Had things turned out differently, the quiet man shivering beside me in London’s autumn chill could have been the King of Burma, a head of state for more than 50 million people.

A neat black moustache is the only thing about U Soe Win that might hint at royal lineage. I’ve spent years in Myanmar, the country once known as Burma, and have met only a handful of men capable of growing one, though portraits of Soe Win’s ancestors suggest that a noble set of whiskers was a key part of the king’s job spec.

Moustache aside, my 70-year-old friend has spent his whole life blending into the background and keeping a low profile.

Burma’s ruling generals didn’t want royal competition, so for three decades he worked quietly in the diplomatic service - one official among many, representing a country that was for much of that time an international pariah.

As we stand on the street waiting for John Clarke, curator of South-East Asia at the Victoria & Albert Museum, Soe Win shifts his weight from one blue-looking sandaled foot to another, taking care to keep his traditional longyi out of icy puddles.

“I can see why you British came to Burma,” he says. He chuckles. We agree that shoes might be sensible for the rest of his visit.

Over the three years I’ve known him, I’ve grown deeply fond of this unassuming man, 40 years my senior, whose eyes perpetually twinkle with humour.

Our goal at the museum is to see valuable artefacts that once belonged to Soe Win’s family - and, some might argue, rightfully still do. But we are also on a treasure hunt for a ruby, a very big ruby.

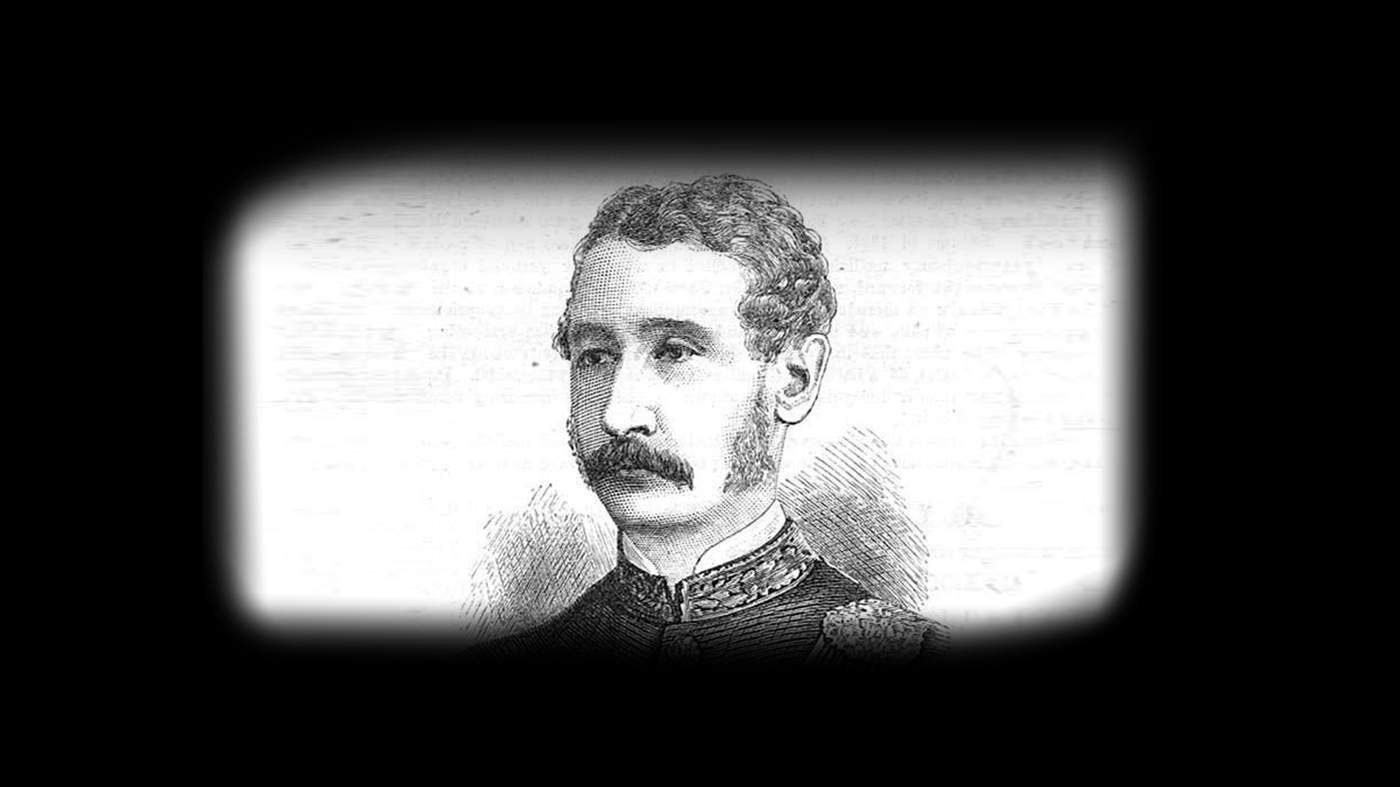

King Thibaw

As Clarke whisks us through galleries and down corridors, he explains how for many years the V&A was home to the most extensive collection of Burmese art in the world - the Mandalay Regalia.

Some 167 gold and gem-studded items ranging from weaponry, to cutlery, to footwear, were seized from the last king - Soe Win’s great-grandfather - when he was sent into exile by the British in 1885.

In 1964, however, they were given back to Burma’s strongman ruler General Ne Win as a gesture of goodwill.

All except one piece, which the general returned to the museum as a gift - a gold and bejewelled hintha, a chubby, mystical goose-like creature with a sardonic expression. Could this, I wonder, have been a typically Burmese ironic jab at the former colonial master?

John Clarke shows Soe Win the V&A's Burmese artefacts

Eventually, Soe Win asks the question. What happened to his great-grandfather’s jewel - the Nga Mauk ruby? A precious stone the size of a duck egg or betel nut, famously said to be “worth a kingdom” in its own right. A stone that glowed red, according to those who saw it, cured various ailments and bestowed great fortune on the owner? Had it been noticed at some point?

