used this information to expose what she regarded as an incompetent and sexist police investigation - one that failed to take the murder of women, especially sex workers, seriously.

“The police would say, the day we have him sitting across the table, we will know it's him,” she says.

“And I was thinking: ‘How will you know? Because you make awful jokes about women as well.’

This was a kind of macho culture where contempt for women was pretty normal.”

Smith remembers an occasion when she entered a press conference just as a group of prostitutes, who had been brought in to discuss the danger they were in with the police, were leaving the room.

“One of the reporters shouted to the cops, ‘I hope we’re not going to catch anything sitting on these chairs,’” she says.

“And the cop said, ‘Well, I kept well out of their way just in case.’ And then the press conference started and the atmosphere switched and suddenly it was all, ‘We take this very seriously, we care about every woman.’”

Asst Chief Constable George Oldfield holds a Press Conference in November 1980

The police were working on the assumption that the Ripper was killing out of a hatred of prostitutes. The dossier made it clear that the police thought the victims who weren’t sex workers had probably made themselves targets because of their behaviour - by going out late at night, by drinking alone, or by dating Jamaican men.

The theory led the police to overlook a number of victims who didn’t fit this pattern - like the 14-year-old school girl, Tracy Browne, whose attack by a man wielding a hammer was later admitted to by Sutcliffe from jail. Browne had given an accurate photofit description of Sutcliffe to the police, but this was ignored at the time because she didn’t fit their victim profile.

As more and more victims were killed, the West Yorkshire investigation came under increasing criticism. Even the Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, is reported to have been so frustrated with its ineptitude that she threatened to go up to Yorkshire and take control herself.

