Parts of this story are reconstructed from trial testimony, evidence and publicly available records. It contains strong language throughout.

Four vehicles fly down a darkened, rain-soaked street. It’s summertime, nearly midnight in downtown Baltimore.

The lead car, a white Chevrolet, is driven by a 34-year-old man, his foot pressed to the pedal. On his tail are three unmarked police cars driven by members of the Gun Trace Task Force, a plainclothes gun recovery unit.

The chase started after the Chevrolet ran a red light. Pursuing the vehicle would be a violation of Baltimore Police Department policy, but the detectives suspect the man in the Chevy has guns, drugs, cash or all three.

“Might be able to get somethin’ dirty,” detective Daniel Hersl says excitedly.

“Light him up,” detective Jemell Rayam responds.

The pursuit proceeds to the sounds of revving engines and heavy rain pelting the windows - there are no sirens.

The Chevrolet blows through another red light. He almost makes it across the intersection when a Hyundai Sonata going through the green collides with the driver’s side of the Chevy, launching both cars up on to the pavement. The Chevy crumples into a motionless wreck.

“Shit!” exclaims detective Momodu Gondo from behind the wheel. “Damn.”

“Keep going,” responds his partner, Rayam. “I don’t know.”

“Shit!”

“I don’t know,” repeats Rayam. “I don’t know.”

Without stopping, the detectives radio back and forth between their cars.

“We ain’t look too crazy, did we?” asks Gondo. “They got cameras all up and down that shit.”

“I can get on the air and say I just got a report of an accident,” says Rayam.

“No, Wayne said - I wouldn’t say nothin’ yet,” responds Hersl.

Several blocks away, two of the three police vehicles pull to the side of the road and the officers confer. Gondo thinks he only had his lights on at the very beginning of the chase - maybe no one noticed them.

“That’s the thing with Wayne. He’s a little too much with this shit,” says Hersl. “These car chases. This is what happens.”

Eventually it strikes the officers that they never called for aid.

“How about we just go on scene and just act like, ‘Oh, is everything OK?’” asks Rayam.

“That dude unconscious, he ain’t sayin’ shit,” responds detective Marcus Taylor.

Listen to the Gun Trace Task Force before and after the car crash (WARNING - contains strong language)

Over half an hour after the crash, they’ve still done nothing. Hersl suggests they change their time cards to make it appear they stopped work hours earlier. Wayne Jenkins, the unit’s leader, stops to scope out the accident, but also does nothing to help.

“I wonder what was in that car,” says Hersl.

“I don’t care,” Jenkins snaps. “Go back to HQ.”

A year and a half later, in a federal courthouse in downtown Baltimore, a prosecutor switches off the audio recording from that night, captured on a FBI listening device hidden in Gondo’s police vehicle. On the witness stand sits Rayam, a tall, broad-shouldered man with a smooth pate. Instead of his police uniform, he wears bright orange prison garb.

Facing him from the defendants’ table are two of his former colleagues, Daniel Hersl and Marcus Taylor.

“None of us stopped to render aid or see if anyone was hurt,” Rayam tells the courtroom in a faltering voice. “We were foolish, I don’t know, we just didn’t… we just didn’t stop.”

In the case of United States versus Daniel Hersl and Marcus Taylor, the car accident is the least of the men’s legal worries. They are facing multiple counts of extortion, racketeering and fraud for their part in what prosecutors call a “perfect storm” of police officers gone rogue. Rayam, Gondo, Jenkins, as well as two other officers from the Gun Trace Task Force have already pleaded guilty.

When the prosecutor finishes his questions, Rayam seems to completely fall apart. He shields his eyes from the jury.

In an already exceptionally dramatic trial, it is a disorientating moment. As Rayam - a once-respected police detective, a college-educated father with a nice house in the suburbs - sobs silently on the witness stand, it is impossible not to wonder...

What happened to these police officers?

On the day of Aaron Anderson’s arrest, Detective David McDougall of the Harford County Sheriff’s Department rose around dawn and crept out of his house in rural Maryland before his family awoke. He drove south to meet his team in the rear car park of a Red Roof motel perched on a busy intersection in the suburbs of Baltimore.

McDougall pulled on a tactical vest, preparing for just “another day at the office”. But nothing about the arrest of Anderson went as expected.

As a part of his work on the county’s narcotics task force, McDougall had been watching the 27-year-old suspected heroin dealer for weeks.

David McDougall

He’d sat outside Anderson’s drab apartment complex in northwest Baltimore as he came and went. He'd also placed a GPS tracking device on the undercarriage of Anderson's Jeep Cherokee.

He’d observed surprisingly open drug sales at a strip mall, where Anderson was trailed by a small group of young men palming tiny plastic packets into the hands of drivers streaming in and out of the car park in full view of McDougall and his camera lens.

The very fact the arrest team was gathered at a motel that morning was the first surprise. Days earlier, they were ready to arrest Anderson at his apartment when he stopped going home. The GPS tracker on the Jeep was going to the Red Roof instead.

They snapped photos of Anderson and his girlfriend as they stood on the balcony talking on their phones. When it became clear the pair were not checking out anytime soon, McDougall rewrote his warrants for the motel.

On the morning of 19 October 2015, he and his team sat in the car park waiting for the door to room 207 to crack open.

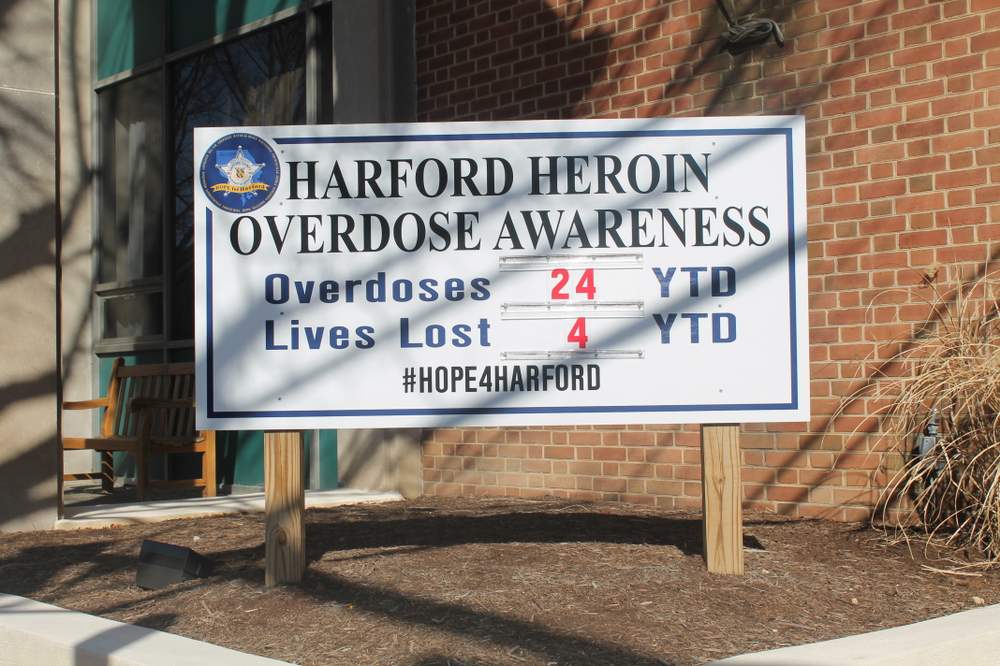

Anderson was the first in a series of dominoes McDougall hoped to topple. A major narcotics investigation concluded there were two Baltimore-based drug dealers supplying the bulk of the far more rural Harford County’s heroin: Anderson and a rival dealer named Antonio “Brill” Shropshire.