“The Nga Mauk is not, nor ever has been, here I’m afraid,” Clarke replies. “I think the most likely thing is it may be somewhere like the Royal Collection. I think that’s possible, because I seem to remember a reference to it being given to Queen Victoria.”

When I first met Soe Win back in 2014, in his little house by Yangon’s circular commuter railway, he told me he’d never go to London. Already long retired, he’d spent his diplomatic career worrying that he might be posted to live among the people who had exiled his great-grandfather, ruined his family and occupied his country.

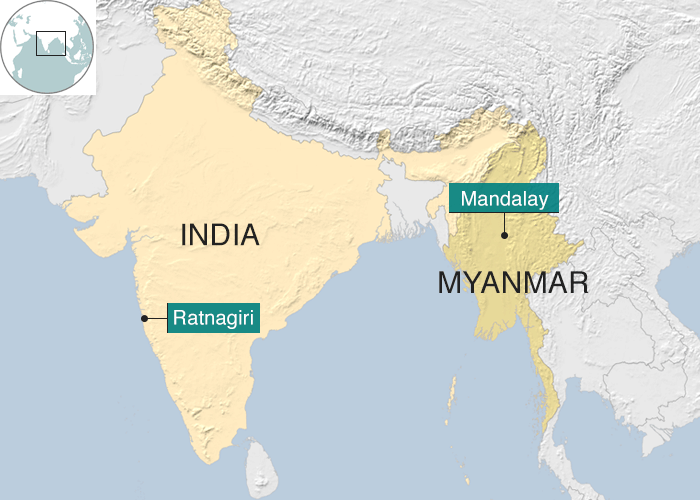

It’s a chapter of colonial history that few in the UK know the first thing about. In November 1885 10,000 soldiers were sent to topple Burma’s king from his throne in Mandalay Palace. The invasion was the culmination of six decades of tension and sporadic conflict between the British and the Burmese, caused among other things by the refusal of British dignitaries to remove their shoes in the presence of the Burmese monarch.

King Thibaw and Queen Supayalat

But the main consideration was commerce. In the eyes of the British government and the merchants of the great imperial cities, King Thibaw was an unpredictable obstacle to British trade with China. There was also a risk that he would open a back door to the French, who were expanding their own imperial territories west from Indo-China - worryingly close to India, the jewel in Britain’s crown. Thibaw had to go.

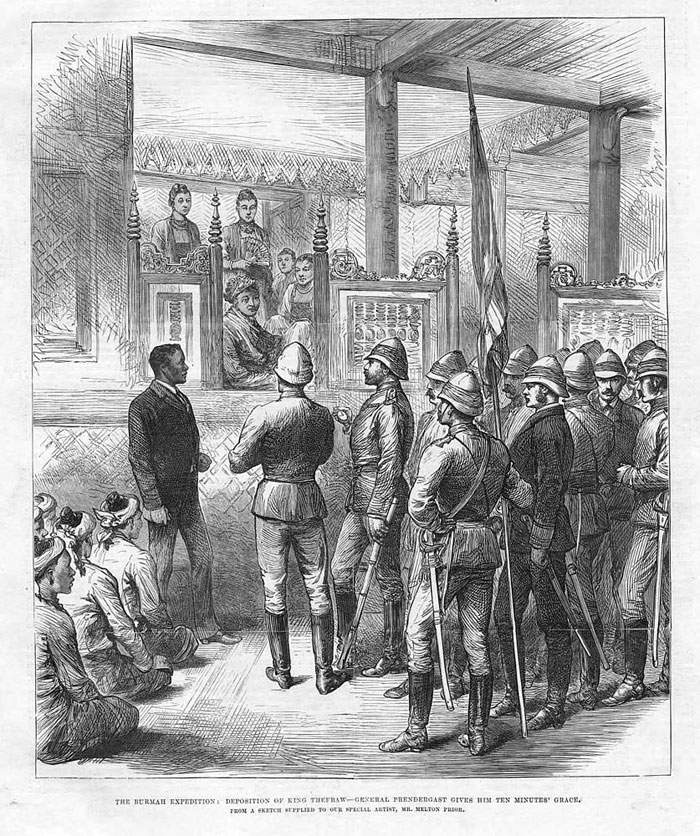

The Third Anglo-Burmese War, as it’s known, was a hopelessly one-sided affair.

In just two weeks, Thibaw was surrounded in his palace, and surrendered to Queen Victoria’s generals. On 29 November 1885, Thibaw, his heavily pregnant queen, Supayalat, and his two daughters were loaded on to bullock carts and escorted under armed guard to a ship that would take them thousands of miles to a small fishing town on the farthest shores of India.

For the king it would be a permanent exile – he died 30 years later, and his body remains buried in a crumbling tomb in a run-down corner of Ratnagiri.

All of which explains why Soe Win had dreaded being posted to London. But now he’s here of his own free will, on the trail of his great-grandfather’s most precious possession.

After the V&A, our search for clues takes us to the warren of basements beneath the British Museum, and to the British Library, which holds many of the administrative records relating to the annexation and British rule of Burma.

Among them is a curious object, about the size of a large take-away menu.

