Claudia Lawrence’s house remains empty, preserved by her family in the hope she might one day return.

For years her dresses hung unworn in the wardrobe, some with tags still attached. The remnants of her belongings are now pushed against the walls in haphazard piles.

In the decade since she vanished - presumed murdered - a number of significant dates have passed, including her 40th and 45th birthdays. For her friends and family, it has been an unbearable time.

Three days into the investigation, Claudia’s friends couldn’t imagine it going on another week, let alone a decade. They felt sure she would turn up.

That changed for Suzy Cooper moments after the landlord of the Nag’s Head pub called to say the press were there and wanted to talk to her.

She was wholly unprepared for what greeted her.

Claudia and Suzy were so close they called each other “sister”

“I opened the door and every paper and news channel you could imagine were there. Microphones and cameras were shoved in my face, people asking me this and that. It was horrendous.

“It really hit me on the Saturday night when I saw the story on the news. I remember thinking ‘oh Claudia would hate that picture’ - she really disliked her picture being taken.

“I thought it was going to be over in a day or two, for sure. How this has gone on for 10 years with no resolution, no clue, no nothing, I can’t fathom.

“How can that happen in this day and age?”

“I regularly go out for a walk. It might be a nice sunny day and I wonder ‘Claudia, are you seeing this?’”

Hands clasped in his lap, Peter Lawrence glances at a candle on the fireplace at his home in York, less than two miles from his daughter’s small terraced house in Heworth.

The red wax pillar was given to him by the Archbishop of York as a symbol of hope in the bleak years following Claudia’s disappearance.

Ali and Claudia were three years apart in age

Peter and his ex-wife Joan had two children - Ali, born in 1971, followed three years later by Claudia. They brought them up in Malton, a North Yorkshire market town with strong horse racing connections, 16 miles from York.

It was a comfortable upbringing. Claudia played the flute and on Saturdays the sisters would go for riding lessons in nearby Rillington. Horses became a life-long passion for the younger girl and she continued to ride until the time she disappeared.

The family’s five-bedroom home had paddocks and the girls had their own ponies. In the winter the family looked after donkeys from Scarborough beach and their garden was used as a sanctuary for the animals to recover from a busy summer on the sand.

Claudia’s teenage years were seemingly as content as her childhood - she would wander into the market square with friends and occasionally babysit for Peter’s friend Martin Dales, whose two daughters thought she was “glamorous”.

Ali and Claudia went to nearby private schools and while close, were different in character.

“Ali was more academically minded while Claudia was brave, adventurous, always wanting to do things,” says Peter.

“She would go out for long rides and would help mucking out at the stables. She enjoyed school, although maybe not the work as much. But she was happy and had a lot of friends.”

Claudia went on to study catering and by the time she was in her early 20s, she had worked in various kitchens before joining the University of York as a chef.

Joan said she was a well-liked employee, the type who would volunteer for shifts at Christmas so colleagues could spend it with their children.

“Chefs are not particularly well paid unless you get to be famous,” adds Peter. “But she had no aspirations to do that - she was really happy doing what she was doing.”

It was working in York that prompted Claudia to move. She had become nervous about driving there in winter, so she bought a neat terraced house with a green door on the outskirts of the city centre.

Heworth Road is dotted with typical suburban landmarks: a post office, a primary school, a Costcutter shop and a church on the corner. The Nag’s Head, a stone’s throw from her gate, was Claudia’s regular and the place where she often socialised with friends.