The two men had distinguished themselves in the eyes of law enforcement by peddling a particularly lethal product. In the last year, overdoses had skyrocketed in Harford County and McDougall believed as much as 80% were caused by heroin supplied by Anderson or Shropshire’s organisations. The deaths went as far back as 2011.

19-year-old Alyssa died of a heroin overdose in Harford County in 2011

And something had always bothered McDougall about the way the men operated, the openness of the drug dealing he had witnessed after weeks of surveillance. He likened it to a “fog” around the investigation.

“It’s right out in front of us and nothing's being done,” he recalls. “I'm like, ‘There's something wrong here.’”

Anderson finally emerged from the room a little after 11am. As he and his girlfriend walked towards the Jeep, McDougall and his men surrounded them.

With the pair in handcuffs, McDougall radioed to a second team positioned outside Anderson’s apartment, and confirmed that it was safe to go inside.

As the secondary team searched the apartment, McDougall sat Anderson in the back of a squad car and asked what he was doing at the Red Roof motel in the first place.

“He’s like, ‘Two guys kicked in my door while my girl was home, stole stuff from me, they had handguns, I didn’t feel safe,’” recalls McDougall. “As he tells me that I get a phone call.”

It was the team at Anderson’s apartment - it was trashed. There was a boot print on the front door, the lock shattered. Drawers were pulled out of dressers. There were no drugs, just some digital scales and roughly 10 different mobile phones. Someone had beaten the officers there.

Anderson’s girlfriend told McDougall that two weeks earlier, a man with a hoodie pulled tight around his face ran into her bedroom, pointed a gun at her and threatened to kill her. He took jewellery, $10,000 in cash, a Rolex watch and a gun from their dresser. The second masked man headed for the kitchen. Anderson eventually revealed that 800g of heroin was stolen that day. Rather than call the police, the pair fled to the motel.

The same strange fog crept over McDougall. Something about the description of the way the apartment was tossed seemed oddly familiar.

The arrest team was wrapping up loose ends when one of the officers called out to McDougall. He was underneath Anderson’s Jeep, pulling off the magnetic GPS tracker McDougall had placed there weeks earlier.

“Hey Dave,” the detective said. “Do you have two on here? There’s another one.”

About eight inches away from McDougall’s GPS tracker was a second device. He was stunned.

McDougall knew for a fact no other law enforcement agency was investigating Anderson. In order to avoid stepping on one another’s toes, agencies enter the names and personal information of their investigative targets into what’s called a “deconfliction database”.

It’s a tool that allows local and federal agencies to see what investigations are already under way. McDougall had listed Anderson in deconfliction databases from “here to California” and nothing popped up.

“Right away it was kind of like, ‘Whoa, what's going on here?’” says McDougall. “Whose tracker is this?”

As soon as he returned to headquarters, McDougall wrote a subpoena for the company that manufactured the mystery tracker, asking them to identify the owner.

Within days he had a name: John Clewell. A driver’s licence photo showed a bald, moustached man in his 30s. When McDougall put the name into the Maryland court database to look for a criminal history, dozens of cases came up.

But it didn’t list Clewell as the defendant. Rather, it showed Clewell as a witness for the government. He was a cop. A detective with the Baltimore Police Department’s Gun Trace Task Force.

McDougall formed a rough theory about what had happened - a Baltimore police officer, using the tracker, waited until Anderson’s vehicle was far away from his home, then used the opportunity to rob the apartment. The home invasion had some of the hallmarks of a police raid - the kicked-in door, the methodically tossed apartment. McDougall picked up the phone and called the FBI.

“I thought it was limited to maybe one or two guys,” he says. “That was going to be the end of the story.”

McDougall had no idea that what he had uncovered would lead to the arrest and indictment of eight police officers, nor that it would implicate at least a dozen more and point to a mole within the local prosecutor's office.

He had no inkling that it would unravel hundreds, and potentially thousands of criminal investigations, and free men from prison who’d sworn from the very beginning that they were framed, robbed, or both. It would one day explain the murder of a young father in front of his family, and raise endless questions about the death of a homicide detective, shot dead the day before he was supposed to testify against the rogue officers.

In the autumn of 2015, all of that was still to come.

Here’s what the public was led to believe about the Gun Trace Task Force, before the FBI arrested almost every member of the squad:

That in a city still reeling from the civil unrest that followed the 2015 death of Freddie Gray in police custody, the GTTF was a bright spot in a department under a dark cloud. The 25-year-old African-American man’s death after a ride in a police transport ignited a build up of decades of tension between Baltimore's black residents and the police, touching off days of demonstrations, including looting and violence.

That while the homicide rate was on a historic rise, this elite, eight-officer team was getting guns off the streets at an astonishing rate - their supervising lieutenant praised “a work ethic that is beyond reproach” that resulted in 110 arrests and 132 guns confiscated in a 10-month period.

That the GTTF’s leader, a former Marine and amateur MMA fighter named Sergeant Wayne Jenkins, was a hero who’d plunged into a violent crowd during the unrest to rescue injured officers, an act of bravery that earned him a departmental Bronze Star.

But when the sun came up on 1 March 2017, the city awoke to a vastly different reality.

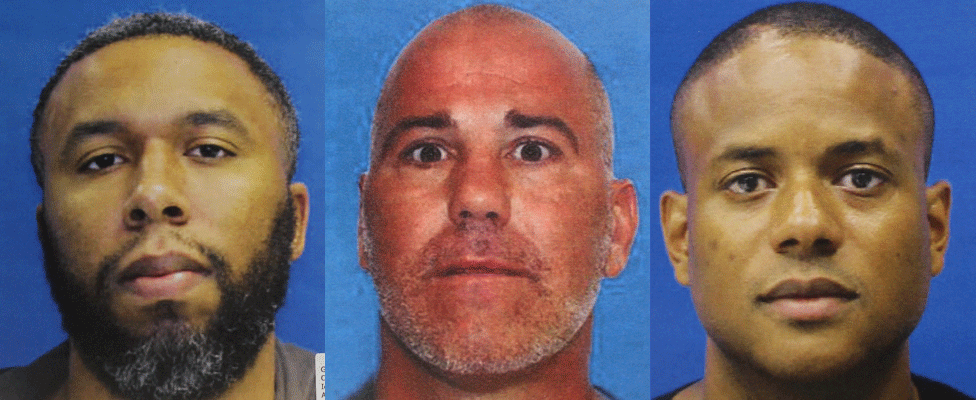

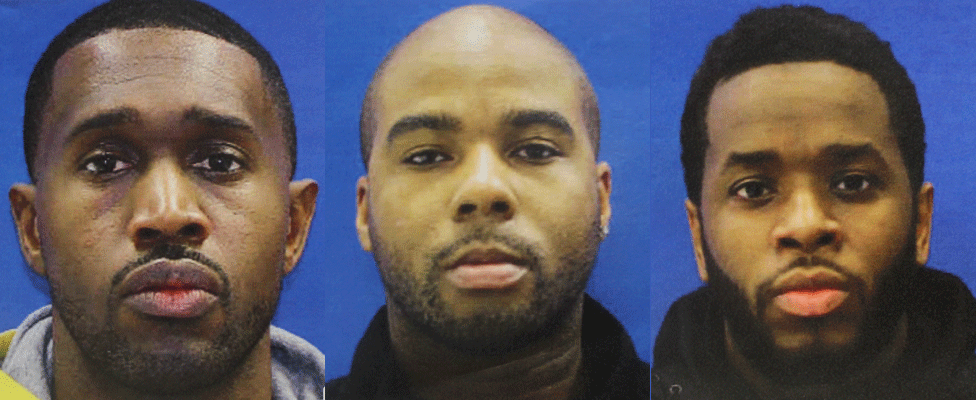

Seven officers were arrested and indicted for racketeering, extortion and fraud: Sergeant Jenkins; Detective Daniel Hersl, a 17-year veteran of the force; longtime partners Detectives Momodu Gondo and Jemell Rayam; and Detectives Maurice Ward, Evodio Hendrix and Marcus Taylor. Only one member - oddly enough, John Clewell, the man whose name triggered the entire investigation - escaped indictment. The FBI found he was never a part of the criminal enterprise.