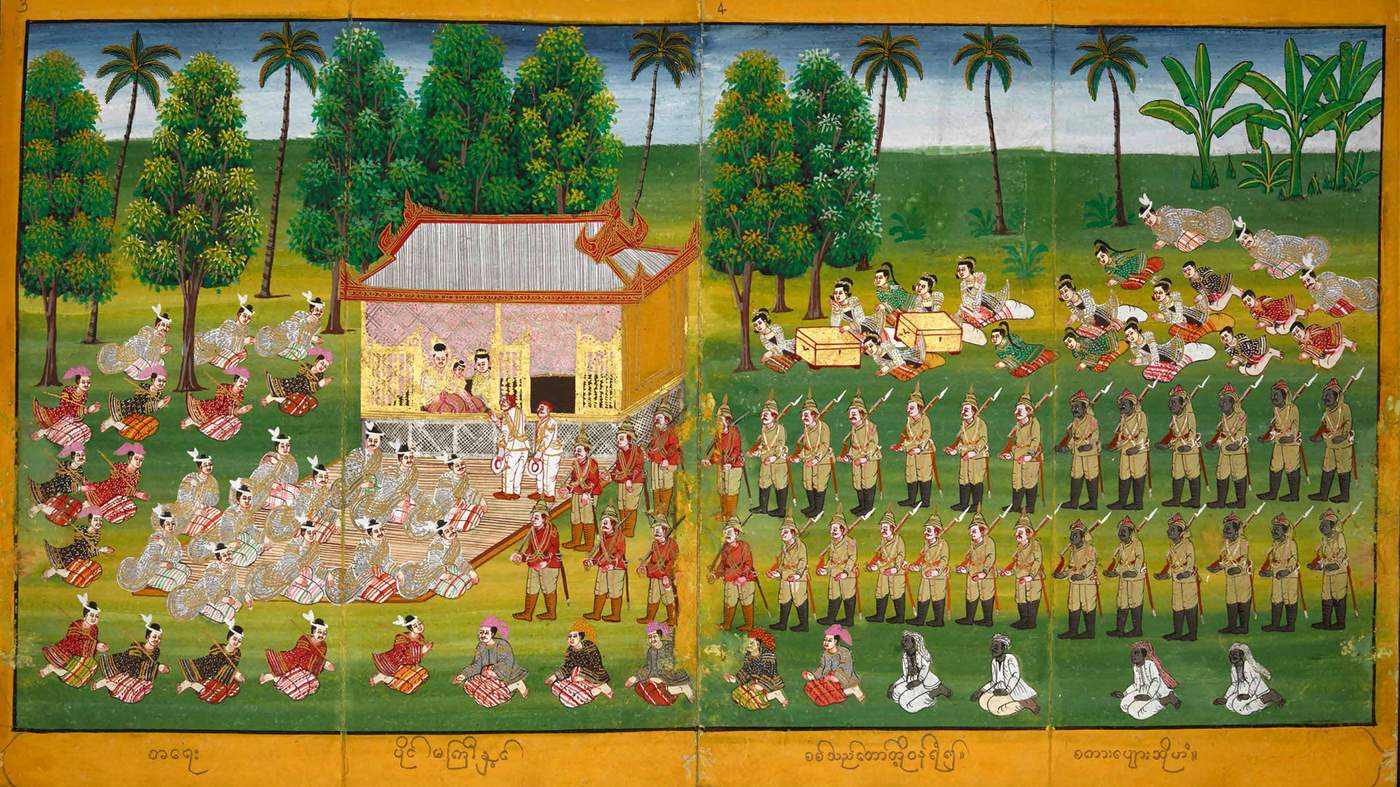

This parabaik, a folded illustrated manuscript made from mulberry-bark paper, is thought to have been painted by a Burmese artist shortly after the annexation, and tells the story of Thibaw’s downfall.

I unfold it for Soe Win in the quiet of the reading room, and his eye is drawn to one figure – a man talking to the king, resplendent in white khakis, holding his pith helmet in one hand.

“Colonel Sladen,” he whispers.

He retells a story I’ve heard many times from Burmese friends. Col Edward Sladen, a decorated veteran of Indian and Burmese campaigns, was the chief political officer of the invasion force. He was a familiar face to the king, spoke Burmese, and was entrusted with persuading him to surrender with the minimum of fuss.

Sladen would oversee the king’s hurried packing of his most valuable possessions – including the Nga Mauk ruby - in preparation for exile.

What happens next is as infamous in Burma as in India is the tale of Britain’s acquisition of the Koh-i-Noor diamond - the dazzling 106-carat gem now set in the front of the Queen Mother’s Crown.

The king’s youngest daughter wrote years later:

Sladen asked my parents to let him have a look at [the ruby] and they gave it to him. My parents said that, after looking at it for a while, Sladen put it into his pocket, pretending to be absent-minded, and did not return it.”

This is the story most often told in Burma, and many see Sladen’s knighthood just a few months later - for “special service in Burma” - as proof that he must have taken the ruby, donated it to Queen Victoria, and been gonged in return.

There are variations on the story, however. One says Sladen put the ruby in his pocket, and then - conscious that he was being watched - gave it back a few moments later.

King Thibaw himself said he had given the ruby to Sladen for safekeeping. From his Indian exile in June 1886 he sent a desperate letter to the British Viceroy pleading for the ruby’s return.

“The list of property forwarded herewith,” writes his secretary, “was made over to Colonel Sladen to keep for him [Thibaw] as he was afraid of losing it during the journey… Colonel Sladen promised him that the property would be returned to him when he wanted it… He hopes that His Excellency the Governor General will see fit to issue an order for the property to be returned.”

He attaches a list said to have been made by the Burmese royal treasurer on 29 November 1885, and signed off by a British political officer. It includes:

“1 ruby ring known by the name of ‘Nagamauk’”.

Thibaw never stopped trying to get his property back. In late 1911, he made one final desperate bid, writing directly to the newly-crowned George V. Once again he described how “my precious ruby ring (Ngamauk) was taken” and again named Sladen as the culprit.

By this stage, however, the British authorities were deaf to the king’s pleas, and the man he accused wasn’t about to own up, having been dead for 21 years. The king himself, ever more reclusive as his three-decade exile wore on, would pass away five years later, in 1916.

After Thibaw’s death, his youngest daughter, Soe Win’s grandmother, would take up the search for the Nga Mauk ruby, even writing a letter to the League of Nations. And when she died, Soe Win’s uncle, Taw Phaya Galae, took up the baton.

It’s thanks to this man - a fascinating figure known as the Red Prince on account of his years as a committed Communist - that Soe Win and I make a trip to the Tower of London, to inspect the Crown Jewels.

