Roland Williams is addicted to micro-adventures.

Almost every other weekend, he escapes the city by driving out to Wales, the Lake District or Scotland, to embark on a solo expedition in the mountains. He takes a one-man tent and enough supplies to last for three days.

It's something he's been doing for several years, and he sees it as a way to detox from the city, returning to London fresh and rejuvenated.

Last year, doctors in Shetland began prescribing hiking and mountain walks, among other outdoor activities, as a way of combating health issues such as stress, anxiety and depression.

Since then, NHS England has said it will recruit more workers trained to prescribe exercise groups and art classes.

I wanted to test the idea of using nature to boost wellbeing by escaping to the mountains at the end of a working week. The benefits sounded encouraging.

Roland Williams

I met up with Roland in an East London café, where I pitched the idea of documenting him on one of his weekends away.

The plan was to drive to Snowdonia National Park on the Friday evening and stay until Monday afternoon, which meant three full days of hiking.

On the Friday, I trekked through the chaos of London's streets, hauling my gear, desperate to get away.

Roland Williams is addicted to micro-adventures.

Almost every other weekend, he escapes the city by driving out to Wales, the Lake District or Scotland, to embark on a solo expedition in the mountains. He takes a one-man tent and enough supplies to last for three days.

It's something he's been doing for several years, and he sees it as a way to detox from the city, returning to London fresh and rejuvenated.

Last year, doctors in Shetland began prescribing hiking and mountain walks, among other outdoor activities, as a way of combating health issues such as stress, anxiety and depression.

Since then, NHS England has said it will recruit more workers trained to prescribe exercise groups and art classes.

I wanted to test the idea of using nature to boost wellbeing by escaping to the mountains at the end of a working week. The benefits sounded encouraging.

Roland Williams

I met up with Roland in an East London café, where I pitched the idea of documenting him on one of his weekends away.

The plan was to drive to Snowdonia National Park on the Friday evening and stay until Monday afternoon, which meant three full days of hiking.

On the Friday, I trekked through the chaos of London's streets, hauling my gear, desperate to get away.

At 00:30, after a four-hour drive, we reached the small wooden hut that was to be our weekend home. There was nothing but silence. Just the gentle crackle of rain on our low, felt roof.

I got into my sleeping bag and sank into a deep sleep.

Morning came, and the weather was looking uninviting.

Roland offered some sound advice on how to pack for a day in the elements: “There’s no such thing as bad weather, just bad kit and bad planning,” he said, lacing up his boots.

Up in the mountains it soon became clear why Roland does what he does.

I got lost in my own thoughts. I felt in control.

The first day in Snowdonia was the toughest.

A few days before this trip, I’d seen the documentary Free Solo, about Alex Honnold, who had climbed the face of El Capitan in Yosemite Park without any ropes. Something he said in that film had stuck with me: “Nobody ever did anything great by staying cosy and warm.” Those words echoed in my mind as we pushed through 70mph winds and near zero visibility.