“They were involved in a pernicious conspiracy scheme that included abuse of power,” the US Attorney for Maryland told reporters that day. Police commissioner Kevin Davis, who’d once praised the men’s work, now likened them to 1930s-style gangsters.

“It’s disgusting,” he said.

The public soon learned that the GTTF stole from drug dealers, but also from a homeless man, a car salesman, a construction worker and many others. The victims were overwhelmingly African-American.

Evodio Hendrix, Daniel Hersl, Jemell Rayam

That they received hundreds of hours of overtime, when they were actually at the bar or on the beach, from a city that struggles to keep the heat working in its schools.

Maurice Ward, Marcus Taylor, Momodu Gondo

That during the unrest, Jenkins was stealing garbage bags of opiates from pharmacies, and that he also stole and re-sold heroin, Ecstasy, crack and cocaine.

That he planted drugs on innocent people, and was slowly building up the courage and the arsenal to commit fully-fledged burglaries.

Wayne Jenkins

“They owned the city,” shrugged one witness who admitted to acting as the fence for Jenkins’ stolen goods. “It was a front for a criminal enterprise.”

The revelations crescendoed in an explosive three-week trial in federal court which drew back the curtain on a phenomenon extensively explored by Hollywood but rarely witnessed in real life: the inner workings of a police unit gone rogue, and the path of human destruction left behind it.

In a city just coming off the highest murder rate in its recorded history, some residents wonder how much of that violence can be attributed to a citizenry that felt abandoned by its police force.

“Their behaviour had to have contributed to the uptick in violence, there’s no way it didn’t,” says one retired BPD detective. “The police department thinks they can kind of push right past it.”

Even after the arrests, victims of the GTTF say they don’t believe that they are safe, and that there are members of the Baltimore Police Department who have yet to be exposed.

“I was a black man with a past history,” one victim said. “That’s why I’m so bitter and angry about this… Y’all put so many people away for things I know they didn’t do."

On a hot July afternoon in 2016, detective Momodu Gondo dialled his new boss’s mobile from the front seat of an unmarked police sedan. Sitting silently behind him was a professorial man with a trim beard and glasses, his hands cuffed behind him.

“What’s up, G?” Sergeant Wayne Jenkins answered.

“We got the package,” Gondo said.

“Is he in the car with you?” Jenkins asked. “Did you tell him anything at all?”

“No.”

“Alright,” Jenkins said. “When I get there… introduce me as the US attorney.”

“I got you.”

Listen to Jenkins and Gondo planning during Ronald Hamilton's arrest

A short while earlier, Gondo, Rayam and Hersl had been following Ronald Hamilton and his wife up and down the aisles of a Home Depot as the couple shopped for window blinds. When the Hamiltons left the car park in their pick-up truck, the detectives followed in three separate, unmarked police vehicles. Rayam hit the lights and sirens, and Hamilton pulled to the side of the road.

The GTTF had had their eyes on the Hamiltons for some time. An informant told Rayam that Hamilton was a high-level drug dealer. After only two years out of federal prison on a previous drugs conviction, Hamilton moved his family into a resplendent, seven-bedroom house on a winding dead-end street in the Baltimore suburbs, complete with a manicured lawn and a swimming pool. If they raided the place, the informant said, they’d find it stuffed with guns, drugs and cash.

The officers drove the Hamiltons to a dilapidated building behind the Baltimore police academy, nicknamed “The Barn”. Inside, they grilled the couple about Hamilton’s supposed drug dealing, while he insisted that the only things he sold were used cars.

When Jenkins arrived, he told Hamilton he observed him on three separate occasions making drug deals. Hamilton said it was a lie. But he did tell them he had cash in his home.

Though they had no evidence the Hamiltons had done anything illegal, Rayam stuffed the couple back into a car and led Gondo, Jenkins and Hersl on a high-speed convoy towards the mansion in the suburbs. As Rayam sped through the streets, Hamilton whispered to his wife.

“Just don’t say nothing,” he said. “They trying to rob me.”

It had only been a month since Jenkins became the new head of the Gun Trace Task Force. Detective Gondo had been on the GTTF since 2010 and knew plenty about Jenkins - that he was “protected”, somebody who had “pull” from on high. He knew less about some of the other detectives Jenkins brought over from his former Special Enforcement Section unit - Ward, Hendrix and Taylor, and from the eastern district, Hersl.

But Gondo said Jenkins made it perfectly clear to him who his new team members were.

“If money is taken, they’ll be with it,” Gondo remembered Jenkins telling him. “They’ll keep their mouth shut.”

For Gondo, that meant business as usual.

Gondo grew up in a rough part of north-east Baltimore, and though he joined the police academy in 2005, he did not sever ties to Glen Kyle Wells, a lifelong friend and heroin dealer.

They spent lavishly on nights out, ordering bottle service at local clubs. Gondo also formed a friendship with Wells’ heroin connection, Antonio Shropshire. Gondo didn’t hide his relationship with Wells from other officers and regarded Wells as a brother.

“We through thick and thin, man,” Gondo told Wells at one point. “It’s always going to be like that.”

When Wells came to Gondo and told him that some of his business associates wanted to rob and murder a rival dealer named Aaron Anderson, it was Gondo who proposed that he and Rayam assist, and use the GPS trackers to avoid a violent confrontation. They borrowed the tracker from Clewell, and it was Gondo who sat outside as the lookout, listening to a police scanner while Rayam and Wells pulled on masks and ransacked the apartment. They split the heroin and the $10,000, and Gondo gave the gun to Wells.

When Wells felt he was being tailed by police, Gondo gave him precise details about the location of other officers in the area. When Shropshire found a GPS tracker underneath his car, he called Gondo for help.

So naturally, Gondo was furious when Wells showed Gondo text messages he was receiving from a mysterious number, asking to buy drugs. Gondo looked at the awkward use of slang and was certain it was his new boss, Wayne Jenkins, trying to set Wells up.

“That’s my friend,” Gondo fumed privately. “There’s plenty of other people out here you can target.”

Before Jenkins crossed that line, Gondo enjoyed the copious overtime and short working hours. Instead of putting together complicated investigations and targeted raids, Jenkins preferred “door pops” - speeding towards large groups of young black men on street corners and throwing open the doors. Whoever ran got chased, arrested and, occasionally, robbed. They could do as many as 50 door pops in a single night and as soon as they found a gun, they went home.

Bodycam footage of a GTTF arrest

Jenkins didn’t care if his men built trust or big cases - as long as they were making gun arrests, they worked a few hours a day, sometimes less, and got paid for far more.

When the detectives arrived at the Hamiltons’ home on that July evening, Gondo, Rayam, Jenkins and Hersl went inside for what the squad called a “sneak and peek” - an improper, warrantless search of a home to see what was inside.