After writing numerous letters to the Queen and Prince Philip, and asking friends who visited London to check whether Sladen’s descendants were suspiciously well off, Taw Phaya Galae wrote a book setting out his theories about the fate of the ruby.

“However hard the British Imperialists tried to erase the trail of the Nga-Mauk ruby, there is compelling evidence of its existence,” he writes in The Nga Mauk Ruby in London. His theory is that the Nga Mauk may be hiding in plain sight – embedded in the Crown Jewels of Britain.

An internet search for “Nga Mauk ruby” tends to bring up multiple images of a ruby-studded Queen Elizabeth II and of the Imperial State Crown adorned with an enormous red stone - which suggests the Red Prince isn’t alone in making this supposition.

But the huge red jewel in the Imperial State Crown is the “Black Prince’s Ruby” worn by Henry V on his helmet at the Battle of Agincourt. So instead Taw Phaya Galae posits that the Nga Mauk ruby was used to decorate the Imperial Crown of India – a special crown made in 1911 for George V to wear in Delhi, when he and Queen Mary were proclaimed Emperor and Empress.

Imperial Crown of India

Although he gives no evidence for the hunch, the timing would work. An enormous spare ruby knocking around since the 1880s in the Royal Collection could theoretically have been donated for a new crown.

There is an obvious flaw in this theory: there is no ruby the size of the Nga Mauk in the Imperial Crown of India. The man who translated Taw Phaya Galae’s book into English has an answer, though. It was chopped into four, he suggests, and the parts became the centrepiece of each of the crown’s four sides.

We do know that the rubies in the crown are “of Burmese origin”, because this is stated in an official two-volume history of the Crown Jewels published in 1998. But that in itself proves little, as most of the world’s rubies come from Burma.

All the Royal Collection Trust will say is that “There is no archival documentation to indicate the origin of the rubies in the Imperial Crown of India.” They decline a request for an interview.

As Soe Win and I stand outside the battlements of the Tower of London, squat and brooding on the banks of the Thames, we cannot help wondering whether the Royal Collection is hiding something.

“I really believe it might be in here,” Soe Win confides and marches off through the portcullis gates. I have to run to catch him up.

I haven’t been to see the Crown Jewels since I was a child, and I now experience a curious mix of feelings, walking through this display of the power, pomp and prestige of the British monarchy, alongside a man who could have been a monarch himself.

Stepping on to the conveyor belt, we act like two excitable school-children, although with a combined age of 100. The regalia drift past in a sparkling blur of red, gold and silver. But we’re only interested in one piece.

When we reach the Imperial Crown of India, we linger as long as we can without causing a pile-up, and then rush round for a second go. Four rubies, each about 1.5cm in diameter twinkle out through the glass – could this be it? I stand staring so long that I lose track of Soe Win.

Soe Win's reaction to the crown jewels

I find him outside in the courtyard looking concerned. “I don’t want to go in there again,” he says. “It was like a horror movie. It was so dark, I had a bad feeling.” He clutches his chest.

He’s convinced that what he’s seen was not the Nga Mauk. He would surely have felt its presence, he says. “I want to see what they’re not showing, that’s what I came here for!” The chuckle, absent for a moment, returns.

To my mind, Soe Win’s gut instinct isn’t proof that the Nga Mauk ruby wasn’t sliced up and set in the Crown of India.

But wouldn’t it be an act of folly to take an invaluable,

enormous ruby and cut it into pieces? Who would do that?

We have to keep digging.

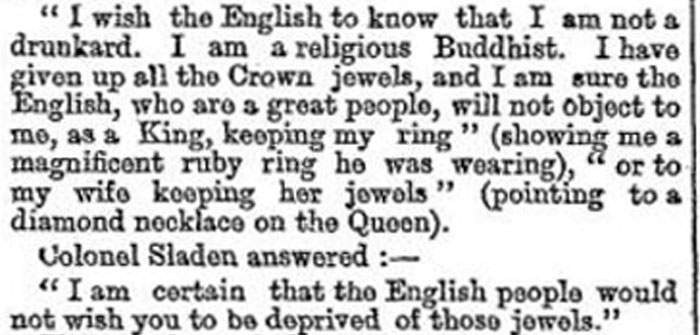

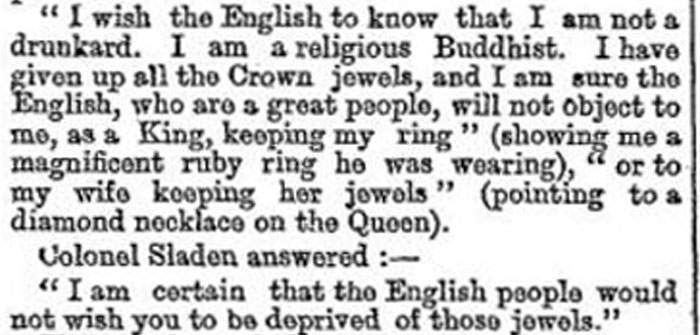

More than 130 years later, it's hard to know exactly what happened in Mandalay on 29 November 1885, the day Thibaw was exiled.

But it certainly helps that a reporter from The Times was present at one of the conversations between Sladen and the king.

The Times, 5 December 1885

I call up his report online and show it to Soe Win.

“I have given up all the Crown Jewels, and I am sure the English, who are a great people, will not object to me, as a King, keeping my ring,” Thibaw is quoted as saying.

At this point, the reporter says, Thibaw showed him “a magnificent ruby ring”.

Sladen then replies: “I am certain that the English people would not wish you to be deprived of those jewels.”

At this, Soe Win arches an eyebrow.

This has to be the ring that Thibaw wrote to the Viceroy of India about in June the following year - the one listed as “1 ruby ring known by the name of ‘Nagamauk’”.

Thibaw’s letter kicked off a wonderfully British bureaucratic paper trail, most of which is carefully preserved in the “Political and Secret” collection of the India Office Records, held in the British Library.