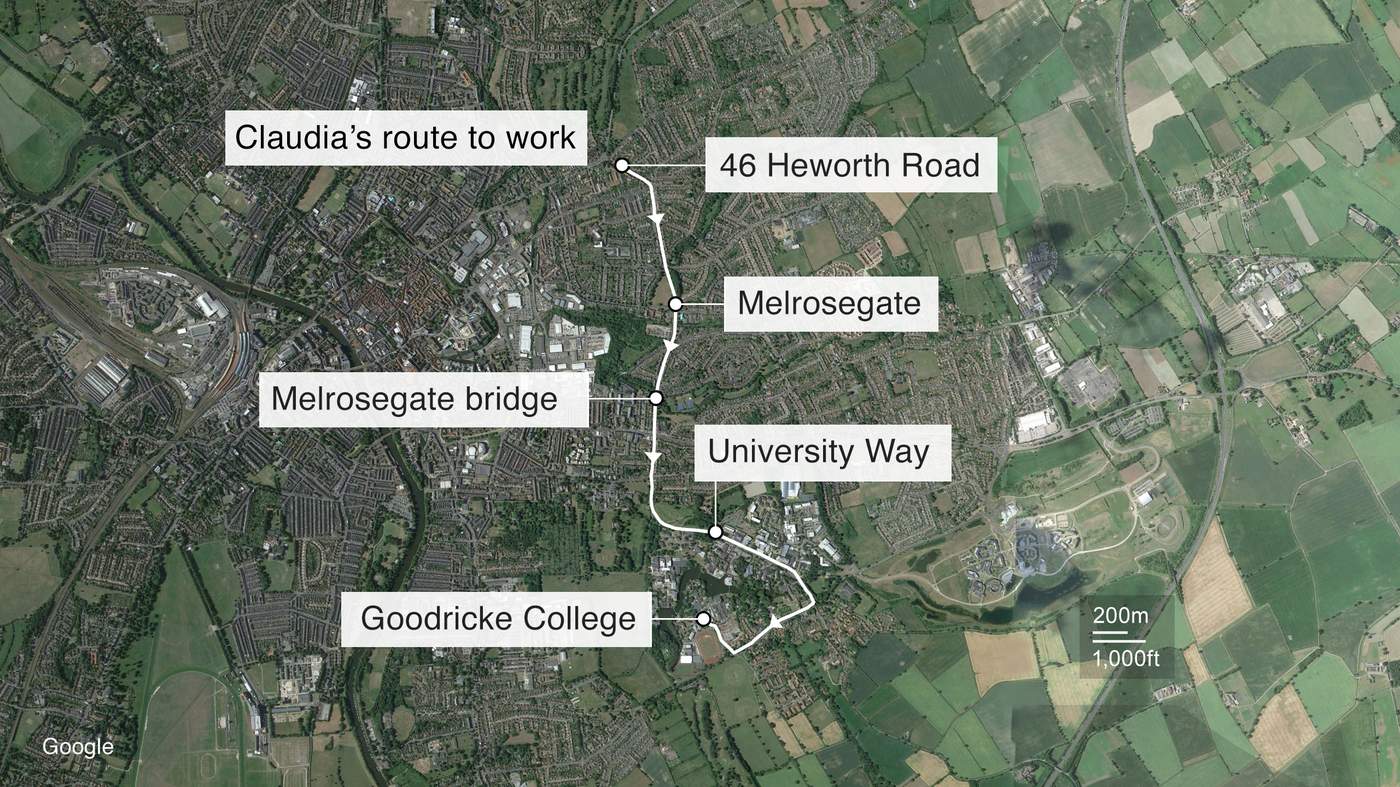

Her home was also a 10-minute car journey to her job at Goodricke College on the university’s Heslington campus. But according to Joan, Claudia had been walking to work in the days leading up to her disappearance on Thursday, 19 March 2009, because her ageing Vauxhall Corsa was in the garage.

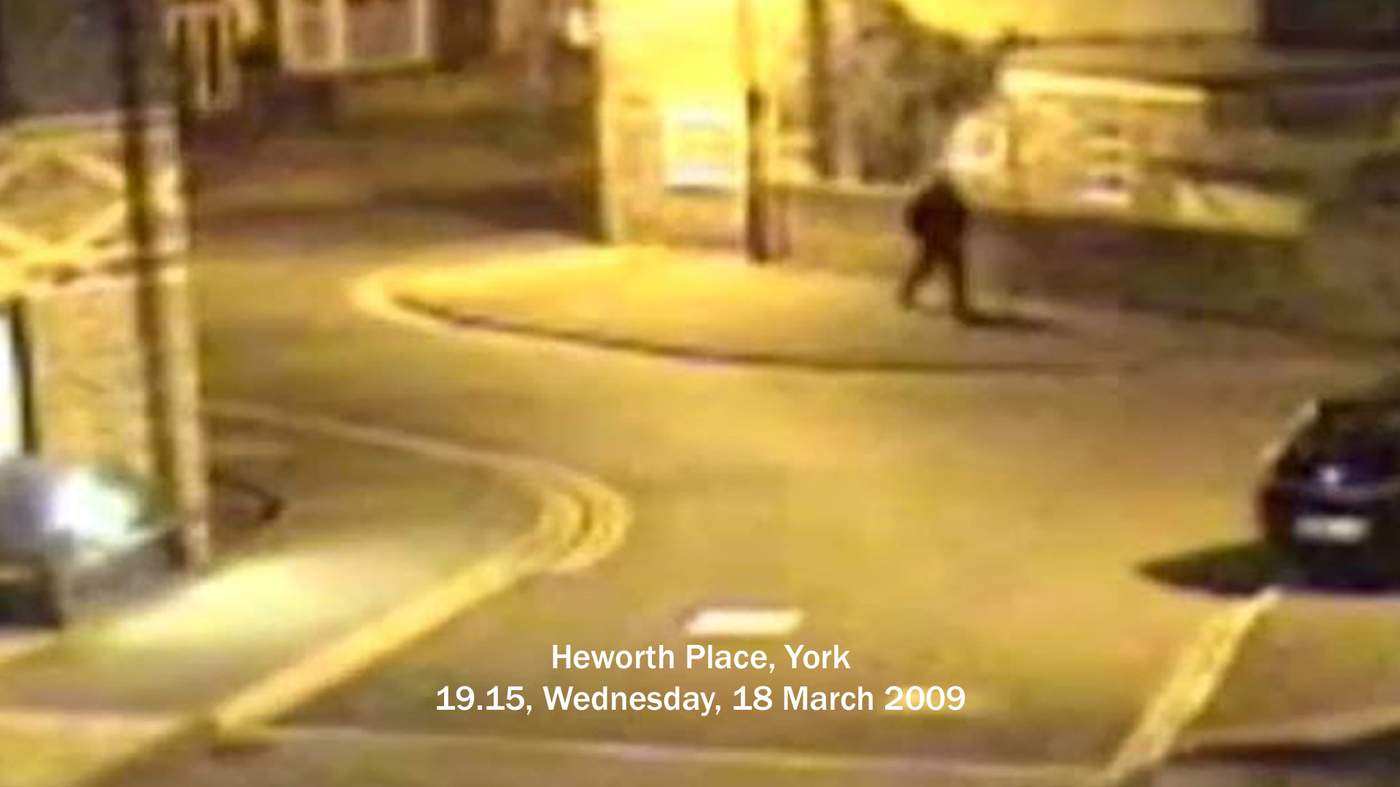

Indeed, the 35-year-old was seen walking home from work the day before - cameras capturing her as she left work at 14:31 and spotting her at various points along the 45-minute route. Later that night, she spoke to Peter on the phone, then Joan, with whom she made plans to mark Mother’s Day.