In the bedroom, they found $50,000 cash in a heat-sealed plastic bag. Gondo went into a closet and found another bag containing $20,000.

Later, accounts varied on who actually decided to take it - Rayam said it was Jenkins, Gondo said it was Rayam.

Typically, Gondo didn’t like to steal money if there was no other evidence discovered in the house. His logic went that a drug dealer is unlikely to complain about missing drugs and money if it only made his operation look bigger. But the Hamiltons’ house was clean.

Ultimately he decided that didn't matter.

“Give it back to me so I can take one stack out of there," Gondo said.

The men went back outside and waited for the state police to give the veneer of a legitimate law enforcement operation. But after hours of combing the home and questioning the Hamiltons, the officers came up empty. The state police took possession of the $50,000 in the heat-sealed bag, but there was no reason to charge the Hamiltons with any crime. Rayam unhandcuffed them, handed them a business card and headed for the door.

As Gondo was getting back into his car, he saw Ronald Hamilton run back out of the house, a distraught expression on his face.

“You robbed me,” Hamilton called after the officers as they drove away.

Over celebratory drinks afterwards, Gondo confronted Jenkins about the text messages on his friend Wells’ behalf. Jenkins agreed to back off. They drank together, and Jenkins advised his men not to “get greedy”.

It’s hard to find another word to describe the summer that followed.

Next came the high-speed pursuit of Dennis Armstrong, who sent snowballs of cocaine sailing out of his van windows as he fled the GTTF. When they finally stopped him, the officers found $8,000 in a glove box. Only $2,800 made it back to the police station as evidence.

A month after that, the GTTF stopped a wiry homeless man named Sergio Summerville as he was leaving a storage locker where he kept all his belongings. The officers pilfered $2,000 from the sock where Summerville stashed his money from drug sales without bothering to arrest him.

In a seemingly unrelated incident in July, a 31-year-old man named Davon Robinson was shot multiple times in front of his horrified girlfriend and their young daughter. The shooter jumped into a waiting vehicle and disappeared. Robinson was declared dead at the scene.

At the time, the death generated scant media attention - just another murder at the height of a bloody summer in Baltimore.

As autumn drew closer, something started bothering Gondo. There was the night that he could have sworn a car near his home was watching him. Next came the rumours. Something about a federal investigation. Something about a wiretap.

Eventually he confided in Rayam as they sat together in Gondo’s police car. By the end of the conversation, they’d both decided there was nothing to worry about.

“What case?” Gondo muttered loud enough that an FBI listening device planted in the car picked it up. “It’s no Pablo Escobar. It’s police.”

As the video begins, the mobile phone camera shakes and shadowy figures hover around the frame. A gloomy basement with a concrete floor comes into focus, children’s bicycles piled on top of one another, a washer and dryer pushed against a wall. In the middle of the floor lies a battered safe.

Two men’s figures stand over it, one with a pry bar wedged under the lock, the second with a ram.

“Hey Sarge!” one of the men calls. “Come downstairs right quick. They about to get it open.”

Within seconds, the lock on the safe cracks. It’s dark inside and the camera loses focus. When a torch snaps on, it reveals that the safe is filled with bundle after rubber-banded bundle of cash.

“Oh shit,” one of the men says.

“Stop right now,” snaps a third voice, swearing. “Nobody touch it.”

The video was intended to document the successful investigative handiwork of Jenkins, Ward, Hendrix and Taylor.

It was, in fact, an encore performance.

The video didn’t show the first time they broke open the safe, or that when they did, it was twice as full. It didn’t capture Jenkins strolling up the basement stairs and out of the home carrying two kilos of cocaine and a bag filled with cash. When he came back down, the officers re-closed the safe door, and re-enacted the moment of discovery with Taylor’s phone recording.

“We’re calling the feds,” Jenkins proclaims for the camera. “No one's touching this money.”

The basement belonged to Oreese Stevenson, a man with a long criminal history dating back to the mid-1990s. But ensnaring Stevenson was pure dumb luck, according to Ward. Jenkins had been using one of his favourite tactics - stopping any man over the age of 18 wearing a backpack.

When Jenkins, Ward, Hendrix and Taylor saw a man with a backpack climb inside Stevenson’s van, Jenkins pulled up the one-way street where Stevenson was parked the wrong way, and the officers jumped out. The backpack was stuffed with cash, and an old oatmeal box in the backseat contained a half-kilo of cocaine.

According to Ward, Jenkins became “obsessed” with Stevenson after his arrest, and listened to Stevenson’s jail calls to his wife. As they talked, the couple realised what had happened, that $100,000 had gone missing from the safe, that their watches had disappeared. Stevenson was livid. He told his wife to find him a good lawyer.

After hearing this, Ward said Jenkins decided to write a letter in neat handwriting from an imaginary, pregnant mistress to drive a wedge between the couple. The officers drove to Stevenson’s house and dropped it inside the door.

It didn’t work. The Stevensons hired Ivan Bates, a defence lawyer who knew the sergeant well.

“It had gotten to the point with Sergeant Jenkins and that crew, the constitution didn’t even apply,” says Bates. “They were just going to grab you.”

Bates declared his intention to run for Baltimore City State’s Attorney several months after the officers were indicted, and has placed the case at the centre of his campaign against the incumbent, Marilyn Mosby. But he says his history with Jenkins far predates a desire for the office.

In 2010, he took the case of a distraught young couple charged with slew of gun and narcotics possession offences. The officer who made the arrest, Jenkins, made an odd omission in his probable cause statement, which he submitted for a warrant at 4:30am.

According to the wife, Jenkins tried to barge into the house hours earlier, without a warrant, prompting her to press a silent alarm on her keychain.

When Bates showed the prosecutor the report from the alarm company, which torpedoed Jenkins’ timeline of events, he says the state dropped the case (the case predates Mosby’s administration and her office did not comment on the outcome). To Bates, the case was a huge red flag.

“It was such a brazen lie,” he says. “If they lied about this, what else have they lied about?”

Ivan Bates: 'There was nobody who had their back'

Bates says he noticed a pattern. Jenkins liked to arrest people on the street and find a way to go back to their houses. Once they got into the house, his clients - who were overwhelmingly young black men - kept telling him the officers stole money, drugs, jewellery. Because they were charged with crimes, the victims were ignored when they complained.

After the GTTF robbed Shawn Whiting of $16,000 in cash, spiriting away two pairs of high-end shoes and video games for his children, he wrote multiple letters of complaint from his prison cell. Internal Affairs told him he lacked sufficient evidence.

“This is what I’ve been saying since 2014,” says Whiting, who was able to withdraw his guilty plea and leave prison after the officers were indicted. “What you do in the dark come to light sometimes.”

Shawn Whiting

Although they were lauded for their arrest numbers, it was common for the cases to get dropped - a BBC analysis found under Jenkins, roughly half of their cases were never prosecuted.

Bates was able to get Stevenson’s charges dropped after he showed that Jenkins violated Stevenson’s constitutional rights during the initial stop. Bates says of the 20 cases he took with GTTF officers, 17 were dropped due to similar violations.

Nevertheless, an encounter with the GTTF could still have life-altering consequences. In 2016, Jenkins and his men pulled over 28-year-old Andre Crowder Jr and charged him with gun possession.

The case against Crowder was dropped after the officers were indicted. But in the three days he was locked up after his arrest, he learned his three-year-old son Ahmeer had contracted a serious case of pneumonia. As soon as he bailed out, Crowder went straight to the hospital and says he was only in the room for 30 minutes before machines started beeping and the room filled with doctors. Eventually someone emerged from the operating room to deliver terrible news. At the same time he was fighting the case, Crowder had to bury his son.