Opening the fragile and musty tomes, it's hard not to experience a thrill at trespassing on what were once sensitive state secrets.

In December 1886, the Viceroy asked his officers to investigate the disappearance of the ruby. All the key players in Mandalay the previous November are contacted - including the newly knighted Sladen, now back in London and preparing for retirement.

Among his personal papers, also held in the British Library, are three drafts of a letter he wrote in reply to the Viceroy’s inquiries, written over several days. It seems to me from the rephrasing and deletions that Sir Edward is having difficulty in deciding how to respond, and the final draft is a cautiously worded exercise in plausible deniability.

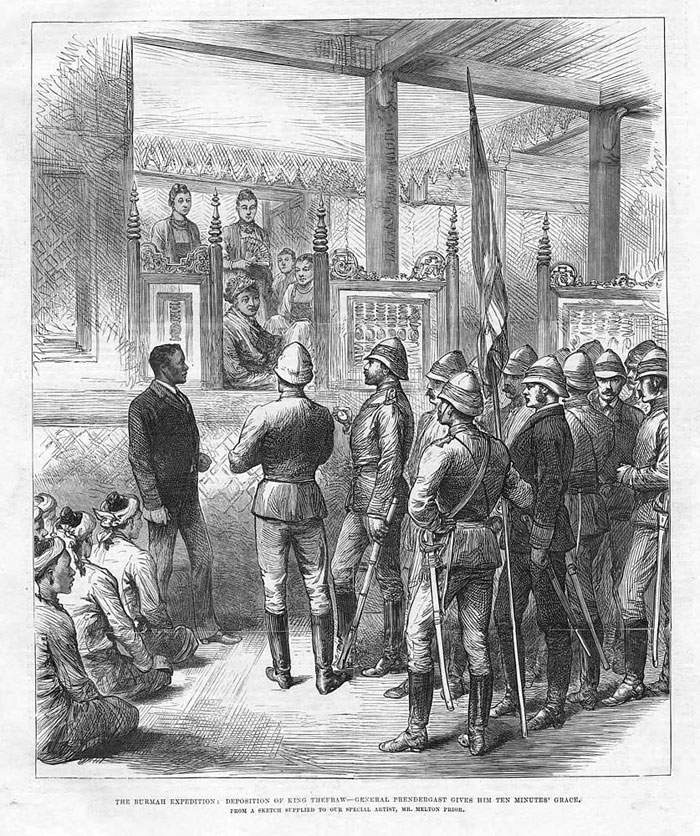

King Thibaw is given 10 minutes' grace

Due to the chaos of the day, Sladen writes, the king made “no attempt at handing over particular items or a given quantity of anything”. He denies having seen the list Thibaw attached to the letter, insists that he handed over everything in his possession, and suggests that any number of people could have made off with something so small and valuable as a ruby ring.

In a telling paragraph deleted from the final version of the letter, he says:

I looked upon the prize I had secured for the government in the person of King Thibaw, as a jewel of greater price and importance than all the other baubles in the world.”

Focus on Thibaw, he seems to be saying, and don’t fuss about baubles.