Joan Smith's copy of the dossier compiled by West Yorkshire Police

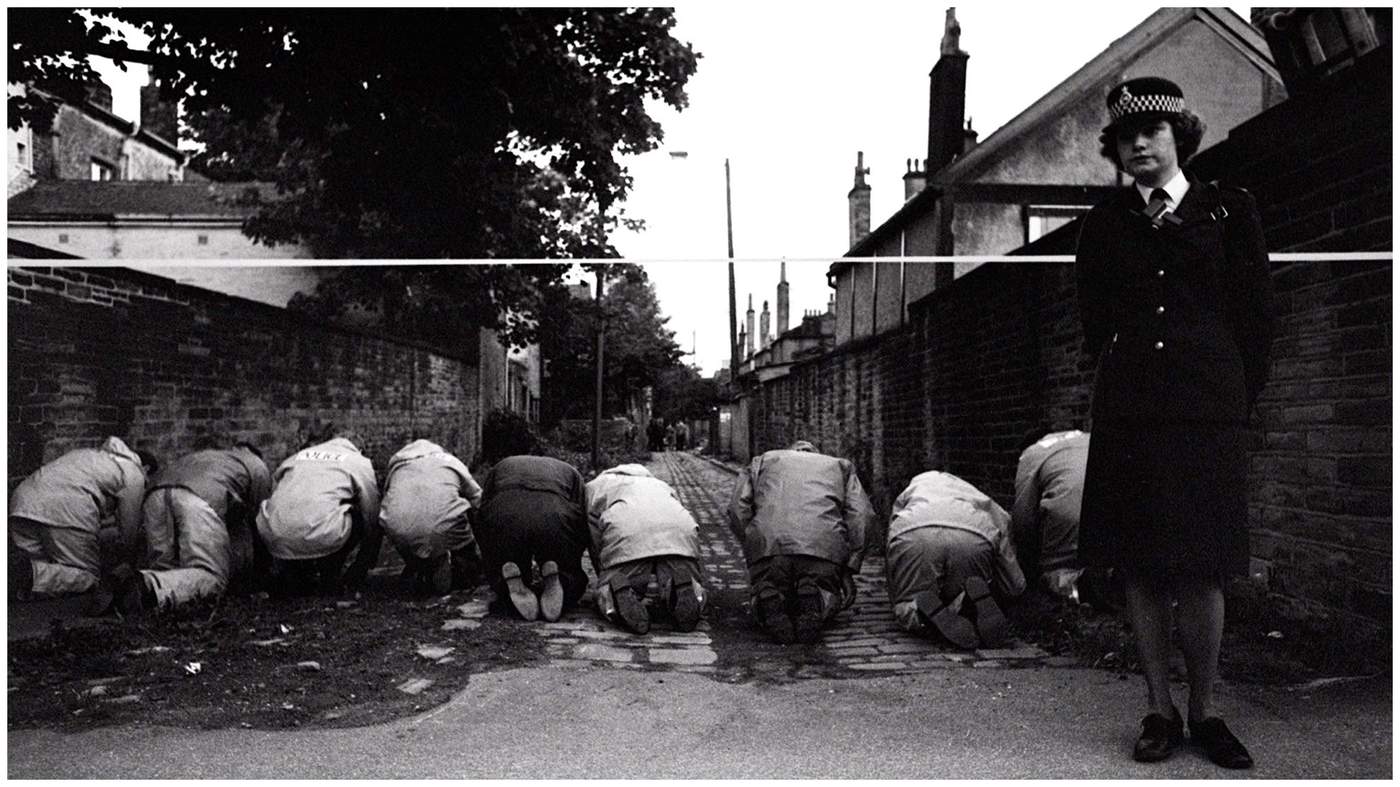

After Sutcliffe’s trial, two inquiries were set up to examine police failings - the government-commissioned Byford inquiry and the internal police Sampson inquiry. They both made sweeping recommendations for change, with the Byford inquiry identifying a further potential 13 surviving Ripper victims.

Retired police officer Chris Clark believes that as well as these 13 survivors, Pete Sutcliffe killed another 23 women and one man, and attacked, but didn’t kill, another man.

He believes some of these attacks are under investigation by Operation Painthall, though West Yorkshire Police have said little about their operation.

In an email to the BBC, they would only confirm that the operation was an ongoing process.

“There's been cover-up after cover-up and survivors have no closure,” says Clark, who has spent the past five years investigating the attacks and wants West Yorkshire Police to make a public statement about their findings.

Joan Smith, who now advises the Mayor of London on strategies to combat violence against women, also believes the police have a moral duty to publicise the results of their inquiry.

“Cold cases are so important because people have to live with a terrible lack of knowledge about their lost relatives,” she says.

The original investigation was so utterly incompetent and women were so let down by it, that I think it’s really important to establish the truth.”

At the same time as Smith was reporting on the Yorkshire Ripper in Britain, Goran Svedberg was working as a crime reporter in Malmo for the local newspaper, Kvallsposten.

In the early 1980s, Svedberg remembers an equally cosy relationship between Malmo’s crime reporters and the police as Smith described in Britain. At that time, journalists were allowed to wander through the police headquarters as they wished. The detectives and reporters were all men, they were friends and they spoke freely about cases.

Svedberg was there when news came in that Teresa Thorling’s body had been found in a derelict house. He says her murder made headlines for a few days but was soon dropped. Although this type of killing was rare, it wasn’t a surprise that it happened to a girl like Teresa.

“It was a big thing, but not a major thing because she was a drug addict and prostitute,” he says.

But a few months later in January 1981, Sutcliffe’s arrest sparked a renewed interest in the case.

Reporters noted similarities between Teresa’s murder and the Ripper killings. Like many of his victims, she had been stripped of her clothes and hit on the back of the head, although Sutcliffe often used a distinctive ball-peen hammer and this hadn't been used here. But he was also known to strangle his victims using a knotted-rope, the kind of implement that matched Teresa Thorling’s strangulation injuries.

On 12 January, the Malmo police sent a telex to Interpol to ask the British police to confirm whether Sutcliffe had ever travelled to Sweden, citing press reports placing him on the ferry between Dragor and Limhamn at the same time that Teresa was killed. It was the telex that is referred to in the email sent by Operation Painthall.

It’s difficult to pinpoint exactly where the rumours that Sutcliffe was in Sweden originated.

The Malmo police telex says they came from the press. But there were no local newspaper reports mentioning the possibility of Sutcliffe being in Sweden, before 12 January.

