Valentina Timofeevna Yashina leans back in her armchair. She is talking about her husband, one of the greatest footballers of all time. Behind her, on the top shelf of a glass cabinet, there is a chocolate replica of the Ballon d’Or he won in 1963. The foil is peeling in several places now, but it is still gold.

Lev Yashin, the only goalkeeper ever awarded the prize, is an icon of the Soviet Union, the empire that fell in 1991, a year after his death at the age of 60. He is the Black Panther, the Black Spider, a legend who is nowhere more real than here in this living room, where the woman he shared his life with still speaks about him in the present tense.

Valentina is 88 years old now and she still lives in the apartment they were given by the state in 1964. Yashin looks down from the walls - frames he shares with friends and family; fellow footballing greats Franz Beckenbauer, Pele and Eusebio, his two daughters and grandchildren. In the hallway, dozens of medals hang on a red fabric strip.

Lingering cigarette smoke fades slowly from the kitchen. Valentina is comfortable, she has a mischievous smile and there is brightness in her eyes. Now she is leaning forward and urging us to listen. This is a story about a father, a goalkeeper, the country he played for which no longer exists, a time all together different to our own.

Walking beyond the padded, thick front door of Valentina’s winter-proof Moscow apartment, you step back in time into a life of a footballing legend. Everywhere you look there are posters, trophies, signed footballs - a huge number of personal treasures gathered over a remarkable career. This was Yashin’s home for 26 years.

There are so many mementos it is hard to keep track. There is the stuffed lion toy on the sofa (Lev means lion in Russian). There is a pennant from Ipswich Town - Valentina does not remember how it came to Yashin. There is the gold medal he won at the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne, a medal that was shown countless times on the long, celebratory train journey home across Russia from Vladivostok.

World Cup Willie (centre) - the mascot from the 1966 World Cup - is one of the many items adorning the flat Yashin shared with Valentina during his life