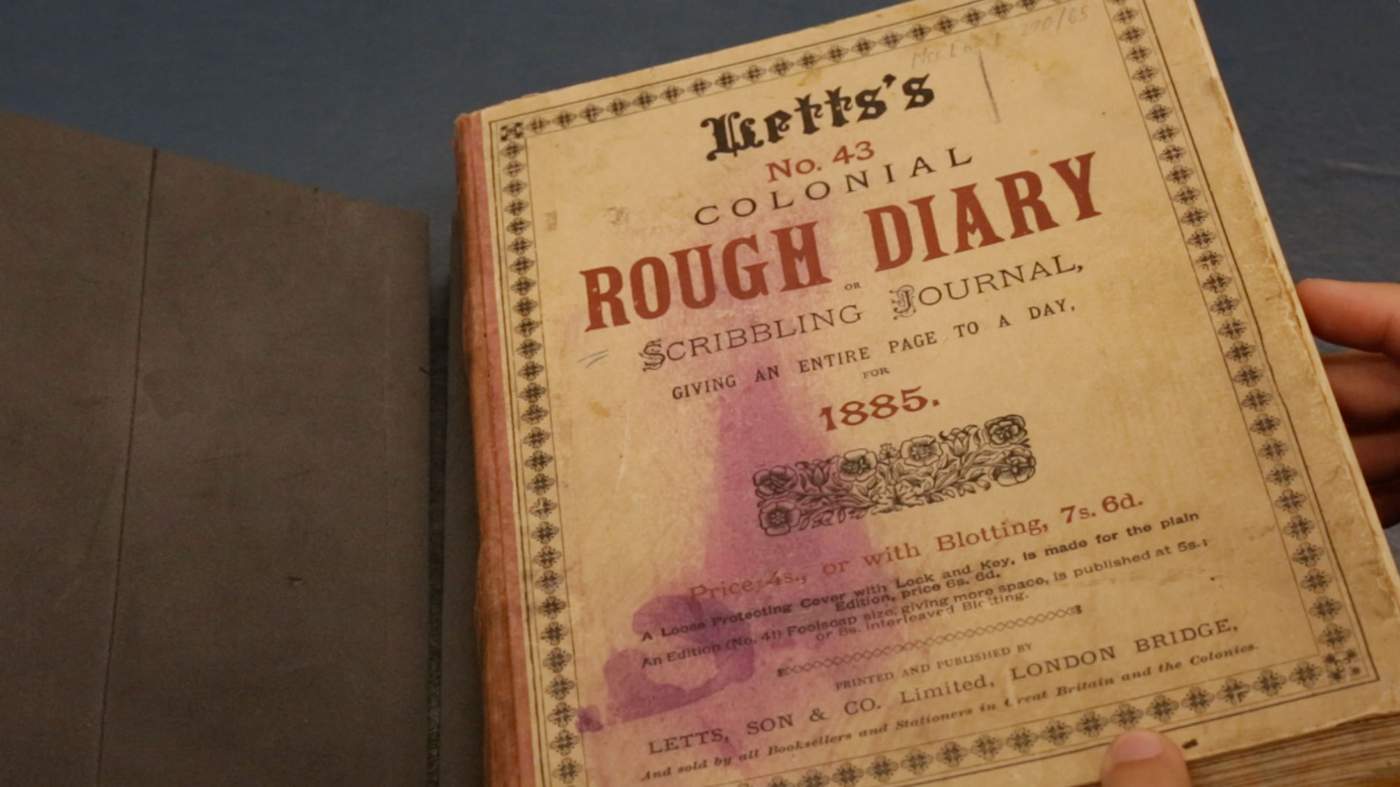

Even more curious is a large beige book – a Lett’s No.43 Colonial Rough Diary & Scribbling Journal, from 1885, the year of the annexation. It’s battered and stained with what looks like red wine. It’s a book that, like its author, has been places and seen things.

Turning carefully through the pages, I feel like I’m invading the privacy of this bewhiskered Victorian officer, who for so long has been the pantomime villain of Burmese retellings of the Nga Mauk story. Inside is a breathtaking account of the preparations for the invasion, mixed with comments on the weather, his health, and the odd spot of lawn tennis.

Having read Sladen’s letters, I’ve grown accustomed to his spidery handwriting, but interpreting the fine pencil script takes countless hours of staring and guesswork.

Finally, I reach Sunday 29 November, the day after Sladen has accepted Thibaw’s surrender, and the king’s last day in his kingdom.

My friend, Sudha Shah, who spent seven years researching Thibaw’s story for her book, The King in Exile, has warned me what to expect.

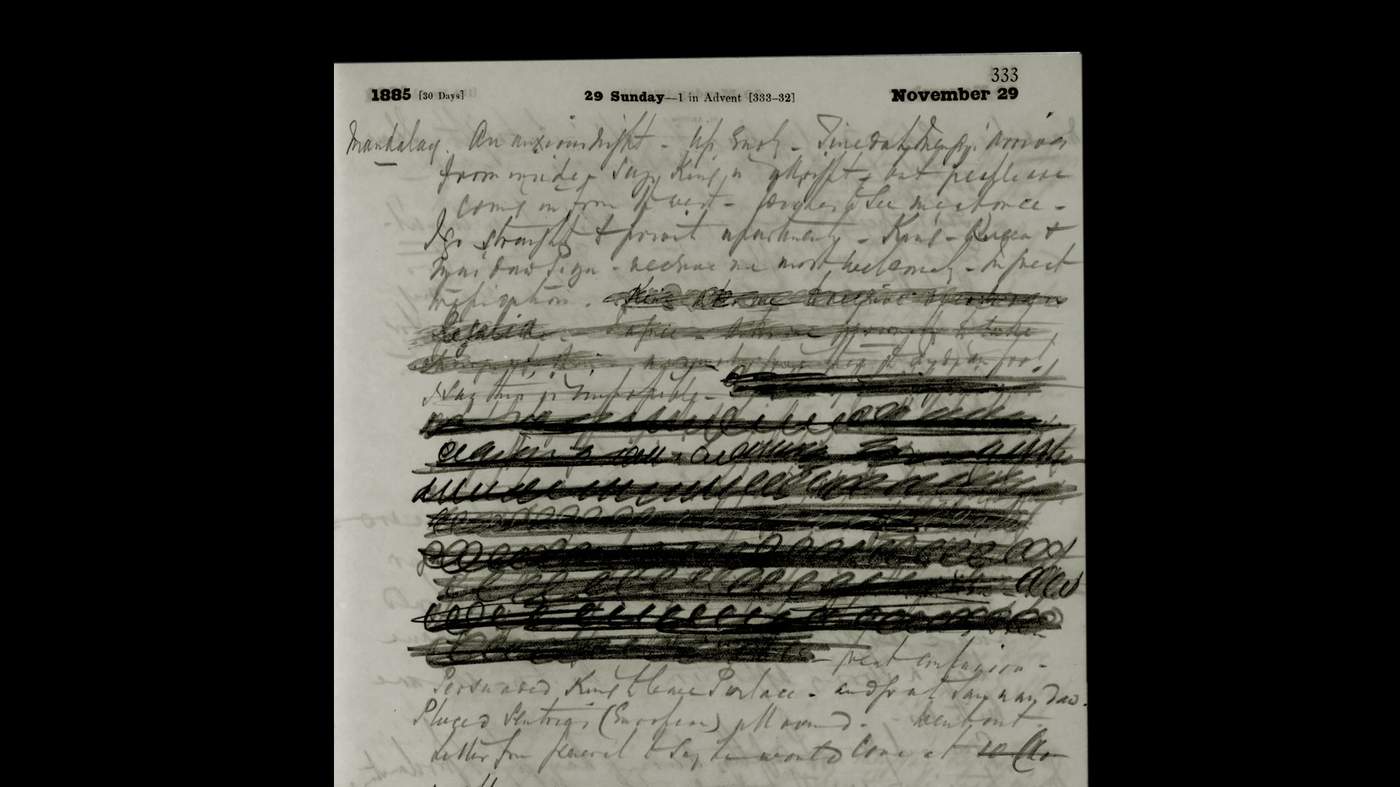

And there it is - the middle third of the page, a full 12 lines, has been industriously blacked out. The first three lines are covered with dark ink, and then perhaps running out, the vandal has switched to pencil. In the whole diary, this is the only page that has been redacted. It’s deeply suspicious.

John O’Brien, archivist at the British Library, offers to peer at the scribbling out, using a technique called multi-spectral imaging - examining the text under light of different wavelengths in the hope of revealing the original words.

More than 130 years later, it's hard to know exactly what happened in Mandalay on 29 November 1885, the day Thibaw was exiled.