It’s only on that date, and a few days afterwards, that there are a handful of articles referring to a possible link between the lorry driver and the Swedish murders. One mentions the police telex and another speculates that Sutcliffe had an accomplice who worked for the same transport company and travelled to the continent on business.

Svedberg thinks he has the answer.

In January 1981, he learnt that a British journalist living in Malmo, Roy S Carson, was planning to write a piece for the British newspaper, the Daily Star, linking Teresa’s murder with the recently arrested Peter Sutcliffe.

“Roy said the British police were interested in the case and he wanted to know more about it,” says Svedberg.

“Roy was an extremely creative journalist so maybe this was true, or maybe he made it up.”

Later that day, Svedberg found out that the Daily Star was planning to buy photos of Teresa from his news desk. At the time, Svedberg was freelancing as a correspondent for The Sun newspaper in the UK, which was a competitor to the Daily Star. This spurred him to ring his Sun bosses in London and offer them an article on the same story.

“I told them it was nothing, I didn’t believe in the story,” he says.

“But they asked me if I could still do something saying it wasn't true.”

The next day, according to Svedberg, The Sun ran his story, but the Daily Star decided not to run Carson’s piece. The Sun expose sparked even more press interest. Svedberg remembers reporters from London calling the police in Malmo. Even the correspondent for the International Herald Tribune rang from his European base in Paris.

It is impossible to verify this story with Carson, who has since died. Curiously, The Sun’s archive in the months following January 1981 does not reveal any articles about the Swedish murders. There is no mention in any of the British papers of the police investigating a link between the Swedish murders and the Yorkshire Ripper.

Two weeks after the Malmo police sent their telex to Interpol they received a reply from West Yorkshire Police in Britain. Sutcliffe had not been in Sweden - the only time he had travelled abroad was to visit his wife’s relatives in Czechoslovakia in 1971 and to go on honeymoon to Paris in 1974.

That was the end of the matter - until Lundqvist was contacted by Operational Painthall.

For months after he replied to Operation Painthall’s email, Lundqvist heard nothing back from the British detectives.

Then in May 2017, the Swedish newspaper Kvallsposten published a story on Operation Painthall’s inquiry.

A few days later, Lundqvist received a reply - this time from the man leading the cold case review, Detective Chief Inspector James Dunkerley.

DCI Dunkerley wrote that it was absolutely certain that Sutcliffe had never been in Sweden.The telex that Operation Painthall had originally written about described nothing more than a rumour. As far as he was concerned, the case was closed.

Except that for Lundqvist, the journey had just started. If it hadn’t been for Operation Painthall, he wouldn’t have known about the unsolved murders of Teresa Thorling and Gertie Jensen. Now he did, he was determined to see the investigation through to the end.

His next hurdle was negotiating the Swedish statute of limitations.

Until recently, Swedish law had ruled that any crime committed more than 25 years ago was barred from being prosecuted. In 2010, the Swedish parliament changed the cut-off date for prosecutions to 1 July 1985. Lundqvist suspects this date was chosen to make sure the still-unsolved murder of the Swedish Prime Minister, Olof Palme, in 1986 would never fall beyond the statute.

“In a matter of years, this date won’t matter anymore because all those involved in the crimes will have passed on,” he says.

“But for now we should only care whether we can prosecute or not. Modern techniques to solve old crimes are so much better, and they’ll keep improving, so the statute shouldn’t stop us looking for justice.”

To get past the statute, Lundqvist has turned to criminal psychiatrists and profilers to help build a case for testing the forensic evidence saved from the 1980s murders.

“We're now of the opinion that the Gothenburg and Malmo murders were carried out by the same perpetrator,” he says.

This is significant, he says, because if the perpetrator killed twice, it is likely he went on to kill again and it’s possible that one of these crimes occurred after the 1985 cut-off date for prosecution.

Lundqvist has used this argument to justify testing the hair found on Teresa’s body for DNA. In December, he sent the evidence from her murder to the Swedish National Forensics Laboratory in Linköping.

He expects the results anytime soon.

“It’s important to speak for the dead, whether they are a prostitute or whether they have a profession of any sort,” he says.

“And it’s very, very important to solve homicides. It has a calming effect.

“The more [killings] that are done, and the fewer we solve, the more there will be."