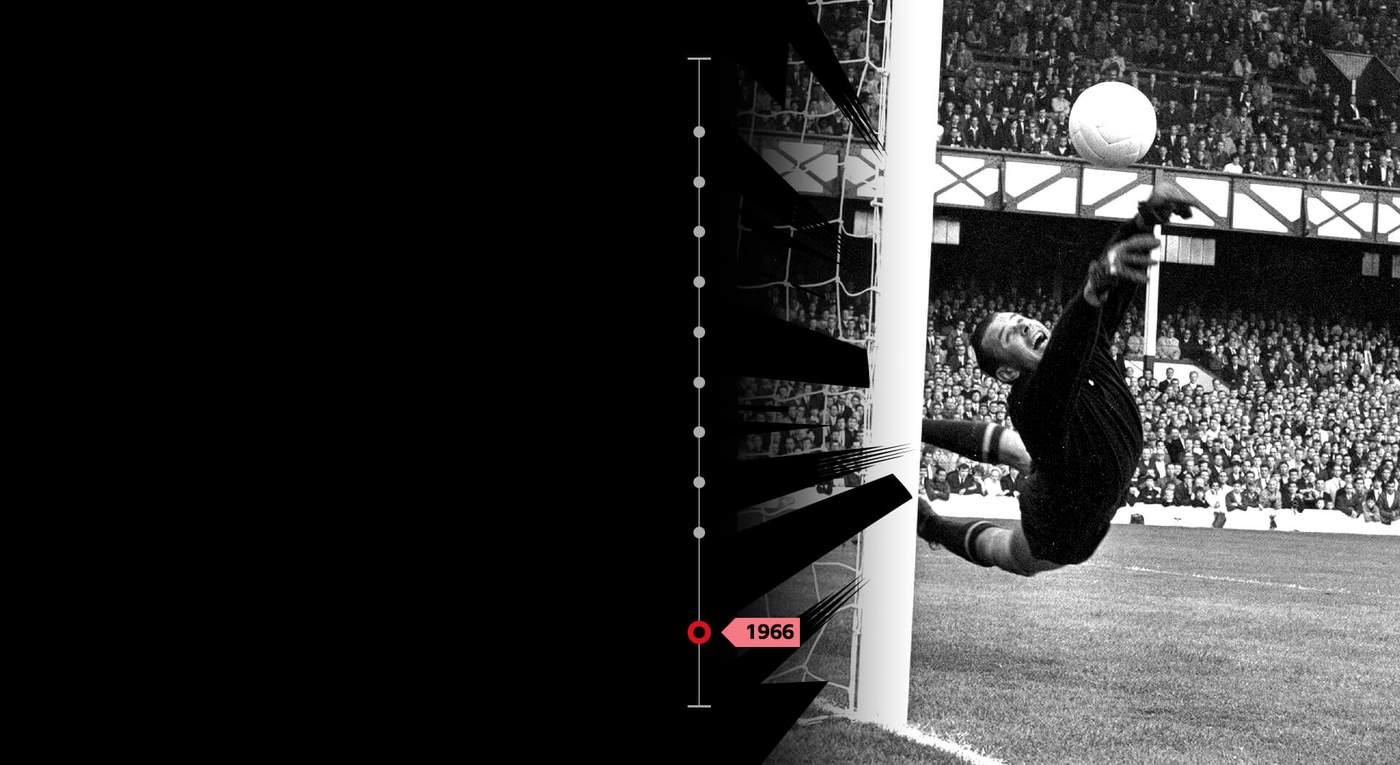

But there is one major piece missing from the collection - a World Cup medal. The best Yashin achieved on football’s biggest stage was fourth place at the tournament England hosted and won in 1966. In fact, despite revolutionising his position - and despite receiving the game’s most prestigious individual accolade - a poor World Cup almost prematurely ended Yashin’s career.