But it certainly helps that a reporter from The Times was present at one of the conversations between Sladen and the king.

The Times, 5 December 1885

I call up his report online and show it to Soe Win.

“I have given up all the Crown Jewels, and I am sure the English, who are a great people, will not object to me, as a King, keeping my ring,” Thibaw is quoted as saying.

At this point, the reporter says, Thibaw showed him “a magnificent ruby ring”.

Sladen then replies: “I am certain that the English people would not wish you to be deprived of those jewels.”

At this, Soe Win arches an eyebrow.

This has to be the ring that Thibaw wrote to the Viceroy of India about in June the following year - the one listed as “1 ruby ring known by the name of ‘Nagamauk’”.

Thibaw’s letter kicked off a wonderfully British bureaucratic paper trail, most of which is carefully preserved in the “Political and Secret” collection of the India Office Records, held in the British Library.

Opening the fragile and musty tomes, it's hard not to experience a thrill at trespassing on what were once sensitive state secrets.

In December 1886, the Viceroy asked his officers to investigate the disappearance of the ruby. All the key players in Mandalay the previous November are contacted - including the newly knighted Sladen, now back in London and preparing for retirement.

Among his personal papers, also held in the British Library, are three drafts of a letter he wrote in reply to the Viceroy’s inquiries, written over several days. It seems to me from the rephrasing and deletions that Sir Edward is having difficulty in deciding how to respond, and the final draft is a cautiously worded exercise in plausible deniability.

King Thibaw is given 10 minutes' grace

Due to the chaos of the day, Sladen writes, the king made “no attempt at handing over particular items or a given quantity of anything”. He denies having seen the list Thibaw attached to the letter, insists that he handed over everything in his possession, and suggests that any number of people could have made off with something so small and valuable as a ruby ring.

In a telling paragraph deleted from the final version of the letter, he says:

I looked upon the prize I had secured for the government in the person of King Thibaw, as a jewel of greater price and importance than all the other baubles in the world.”

Focus on Thibaw, he seems to be saying, and don’t fuss about baubles.

Even more curious is a large beige book – a Lett’s No.43 Colonial Rough Diary & Scribbling Journal, from 1885, the year of the annexation. It’s battered and stained with what looks like red wine. It’s a book that, like its author, has been places and seen things.

Turning carefully through the pages, I feel like I’m invading the privacy of this bewhiskered Victorian officer, who for so long has been the pantomime villain of Burmese retellings of the Nga Mauk story. Inside is a breathtaking account of the preparations for the invasion, mixed with comments on the weather, his health, and the odd spot of lawn tennis.

Having read Sladen’s letters, I’ve grown accustomed to his spidery handwriting, but interpreting the fine pencil script takes countless hours of staring and guesswork.

Finally, I reach Sunday 29 November, the day after Sladen has accepted Thibaw’s surrender, and the king’s last day in his kingdom.

My friend, Sudha Shah, who spent seven years researching Thibaw’s story for her book, The King in Exile, has warned me what to expect.

And there it is - the middle third of the page, a full 12 lines, has been industriously blacked out. The first three lines are covered with dark ink, and then perhaps running out, the vandal has switched to pencil. In the whole diary, this is the only page that has been redacted. It’s deeply suspicious.

John O’Brien, archivist at the British Library, offers to peer at the scribbling out, using a technique called multi-spectral imaging - examining the text under light of different wavelengths in the hope of revealing the original words.

When I see what the conservation team sends back a few days later, I cannot wait to share it with Soe Win.

Where the original pencil has been scribbled out with pencil, nothing can be made out. But where the pencil has been covered in ink Sladen’s handwriting can now be seen, and a few intriguing words jump out for the first time in more than a century.

King asks me to receive over… Regalia – I agree – asks me personally to take K…”

The next three words are illegible. I want to read “King’s Nga Mauk…” but honestly, it could be anything.

“Is this proof enough for you that Sladen took the Nga Mauk?” I ask Soe Win.

“That's why he blacked it out, it's very simple.” he responds.

Soe Win looks at the diary

But I’m left with a feeling of having snatched defeat from the jaws of victory. In my mind’s eye, I can see an ageing Sir Edward worriedly chewing his pen in his London club, struggling to compose a response to the Viceroy.

I can imagine him looking back at his diary from the year before and hurriedly scribbling out an admission that he knows will haunt him. But it seems we’ll never know what the hidden text says. We’ll never even know for sure whether it was Sir Edward himself who did the scribbling out

What if Sladen did take the ruby, though? What might he have done with it?

It’s a question I put to Sladen’s great-grandson, the Earl of Portsmouth, at his house in Farleigh Wallop deep in the Hampshire countryside. We’re standing by a wall-mounted display box, containing three of Sir Edward’s medals awarded by Queen Victoria.

“Clearly he must have been an able soldier and administrator, hence his knighthood,” says Lord Portsmouth, leaning closer to examine the medals.

The earl continues:

There was some vague family rumour about Sir Edward ‘stealing Thibaw’s throne’ but the first I’d heard of the ruby was from you.”

“Besides, if he’d stolen it and kept it then where’s the money? The Sladens, my mother’s family, were a hard-up bunch. Sir Edward’s son, my grandfather, turned to elephant hunting in Kenya to make a living.”

So perhaps, if Sladen did take the ruby, we should conclude he gave it to the Queen, as might any loyal Victorian officer. But why would he have needed to hide this from the Viceroy and to scrub the record from his diary? Like everything else about this story, it’s puzzling.

Soe Win and I have not quite exhausted all our leads. Still nagging is what John Clarke at the V&A told us about a large ruby being donated to Queen Victoria. If we couldn’t prove who took the Nga Mauk, could we at least prove who received it?