Claudia purchased the house in Heworth Road in 2007

“We’d both been watching Location, Location, Location on the television,” says Joan.

“It was being filmed in Harrogate, and we have a friend there, so we just chatted about that.

“She seemed absolutely fine.”

“I dream about Claudia - we always talk about why she’s been missing and there’s always a different explanation.

“I like the dreams because in some sort of way I’ve seen her but it really shakes me for the rest of the day. It’s almost like I don’t want to go back to reality, I just want to stay in the dream with her.”

Suzy Cooper was sitting alone in the Nag’s Head waiting for Claudia to show up on the evening of 19 March when she realised something wasn’t quite right.

The pair had arranged to meet for a cider, as they so often did. But when her friend failed to arrive Suzy sent her a text, joking about being “stood up”. When she called and it went straight to voicemail, she chalked it up to Claudia falling asleep and leaving her phone uncharged.

“I was off work that week so the next morning, the Friday, I rang her and again it was switched off. That was totally out of character and at that point I knew something was wrong.”

Suzy, Claudia and Jen King were part of a tight-knit group that regularly met at the Nag’s Head.

The trio formed a close friendship soon after meeting at the pub in 2006 and spent several nights there a week. When they weren’t together, they were constantly texting or chatting on the phone.

“We’d listen to each other moan, talk about our days or, if we were having a stressful time at work, then we’d say ‘oh, come on let’s just have a drink’,” says Jen.

Claudia, Suzy, and Jen were close friends

Suzy and Claudia were so close they rarely called each other by their first names, instead calling each other “sister”. While Jen, who was a barmaid at the pub, lived for a few months with Claudia in Heworth Road.

“She was a simple person, in that she was fairly easily pleased,” says Jen.

“She liked to buy a new top now and again, go to the pub, see her horse, listen to music. She didn’t desire the grand things in life, she just wanted a nice sunshine holiday and to have a tan.”

It was this predictability that tipped Suzy off. When she couldn’t get hold of Claudia again the next day, she immediately rang Peter.

“I told him Claudia hadn’t turned up when we arranged to meet and that she hadn’t answered my calls and that I was really worried. He drove straight over.”

The pair were nervous as they entered Claudia’s house on 20 March. They feared she had been attacked or fallen down the stairs but the total absence of anything out of the ordinary was even more concerning.

Her slippers were neatly by the door, dishes stacked in the sink. The jewellery she typically took off for work and left at home was on the chest of drawers.

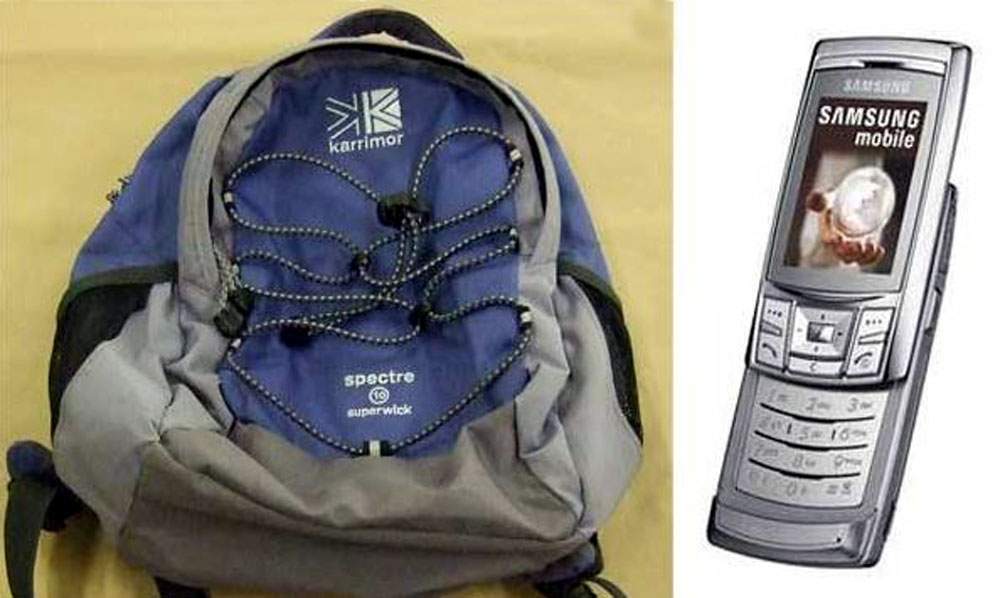

In the kitchen, next to the bathroom, her toothbrush had been left on the draining board. Her phone and rucksack containing her chef’s whites were missing. Everything suggested she left for work as planned.

Peter Lawrence spoke to his daughter the night before she vanished

Peter had already called the university and learned his daughter had not turned up for her shift the previous day. He walked outside, sat alone in his car and called 999 to report her missing. Within hours, Heworth was swarming with police.

“When I called I expected them to say - given how long she’d been missing - to give it a day or two, but it was the complete opposite,” he says.