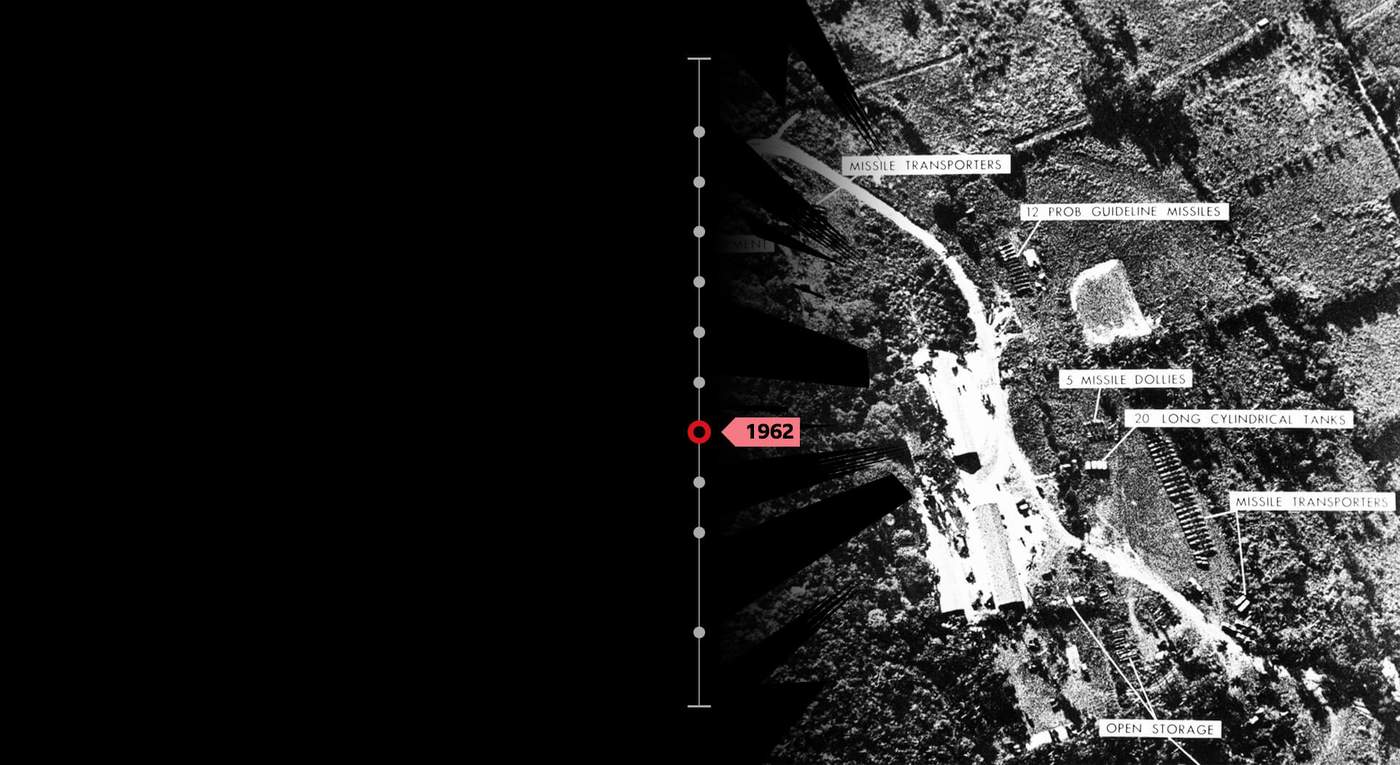

In 1962, the Soviet Union went out in the quarter-finals, defeated 2-1 by host nation Chile. Yashin, then 32, had not performed to his best. Two soft goals contributed to his team’s downfall and the single Russian language report of the game painted him as the scapegoat.

When the team returned from South America, angry supporters greeted them at the airport. There were signs reading “Yashin retire” and “Time to get your pension”. The windows of Yashin’s home were smashed, insulting messages were left on his car, threatening letters arrived in the post. He called these days the “most bitter of my football life”.

Yashin (back row, third from left) with the Soviet Union national team in 1966

How could you not take it badly?

