It looks like the set of Game of Thrones. Wolin in Poland hosts one of the world’s largest gatherings of Viking enthusiasts each year.

Hundreds come to recreate Viking culture - and take part in fierce, competitive battles. Many are drawn by a passion for history. But, for a significant number, it’s a way of escaping their past - a past scarred by violence.

The Viking scene attracts people who are combat veterans, former football hooligans, and others struggling to come to terms with violence.

It also seems to appeal to men who have lost direction in their lives, and are looking for a sense of purpose.

Four members of the international group called the Jomsborg Vikings, which is about 2,000 strong, explain what draws them to the Viking world, and how it has changed their lives.

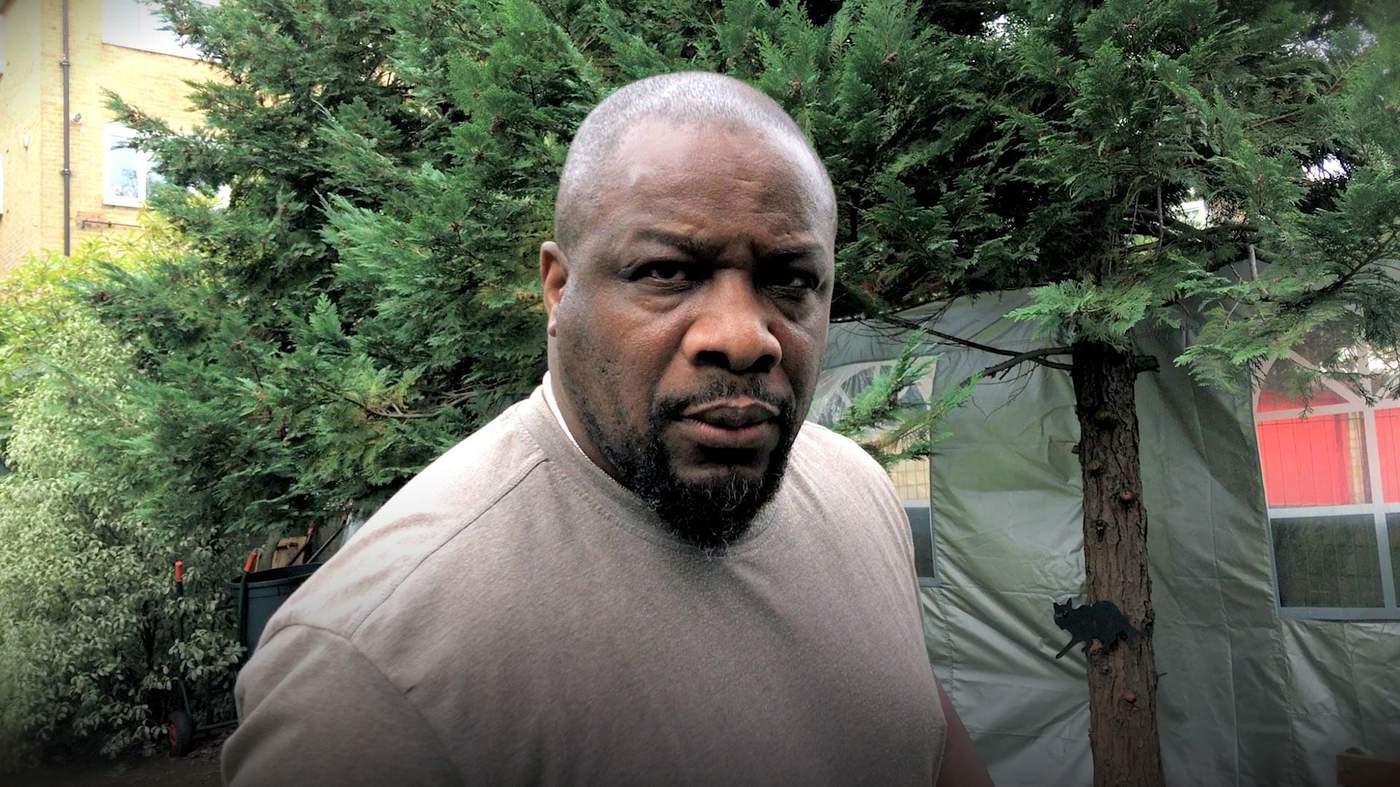

Max Bracey - or Maximas von Bracey, to give him his Viking name - leads a British Viking contingent called Ulflag.

His day job is running a shop that sells Viking paraphernalia in Walthamstow, London.

“A lot of these people are adrenaline junkies,” he explains.

“They really want to take part in something where they feel alive, with a sense of brotherhood.”

It gives them a release of the natural violent urges that we humans have.”

He continues: “This is [also] a way of exploring how our ancestors lived.”

He embraced Viking re-enactment at a low point in his life.

His father had died of cancer, and a long-term relationship with his girlfriend had come to an end.

He tried various martial arts, but none fully satisfied him.

Max Bracey - or Maximas von Bracey, to give him his Viking name - leads a British Viking contingent called Ulflag.

His day job is running a shop that sells Viking paraphernalia in Walthamstow, London.

“A lot of these people are adrenaline junkies,” he explains.

“They really want to take part in something where they feel alive, with a sense of brotherhood.”

It gives them a release of the natural violent urges that we humans have.”

He continues: “This is [also] a way of exploring how our ancestors lived.”

He embraced Viking re-enactment at a low point in his life.

His father had died of cancer and a long-term relationship with his girlfriend had come to an end.

He tried various martial arts, but none fully satisfied him.

Qanun Bhatti is the chief trainer of the Ulflag Vikings in the UK.

He suffered abuse as a child, when he was six years old.

“I had quite a lot of anger issues. Violence just became a bit of a way of life.