“There were about 150 to 200 officers combing every inch of the route she would have taken to the university. It just all seemed very surreal.”

According to police, the first 72 hours of a missing persons inquiry are the most critical.

The intensity of the searches in and around Claudia’s home in those first few days reflected the fact that detectives knew they were working against the clock.

But despite the speed at which North Yorkshire Police descended on Heworth Road, Claudia’s mother believes the initial investigation was plagued with mistakes from the outset.

“In my mind the police were out of their depth,” says Joan. “It got so big, so quickly, that they didn’t know how to handle it.”

York Press newspaper reporter Nicola Small was at work when North Yorkshire Police made its first media appeal two days after Claudia’s disappearance.

“I remember being struck by the photo of her - she stood out. A smiling, attractive blonde who didn’t look like she’d had a troubled life.

“There was nothing [in the press release] to suggest we wouldn’t soon be getting another saying she’d returned home safe and well.”

Joan Lawrence is critical of the police for using this photo of Claudia

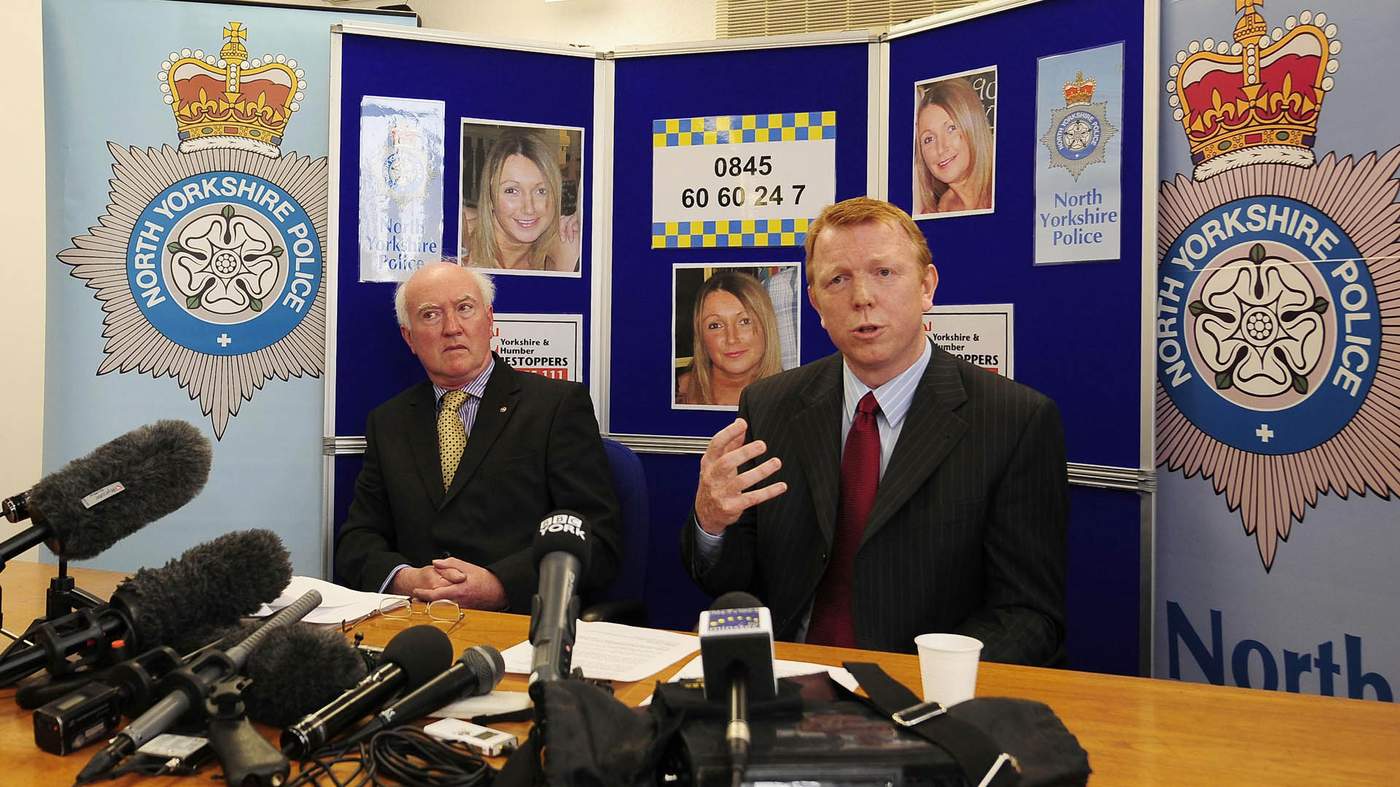

But by Sunday, a second appeal struck a more worrying tone. A high-ranking officer had been assigned to the case and a press conference arranged for the next day.

Chief reporter Mike Laycock suspected Claudia’s disappearance wasn’t a typical missing persons case and decided to put the story on the front page of Monday’s newspaper. He was right to follow his instinct.

The next day, Det Ch Insp Lucy Pope told journalists she feared Claudia had been abducted. Sitting alongside her was a visibly shaken Peter, who described the wait for news as a “living nightmare”.

“I just remember his face,” says Jen, who saw him later that day at the police station. “[I remember] him saying ‘things like this don’t happen to us’.”

In York - a tourist city known for its Viking heritage and Gothic cathedral - the story struck a nerve, says Nicola.

“Everybody wanted to know what the latest developments were and everybody had their own theory about what had happened.