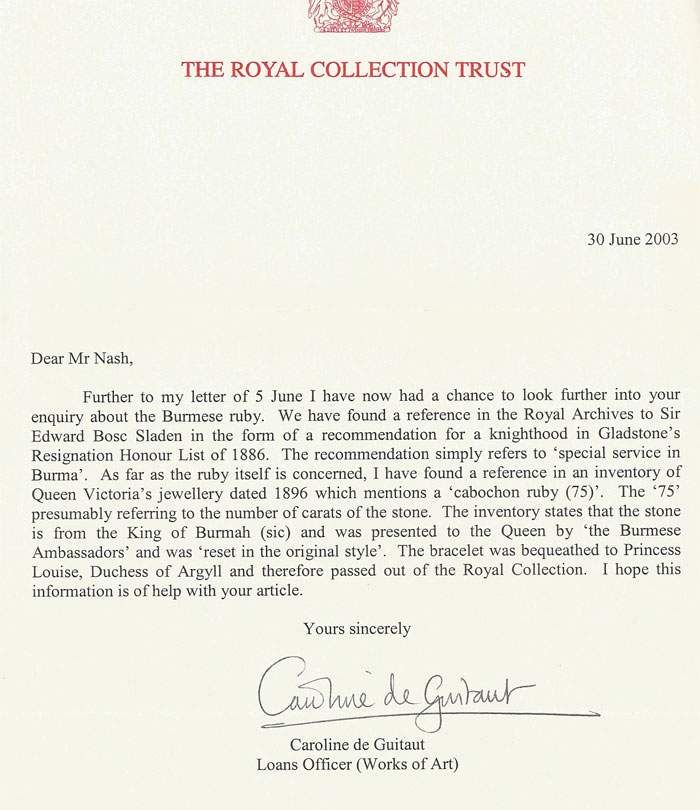

After doing some digging of his own, Clarke sends me an obscure article written in 2003 by a man called Michael Nash. Like me, Nash had caught Nga Mauk fever, and had written to the Royal Collection with the same questions as I had.

He had more luck however.

I find out that Nash is now a professor at the University of East Anglia and call him instantly to hear more about his search, and his theory about the fate of the ruby.

When everyone says nobody knows, it's not true. Somebody knows, we just don't know who that is!”

The high point of his hunt had been an intriguing letter from Caroline de Guitaut at the Royal Collection, revealing that she had found a reference in an 1896 inventory of Queen Victoria’s jewellery to a “cabochon ruby (75)”.

This may refer to the number of carats of the stone, de Guitaut says. Seventy-five carats is slightly smaller than the Nga Mauk, which was once more than 80 carats, but it could have been recut.

“The inventory states that the stone is from the King of Burmah (sic) and was presented to the Queen ‘by the Burmese Ambassadors’ and was reset in the original style,” de Guitaut goes on.

So where is it now?

“The bracelet was bequeathed to Princess Louise, Duchess of Argyll, and therefore passed out of the Royal Collection.”

Nash wrote to the current Duke of Argyll, who told him no such jewel remained in the family’s possession. Princess Louise, Queen Victoria’s artistic fourth daughter, appears to have given or bequeathed the ruby to someone, but whom?

“As a member of the immediate royal family, Princess Louise’s Will remains sealed,” says Nash, the author of a book on royal wills published earlier this year.

“Never say never, but it will be very difficult indeed to discover who Louise left the ruby to.”

Did Princess Louise’s bracelet contain the Nga Mauk ruby?

Princess Louise

It’s certainly possible.

It would be interesting to learn more about the circumstances in which “the Burmese Ambassadors” made their gift. If it took place in 1872, when Thibaw’s father, King Mindon, sent an embassy to London, the ruby cannot be the Nga Mauk. But then, maybe the reference to the ambassadors is just a smokescreen.

In Burma, the British colonialists are suspected of all kinds of subterfuge.

The loss of the Nga Mauk continues to stir huge emotion, mixed with anger at the British annexation. The famous Burmese historian, U Than Tun, wrote that “the only reasonable conclusion to be made was that a massive collective fraud was perpetrated by the British government…”

Another historian concludes: “Sladen and his cohorts carried out trickery and theft on a massive scale; destroying and distorting all existing evidence as much as possible and covering their tracks.”

Daw Ni Ni Myint, a historian twice-married to Burma’s General Ne Win, strikes a more wistful note.

The ruby that is worth a kingdom must be somewhere in the world. How I long to see if for myself and I am convinced that every Myanmar citizen will share my fervent wish.”

Soe Win certainly does. Though when I ask him why he wants to find the priceless jewel that was once the personal property of his great-grandfather, his answer is not the one many might expect.

“You have so much to show from your history, we have nothing,” he says.

It was something he’d been pondering since we followed the crowds through Buckingham Palace, a royal dwelling stuffed with carefully curated artefacts from all over the world. Later, after being guided through racks upon racks of Burmese artefacts in the British Museum and the V&A, he told me Myanmar would be eager even to have replicas of these things.

For him, the chief value of the Nga Mauk would be educational, motivational - a talisman that could help unite and rebuild the nation.

“The Nga Mauk reminds us of what we had, and what we could do. It reminds us that once we were a proud, independent nation with a rich history. We have nothing to show from that now to teach the next generations in Myanmar,” he says.

I’ve heard this many times from the last king’s descendants. They don’t want to get rich or take back power, they just want people in Myanmar to be able to remember where they came from, in the hope they may then know where they’re going.

This is more important now than ever, as Myanmar's ethnic and religious conflicts - this time in Rakhine - dominate the headlines.

To mark Soe Win’s final day in London, we order stout, his favourite beer, in a traditional English pub. For the man who swore he’d never come to London, he’s taken to it well.

“We have shared history, you and I. Not all good! But you and I are friends, and we must work together,” he tells me.

Soe Win might be 70 but he has no plans to rest – while the Nga Mauk may stay hidden for now, he’s determined to bring his great-grandfather’s remains back from India, to restore Mandalay Palace to its former glory, and to support museums in his country - perhaps with the help of the old enemy.

“We can forgive,” he says, taking a thoughtful sip, “but we mustn’t forget.”