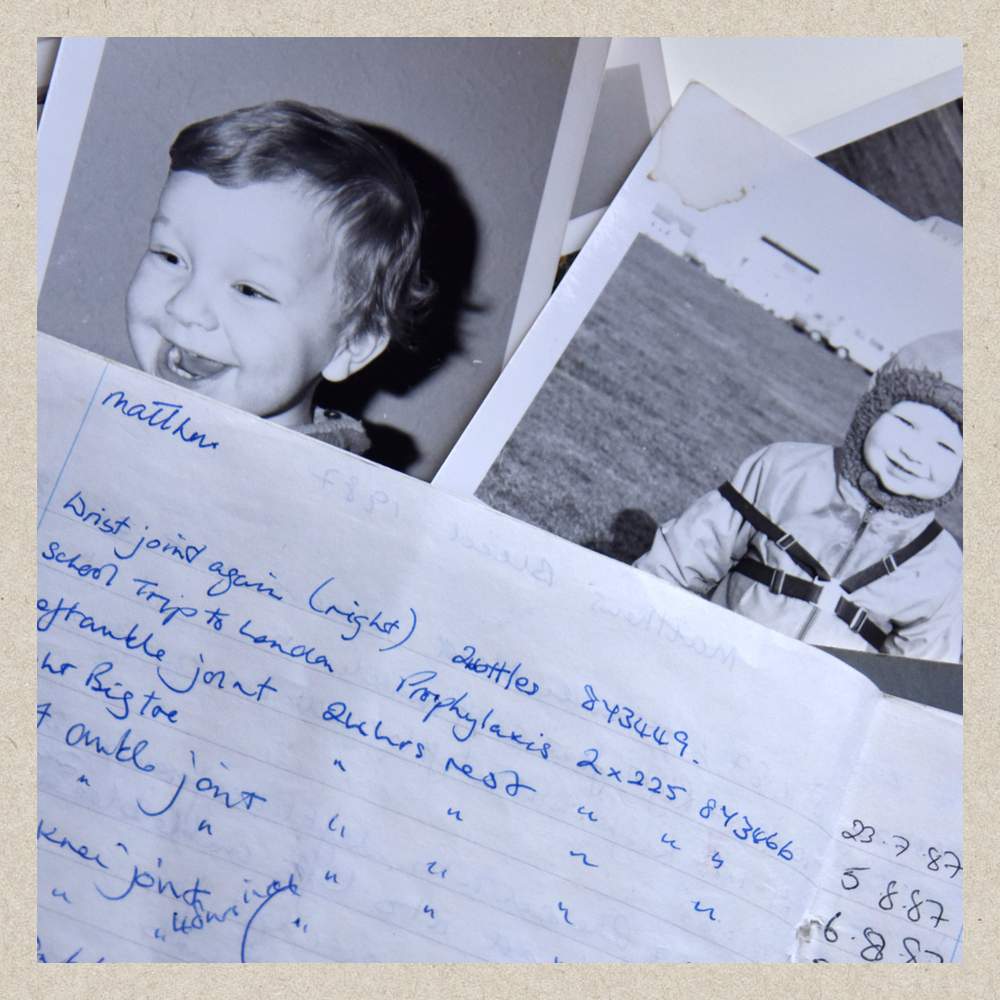

Matt Merry can’t recall the exact words his mother used to tell him he was HIV-positive. He just remembers not knowing how to react, not at first, not in front of his mum. She had sat him down at a table in the back room of their home in Rugby to break the news. Matt was 12 years old.

He’d had the virus for four years, his mum explained. An injection he’d received to treat haemophilia, the bleeding disorder he was affected by, had been contaminated with it. This was 1986, at the height of the Aids epidemic, and an HIV diagnosis was perceived as a death sentence.

After the first signs of infection started to show, he would probably have two years to live, the doctors told his parents.

That night, as Matt lay in bed with the lights out, the numbness he'd felt all day began to ebb away. The enormity of what he'd learned finally started to dawn on him. All he knew of HIV and Aids was TV footage of skeletal-looking young men, their bodies covered in sores, wasting away in hospital wards, and he started to cry.

“From that point onwards, for the rest of my teenage years, I had this stopwatch hanging over my head - and at any minute someone could push that button and start this two-year countdown until I waste away and die,” he says.

There was something else Matt’s mum had said to him, too - he wasn't to tell anyone. Not friends, not teachers, initially not even his younger brother. The next time he went to school he was carrying a secret that he couldn't share.