“These things didn’t happen here. Young women with everything to live for didn’t vanish without trace.”

The case was handed to one of North Yorkshire Police’s most senior officers, Det Supt Ray Galloway. It quickly became the biggest investigation the force had dealt with in several years.

Posters of Claudia were plastered on lampposts across the city and officers trawled Heworth, combing through undergrowth, checking a nearby stream and speaking to neighbours.

Images of a bag and phone similar to Claudia’s missing items were released

Her house was searched and largely discounted as a crime scene because there were no signs of struggle or foul play. A suggestion Claudia had left the country to live in Cyprus, where she had holidayed numerous times, was also dismissed because her bank cards and passport were in the house.

Claudia left few digital clues as to her whereabouts. She didn’t use social media, own a computer, or use the internet on her Samsung D900. Unlike smartphones today, hers did not track her location.

She was, however, a prolific texter. She replied to a message at 20:27 on 18 March but failed to respond to one received at 21:12. Analysis of her phone showed it was deliberately turned off at 12:10 the next day within an eight-mile radius of York.

Detectives were certain Claudia had left for work on 19 March and that something had happened to her between Heworth Road and Goodricke College.

A number of witnesses came forward, including a cyclist who saw a woman that morning matching Claudia’s description, talking to a man dubbed by police as “the left-handed smoker”.

They were spotted near the electricity substation at Melrosegate bridge at about 05:35. It was potentially significant because if Claudia had left for work as planned, she would have reached the bridge - a 10-minute walk from her house - by that time.

A witness reported seeing a man and a woman talking by the bridge

But it was not as far as the CCTV camera at the Melrosegate shops which had captured her walking home from work on 18 March, suggesting she never made it that far on foot the next morning.

A different witness, however, came forward to report seeing a man and woman arguing on a grass verge next to a parked vehicle on University Way, around the time Claudia was due to start her shift.

Both sightings were major lines of inquiry but despite numerous appeals, neither couple was ever traced.

Six weeks after Claudia’s disappearance, the investigation was reclassified as a suspected murder case. While there was no body, crime scene or suspect, there was no proof of life either.

Joan says she found out about the latest development in her daughter’s case from a TV news report. “I got such a shock, I couldn’t believe it,” she says.

Joan Lawrence says she will never give up hope

Joan has long been critical of the first police investigation. She says officers initially used a photo of Claudia with the wrong hair colour and that she wasn’t spoken to in the immediate aftermath of her daughter’s disappearance.

“Ray Galloway came to see me once, a few days [later]. He never asked me what Claudia was like, what her hobbies were, he didn’t want to get to know her.

“I told [police] that she didn’t look like that when she disappeared - her hair was much darker, but they carried on using that [photo] for a number of years.”