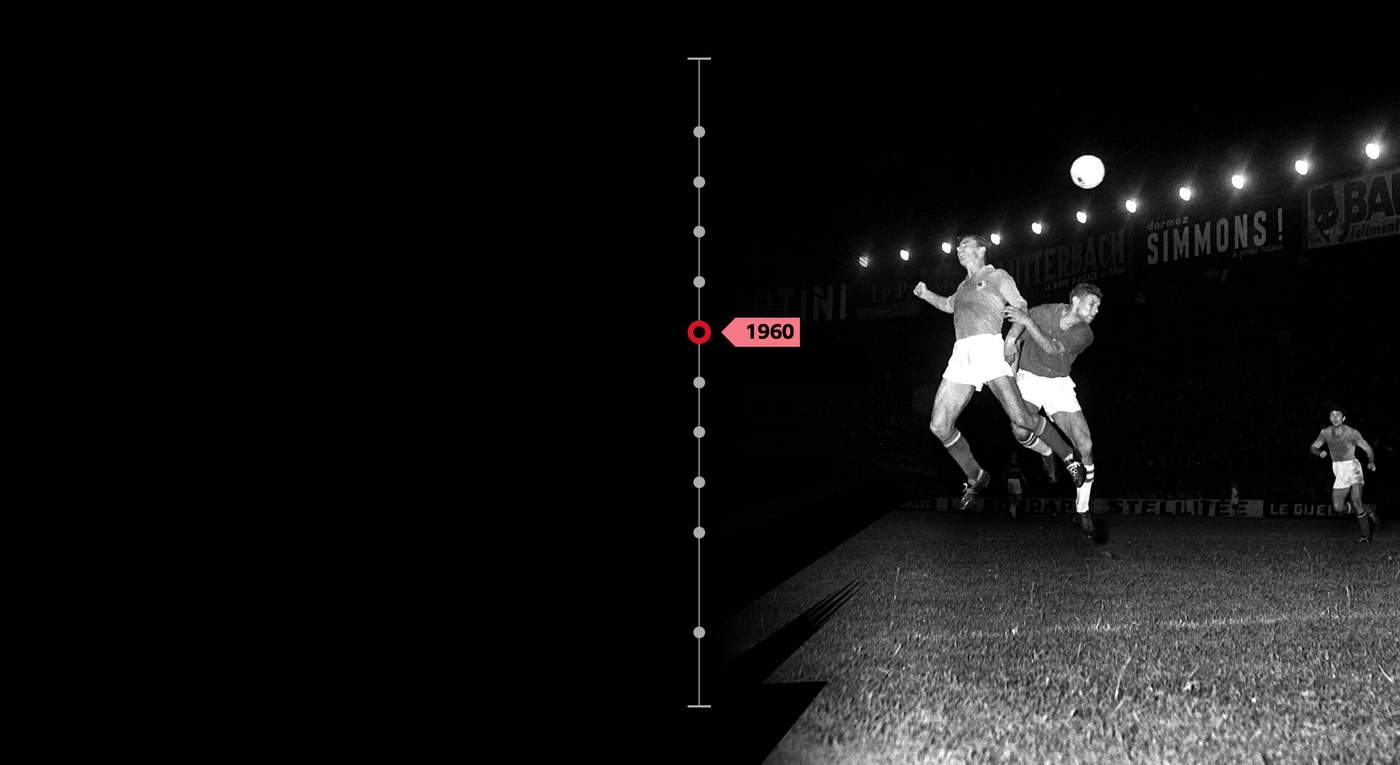

Yashin had been the hero in 1960, holding off a dominant Yugoslavia side in the European Championship final while his team-mates up the pitch conjured a comeback win in extra time. After Chile, Valentina says she had never seen her husband so down.

“He wanted to quit,” Valentina says. “When Lev came back to Moscow they were whistling in the stadiums as soon as his name was announced. There was screaming and jeering. They thought it was all his fault - that it was only him who had lost the game, not the whole team. The journalist who reported from the match did not know about sports - his job was to write about South American politics.

The report said nothing about how he suffered concussions but carried on, nothing about the rest of the team, only about Lev. They said he was sleeping and the goals flew in.”

But Yashin - a man who had built his success on hard work - found the resolve to carry on despite adversity. It was not the first time.

At the beginning of his career, while playing for his metalwork factory team at the age of 18, Yashin suffered a nervous breakdown.

In his autobiography, he wrote: “Was it depression? I don’t know. The fatigue accumulated over the years began to make itself felt and something in me suddenly broke. At that time I felt nothing except emptiness.” The future great had stopped going to work - “by law I was a truant”- and had lost his appetite for sport.

A friend at the factory team suggested he volunteer for military service. Yashin called it his “salvation” - and his big break turned out to be just around the corner.

Now combining football with his military duties, Yashin rediscovered his love for the game and began to commit to training far more seriously. He was soon spotted by Arkady Chernyshev, a Dynamo Moscow youth coach and former football and ice hockey player. By 1953, four years after being signed up, Yashin had become a trusted member of Dynamo’s senior squad.