In 1986, HIV and Aids were the subjects of an all-pervasive, visceral fear. In the media, the disease was largely associated with groups such as drug users and gay men, who were routinely stigmatised at the time.

Matt had heard of homes that were daubed with graffiti - “AIDS SCUM” and so on – when a rumour spread that someone living there had the condition. The panic only intensified the following year, when the government released its infamous “tombstone” adverts, which depicted Aids as an ominous, deadly presence.

Looking back, Matt thinks his parents made the right decision about keeping quiet. “It wasn’t really an option to let anyone know,” he says. Sometimes other pupils gave him stick about being a haemophiliac, and he can't imagine what would have happened if news of his HIV diagnosis had got out. It had emerged that thousands had been infected with HIV through contaminated blood products, and Matt had heard of schools where parents had pulled out their children on learning that there was a haemophiliac in the class.

But the burden of secrecy weighed heavily on him. “It’s so lonely going through that and experiencing that on your own - not being able to talk to anyone about it, not being able to discuss it.”

He was never offered any professional support or counselling. There were no psychologists or therapists to help him cope.

“I guess I could have talked to my mum or dad or brother - but it’s almost like it was so upsetting at the time that I didn’t want to talk about it, because I knew I’d just break down in tears, so I just shut it away and got on with it.”

To his friends and classmates, everything seemed normal. No-one knew what was going through his head. To him, it seemed a certainty that he’d be dead by the time he was 20. He could never have a girlfriend, let alone marry or have children.

His family had nurtured ambitions for him - his dad was an engineer at the Rolls Royce plant in nearby Coventry, and both parents wanted their son to do well at school and go to university. But after he learned he was HIV-positive - he would later find out that he had been infected with hepatitis C too - Matt stopped trying at school. What was the point?

“Why spend all that time revising and doing homework when I’m not actually going to have a career or anything?” he reasoned.

Without realising it, Matt had been caught up in what's been called the biggest scandal in NHS history - one that has resulted in the deaths of at least 2,883 haemophiliacs in the UK, according to campaigners. It's feared that tens of thousands of non-haemophiliacs could have been infected via blood transfusions, too.