Joan with Ali, left, and Claudia

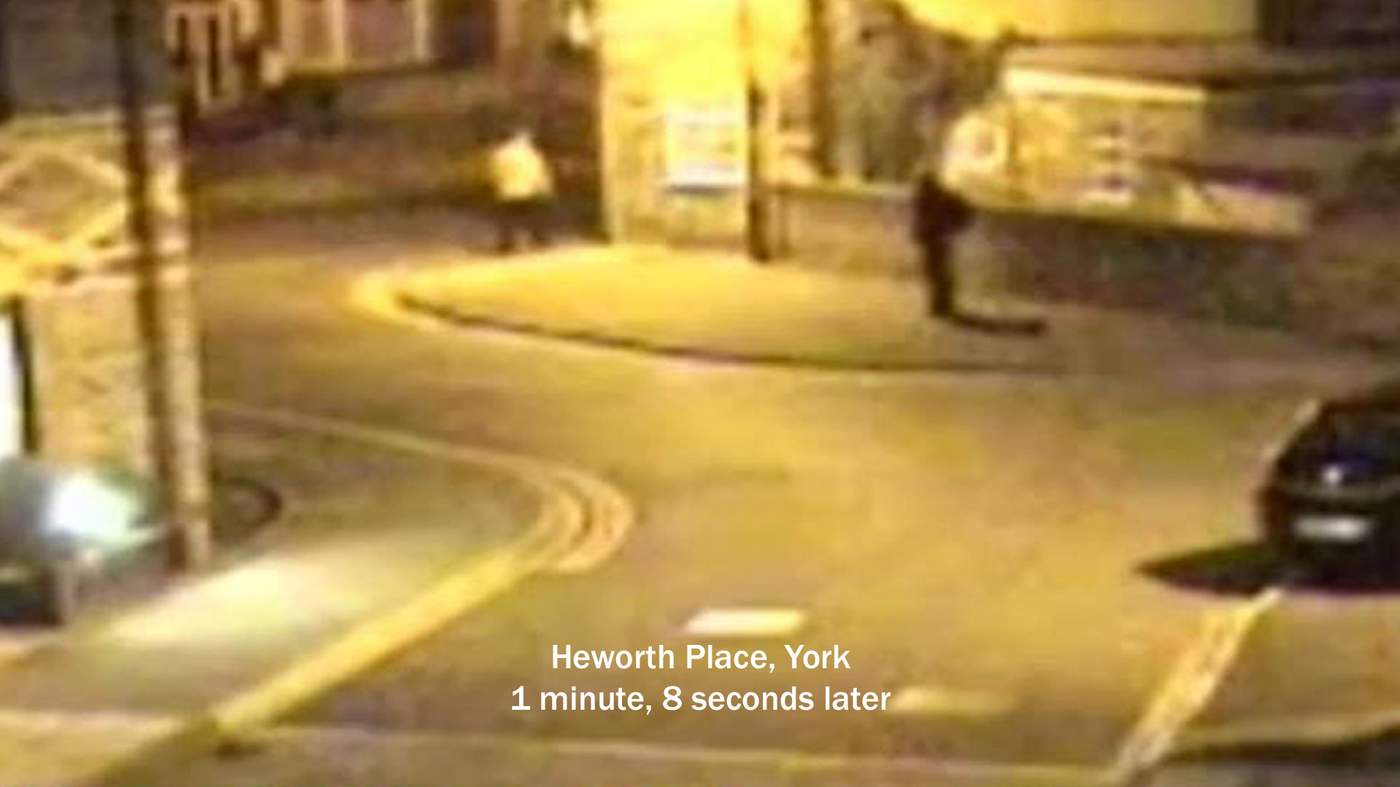

As the weeks passed, police were seemingly getting no further. Detectives hoped CCTV released in mid May of a man seen near Claudia’s home the morning of her disappearance might provide a crucial clue.

At 05:07 he can be seen walking into Heworth Place towards an alley behind her house. Just over a minute later, he reappears and rejoins the main road.

Mr Galloway told the York Press at the time that the man’s actions were “strange” and urged him to come forward so he could be excluded from the inquiry. He has never been identified.

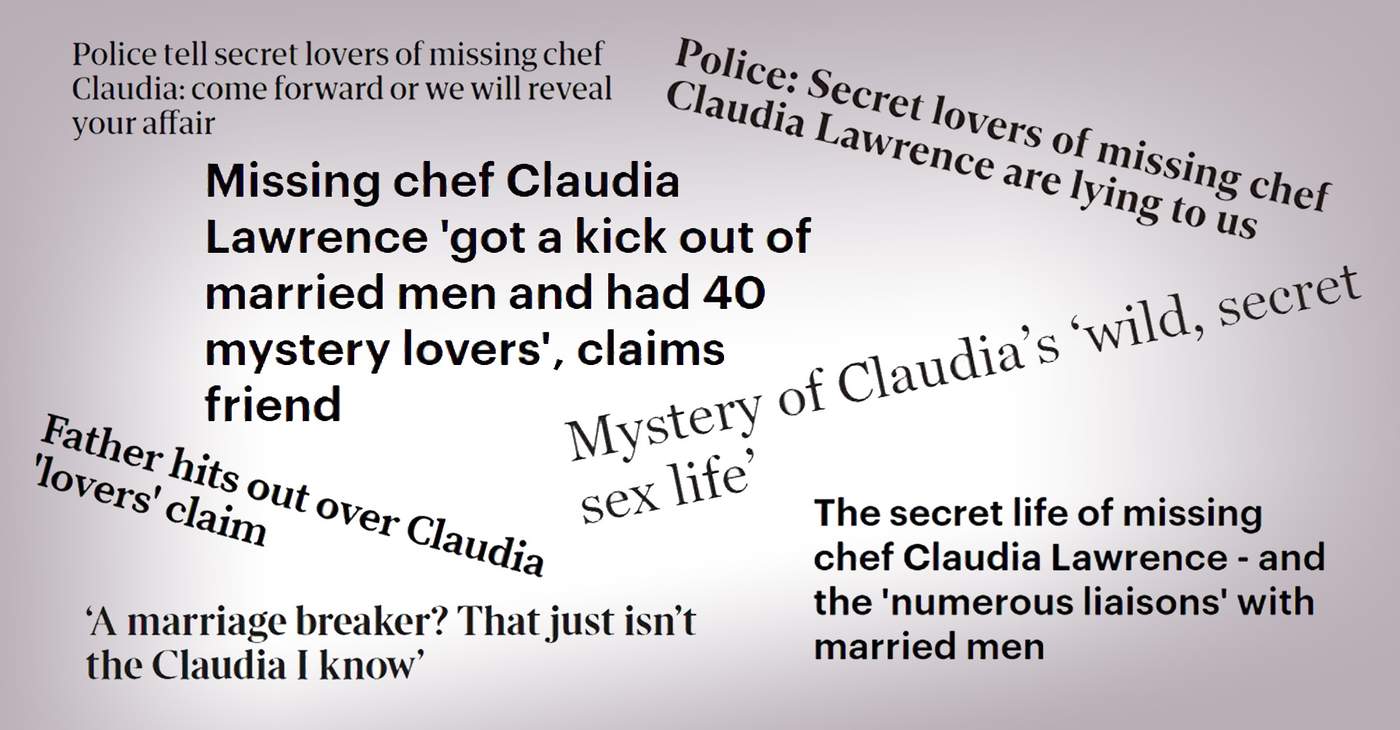

By June, the case had taken a different direction. Its lead detective told BBC Crimewatch that investigators were now focusing on allegations made about the chef’s love life.

“Who was Claudia going out with? Who was she seeing?” Mr Galloway asked viewers. “Who was her boyfriend? Who was showing her maybe some unhealthy interest?”

