Modern Moscow may be described as a Disneyland for adults.

Imagine a European capital, proud Muscovites like to say, think of the architectural monuments, museums, restaurants and bars in the city centre, and now multiply that by ten: now you’re close to imagining what Moscow is like.

The Arseny Morozov building on Vozdvizhenka Street and, behind it, the MosSelProm building in the classic Consructivist style

At the heart of Moscow lies the Kremlin, a fortified complex that has been continuously inhabited for over 2,000 years.

Overlooking Red Square and the Moskva River, the Kremlin is home to five palaces, four cathedrals and the ornate building that used to be home to many of Russia’s tsars.

Step back from Moscow’s crowded main streets and you can still find some well-preserved old quarters, like the small alleys, ancient churches and houses built in the 18th and 19th centuries between Kitai Gorod and Taganskaya metro stations.

The area around Kitai Gorod metro station

Zamoskvorechye, which translates as ‘across the Moskva River’, is a leafy area now bustling with open-air street cafes that was once settled by the Russian merchant class. The district still consists mainly of low-rise pre-revolutionary buildings and luxurious houses built at the beginning of the 20th century.

It’s also home to the Tretyakov Gallery, one of the largest collections of Russian fine art in the world.

Chernigovsky Lane in Zamoskvorechye

Beside Kropotkinskaya metro station you will find Ostozhenka and Prechistenka streets, often dubbed Moscow’s ‘golden mile’. Still a prestigious area today, it used to house the capital’s wealthy elite before the revolution in 1917.

Serviced apartments on 2nd Obydensky Lane near Kropotkinskaya metro

A stone’s throw from the metro stands the imposing Cathedral of Christ the Saviour. Built in the 19th century, the cathedral was the scene of the world premiere of Tchaikovsky’s ‘1812 Overture’ in 1882.

But in 1931 it was destroyed under the orders of Josef Stalin and for years served as an open-air swimming pool. It was rebuilt in the 1990s.

You have probably heard of the Arbat, a central Moscow street that is a prime tourist draw.

In our opinion, however, the Arbat is best avoided, since its main aim is to empty the wallets of visitors to the capital.

The alleys adjacent to the Arbat, however, are far more authentic Moscow – both beautiful and well-suited to a leisurely walk.

Bolshoi Afanasiyevsky Lane, close to the Arbat

Stroll through the Frunzenskaya neighbourhood to discover Novodevichy cemetery, where members of Russia’s cultural, political and military elite are buried. Here lie the bones of writers Anton Chekhov, Mikhail Bulgakov and Nikolai Gogol, poet Vladimir Mayakovsky, composers Dmitry Shostakovich and Sergei Prokofiev, among others.

A classic Constructivist building, once a canteen and recreation centre and now a hospital, close to Sportivnaya metro

Further on is the Luzhniki Stadium, where the first and last matches of the World Cup are to be played.

Luzhniki Stadium

Don’t confuse this stadium with the Spartak Stadium, another of the World Cup grounds, in the north of the city.

There is little to do in the neighbourhood surrounding Spartak, although a museum dedicated to the club’s history would make a fascinating detour.

Spartak Stadium

Two more things you must not miss in Moscow: a boat trip down the Moskva River and a tour of the city’s magnificent metro system, which Muscovites consider to be the most beautiful in the world.

Built of marble with cut-glass chandeliers hanging from the ceilings, the most impressive stations are Mayakovskaya or any of the stations on the inner (brown) circle line.

It’s also worth taking a trip to Ploshchad Revolutsii (Revolution Square) metro, where statues of four dogs, alongside those of peasants and workers, have shining bronze noses: superstition dictates that rubbing the dogs’ noses will bring you good luck.

Olimp Rudakov, who posed in his youth for this sculpture at Ploshchad Revolutsii station, went on to become a high-ranking naval captain.

There is no point in recommending a single eatery, as there are so many of them. But for the largest concentration of restaurants, cafes, bars and pubs, where you can dine for 20 euros or 200, remember the names of these streets: Myasnitskaya, Maroseika, Pokrovka, Bolshaya Dmitrovka and Stoleshnikov Lane.