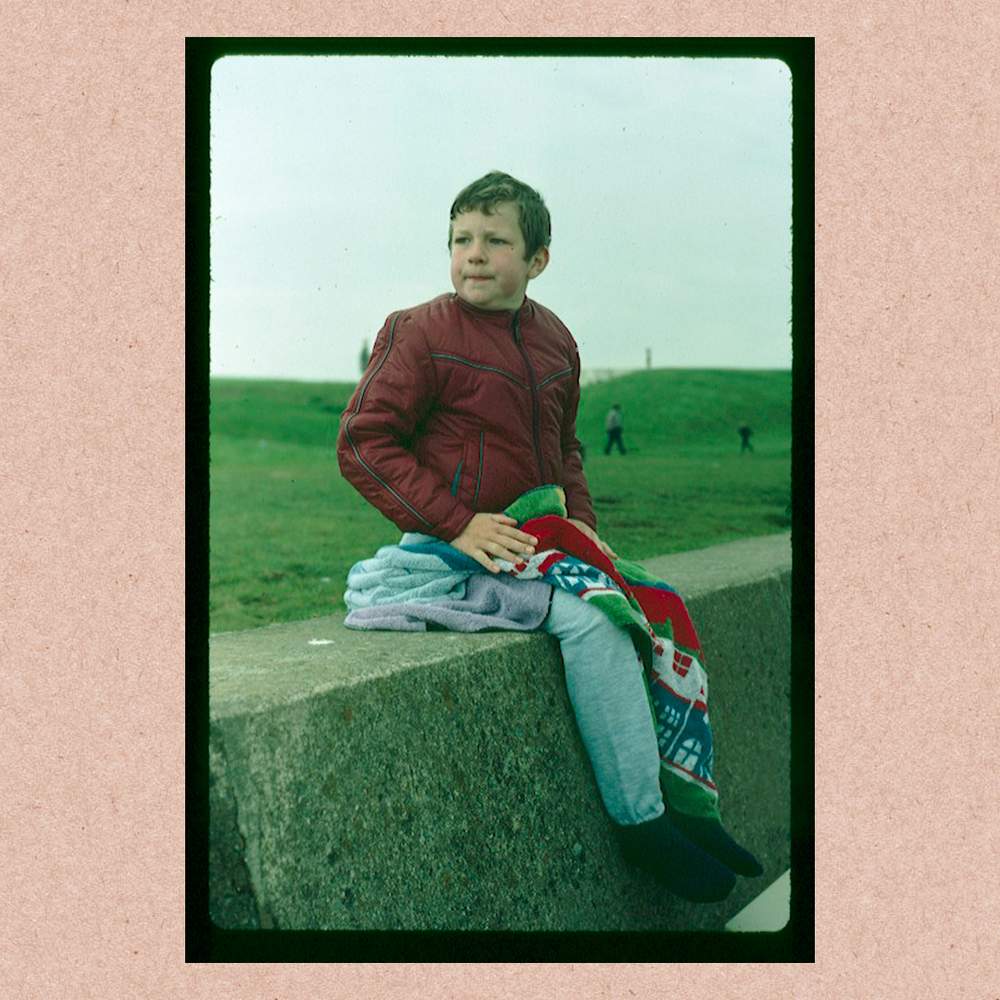

He’d been diagnosed as a toddler with severe haemophilia, meaning his blood was slow to clot and he would bleed for longer than other children. This, in turn, meant Matt would bruise easily and cuts would take longer to repair. Bleeds could be extremely painful and restricted his mobility - blood would fill the cavities of his joints, which made moving them all but impossible. His parents wouldn’t let him climb trees or have a BMX bicycle.

Haemophilia also meant Matt could never achieve his ambition of becoming a pilot with the RAF.

But during the 1970s and 80s, a new treatment for haemophiliacs became available. Injections of proteins called factor concentrates - usually Factor VIII, as in Matt’s case - helped clot their blood. It was made from donated blood plasma, and there was so much demand for it that the NHS began importing it from abroad, notably the US.

Now, instead of going into hospital every time he bled, Matt had a supply of Factor VIII at home - at first, his mum would inject him, and then he learned to do it himself. He’d go on summer camps in North Wales with other young haemophiliacs, accompanied by doctors equipped with supplies of Factor VIII, and the boys could play outdoors safe in the knowledge that they’d be treated if they fell and injured themselves.

But unknown to Matt and his family, much of the imported American Factor VIII was made using blood plasma donated by prison inmates and drug addicts, who were high-risk groups for viruses like HIV and hepatitis C. In many cases they had been paid for it. And because the factor products were made in huge vats from the plasma of tens of thousands of people, if just one donation was infected that would be enough to contaminate the whole batch.

Warnings about imported Factor VIII had been raised as early as 1974, and the government said it would make the UK self-sufficient in factor concentrates within three years – but it didn’t. As the Aids crisis unfolded in the 1980s, the Department of Health was warned again in writing that US blood products should be withdrawn, but it wasn’t until 1986 - 12 years after concerns were first raised - that this was advice was finally heeded.