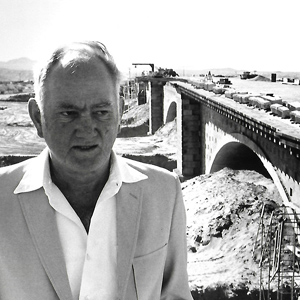

Former Det Supt Ray Galloway led the initial investigation

In a second appearance on the show he made more direct claims, describing Claudia’s relationships as “complex and mysterious” - words that immediately became the subject of tabloid headlines.

“It set the rumour mill whirring,” says former Met detective chief inspector Clive Driscoll.

Mr Driscoll, who is credited with finally securing justice for the family of Stephen Lawrence, has previously examined Claudia’s case as part of a documentary.

He believes Mr Galloway’s comments turned public opinion against her and had a detrimental effect on the investigation.

Clive Driscoll was the face of a 2018 documentary - Stephen: The Murder that Changed a Nation

“The way Ray Galloway went about it was wrong, he should have phrased it differently,” he says.

“It painted a picture that Claudia somehow deserved what happened to her. It had a big impact on how people viewed her and subsequently how the public responded to the investigation.”

Mr Galloway, who is no longer with the force, was contacted by the BBC about points raised in this article. He declined to comment.

The maxim “find out how a person lived and you will find out how they died” is in chapter one of the National College of Policing’s murder investigation manual.

It states that it is only in a minority of cases that there is no prior association between the offender and the victim; that understanding the lifestyle and routine of a victim is key to finding out why they died; and that the majority of women are killed by a partner or ex-partner.

Claudia was seen on CCTV leaving work at the University of York

The focus on Claudia’s love life was both a natural and legitimate line of inquiry. Mr Galloway would have been failing as senior investigating officer had he not pursued it.

Former police inspector Martin Holleran, now a senior lecturer for police studies at York St John University, said the detective was faced with a tough decision.

“It’s a huge balancing act. You need to put that information out because if you don’t you might not get the right people to come forward.

“But once it’s out there you don’t have any control over the slant the press will put on it.”

Mr Galloway’s public comments about Claudia’s “secret relationships” were indeed seized upon by journalists.

“Claudia’s sex life, her alleged affairs, were represented in the press as being of key relevance to her case and status as a victim,” says Dr Charlotte Barlow, criminology lecturer at Lancaster University.

“Some of the main phrases used to refer to her were things like ‘scarlet woman’ or ‘home-wrecker’ and it’s this kind of narrative and language which has underlying, highly gendered assumptions.”

Dr Barlow says such wording is only really used to describe female victims and represents them as somehow responsible for their fate.

“However, the blame and focus here should always be on the perpetrator, ensuring that they are held to account, and never on the victim.”

Dr Karen Shalev-Greene, director for the Centre for the Study of Missing Persons, says there is often an element of “victim hierarchy” in how the press portray missing people.

“The most ‘innocent’ victims get an almost angelic coverage while those with more ‘complex’ lives are portrayed differently, without a thought to the victim or the family.”

Police suspected that Claudia had several lovers over a number of years - not unusual for a single woman of her age who was actively dating.

But when coupled with the suggestion that some of them were married, she was seen as “the other woman”.

The picture painted of Claudia in the press was not one her friends recognised. “If this was a man, this kind of behaviour would not have been an issue,” says Suzy.

Jen defended Claudia when asked by the press about the chef’s love life

“There was a marked change when the salacious stories started,” adds Jen.

“They didn’t mention Claudia the great friend, the loving daughter, the chef who went to work even if she was on death’s door.

“She might have been seeing someone, she might have been going on dates we necessarily didn’t know about but really, it was a non-thing as far as we were concerned.

“She wasn’t exclusive with anyone at the time. She wasn’t married or had kids to look after, she was just living her life - and why not?”

The allegations about their daughter’s love life were a surprise to her parents.

Joan was furious and dismissed Mr Galloway’s comments. Peter thought them insensitive but conceded he wouldn’t have expected to know every detail of his daughter’s private life.

“It was obviously difficult to hear and of course the media just went crazy with it,” he says. “But she was a 35-year-old single woman, it would have been more unusual if she hadn’t [had relationships].”

North Yorkshire Police had started to consider jealousy and revenge as motives. A key focus was the Nag’s Head, where Claudia had met several men with whom she’d had relationships. Bed sheets were taken from the pub for examination and regulars were interviewed, to no avail.

Meanwhile, at the York Press, armchair detectives were calling the newsroom with their theories and reporters heard repeated rumours concerning the university’s Ron Cooke Hub, which was being built in 2009. They were further fuelled by claims Claudia had been involved with men in the building trade.

“With that building project there was a lot of concrete being put down and there was a suggestion she may have been dumped under there,” says Mike Laycock.

The investigation on the whole appeared to be hampered by a reluctant public wary of being implicated in what had been portrayed as a lurid scandal.

There were also a number of red herrings, including psychics who claimed they knew where Claudia was and a hoaxer who posted as her on Facebook.

“The challenge is that you have to get people to come forward with information,” reflects Mr Driscoll. “But that was hindered because of how the case was handled.”

With leads dwindling, the force scaled down the investigation in July 2010. The following February, Crimestoppers withdrew its £10,000 reward for information.

“It does haunt me,” Mr Galloway said in an interview at the time, describing how he had spent many restless nights thinking about the case.

“There is every potential that we have spoken to her killer.”

By the time Det Supt Dai Malyn had completed his review of the Claudia Lawrence case for North Yorkshire Police, he had reached a far blunter conclusion.