Lunch with a view over the city can be had in one of the famous Stalin skyscrapers (known as the Seven Sisters) – for example the Radisson hotel near Kievskaya metro – or in one of the skyscrapers in Moscow City.

And don’t miss a trip to a completely new Moscow landmark, Zaryadye Park, just beside the Kremlin walls.

Zaryadye Park

Be sure to try pelmeny, the national dish of poached dumplings in broth, though you are just as likely to find the larger Georgian version, khinkali, on menus today.

Georgian cuisine, with its delicious khachapuri cheese-breads and garlicky bean dishes, is probably the most popular imported cuisine in Moscow today.

Khinkali

For souvenirs: skip the Arbat and its over-priced matrioshka dolls and fur flap-hats of questionable origin, and head instead for the gift shops at Moscow museums or the flea markets at Izmailovsky Park or the former Kristall vodka factory in Lefortovo district.

Souvenirs at the Museum of Contemporary Modern History near Pushkinskaya metro

In the summer, St Petersburg never sleeps, and this is not a figure of speech. The city’s ‘white nights’, as they are called, see the sun rise at 5 o’clock in the morning and not set until after midnight. During these summer months, the twilit streets and embankments are never empty, and bars and cafes are packed full at any time of the day or night.

Lion Bridge

St Petersburg’s opening bridges are the curse of the local and a delight to the visitor.

The bridges are raised at night to let through boats, making it impossible to cross the Neva River during those times. A new suspension bridge that doesn’t open means there’s now a way to cross to the other bank at night, but a taxi to take you there will set you back a small fortune.

That being the case, it would be advisable to stay in the city centre or on the Petrograd side of the river for easy access to the World Cup stadium.

St Petersburg Stadium

The Petrograd side is the oldest and most atmospheric district of the city.

The streets appear to be a grid, but in fact they weave a complicated labyrinth, where you can stumble across monuments in the Art Nouveau style. Walk for hours and stare at the beautiful houses or take refuge in the district’s quiet green squares.

The Petrograd district

You could also visit Sytny Market, the oldest in St Petersburg, where they sell cheese from the Caucasus, Georgian pastries, Finnish fish, fruits from the south and oriental sweets.

Not far from the market is the Alexander Park, and beyond that the Peter and Paul Fortress, the origin of St Petersburg.

It’s worth walking around the outer walls of the fortress for a stunning panoramic view of the city.

There’s even a city beach of sand made from granite.

Mikhailovsky Palace

Tram no. 3 is a cheap alternative to a tourist excursion bus. Its route takes you on a perfect sight-seeing tour of the city.

You will cross the Trinity Bridge, go past the Summer Garden, the Field of Mars and Mikhailovsky Castle, where Tsar Pavel I was killed by conspirators, go past the old-fashioned Gostiny Dvor department store and Haymarket Square, the scene of the murder in Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s classic Crime and Punishment, and end up in the Kolomna district.

Here you will find the world-famous Mariinsky Theatre (formerly the Kirov Theatre) and a mise en scene of Petersburg life: grandmothers selling strawberries from the countryside, fishermen casting their lines into the Fontanka River, teenagers jumping into the Kryukov Canal after a fight.

You will also find an array of bars, cafes and restaurants to suit every taste and purse.

The old and new buildings of the Mariinsky Theatre

Shaverma, or doner kebabs, are worth a try, but be sure to choose a clean-looking vendor so as not to lose two days of the World Cup to food-poisoning.

Shaverma

Zhukovsky, Nekrasov and Mayakovsky Streets are home to some of the city’s favourite bars.

Rubinshteina and Dumskaya Streets are often recommended to tourists, but are best avoided: Rubinshteina is aimed at visiting Muscovites with money to burn and Dumskaya can be rather unsafe.