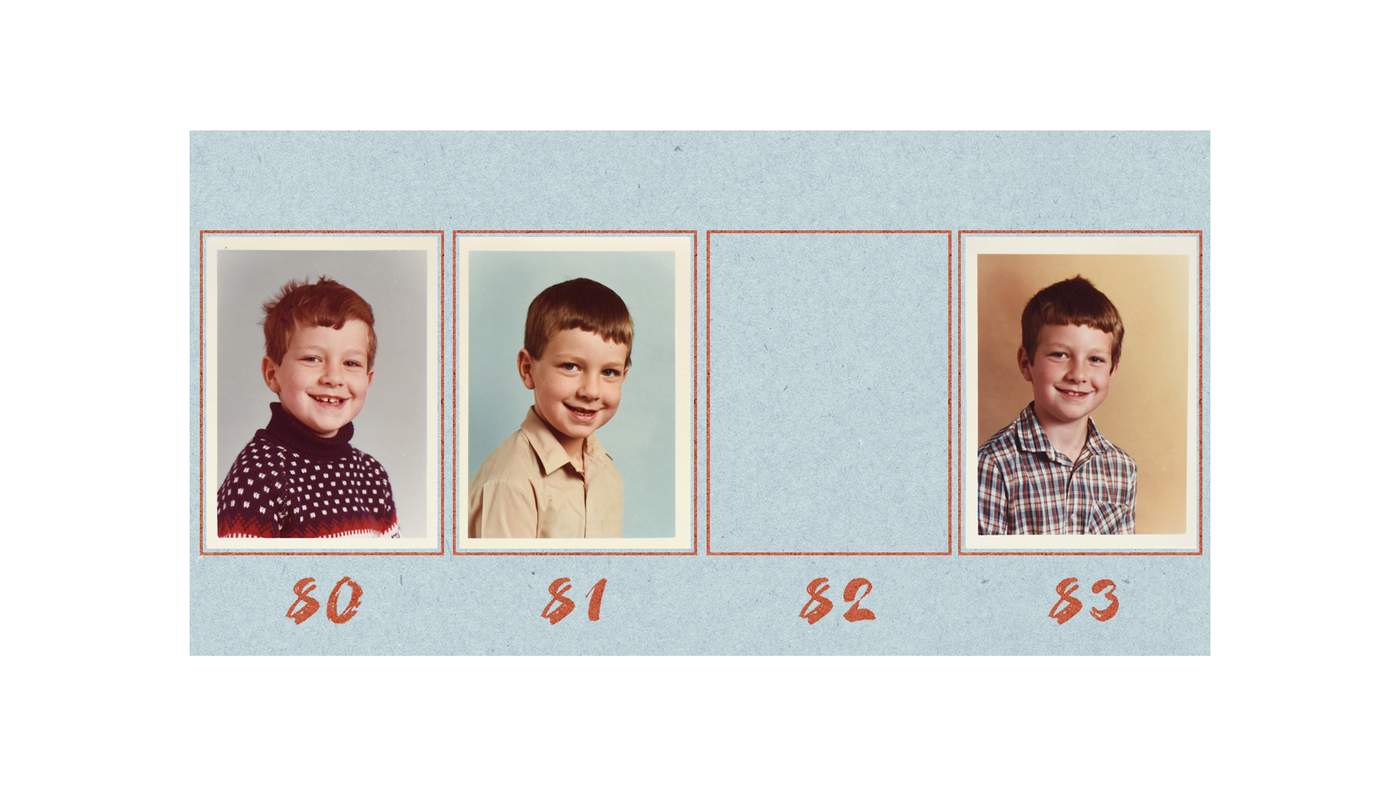

When Matt’s mother was told that her son had been infected with HIV, she hadn't even realised he’d been tested for it. She’d fastidiously kept records of the batch numbers of the Factor VIII he’d been given, though. She looked back through them to 1982, when he’d been given a series of injections of proteins produced by an American company. She didn't have any school photos of him taken that year because the photographer came on one of the many days when he was ill.

At school, Matt had a tight circle of close friends, but none of them knew why his grades were plummeting. He did the bare minimum for his GCSEs, scraping through with five passes. He put even less effort into his A-levels: “I just spent the two years mucking around, having fun with my mates.” In the end, he had one E grade to show for it. But despite the dire predictions that he would die within two years, Matt still appeared to be healthy, apart from his haemophilia.