“I still strongly favour the theory that the person - or persons - responsible for Claudia’s disappearance was someone - or several people - who were close to her.

“It was either very well-planned or there was a huge element of luck to have got away with it, so far at least.

“In my view they have probably been helped by the fact that those closely associated with Claudia have withheld key information.”

The detective’s comments in 2016 spoke to the frustration of a case which had left his force with a black mark in its unsolved crimes column for years.

His team had spent two years unearthing new leads and theories - the most significant of which was considering the possibility that whatever happened to Claudia did so on 18 March and not the next day.

It is a theory supported by Clive Driscoll, who thinks it far more likely she came to harm overnight.

“It could have all gone horribly sour the moment Claudia finished that phone call with her mum. From the time she finished that conversation… is, in my mind, where the focus should lie.”

The alley search was carried out six years after Claudia vanished

Claudia’s house was forensically re-examined using techniques not available to the original team. This turned up new fingerprints and DNA that remain unidentified to this day.

Det Supt Malyn stressed the growing importance of the alley behind Claudia’s home and officers searched it on their hands and knees. He suggested if something had happened at the property overnight those responsible would have used the alley.

The review team discovered some used bleach and brown hair dye in Claudia’s bathroom and that her hair straighteners were missing

The review also unearthed additional CCTV images similar to that released by the original inquiry team of the man seen near Claudia’s home on the morning of 19 March.

The new footage was shot by the same camera the previous evening and appeared “to show the same man in the same place”, Det Supt Malyn said.

The man walks into Heworth Place and out of shot before reappearing about a minute later, stopping briefly while someone up ahead walks across the road.

North Yorkshire Police said he remains a key person to trace.

Finally, in 2014 - five years after Claudia disappeared - police made the first arrests.

A house in North Shields on Tyneside was searched and a pub in Acomb in York had its cellar dug up. For reasons that remain unknown, Claudia’s phone had been traced to that area in the weeks before she vanished.

A 59-year-old man was held on suspicion of murder and a 46-year-old man was held on suspicion of perverting the course of justice. Both were released later that year without charge.

The following year, hopes were again raised when four local men, who drank in the Nag’s Head, were arrested on suspicion of murder. Then in March 2016, the Crown Prosecution Service abandoned proceedings, citing a lack of evidence.

North Yorkshire Police said at the time the case had “ultimately been compromised by the reluctance of some, and refusal of others, to co-operate”.

The Nag’s Head, now under new management, was a key focus in the case

The final blow came in late 2018 when police announced that attempts to identify a suspect from DNA obtained from a cigarette butt in Claudia’s car had drawn a blank. It meant that the £1m inquiry had stalled again.

Despite thousands of names and statements being recorded, despite hundreds of interviews and searches, police still lacked that crucial piece of information. Det Supt Malyn’s disappointment was clear.

The North Shields house was searched by forensics officers

“I am sure that there are some people who know, or who have very strong suspicions about what happened to Claudia. For whatever reason they have either refused to come forward, or have been economical with the truth.

“I am left with the inescapable conclusion that this case could still be solved if only people were honest with us. The fact that they are not is agonising for Claudia’s family and they should be ashamed of themselves.”

Claudia’s case is now in a “reactive phase”, meaning it will only be reviewed if new information comes to light. Mr Driscoll - who cracked the Stephen Lawrence case after numerous police failures - believes the unsolved crime would benefit from an independent review, perhaps by a different force.

“With the utmost respect to North Yorkshire Police, the case could do with a fresh pair of eyes,” he says.

“It might mean they have to say, ‘listen, this is a bit embarrassing’, but at least it might provide some answers as to what has happened to this poor girl.”

The force’s reluctance to take part in interviews on the 10th anniversary of the case is a wasted opportunity for “one big push” to solve it, says Mr Holleran.

“Ten years on and loyalties change. People may struggle to live with the knowledge they possess and cracks may form.

“Anniversaries such as this are an ideal opportunity to bring people forward again and get Claudia’s name back in the public’s mind.”

Det Supt Dai Malyn led the review into Claudia’s case

The BBC asked North Yorkshire Police a series of questions about the points raised in this article on a number of occasions during its production.

In response, the force provided a statement from Det Supt Malyn which said his review was led by a “gold group” of experts from around the country that maximised “every opportunity” to establish what happened to Claudia.

He said detectives would continue to investigate any new information, adding: “North Yorkshire Police will never give up on Claudia and her family.”

The past decade has proved an agonising time for those close to Claudia.

Peter has gained comfort by helping others caught up in the aftermath of a loved one’s disappearance and has been appointed OBE for his work. He has successfully campaigned for Claudia’s Law, which allows families to manage a missing relative’s finances and property - including his daughter’s.

Claudia’s friendship group has fragmented as they wrestle with the inconceivable idea the killer could be known to them. For Suzy, it has been particularly hard - she has become withdrawn and finds social situations almost impossible.

“I have pushed people away. I suppose that way if I don’t get close to anyone they can’t leave me or disappear,” she says.

A mother’s instinct keeps Joan going. She refuses to believe her daughter is dead because she has “no cut-off feeling”.

“I get up in the morning and see what the weather is like. If it’s snowing, Claudia wouldn’t have liked it - she hated the cold. In the supermarket I see tulips, her favourite flowers.

“You have to keep going. If I stay in bed all day looking at four walls, what good will that do?

“I will not give up [hope]. One day I will find out what happened to my daughter.”