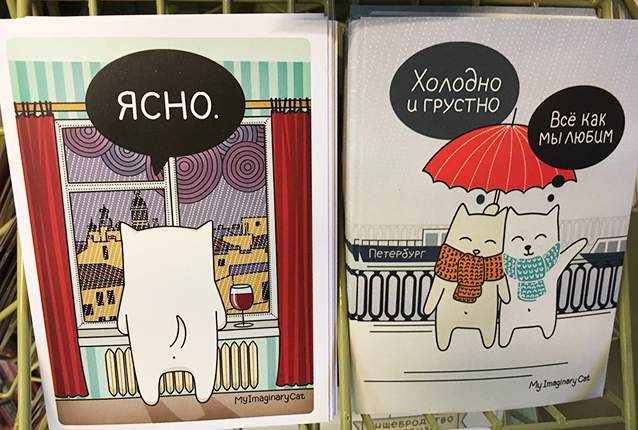

Some of the best St Petersburg souvenirs are sold at the Podpisniye Izdaniya bookstore at 57 Liteiny Prospekt. Here you can buy handmade wooden icons with portraits of Russian writers and poets, postcards and Petersburg fridge-magnets dedicated to the rainy weather and the melancholy mood of the city’s residents.

St Petersburg postcards bemoaning the weather

Finally, despite what they will tell you, Nevsky Prospekt, the city’s main thoroughfare, is best avoided.

“This Nevsky Prospekt deceives you at any time of the day or night,” the Russian author Nikolai Gogol wrote in his eponymous short story. Almost 200 years later, nothing has changed.

It’s now just a four-hour ride on the Lastochka (Swallow) or Strizh (Swift) train from the Russian capital to Nizhny, as it’s known, a fine city with river views, reasonably priced bars and some great city art.

A fine example of Nizhny street art on Plotnichny Lane

Nizhny’s street art encompasses more than 300 works scattered across the city, from murals to sculptures to graffiti.

But the first thing that catches your eye when you visit Nizhny is its location – slopes, embankments and vistas over the Volga River.

Lower Volga Embankment

On the Lower Volga embankment, take a selfie beside the metal deer created by Hungarian sculptor Gabor Miklos Szoke. Admire the ‘Chkalov Steps’, the symbol of the city, at the top of which stands a monument to Soviet pilot Valery Chkalov, who was born close to Nizhny. From here it’s a short walk to the city’s main drag, Rozhdestvenskaya Street, a great place to go bar-hopping.

The Nizhny Novgorod Kremlin is a must: stroll around its gentle slopes and admire more great views of the city.

The Kremlin is the well-spring of the city’s thriving art scene, housing both the Arsenal contemporary art centre and a museum with a rich collection of masterpieces, including one of Kazimir Malevich’s ‘Reapers’, and works by Boris Kustodiev, Nicholas Roerich and Viktor Vasnetsov.

An unofficial symbol of Nizhny is the 'blue fence', which surrounded a building site in the city centre for about ten years.

From the Fyodorovsky Embankment there are also good views of the Kanavinsky Bridge and the Alexander Nevsky Cathedral, as well as the World Cup stadium called, somewhat unimaginatively, the Nizhny Novgorod Stadium.

Nizhny Novgorod Stadium

From the Kremlin, you should walk along Bolshaya Pokrovskaya, the city’s main artery, which connects the central Minin and Pozharsky Square with Gorky Square.

Close to this square is one of the most popular shaurma (kebab) outlets in the city. Aficionados flock to this stall to eat kebabs the size of footballs.

There are a fair few kebab stalls in the area, but the one to head for is closest to Belinsky Street. There’s usually a large crowd in front of it, so it’s hard to miss.

Shaurma

Stroll along Pokrovka to see a mix of musicians, flame-throwers and street-beggars, and drop into any of the cafes for burgers, hummus or noodles.

On this street you can see the imposing neo-Russian-style State Bank building and the Drama Theatre where the legendary bass opera singer Fyodor Chaliapin made his debut.

The neo-Russian-style State Bank building

For some Soviet kitsch and nostalgia, it’s worth visiting the Kladovka art gallery.