“An angry child doesn’t know how to deal with emotions, [except] by being violent.”

Even as he was struggling to come to terms with the abuse, he had more violence to deal with in his adolescence.

Growing up in London in the 80s and 90s, he says he was victimised for being Asian and Muslim, picked on at school and attacked by skinheads.

Qanun believes joining the Vikings has healed him.

“Being able to let out my frustrations and aggression in a controlled manner is very beneficial for me.”

It has also given him a new sense of belonging.

[I feel] accepted and for want of a better word, loved.”

Qanun has experienced racism within the Viking world, too. People have commented that he should be playing the part of a slave, on account of the colour of his skin, he recalls.

But according to Qanun the true Viking message, which the Jomsborg Vikings try to promote, is one of tolerance and diversity.

“Vikings were so curious about anything that wasn’t the norm, it was part of their special culture. They were inveterate explorers.

“If someone walked in and was a different skin colour, rather than being: ‘You are different to us, we are afraid,’ they’d be like: ‘Wow, who’s this? We want to know about this person because they are different to us.’ They were excited.”

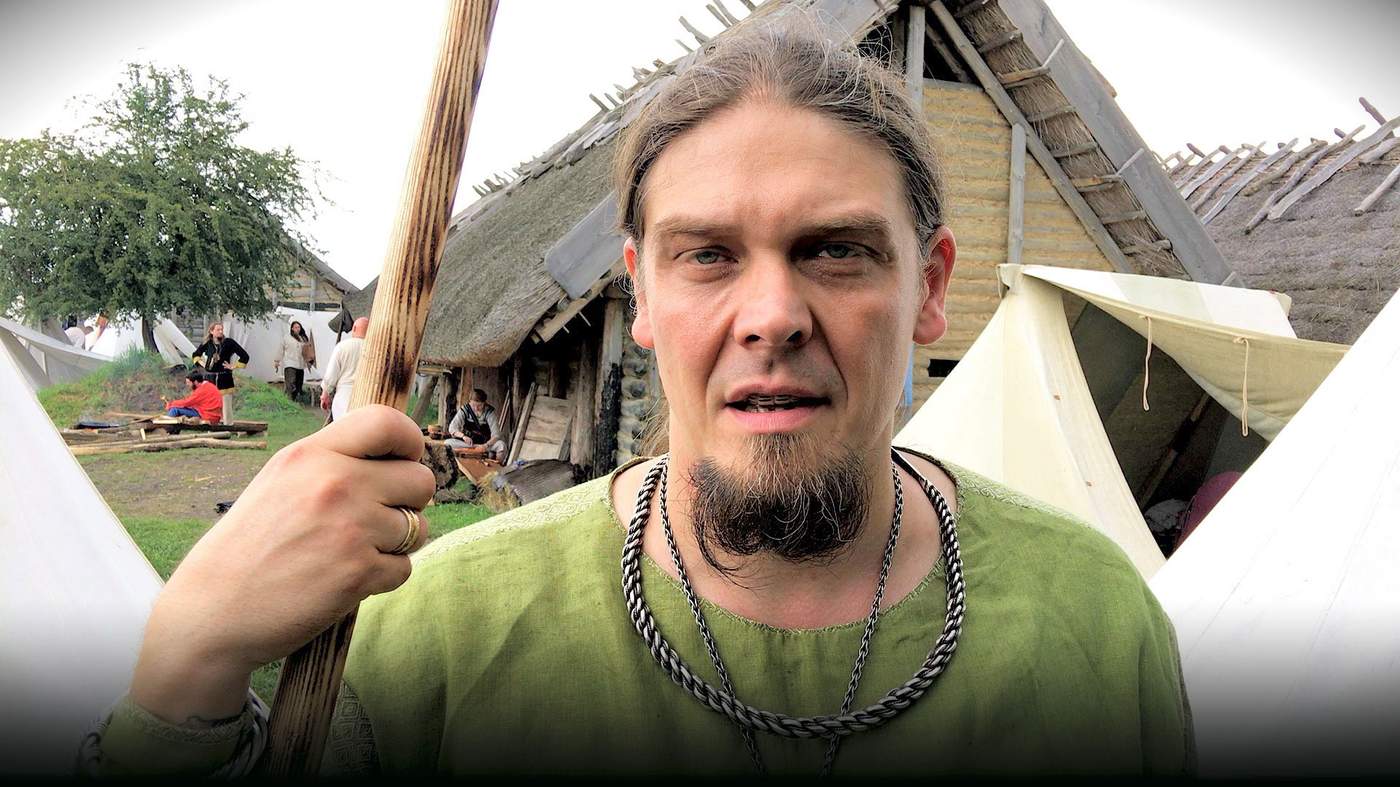

Igor Gorewicz has been organising the battles at the Wolin Festival in Poland since the late 1990s.

He says he has seen it transform the lives of hundreds of men.

People who had problems in their lives became good Viking citizens by releasing their aggression in a moderate way.”

The change can take effect after just a week of Viking martial training, he reckons.

The Viking code is all about creating strong men who know how to behave well, says Igor:

It allows you to be a tough man, while still respecting others. It also allows someone to escape the baggage of their past because one's Viking reputation rests purely upon their actions in the Viking world.

Igor, himself, used to be part of a violent scene in Poland called ‘metal-heads’. He describes it as football hooliganism, without the football.

Igor now takes his Viking message to schools and correctional facilities for young offenders.

He believes he can reach out to troubled young men that traditional authority figures, like teachers or magistrates, cannot.

Igor admits that the world of Viking re-enactment does draw a minority of people with racist views, attracted to the idea of re-creating a white, warrior culture.

“In all the cases I know, when they join our society, after a short time, they stopped talking bullshit.”