“I just wish that I can get the time that they took from me,” says Crowder. “I just wish that I could get that back.”

Listen to Andre Crowder talk about what the GTTF took from him

It wasn’t just defendants and their lawyers who raised the alarm early about Jenkins or his officers. Members of the Baltimore Police Department, the Baltimore City State's Attorney’s office, and city judges flagged the officers for lying - but it never seemed to be enough to derail their careers.

In the state of Maryland, the contents of police officers’ Internal Affairs files are protected by law. However, after the GTTF indictments, fragments of the files began leaking to journalists.

For example, in 2009, a motorist accused Jemell Rayam, along with another officer, of stealing $11,000 from him. According to the Internal Affairs file, Rayam pretended that he’d never met the other officer, until investigators pulled records showing that Rayam called his phone almost every day. Rayam later admitted the two were close friends, and on the stand in 2018, he admitted he took the money.

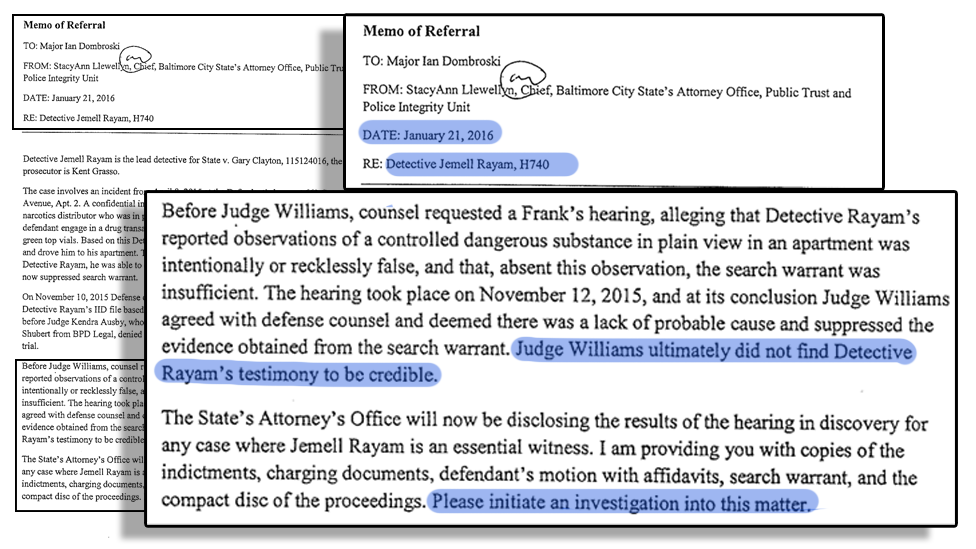

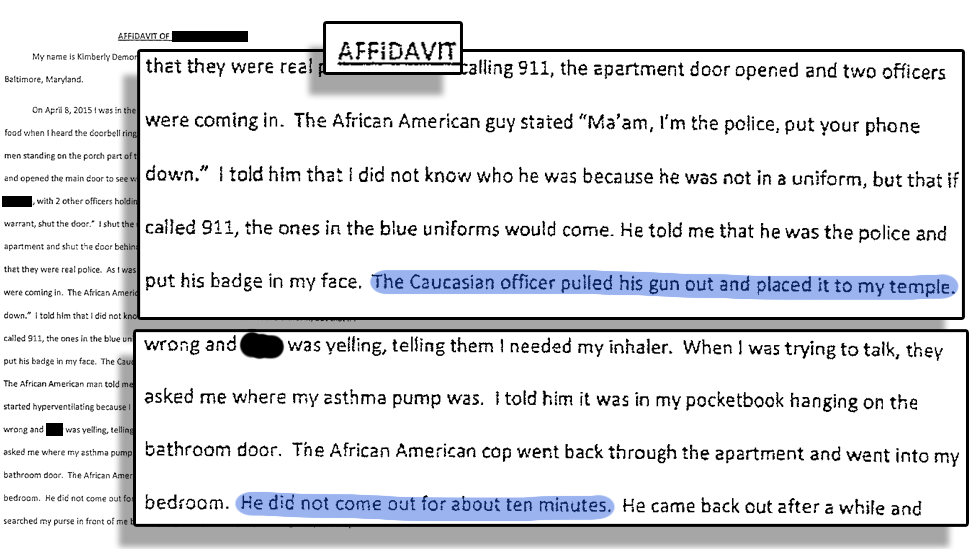

In November 2015, a woman complained to Internal Affairs that members of the GTTF held her at gunpoint to stop her from dialling 911. A leaked internal memo shows that the head of the Baltimore City State’s Attorney’s police integrity unit referred the case to Internal Affairs, requesting an investigation and pointing out that a judge ruled Rayam’s account of what happened “intentionally or recklessly false”.

Internal memo on Rayam's "intentionally or recklessly false" testimony

In 2014, an assistant state’s attorney named Molly Webb told “anybody that would listen” that Jenkins was untrustworthy.

It stemmed from the traffic stop of a man named Walter Price. According to the police report, Jenkins and other officers found seven grams of cocaine tucked into the visor of Price’s van.

But Webb says she was floored by the inconsistencies between a closed circuit video of the incident and the probable cause statement, written by a subordinate officer of Jenkins’. She dropped the case and says she notified her superiors. An Internal Affairs investigation into the incident sustained a charge of “failure to supervise” against Jenkins.

During this process, Webb says Jenkins sent her a lengthy text message she found frightening.

“States attorneys are informing me that you believe I’m a dirty cop that should be fired,” a text from a number associated with Jenkins' family from May 2015 reads. “It’s slander and hurtful to me what is being said. This is not a promise, nor is it a threat to you in anyway shape or form this is just hurting me and my reputation.”

At the same time, multiple defence lawyers have complained about getting access to Internal Affairs files from the Baltimore Police Department and the State’s Attorney’s Office, and asked why officers with problematic histories were still allowed to testify.

Through statements provided to the BBC, a spokeswoman for Mosby strongly disagreed that their office failed to readily disclose Internal Affairs files when required, and wrote that they “started providing an additional disclosure on Rayam” to defence lawyers after a 2015 complaint.

“We made disclosures in every case in which credibility was an issue,” she wrote.

“We did not have knowledge of anything with the IA files that would suggest that a larger criminal conspiracy was afoot.”

Mosby’s office also pointed out that before the officers’ indictments, the Baltimore Police Department did not regularly provide them with updates on Internal Affairs investigations.

Under a new agreement, they now receive a report on Internal Affairs complaints every week and a monthly list of suspensions.

A spokesman for the Baltimore Police Department called it “revisionist history” to think the files could have predicted the GTTF’s misconduct.

In June 2016, Jenkins took over the GTTF, giving him citywide jurisdiction, and brought several officers along with him who had internally documented problems with money and truth-telling. Bates, who thought Jenkins would be permanently sidelined by the outcome of the Price case, was dismayed.

“It’s sort of almost like a bad horror movie,” says Bates. “Every time you kill the villain, it comes back to life.”

The first of March, 2017, should have been a good day for Sergeant Wayne Jenkins.

He was up for a promotion - a big one. The vetting process was already under way, but there was just one tiny problem. To obtain the rank of lieutenant, he could not have any open or pending Internal Affairs complaints against him.

The open case Jenkins had was relatively small - a department car had been damaged and he needed to clear up how it had happened. An appointment was set with Internal Affairs officers and Jenkins called in the entire squad to vouch for him: Hersl, Gondo, Ward, Taylor and Hendrix.