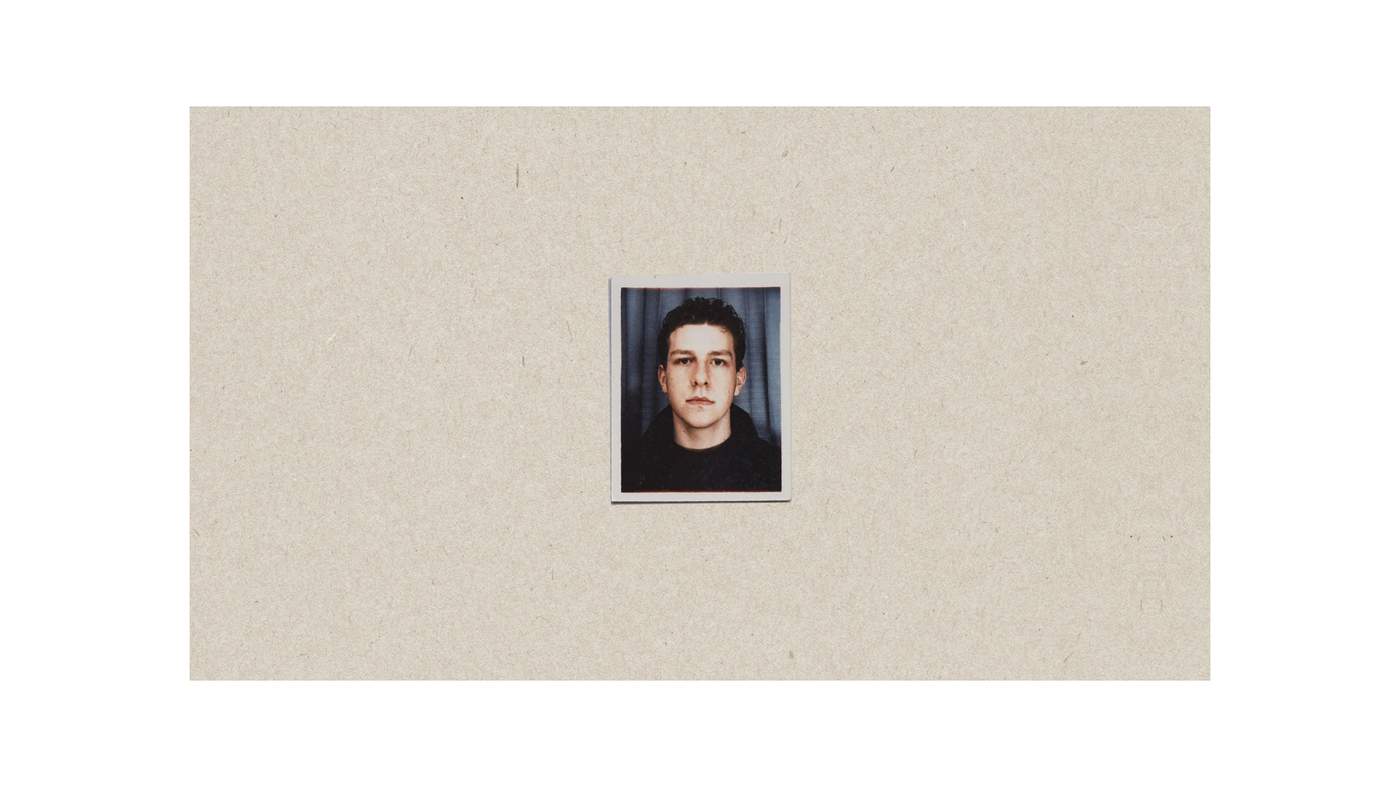

On 19 April 1990, just after Matt turned 16, he was assessed by a psychiatrist at Great Ormond Street Hospital. “He believes there is a 50/50 chance he will develop Aids,” the doctor wrote in his report. “He tries not to think about the future and when he does feel upset he tries to distract himself.” Matt, the report continued, had a “strong psychological defence system” but this was “easily penetrated at which point he becomes clearly distressed”.

It was likely that even if he did not develop Aids in the next few years, Matt would “suffer major emotional difficulties”, the psychiatrist said. “It will be difficult for him to make satisfactory relationships with people of the opposite sex, because of the very real danger of cross-infection,” he went on. “He is already worried about this and distressed at the fact that he will not be able to have children.” It was to his parents’ credit, the report concluded, that he was coping so well.

Around this time, Matt began smoking cannabis. “I just thought I’d give it a go - you know, what harm’s it going to do? The damage has already been done.” From there he moved on to speed and ecstasy. It was now the early 1990s, and Matt threw himself into the rave scene. He’d stay up all night, off his face, and then “come back home to mum and dad the next morning, eyeballs as wide as saucers, and go to bed for the rest of the day”.

His parents didn’t realise what was going on at first. Then one day he came home from college and his dad pulled out a stash box filled with speed and cannabis. They’d found it in Matt's bedroom. “What’s this?” his dad asked. His mum was in tears. Matt felt like the floor had fallen out of the room. His parents wanted to know why he’d been taking drugs.

“I said: ‘Well, why not? You know, I might not have long to live. I want to try and enjoy and experience as much as I can before I die.’” It wasn’t an easy point to argue with.

One night, when he was 17 or 18, Matt had been out drinking in town. He was walking home with a friend when something compelled him, for the first time ever, to tell someone outside his immediate family that he had HIV.

The friend was shocked, but he was understanding. “It was a case of: ‘Well, OK, it is what it is, but you’re still my mate.’” They walked past the friend’s house, and then past Matt’s house, and they carried on walking and talking it over until three in the morning.

The relief washed over Matt. Over the next three or four years he began telling his closest friends, individually. As time went on it became easier - he never had a negative reaction from any of them. “What does it mean?” they’d ask. “How are you? Are you going to be all right?” But on each occasion, he anxiously weighed up whether or not he could risk sharing his secret. “I always very carefully considered who I told,” he says. It was always a case of: “Can I trust this person?”

After school, Matt signed up at a further education college in Leamington Spa. He didn't see much point getting a job, and it was another excuse to muck about for a while. He spent two years there not turning up to lectures very much, and left with no qualifications to show for it.

Now he was 20. Many of his friends were at university in Birmingham, so he moved there, signed on and concentrated on partying. But he sensed that he was being left behind. His friends were moving on with their lives, earning degrees, getting together with girlfriends, and Matt wasn’t.