The cable-car that crosses the Volga River to Bor

Other things you should not miss: one of the longest cable car rides in Europe – a snip at just 100 rubles one way – which takes you to the nearby town of Bor; impressive Stalinist architecture of Sotsgorod, literally a 'Socialist town', built in the 1930s around the Gorky Car Plant; Shchelokovo farm and its museum of wooden architecture; and nuclear physicist Andrei Sakharov’s house museum, where the dissident and nuclear disarmament activist lived for six years.

Our best advice for the first-time visitor to Nizhny is to stray from the beaten track and wander through quieter streets past old wooden houses to capture the real spirit of the city.

The Russian exclave of Kaliningrad – it shares no borders with ‘big Russia’, sandwiched as it is between Poland, Lithuania and the Baltic Sea – was, until 1945, the German city of Koenigsberg. However, the German character of Kaliningrad and its pre-war heritage has all but disappeared from the city.

The Brandenberg Gates, built in the 19th century

During World War II, the city was heavily damaged by a British bombing attack in 1944 and the massive Soviet siege in the spring of 1945.

What little German architecture was left after the war, when Kaliningrad became part of the Soviet Union, was often seen by the inhabitants as something alien and was therefore mercilessly destroyed.

The World Cup fan zone is located in the heart of the city, beside the huge, incomplete House of the Soviets. Construction began in the early ’70s on the site of a ruined medieval castle, but for some reason the building was never finished.

House of the Soviets

Not far from the fan zone, on the island of Kant (formerly Kneiphof) stands the city’s 14th-century cathedral.

Many consider the fact it has survived to this day, even through the air raids, to be the hand of providence.

Immanuel Kant's grave

Some Kaliningraders believe it’s the work of their genius loci, the spirit of the city’s most famous resident, philosopher Immanuel Kant, who saved the cathedral in order to keep his own grave from harm.

Amber is a traditional souvenir from Kaliningrad

After visiting the cathedral, you could walk to Rybnaya (Fish) Village, Kaliningrad’s old city, and beside it the small pre-war Honey Bridge, which also miraculously survived the bombing.

Here you will find many hotels, bars, restaurants and other entertainment venues.

Kaliningrad is a city of fishermen. Previously, its port was home to a powerful fleet, which sent ships to fish in all the oceans of the world. Kaliningrad’s most famous dish, therefore, is stroganina – carpaccio of raw, frozen fish.

Stroganina - frozen fish carpaccio

This delicacy should be eaten with toast or warm potatoes, and washed down – of course – with ice-cold vodka. But enjoying stroganina with beer isn’t entirely frowned upon, either.

Not far from the fan zone is the Museum of the Oceans of the World. Its collection includes the deep-sea diving capsule Mir-1, which, along with Mir-2, was used by Hollywood director James Cameron during the filming of his epic Titanic.

B-413

Outside the museum, a Soviet diesel-powered submarine called a B-413 is moored. This is a real combat ship, deployed during the Cold War from the late 1960s to the early 1990s, which patrolled the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea.

Kaliningrad Stadium

Yekaterinburg is a rambling city with an easy rhythm of life. The construction of the Yeltsin Centre – the former Russian president is the city’s most famous export – and a plethora of new restaurants means its centre has become a great place for a pleasant stroll.

But your walk should not start in the very centre. Begin, instead, in the Constructivist complex that spans the Chekist and Uralmash districts.

For this you should employ an experienced guide or arm yourself with a guide book from the ‘Tatlin’ publishing house.

The White Tower

Here you can see the orange-coloured Houses of Exemplary Living – a Constructivist concept devised in the 1920s, which rethought the way people should live to make it more communal.

There are many unexpected jewels, including the White Tower, a water tower and a functional monument to Constructivism, designed by Moses Reischer.

The Yeltsin Centre

From there go to the 1905 Square metro station, walk to the Yeltsin Centre, where you will need at least three hours to visit the three main exhibitions, and then walk on to the stadium, passing on your way a scattering of cafes, bars and restaurants.