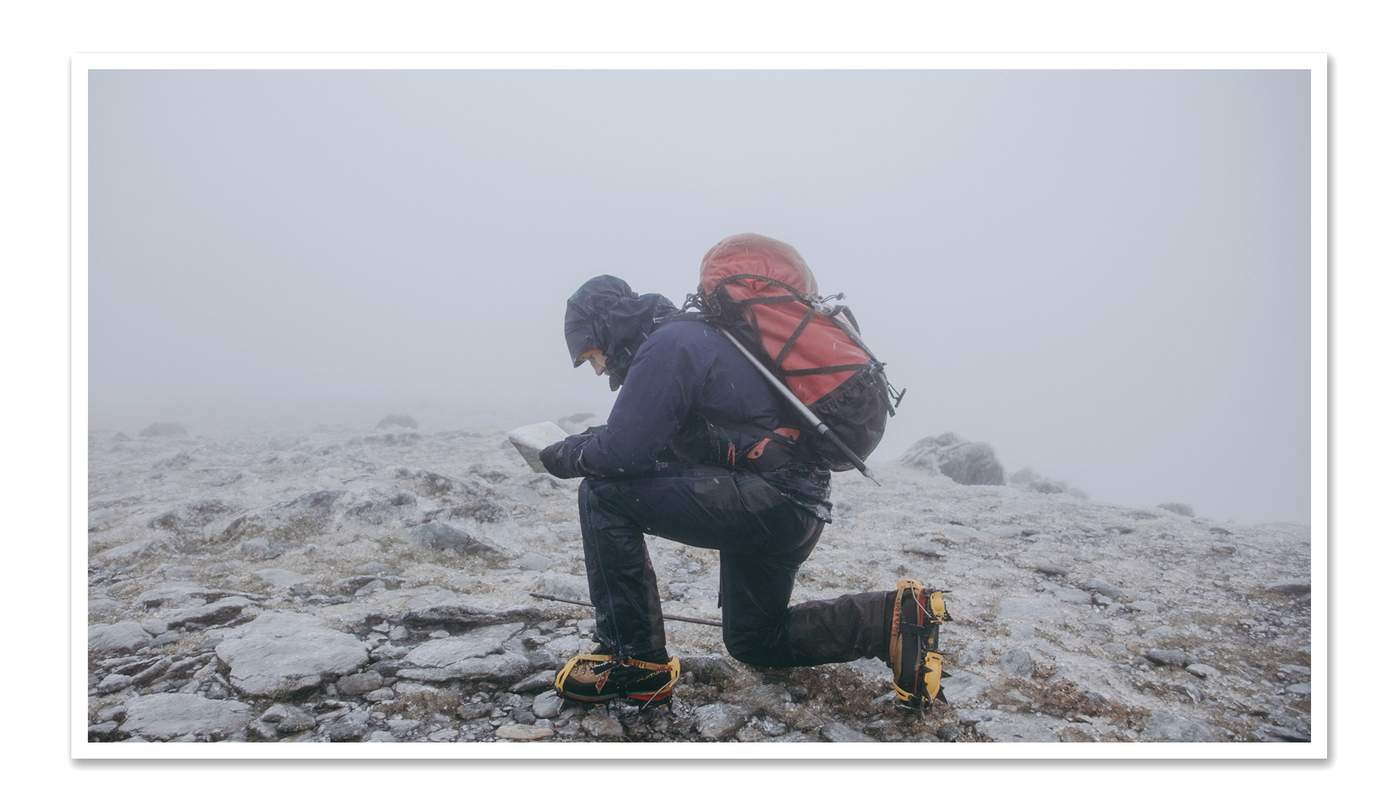

Ice formed on our bags, the zips on our jackets and in our beards. At one point, a thick layer of ice had formed on the rocks beneath our feet, forcing us to put on crampons for extra grip.

Morning came, and the weather was looking uninviting.

Roland offered some sound advice on how to pack for a day in the elements: “There’s no such thing as bad weather, just bad kit and bad planning,” he said, lacing up his boots.

Up in the mountains it soon became clear why Roland does what he does.

I got lost in my own thoughts. I felt in control.

The first day in Snowdonia was the toughest.

A few days before this trip, I’d seen the documentary Free Solo, about Alex Honnold, who had climbed the face of El Capitan in Yosemite Park without any ropes. Something he said in that film had stuck with me: “Nobody ever did anything great by staying cosy and warm.” Those words echoed in my mind as we pushed through 70mph winds and near zero visibility.

Ice formed on our bags, the zips on our jackets and in our beards. At one point, a thick layer of ice had formed on the rocks beneath our feet, forcing us to put on crampons for extra grip.

With Roland’s guidance, we reached the summit and began our descent back to the valley floor.

There’s nothing quite like the feeling of sipping a hot cup of tea after six hours of freezing rain hitting you in the face. With no television in our wooden hut, I found that I appreciated a few simple things more than ever before. To curl up in a warm sleeping bag and drift off to sleep at 22:00 was a luxury in itself.

The following day started off drier. No rain, clear skies. We gathered our gear and drove out to the same valley as the day before, just 10 minutes away.

“You see that ridge? We’re going up there,” Roland said excitedly. “I doubt we’ll see anyone using that route today.”

The mountain, Tryfan, is a popular scramble for keen mountaineers. The icy winter conditions we faced made it unattainable for those who hadn’t brought the right gear. Fortunately for us, Roland had pre-planned the routes, checking and re-checking weather conditions, and had produced a kit list for the conditions he’d expected. There wasn’t much that stood in our way.

And so, we began our ascent.