There wasn't one single moment when it dawned on him, but slowly, over time, he began thinking:

I’ve had this since I was eight years old, and I was always told I’d have two years to live.

"Well, what if it’s not two years? What if it’s longer?"

It had never occurred to him that he might reach 40, let alone 50 or 60. But if his health continued to hold out he was destined for a dead-end job. He realised he had to do something in case he was still alive in 10 years’ time.

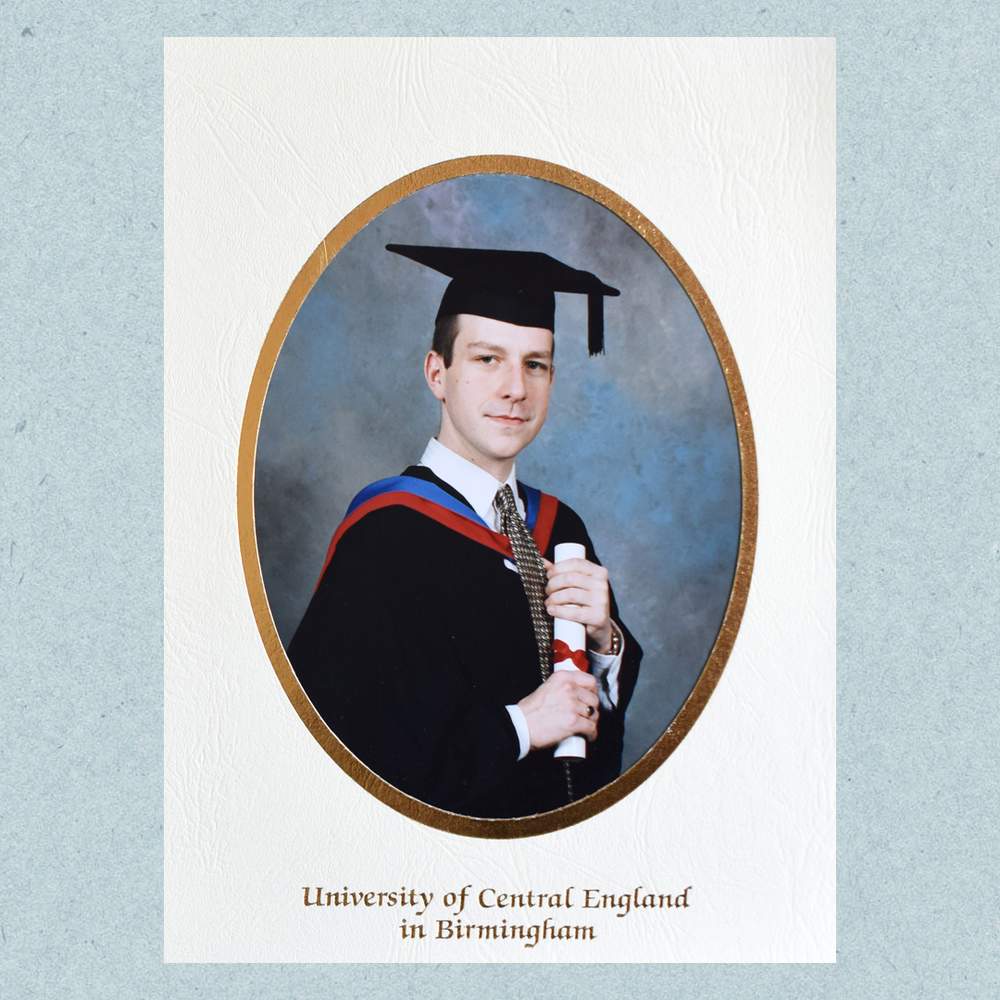

He applied for a diploma course at the University of Central England and was accepted. In his first year, for the first time since his HIV diagnosis, he worked hard at it. “That was a bit of a turning point for me,” he says. His efforts were rewarded with good grades. “It was like: I can actually do this.”

Eventually, the diploma led to a degree. In the meantime, he travelled regularly to Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Birmingham to have his CD4 cells checked – these are usually killed off by the HIV virus, but his count was still normal. Each time they'd give him his results, he’d feel relieved. He’d treat himself to a CD or a video to celebrate.

But although HIV had been the focus of all his worries, the hepatitis C he had also contracted from the contaminated Factor VIII was starting to affect his liver. A biopsy revealed it was scarred and damaged. The doctors suggested he go on a 12-month course of powerful drugs, ribavirin and interferon, in an effort to get rid of the virus. Matt knew from fellow haemophiliacs that the drugs were “pretty nasty”. Some of his friends had had to quit after a few weeks because of the side effects.