Ekaterinburg Stadium

Yekaterinburg is currently experiencing a gastronomic boom, and oriental cuisine is now ubiquitous.

Near the post office at 41 Lenin Street – another great example of the Constructivist form, which has recently been scrubbed clean and brought back to life – you will find a huge range of cafes selling everything from bistro burgers to Vietnamese street food.

Two more areas for eating should be noted: the intersection of Malyshev and Khokhryakov Streets, where you can find warm waffles with bacon, Belgian beer and authentic Vietnamese Pho soup.

Pelmeny

And if you are in the Chekist district, don’t miss a plate of traditional Ural dumplings and hash.

On the souvenir front, we recommend Urals T-shirts and sweatshirts.

You can also find jewellery and ornaments with Constructivist themes – better than postcards, as they are both functional and attractive.

Many souvenirs in Yekaterinburg are made of malachite from the Ural Mountains close by

Volgograd rose from the ruins of Stalingrad after World War II and still serves as a powerful reminder of Soviet power. The city, which was given the neutral name Volgograd in 1961, remains a monument to the war, and to one of the bloodiest battles in history.

Volgograd has an imperial grandeur: in the 1950s, the city was constructed to include wide-open, steppe-like spaces and large, impressive buildings.

Heroes' Alley

For those spending a day or two in the city, you should consider a three-hour stroll from Heroes Avenue to Central Embankment, along the Volga River to the Central Park of Culture and Recreation, past the Volgograd Arena Stadium, where World Cup matches will be played, and then up to Mamayev Kurgan, the memorial complex located atop a hill overlooking the city.

The area commemorates the Battle of Stalingrad, fought between 1942 and 1943.

On it stands the giant statue of a woman holding aloft a sword, entitled ‘The Motherland Calls’. It’s the largest statue of a woman in the world.

Heroes Avenue is the city’s main promenade, along which you can find many popular cafes and restaurants.

Volgograd’s favourite food is, somewhat surpisingly, Chicken Kiev, but other popular dishes include pizza rolled into cones and pancakes with an endless variety of fillings, both savoury and sweet.

Steamed crayfish are very popular

Walking along the embankment, you can see a number of architectural gems, including the Battle of Stalingrad Panorama Museum and the pre-revolutionary structure Gerhart’s Mill.

The Battle of Stalingrad Panorama Museum and, left, Gehart's Mill

Gehart’s Mill has been preserved in its original form and today it stands as a rare monument to the pre-war red-brick architecture of Stalingrad (or Tsaritsyn, as the city was called until 1925).

But easily the most photographed place in Volgograd is Mamayev Kurgan and its 85-metre statue. This massive memorial complex is an experience that’s hard to forget.

The climb to Height 102, as this point was called during the Battle of Stalingrad, is accompanied first by military music, then the sounds of gunshots and exploding bombs, then the voice of Yuri Levitan, the most prominent Soviet radio announcer during and after World War II.

Then suddenly the sounds fall quiet, replaced by an eerie silence as you approach the Hall of Military Glory and the eternal flame.

Volgograd souvenirs, like these trinket boxes, often bear the image of the Motherland Calls statue

Finally, stand at the feet of The Motherland Calls, the tallest statue in Europe and Russia, constructed by sculptor Yevgeny Vuchetich, admire the view across the whole city and breathe in the dry steppe air: it is worth climbing the several hundred steps to experience this.

Volgograd Arena Stadium

If you want to see multinationalism and multiculturalism in Russia, look no further than Kazan. As a single region, the Republic of Tatarstan, of which Kazan is the capital, has the largest Muslim population in Russia.

The well-thought-out infrastructure and eclectic architecture of the city, some of it reminiscent of Moscow, make any walk through Kazan a kaleidoscope of impressions.

The mullti-coloured, multi-faith cathedral in Staroye Arakchino

The most unusual buildings can be found beside the presidential administration on Kasatkin Street.

There you can go to the banks of the Kazanka River and look across to the ranks of tall new buildings, two large ferris wheels and the lights of residential complexes.

One thing that might surprise you about Kazan is the lack of crowds.