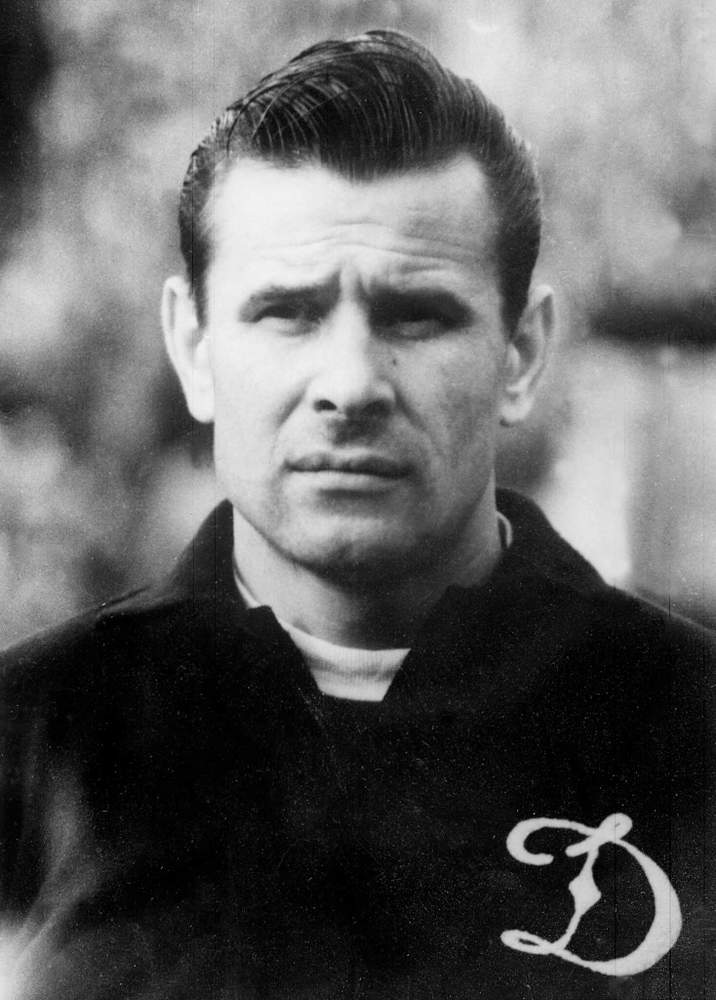

Yashin was voted the best goalkeeper of the 20th century by the International Federation of Football History & Statistics

He was also a talented ice hockey goalkeeper and lifted the Soviet Cup in March 1953. It was his first major silverware - although the football version followed in October. Yashin had thrown himself into both sports at elite level, before permanently siding with the game he loved most of all in 1954. He would be a part of four World Cups, help win his country’s first two major titles, save a record 150 penalties and see his reputation grow to the status of an international icon.