At first, taking the drugs was like having the flu. “You’d be curled up in bed, shivering and sweating, for 24 hours after an injection, and you’d have to repeat the process three times a week.” After a while, the side effects faded away, and at the end of the 12 months, the doctors had amazing news for him - he was clear of hepatitis C.

Matt was on the move. Australia was the furthest away he could go from Rugby, from everyone he knew and his entire life up until then. And that’s where he ended up.

“I think I went travelling to get away from myself,” he says. “Fresh people that don’t know me. I could be someone different. I could forget, essentially, what I’d been through over the past few years and the emotional baggage.”

He moved into a two-bedroom house in Sydney with seven other travellers. A close bond quickly formed between them all. They’d work all week and party at the weekends.

Telling people he had HIV seemed easier here. He would only be in their company for a short time. They didn’t know his friends or anything about his life. He was still careful about who he spoke to about it, though their reactions didn’t matter so much to him. “I think within me there was an urge to just get it out,” he says.

But for the first time, he started to contemplate the idea of having a relationship.

Because of his HIV status, the notion had always been a difficult one for him. His parents had drummed into him the imperative to tell prospective partners and give them a choice and it was a far more daunting prospect than telling close friends.

“I met some girls out there and had relationships - brief sort of holiday things, really,” he says. The first girl he told - they’d met travelling - didn’t handle the news well. He’d told her before they first slept together, but later, as the information sank in, her feelings about it began to change. “I think she sort of lived with it for a while,” he says. Then one evening they were both in someone else’s flat with a group of friends. “I just remember, she was sort of crying and her mates were comforting her and so on, and it just went tits up from there.”

After he returned to the UK from Australia, just before Christmas 2000, a thought began to occur to Matt - he might be around for a long time. “I think travelling really helped, it made me see all this stuff, meet all these different people, and I could be… not someone else, but I was free of everything,” he says - including free of preconceptions about HIV. It helped that, with the arrival of anti-retroviral treatments, other people stopped regarding HIV as an automatic death sentence.

In 2003, Matt travelled to Bournemouth for a friend's stag do. In one bar, he found he'd been separated from his friends, so he struck up a conversation with a group of young women who were standing near him. He hit it off with one of them in particular. Before Matt left to rejoin the stag party, he swapped numbers with her.

They kept in touch and soon they were dating. Early in the relationship, he mentioned he had HIV and braced himself for a rejection. “It didn’t faze her,” he says. “At first I didn’t know if it had sunk in, what I’d told her. It was just like, phew.” By 2008 they were married. “It’s not bothered her whatsoever.”

Liz Hooper had two husbands. The same NHS scandal killed them both.

Read her story:

If he'd never imagined it would be possible for him to meet someone, then having children seemed completely off the agenda. “I thought it was physically, medically, impossible,” he says. But one of his childhood friends, a haemophiliac who had also attended the camps in North Wales, told Matt he had become a father thanks to a technique called sperm-washing, a form of assisted conception.

Matt inquired about it and was dumbfounded to be told by a consultant that, because his viral load was still undetectable, it would be safe for him and his wife to have a baby naturally - without sperm-washing.

“I couldn't quite understand what they were saying,” he says. “I was like: ‘Do you not know what I’ve gone through the last 15 or 20 years? Do you think I’m going to subject anyone else to that?'” However low the risk of passing on the virus was, it wasn’t one he was willing to take.

The NHS funded three cycles of sperm-washing, which led to the birth of a son. Matt and his wife applied for assisted conception to have a second child, but this was refused. Despite a supporting letter from Matt’s HIV consultant pointing out that he had contracted HIV and hepatitis C through contaminated blood products supplied by the NHS, they were told these were not “exceptional circumstances”. They had to pay for the treatment that gave them their second son.

Becoming a father was life-changing for Matt. And now, seeing his own boys approach the age at which he was infected brings home the enormity of what happened to him.

“It’s the only time I get emotional about the whole thing,” he says. “It makes me so angry. It’s almost a displaced anger - I don’t feel as if it was done to me, it’s as if it was done to my kids.” If he was told today that his sons had two years to live, he says, “God, I don’t know what I would do, so God knows how my parents felt.”