Aside from bustling Bauman Street, the bars on Profsoyuznaya Street or the restaurants on Sibgat Hakim Street, the centre of Kazan is almost deserted by nine o’clock in the evening.

Kazan Arena Stadium

Some have compared Kazan to an exotic film set, full of beautiful streets and buildings, but one to which they forgot to invite any cast or crew.

Talking of exotica: you will hear trilingual announcements (in Russian, Tatar and English) when you travel on the metro in Kazan.

And if you do decide to go by metro, be sure not to miss the psychedelic mosaic at Ploshchad Tukaya station.

For souvenirs: amongst the cornucopia of Islamic souvenirs you can find beautiful ichigo, fine leather boots often covered in intricate, hand-stitched embroidery. Sometimes they have toes that curl upwards: this is connected with an old belief that people shouldn’t hurt the earth by pressing into it with their toes.

Traditional Tatar shoes

Tatarstan’s national cuisine has been actively re-interpreted by local hispters, who have come up with dishes like the black kystyburger.

Kystyby are savoury pies, usually containing potatoes or a type of porridge.

Traditional Tatar pastries

Tradition dictates that any visitor to Tatarstan should drink the local Bugulma balm and eat an echpochmak - a triangular-shaped meat pie.

Echpochmak and Bugulma

In summary, Kazan is a bustling metropolis, the sixth largest in Russia, and a city with a great history, beautiful parks and a diverse cultural life.

Samarans can’t seem to decide whether they live in a teaming metropolis or a resort on the banks of the Volga. Old wooden dwellings stand cheek-to-cheek with high-rise business centres, traditional houses jostle for space with shiny new shopping malls and the countryside surrounding the city is fast becoming urban sprawl.

Prince Grigory Zasekin, the founder of Samara

The main tourist route begins on the embankment, where you can see an eclectic array of monuments to Samara’s most revered characters.

There is a bronze statue of Prince Grigory Zasekin, the founder of Samara, astride a horse. There is a monument to the burlaks, the workers who hauled barges and other vessels upstream by hand.

The Na Dne Bar

Close to the embankment you definitely should not miss a trip to a long-standing Samara institution, a bar called Na Dne (At the Bottom) close to the Zhigulyovsky brewery.

This tiny bar serving the local beer is loved by Samarans young and old. And at 85 rubles a glass, it’s easy to see why.

To get a true feel for the city, take a stroll through the old centre, along Galaktionovskaya, Chapayevskaya and Sadovaya Streets. Here you will find decaying izby, traditional wooden huts, built by residents of years gone by.

At the crossroads of Lenin and Rabochaya Streets

Samara Arena Stadium

Tourists are usually hustled towards the pedestrian Leningradskaya Street, but frankly there is little to do here – there are just a handful of hookah joints and a hipster hang-out called Dom 77 Creative Cluster.

Head instead for Kuibyshev Street, lined with bars and restaurants often serving Georgian cuisine, and Molodogvardeiskaya Street and its collection of bars and bistros.

At the intersection of Leningrad and Kuibyshev Streets

Samarans themselves head for dinner at Dachnaya 2, Dachnaya 2G and Kommunisticheskaya 90, where several restaurants serving European cuisine are located in one block.

Here you can get delicious lagman, a Central Asian dish of noodles, vegetables and meat, and the most delicious plov, an Uzbek rice dish similar to pilaf, in the city.

Georgian cuisine

Many Samarans spend their days off on the other bank of the Volga, which is easy to get to by ferry.

In Rozhdestveno, you can hire a bike for 350 rubles, or go camping in Shiryayevo. Don’t miss the house museum of the renowned Russian realist painter Ilya Repin, or a trip to Camel Mountain, whose eastern contours really do look like a resting camel. It has unparalleled views over the Volga and is a favourite training spot for mountain climbers from all over Russia.

Climbing opportunities in Shiryayevo

On your way back, think of hiring a private boat: it will be more expensive than the public ferries, but faster and more fun.