One by one the men arrived to the squat brick building. They hit the buzzer to enter the lobby, where - per standard Internal Affairs procedures - they were directed to check their guns into tiny, post office box-like lockers. Each officer took the elevator to the command investigation unit on the second floor.

As the elevator doors slid open, the officers met the stony-faced gazes of a FBI Swat team. It was a trap. The agents had seven sets of handcuffs ready.

Jenkins had been warned multiple times that this could happen - first by a fellow officer, then from a contact in the state’s attorney’s office. Not long after the Stevenson case was dismissed, Jenkins took a 90-day leave of absence to help care for his newborn son.

But when he returned three months later, it seemed to the members of his squad that he was back to his old tricks.

Ward and Hendrix said Jenkins started reminiscing about the Stevenson case, and wondering if they couldn’t go back to his house again.

He told the officers he wanted to go looking for “monsters” - anyone with a lot of drugs and cash.

Hendrix thought Jenkins meant in a police capacity - until Jenkins opened up the rear doors of his police issued van to show them two large black duffel bags.

In the first, a green-headed sledgehammer, an 18-inch black-bladed machete, a four-pronged grappling hook, heavy-duty bolt cutters, various knives and pry bars, and an axe. In the second, an array of black clothing, black shoes, black gloves, a set of binoculars, ski masks and ski goggles, and two sneering, full-face masks that looked like characters from Alien.

“Once I seen all that, I came to the conclusion he was talking about robbing him,” said Hendrix.

After the arrest at Internal Affairs, the FBI executed search warrants on all seven officers’ homes and vehicles. In Jenkins’ van they found the two duffel bags, and in the driver’s side door, a set of well-worn brass knuckles.

That night, the entire squad slept in the Howard County Detention Center, 20 minutes south of the city. Some of them compared stories and vowed not to crack under pressure from the feds. But as days became weeks and then months, one by one the officers took plea deals.

Ward and Hendrix were the first, then Rayam and two days later, his old partner Gondo. Jenkins held out the longest, pleading guilty just weeks away from the start of the trial.

As the former colleagues started to turn on one another, investigators gathered enough new information to charge Jenkins’ predecessor, former GTTF officer-in-charge Thomas Allers, with racketeering and robbery.

The indictment detailed not only years of robberies committed with Gondo and Rayam, but a tragic connection to the death of Davon Robinson.

Two months before he was murdered, Robinson was arrested by Rayam, Gondo, Hersl and Allers for a slew of handgun possession charges. The 31-year-old had been in court for his arraignment the morning he was shot.

The alleged shooter, a 25-year-old man known by the street name “Sticky”, was arrested 20 days later. The mother of Robinson’s children told the FBI that back when Robinson was arrested by the GTTF, the officers stole $10,000 in cash, money that Robinson desperately needed to repay a debt. When he couldn’t, she says, he was murdered. (The BBC was unable to reach members of Robinson’s family.)

Allers pleaded guilty on 6 December 2017.

As the trial date grew closer, the public learned of yet another death connected to the GTTF.

On 15 November 2017, Baltimore homicide detective Sean Suiter went to the site of a triple murder he was investigating and was shot to death in broad daylight.

The weapon used was his own. There were three shots fired, and the description of the suspect was vague - an African-American male in a black and white coat who left no DNA and no fingerprints.

Police locked down the neighbourhood around the site for five days, an action the ACLU called “constitutionally suspect”, as they combed the area for clues.

A memorial where Suiter was found

Police commissioner Davis revealed that the day after his death, Suiter was scheduled to testify in front of a grand jury about his time working with Jenkins, Ward and Gondo.

Davis denied that Suiter himself was under investigation, calling him a “stellar detective, great friend, loving husband and dedicated father”.

The killing remains unsolved.

On the first day of the highly anticipated Gun Trace Task Force trial, former detective Hersl emerged from a wooden door at the back of Judge Catherine Blake’s courtroom, a US Marshal by his side, dressed in khakis and a navy blazer. He nodded to his parents and siblings, seated in a row near the top of the stadium-style seating gallery. Marcus Taylor followed in a navy coat and tie, with a small wave to his parents and extended family. Both men had been incarcerated since the day of their arrest.

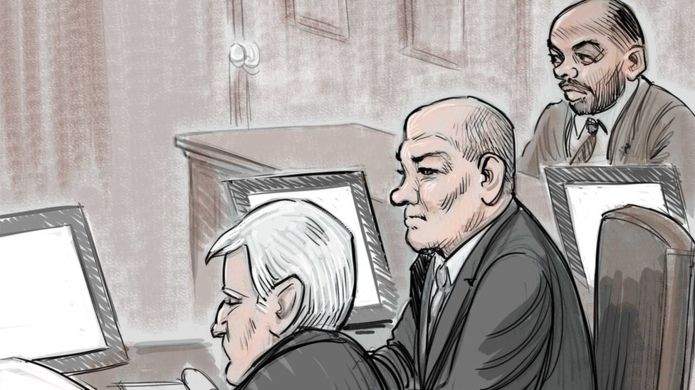

Hersl (centre) and Taylor (right) in court. Court sketch by Tom Chalkley

The government was represented by two over six-foot-tall assistant US attorneys, Leo Wise and Derek Hines, dubbed the “Twin Towers of Justice” as much for their stature as for their rigid, methodical style in court.

“The police officers in this case were entrusted with these,” Wise told the jury, holding the men’s badges and guns aloft. “They can be used for good. They can be used for evil.”

The first witness was former detective Maurice Ward. He entered in a bright green prison shirt, loose pants and rubber shoes, his hair and beard overgrown. As he waited to be sworn in, his bleary eyes scanned the audience for a familiar face. He did not appear to find one.

Over the course of two days, Ward walked the jury through years of robbery incidents going back to 2009, ones committed with Taylor, Hendrix and Jenkins when they were on a narcotics squad together, and ones committed with Hersl, Gondo and Rayam when they all joined the GTTF.

Ward explained the door-pops and the profiling. He said that Jenkins advised them to carry BB guns to plant if they ever shot an unarmed person. After the Stevenson robbery, Ward claimed he scattered the cash in a field behind his house, too scared of getting caught to spend or save it.

“You don’t want to be the one in the squad saying, ‘I’m not with that,’” he said. “You don’t want to be blackballed.”

The former officers testified in the same order in which they had pleaded guilty. Day after day they confessed to their crimes, and clashed with defence lawyers who tried to undermine their credibility.

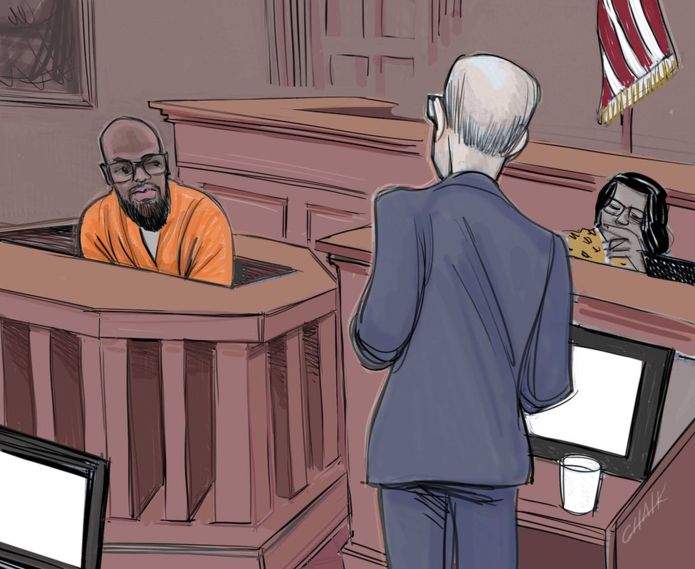

Gondo on the stand. Court sketch by Tom Chalkley

“You lied on at least 13 probable cause statements,” said William Purpura, Hersl’s lawyer, as he cross-examined Rayam.