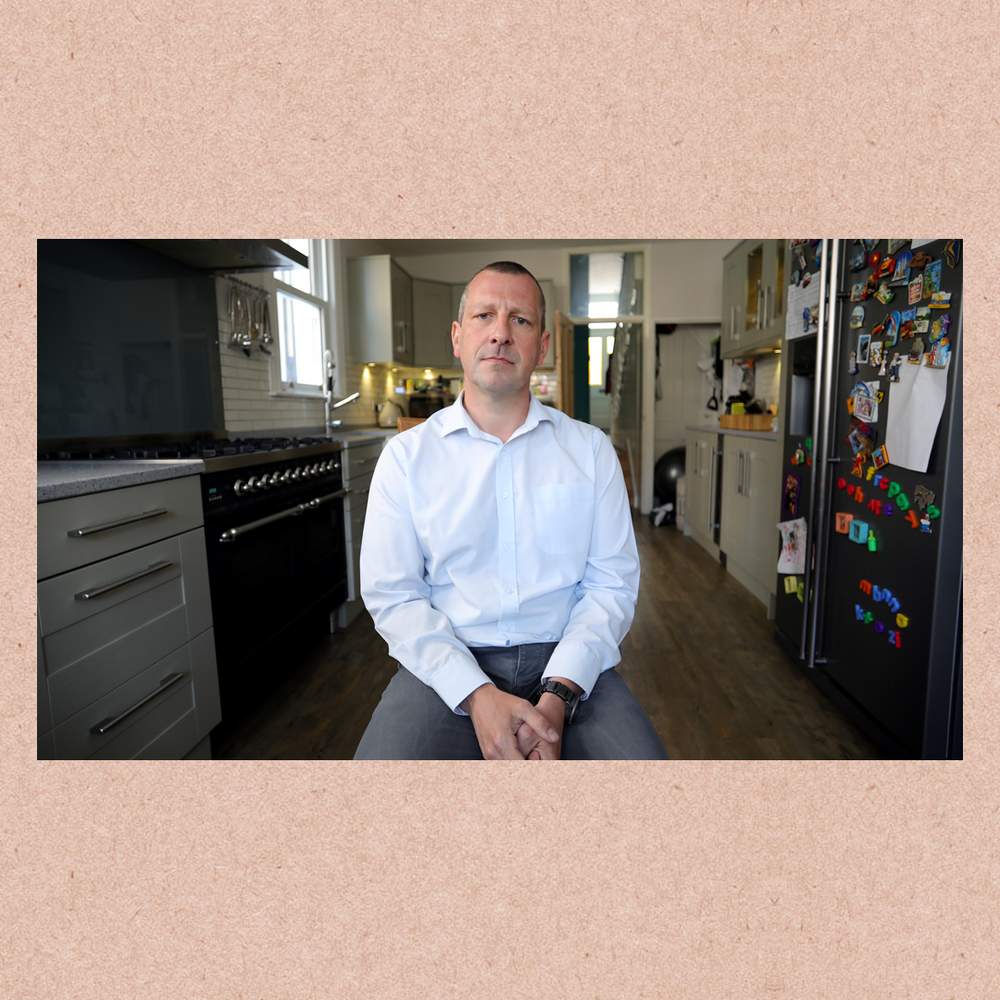

After decades of pressure from campaigners, a public inquiry into the contaminated blood scandal is getting under way – but while Matt is glad it’s taking place, he feels it’s long overdue. “There’s an uproar about the tragedy of Grenfell, and rightly so, but because we’re dying quietly, individually, behind closed doors, no-one knows that,” he says.

Matt looks at where he is today with amazement. His hepatitis C has gone and his viral loads of HIV are still undetectable – he’s never had to take anti-retrovirals. Of about 1,250 haemophiliacs infected with both hepatitis C and HIV due to the scandal, according to the campaign group Tainted Blood, fewer than 250 are still alive. “It really is, in terms of health outcomes, like winning the lottery,” he says.

He has a family and a home in London - he thinks his career is several years behind where it should be, “but actually I'm not too hard on myself because look what I’ve done, I mean, I’m here and I've done it off my own back.”

He knows that many others haven’t been so fortunate. He’s hopeful that the forthcoming inquiry into the contaminated blood scandal will deliver justice, but he won’t allow himself to get too hopeful.

“Successive governments, Labour and Conservative and Liberal Democrat, have failed to address this issue and tried to put it on the back burner or just wait until we’re dead, until it goes away,” he says.

Despite the vast number of victims, the scandal commands relatively little attention because of the legacy of stigma around HIV and Aids, he believes – which is why he is telling his story.

“I'm pleased with where my life is at the moment - I’ve got a brilliant family, a wonderful wife, two wonderful kids,” Matt says. “I’ve got everything to be thankful for. But I shouldn’t have to be thankful for that.”