Rodniye Prostory chocolates

Ask any Samaran what to take away with you as a souvenir and without hesitation he will reply Rodniye Prostory chocolates, made at the local chocolate factory.

Or you could buy a cluster of dried fish, but bear in mind that their odour can be pretty overpowering.

Dried fish makes a good present, if you can bear the strong smell

If you want a true feel for southern Russian mentality, then head for Rostov-on-Don. It’s a place where you can eat well and drink even better. Dried Don fish, ukha fish soup, steamed crayfish, local beer and Don wine – these are the city’s calling cards, and Rostovites will be highly indignant if you leave their city hungry or sober.

Rostov-on-Don was founded on the intersection of many trade routes, and it’s always been the home of both freedom-loving Cossacks and enterprising merchants.

Locals say you can still feel the spirit of trade, freedom and enjoyment here today. More than a hundred nationalities live in the city, and they all manage to get along with each other in peace and harmony.

A Cossack Don fridge magnet

Of course, the main attraction in Rostov is the Don River, so first of all you should head straight for the embankment: take a walk, go fishing or go out on a boat.

Don’t miss the Paramanovsky storehouses on Chekhov Street in the centre of town. These tumbledown buildings are more than 100 years old. Some of them have streams running through them, lending them the feel of ancient Roman bath houses.

The Paramonovsky storehouses

The Rostov Central Market is also a must. Right in the middle of the market, somewhat unexpectedly, stands the city’s cathedral. Despite its unusual location, it’s a stunning building and deserves special attention.

For a feel for old Rostov, stroll along Bolshaya Sadovaya Street, where 19th and early 20th-century buildings have been well preserved.

On nearby Ulyanovskaya, Shaumyan and Turgenevskaya Streets, you can see former merchants’ houses, overgrown courtyards and original paving stones. This is a great area for romantic walks. The most beautiful street in the city is widely considered to be Pushkin Street.

Bolshaya Sadovaya Street

In their spare time, Rostovites like to go to Theatre Square in October Revolution Park, where there is a huge ferris wheel, at the top of which you get panoramic views of the city.

There are fountains and the Gorky Drama Theatre, of which local residents are very proud.

Theatre Square at dusk

This 1930s Constructivist building was designed to look like a huge tractor: the architects, Vladimir Shchuko and Vladimir Gelfreikh, wanted the theatre to stand as a monument to the first of Josef Stalin’s Five-Year Plans.

A little further along Sadovaya Street you can see another Constructivist building, a musical theatre in the shape of a grand piano.

Rostov Arena Stadium on the left bank of the River Don

It’s also worth visiting the left bank of the Don. Now it is home to the World Cup stadium and the park around it and the restaurants and bars that have sprung up close by mean this, too, has become a good area in which to spend a pleasant afternoon.

If you had to sum up what it’s like to live in Sochi in three words they would be: warm, delicious and expensive. Historically, this has always been the case: a hot climate, fertile land and prices driven up by Russia’s political elite, who to this day like to spend their holidays in this pleasant seaside and mountain-side resort.

You would think that the elevated prices would mean there is service to match. But, alas, this isn’t always the case.

If you visit Sochi for just one day, you will have to make the difficult choice between three locations: Adler, Krasnaya Polyana and the city centre. It’s impossible to combine all three destinations in one day as they aren’t very close to each other and the traffic between them can be terrifying.

The 2014 Winter Olympics mascots

Our advice is to go to the Imeretinksy Valley in Adler and the Olympic Park.

Here you will find clean air, beautiful mountain views, and plenty of cafes and souvenir shops, where you can buy Olympic leopards or dolphins.

From Adler it isn’t too far to Krasnaya Polyana and its three mountain resorts: Rosa Khutor, Gorky Gorod and Gazprom Sochi. You can take a cable car high into the mountain peaks, or bungee-jump or take a zip-line deep into a valley from the bridge at the Skypark leisure centre.

Fisht Stadium

If you choose to remain in the centre of Sochi, go to the port on Nesebrskaya Street.