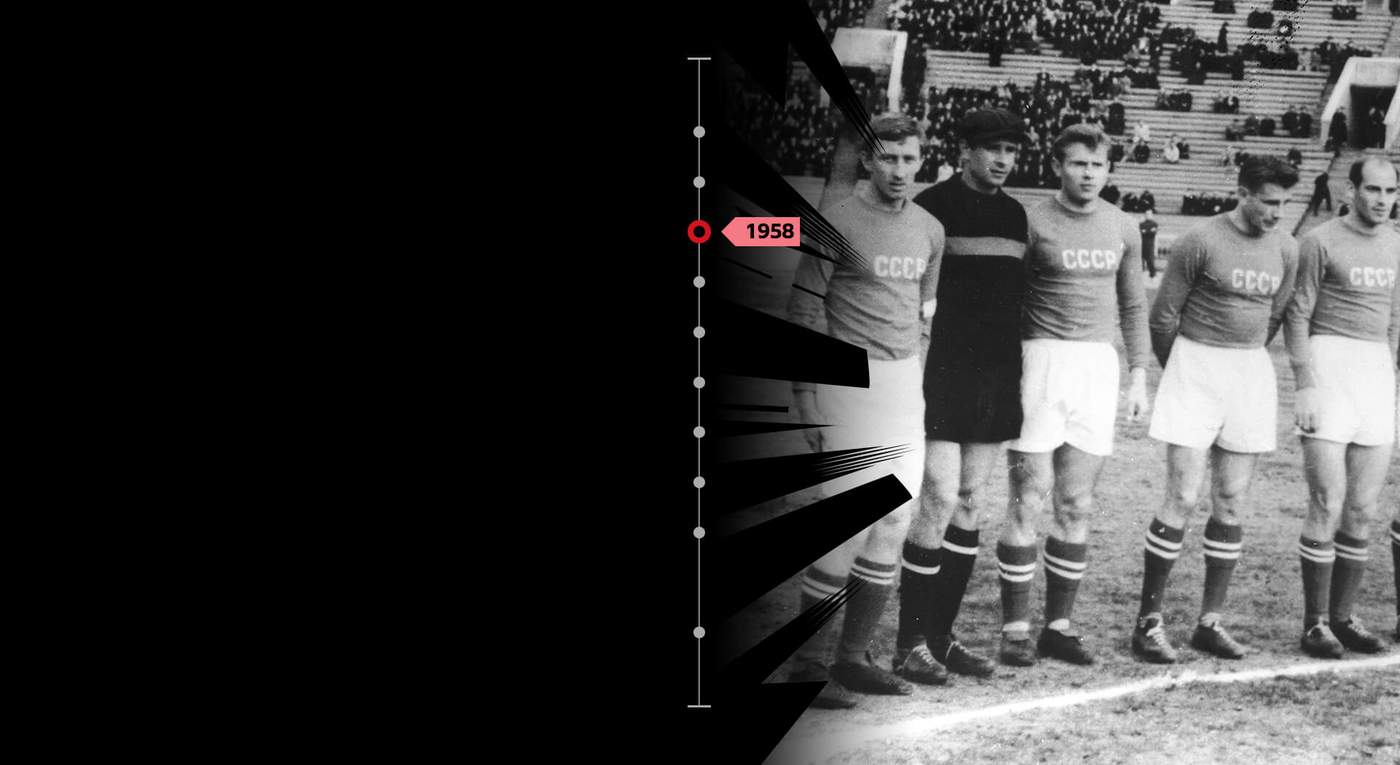

Yashin was known for his sportsmanship, his modesty and his imposing stature at 6ft 2in. Former England forward Sir Tom Finney, who died in 2014, recalled taking a penalty against him at the 1958 World Cup. He said: “I decided to use my weaker foot because I knew that he'd have seen me strike a few penalties with my left. Was I nervous? You bet! When I turned round to begin my run-up, some of my team-mates had their backs turned. They couldn't bear to watch.

You can imagine how I felt, but I scored! I had outfoxed the great Yashin!”

Valentina remembers well the day her husband proved those who had doubted him after Chile wrong.