“I totally understand my faults, sir.”

“You lied to juries, juries like this one,” Purpura continued. “You stole money. You stole narcotics. You stole guns… You can’t stop lying.”

“I’m not lying now,” Rayam said. “It’s never too late to do the right thing.”

The jury heard from eight robbery victims. Shawn Whiting displayed the letters he wrote in prison. Oreese Stevenson, who had to be subpoenaed to get him to show up for court, testified tersely about his experience. Ronald Hamilton told the story of his long night with the GTTF. For his final question, Wise approached him with a watch in a plastic evidence bag - Hamilton identified it as a Breitling watch that went missing from his bedroom during the raid.

The defence lawyers went after Hamilton particularly hard. They showed the courtroom how much money he lost gambling each year, they put up photos of his home and demanded to know how he could afford such a place. As Taylor’s lawyer ticked through a series of photos of the finished basement and the gleaming kitchen countertops, Hamilton snapped.

“They came in my house and destroyed my life. My kids are scared to come in the house, I’m getting divorced because of this,” he yelled, swearing. “This right here destroyed my whole family!”

Judge Blake instructed the jury to disregard his outburst, though it seemed like an impossible request.

The following day, like a man stepping out from behind the curtain in Oz, a 51-year-old bail bondsman named Donald Stepp took the stand. Nattily dressed in a grey suit and rectangular glasses, Stepp explained matter-of-factly that in addition to being a co-founder of Double D Bail Bonds, he was also a cocaine dealer now facing the possibility of life in prison.

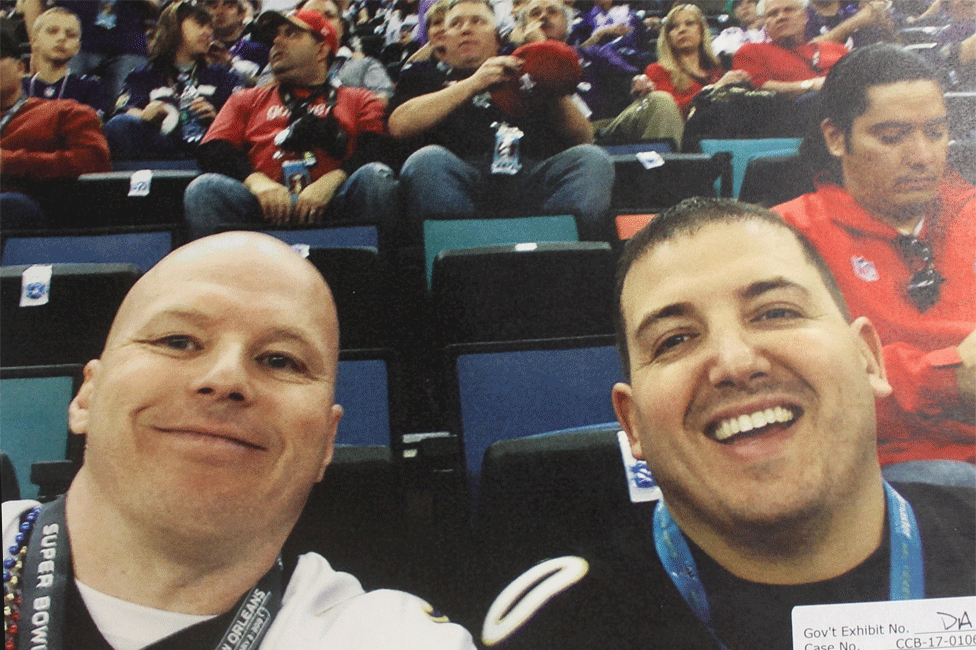

Stepp had known the Jenkins family for 40 years, and met Wayne at a cops’ card game. They became friends. They partied together at strip clubs with Stepp’s Dominican cocaine source. When the Baltimore Ravens went to the Super Bowl in 2013, they travelled to the game in New Orleans together.

Stepp and Jenkins at the Super Bowl

At some point, Jenkins asked Stepp if he’d be willing to help re-sell stolen drugs.

“I thought it was a winner,” said Stepp. “It was greed.”

Jenkins would deliver large quantities of narcotics on an almost nightly basis to a shed Stepp left unlocked. Stepp was most interested in cocaine, but said Jenkins left every conceivable type of drug, from crack cocaine to Ecstasy to heroin.

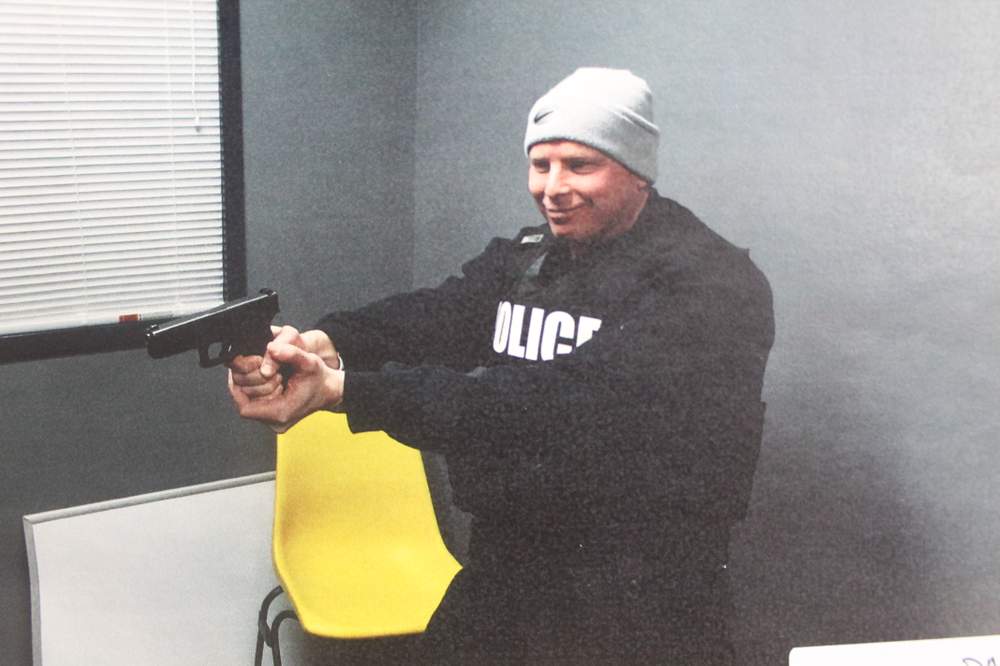

At one point, Hines pulled up Stepp’s Amazon purchase history which included orders for the sledgehammer, the masks, the grappling hook, the machete - just about everything that was found in the back of Jenkins’ van. Hines also showed the jury multiple pictures from Stepp’s mobile phone, including a blurry picture of some of the GTTF officers standing outside Stevenson’s home during the raid.

That day, Stepp said Jenkins called to tell him: “I got a monster”. When Stepp arrived, Jenkins walked out of the house with his Baltimore police vest stuffed with cocaine.

“He come out the door looking like Santa Claus.”

After the indictments, Stepp got nervous and threw seven watches worth about $200,000 into the lake behind his home.