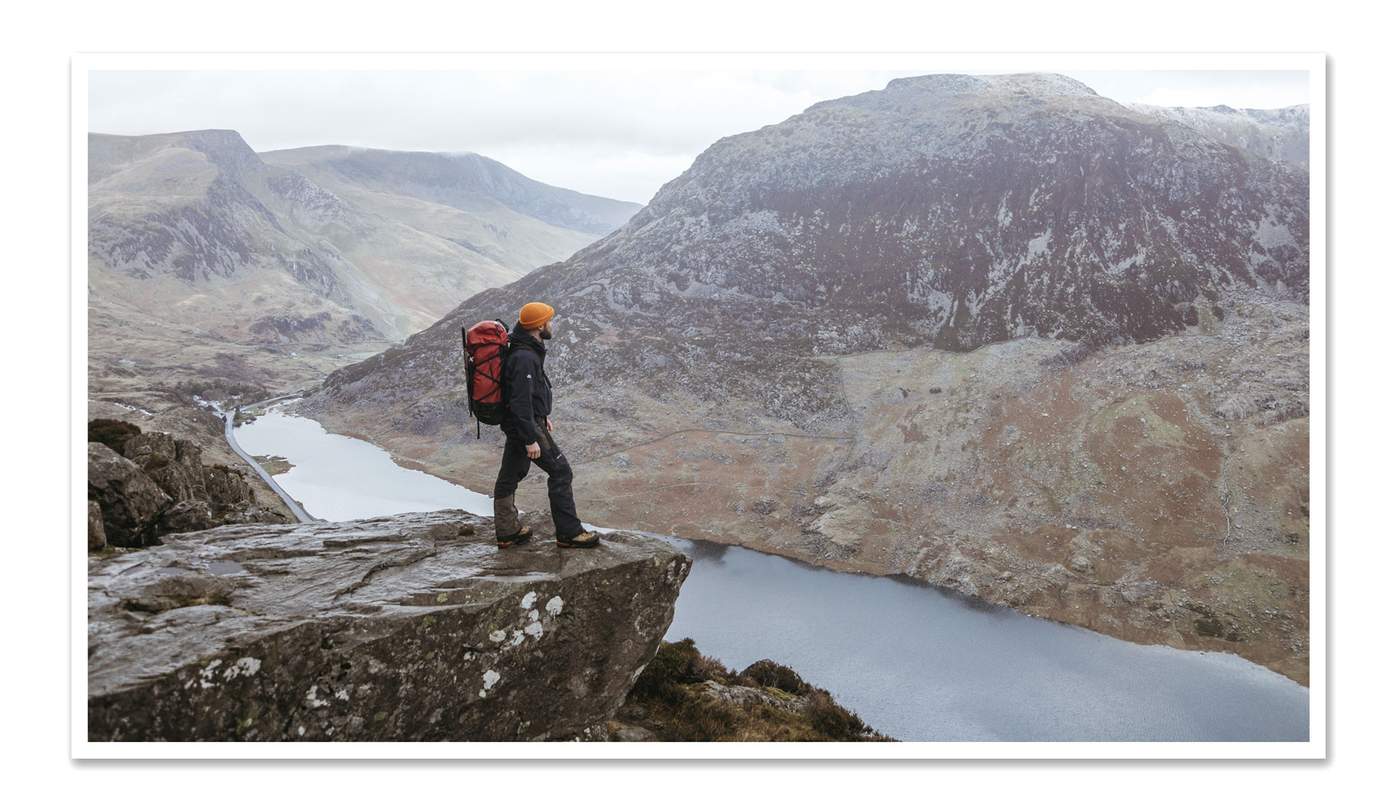

Halfway up, a huge rock jutted out over the valley. The clouds cleared and we could see for miles. Roads below played host to what looked like toy cars on a children's play mat. Roland perched on the edge looking out towards the horizon. He appeared for a moment like the figure in Caspar David Freidrich’s Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog. How strange that that famous painting was created 200 years ago, yet still we are embarking on similar expeditions to take advantage of these unchanged views.

The higher we went, the colder it got, as again more ice began to form underfoot. Roland was right when he said we would be alone on this route. The only glimpse of other hikers came in the form of footprints in the frozen mud. The isolation felt therapeutic.

We reached the summit of the day’s route in high spirits. The scramble to the top was much more physically demanding than the day before.

Fortunately, the wind was not as strong, although the rain began to fall as Roland paused to take a new bearing for our descent.

We hiked down, making it back to the car as the sun began to fall, after nearly nine hours in the mountains. Our evening plans were similar to the night before - a hot meal, a beer in a local pub, then sleep.

Our final day was to be the most rewarding of all.

We woke up at 05:30. The plan was to be on the mountain for sunrise.

Standing in the car park, I looked up towards the peak of Snowdon, which was hidden behind the clouds. Head torches on, map at the ready, we set off.

Roland and I hardly spoke for the first 90 minutes or so. We found a rhythm in our pace and stuck to it. It was pitch black, but you could still feel the mountains looming over us as strips of light began to break over the crest of the ridge to the east.

At 08:30 the sun rose. There was another moment of calm as we stood silently watching the orange glow over the small lodge in the distance, a few hundred metres below.

As a reward for reaching altitude, Roland fired up the stove. We enjoyed a hot breakfast with the sunrise in the distance and the peak of Mount Snowdon in our sights.

This was not my normal Monday morning but it was by far one of the best.

After breakfast, I asked Roland why he is so passionate about the mountains. He told me that he loves his family, and his job as a chartered surveyor. He also enjoys the social aspect of living in London. But being able to walk alone in the wilderness is another part of his identity. When he escapes the city for a micro-adventure, it is just him and the elements. This is something he's keen to share and has been training for his mountain leader award.

Adventures can be as big or small as you make them. It takes a lot of courage to step outside of the place you feel most secure. But for the benefit of our mental health, I believe it is essential.

As American author Jack Kerouac said: “In the end, you won’t remember the time you spent working in the office or mowing your lawn. Climb that goddamn mountain.”

Well I’m sure glad I did, and let’s hope it’s the first of many.