Here you can find an exciting mix of the old and the new: Stalinesque buildings stand beside designer fashion boutiques, against a backdrop of yachts, open-air terraces serving fresh fish and French cafes selling dainty patisseries.

Mussels with black pasta

Not far, at 9 Ordzhonikidze Street, is the oldest khinkalnaya in the city, serving khinkaly, a delicious Georgian dish of garlicky meat dumplings. This one is the most delicious and the least expensive in Sochi. You can also try shish kebabs, solyanka (a delicious sour soup) and lavash, the local bread, with goat’s cheese and vegetables, as well as finding a variety of vodkas and Georgian wines.

Don’t miss Navaginskaya Street, the popular and picturesque pedestrian zone in the centre of town.

Long-time Sochi residents like to spend time here, as well as on the Primorskaya Embankment, at the Riviera Park or at the Morye Mall (Sea Mall) entertainment and shopping centre.

After Navaginskaya you have a choice: walk to the railway station or to Platanovaya (Plane Tree) Alley. After that, take a bus or a taxi to the Dendrarium, 40 hectares of stunning parkland containing 1,500 different plants and trees.

Sochi Dendrarium

There’s plenty of cool graffiti in Sochi if you are looking for Instagram opportunities.

Try these locations for cult film and music industry illustrations: 39 Ostrovsky Street (the Soviet film The Diamond Arm), 2 Ordzhonikidze Street (the Soviet film Ostap Bender), 48 Gorky Street (Albert Einstein), 1 Nesebrskaya Street (The Beatles), Mayak beach (Jacques Cousteau).

Jacques Cousteau

Saransk, the capital city of the Republic of Mordovia, is the most provincial of the cities hosting the World Cup. Choosing it as one of the locations to hold the championship was a huge surprise, not least for residents of the city.

Women in traditional Mordovian costume

But despite its small-town feel, Saransk has something to surprise its visitors.

Signs written in four languages (Russian, English, and the two most common languages spoken in Mordovia, Erzya and Moksha) are a constant reminder that you are in a unique part of Russia.

On match days, the streets of Saransk will be hung with Mordovian symbols, and souvenir stalls will spring up all over the town. The most obvious souvenirs to go for are figures of various Mordovian pagan gods with funny names like Viryava, Paksyava and Kuygorozh.

Mordovian embroidery makes beautiful souvenirs

It is worth looking out for the carved wooden sculptures of Mordovian artists, the most famous of whom is the modern sculptor Stepan Erzya, who has been called 'the Russian Rodin'.

Wooden sculpture by Stepan Erzya

Saransk is a fairly compact city, and all major attractions and entertainment are close to the new Mordovia Arena Stadium.

Start your trip by visiting the recently-opened observation deck on the roof of Mordovia State University on Bogdan Khmelnitsky Street.

Mordovia State University

Going down from the observation deck, you can (and must!) go to the nearby Mordovian Museum of Fine Arts, where you will find a rich collection of works by Stepan Erzya, after whom the museum is named.

Moving further into the city centre, you will come to the cathedral - a modern building, but monumental and impressive in its own way.

Perhaps in the spirit of modern Russia, the cathedral is located at the intersection of Bolshevist Street and Soviet Street.

A monument to the family

It’s a little harder to find places to eat in Saransk than in the other World Cup host cities. Don’t risk your health eating shaurma or chebureki, a deep-fried pastry filled with minced meat and onions.

Instead, try ofton madyat ('bear’s paw' – actually a mix of minced beef and pork coated in breadcrumbs and shaped to look like a bear’s paw) and poza, a non-alcoholic drink made from beetroot.

Ofton Madyat, 'bear's paw', isn't really made of bear meat

Sadly for Saransk, the World Cup development has only touched the town centre.

Travel just a few miles out of the city and you will see the usual pot-holed roads, dilapidated buildings and impoverished living.

This Saransk still has outdoor toilets, drunkards loitering in doorways and rowdy youths who are not necessarily the most hospitable. But if you come to the capital of Mordovia for only one day, you are unlikely to see the grimmer reality behind the World Cup.