Hines produced Ronald Hamilton’s watch, which Stepp confirmed was one that he threw into the water, only to be retrieved later by an FBI dive team.

“I thought I was going to get through, to be honest,” said Stepp. “I didn’t think [Jenkins] would reveal me.”

Stepp wears Jenkins' vest and holds his gun at BPD headquarters.

Hersl’s lawyer, Purpura, admitted his client had taken money, but argued that it was theft, not robbery, and the government had overcharged him.

He got current Baltimore police officers to admit on the stand there was a long-standing department practice of offering overtime as a reward for seizing a gun.

Taylor’s lawyer tried to convince the jury that “he sits before you, innocent”.

When word came that, after two days, the jury had a verdict, a tremulous man named Alex Hilton walked into the courthouse. He’d been arrested by Hersl multiple times, and was clearly disturbed by what he went through.

“If he was to get convicted, it would be some semblance of justice for me, I could have some closure, move on with my life without being afraid,” he said, his whole body trembling with emotion. “These are cops we’re talking about, for crying out loud.”

In the courtroom, Judge Blake read down the list of charges, and the jury foreman rose.

“We, the jury, find the defendant Daniel Thomas Hersl, guilty,” he read. “We, the jury, find the defendant Marcus Roosevelt Taylor, guilty.”

Jovonne Walker was arrested by Jenkins and the case was later dropped. She talks about her reaction to his arrest

As the officers’ family members silently held on to one another, Hilton clasped his hands together. “Thank you, Jesus.”

The jury convicted Hersl and Taylor on most, but not all charges. They determined the men had committed robbery, extortion and fraud, but cleared them of firearms charges. As the US marshals clicked the handcuffs closed on their wrists, Hersl’s family called out to him.

“Stay strong, Danny,” and “I love you, Danny.”

While the Taylor family walked briskly out of the courthouse without saying a word, Stephen Hersl, a retired firefighter and Daniel’s older brother, broke down in front of the television cameras.

“My brother was innocent and it was obvious,” he said, his face wet with tears. “Let’s talk about the corruption on top - everybody starts from the bottom, the little guy. My brother was a little guy.”

He vowed that someday, Daniel would write a book and out the superiors who’d allowed the GTTF to happen.

“Baltimore city, they can’t run a school system, they can’t run a police department, they can’t even run a zoo, Baltimore city!”

He abruptly turned and walked off into the night, as the sound of a lone, plaintive siren filled the night air.

Four days after the verdict, now-Corporal David McDougall sat in his black SUV outside of the federal courthouse as a cold rain misted the windows. He had eschewed his typical plaid shirt and jeans for a suit.

“This is an important day for the investigation,” he said. “It’s been a crazy journey.”

Moments earlier, Antonio “Brill” Shropshire was sentenced in front of a packed audience, including his mother, father, his two grandmothers and dozens of other friends and family who watched the proceeding with red-rimmed eyes. Several begged Judge Blake to spare Shropshire the maximum sentence so he could one day come home to his young son. McDougall sat at the prosecution’s table, alongside Wise and Hines.

Shropshire, a tall, bearded man in a maroon prison uniform, called McDougall and the government’s lawyers “liars”, and continued to deny he was ever the leader of a large-scale heroin operation. But he also promised to lead a crime-free life if he were allowed to return home.

“Heroin kills people, Mr Shropshire,” said Judge Blake. “Mr Shropshire continued to sell this poison. Does that mean he’s a monster? Of course not.”

She sentenced him to 25 years in prison. Both Shropshire and Glen Kyle Wells are appealing against their convictions.

McDougall said he thought the sentence was fair, and was pleased by the guilty verdicts at the GTTF trial. But he doesn’t get too emotional about this stuff.

“It’s just part of the job. Just going through the steps now.”

None of the eight officers has been sentenced - Judge Blake is expected to make those decisions in spring. Hendrix, Ward, Allers and Rayam are facing 20 years; Gondo, Hersl and Taylor could get up to 60 years.

Wayne Jenkins is expected to receive between 20 and 30 years in federal prison. Should he choose to make a statement, the sentencing would be the first time the public will hear directly from him. Through his lawyer, he declined to comment for this story.

It will also be the first opportunity his victims will have to address him, a day that Ronald Hamilton is eagerly awaiting.

“I’ll be the first one,” he said. “This has ruined me. This has crushed me.”

In the course of testimony, the names of an additional 11 current and former Baltimore city police officers came out, including a former partner of Jenkins’ and a high-ranking deputy commissioner. None has been charged, and a spokesman for the Baltimore Police Department says they are actively investigating the allegations raised at trial. One commander was demoted. Two lieutenants who directly supervised Jenkins remain on the force.

“It ain’t over. It’s just begun,” says Shawn Whiting, who pointed out his arrest involved additional officers. “It’s way far bigger than people think.”

Baltimore mayor Catherine Pugh fired Commissioner Kevin Davis the Friday before the GTTF trial began, citing “impatience” with the climbing homicide rate. Davis was replaced by his deputy commissioner Darryl De Sousa, who announced a slew of reforms, including random ethics tests and polygraphs for officers. According to a spokesman, new checks and balances will be implemented to make sure gun cases are tracked from “arrest to adjudication”, and an anti-corruption unit will be established to focus specifically on the misconduct of the Gun Trace Task Force officers.

Critics have questioned how an investigative unit housed within the BPD will be any different than the current Internal Affairs division, which failed to root out the GTTF officers.

“We still believe we have the capability to investigate on our own - we have to, that’s the bottom line,” says TJ Smith, chief of media relations.

After years of fighting for the right to view officers’ Internal Affairs files, Deborah Katz Levi, in charge of the public defender's special litigation projects, says that a month after the end of the trial she’s suddenly been granted “unparalleled access” to 21 officers’ files, including some members of the GTTF.

Levi says they're now working with the State's Attorney's Office to expand the number of convictions "that need to be undone". The office says their initial assessment concluded that 284 cases - active or closed - have been affected by the seven originally indicted GTTF officers. Mosby's office will only proceed on three active cases. She has also told the media that after factoring in the expanded timeline and additional officers whose names arose at trial, the number of cases involved could rise to “thousands”.

Mosby fired an assistant state’s attorney from her staff in February, but has never said whether this person leaked information to Jenkins.

“The [US Attorney's office] has shared components of its GTTF investigation with our office and we are not at liberty to comment,” Mosby’s spokeswoman wrote.

The ripple effects of the case are constant and ongoing. Andre Crowder and other victims of the GTTF moved away from the city of Baltimore for fear of retaliation. Sticky, the alleged murderer of Davon Robinson, will go on trial this spring. He has pleaded not guilty.

Among Baltimore citizens and police officers alike, there is sharp disagreement on how Sean Suiter died. Earlier this year, the FBI declined to take the case.

A state senator proposed the creation of a special commission with subpoena power to perform a detailed two-year investigation into the GTTF, and answer the lingering questions surrounding the BPD. However, Mayor Pugh says the police department is already under federal oversight, and that her changes to the upper ranks will be sufficient to address the GTTF’s impact.

“I believe in the work that is currently already under way,” she says.

Back in Harford County, new dealers have stepped into the vacuum left by Shropshire and Anderson. There have been 103 overdoses in 2018, so far, putting the county on track for another record breaking year.

McDougall continues to investigate overdoses. He arrives on the scene of parents’ worst nightmares, he removes bodies from childhood bedrooms. He admits there’s a feeling he’s chasing his own tail, sometimes.

“Somebody’s got to do the job,” he says. ”That’s me.”