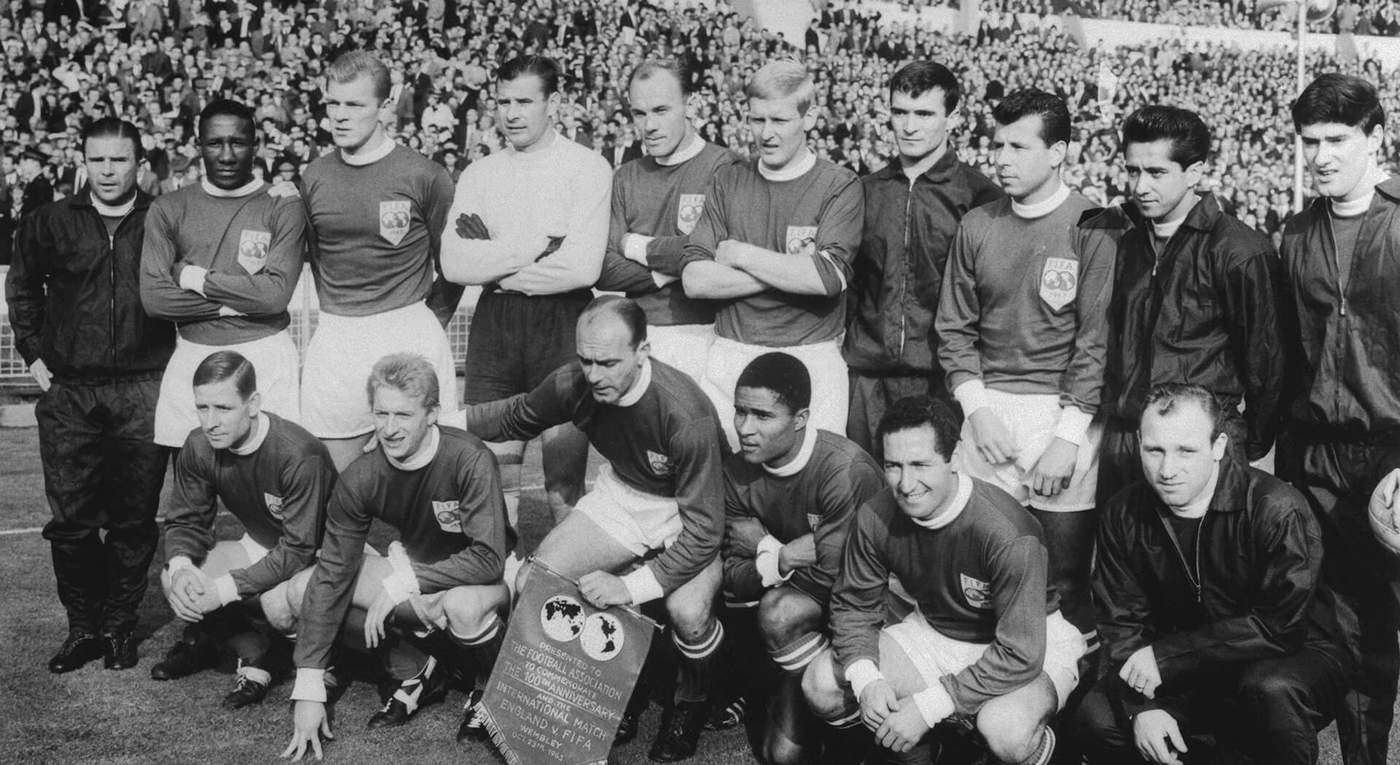

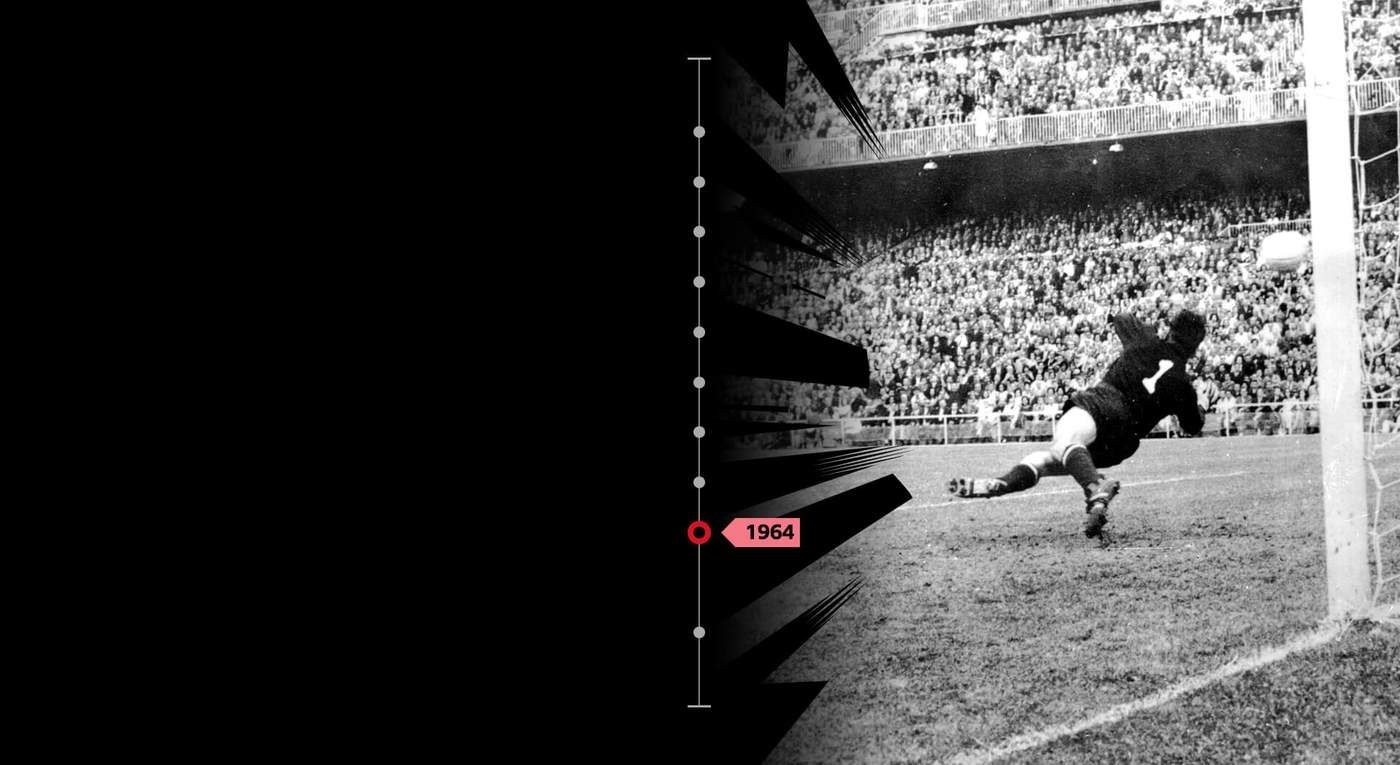

It was 23 October 1963 and Yashin was in London, playing at Wembley for a Rest of the World XI against England in a special game organised to celebrate the Football Association’s 100th anniversary. She was working as a radio journalist and watched the match on a big screen at the central radio committee building in Moscow.

Yashin had been selected by the World XI manager Fernando Riera, whose Chile team had knocked out the Soviet Union a year before. He played one half and made several outstanding saves. It was 0-0 at the break and Yugoslavia’s Milutin Soskic replaced him for the second half. The match finished 2-1 to England thanks to Jimmy Greaves’ 90th-minute winner.

Valentina recalls being on her way home in a taxi, having picked up their daughters from school and nursery. “The driver said to me: ‘Did you hear about the game in London? Our team came out on top,’” she says. “‘What do you mean,’ I said back to him. ‘It finished 2-1.’ ‘Oh, that doesn’t mean a thing. Yashin played the first half - the score was 0-0 when he came off.’

“That's what the reaction was like in Moscow. All the fans were celebrating him again.”

In December of 1963, Yashin won the Ballon d’Or, which is still given annually to the best player in the world. That season, as Dynamo won a fifth league championship with Yashin in the side, he had produced one of his best campaigns, conceding seven goals in the 27 games he played.

Valentina says they didn’t do anything special to celebrate - reluctantly she concedes they might have eaten a special dinner at home, though nothing too fancy - but Yashin’s reputation was restored.

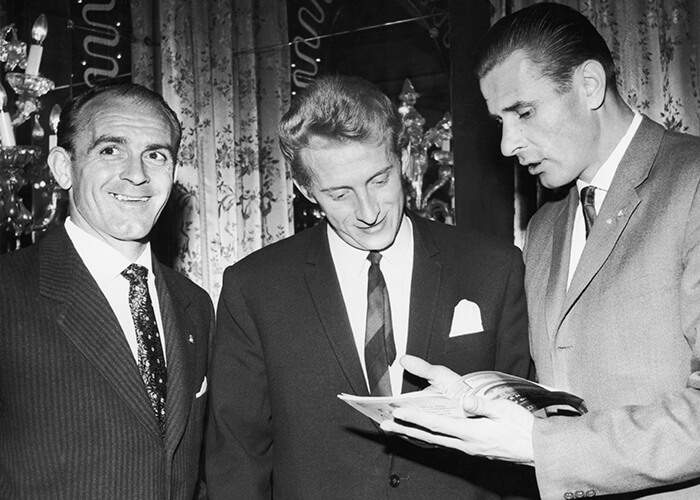

Left to right: Alfredo di Stefano of Argentina, Scotland's Denis Law and Yashin at a dinner at the Cafe Royal in London on 23 October 1963

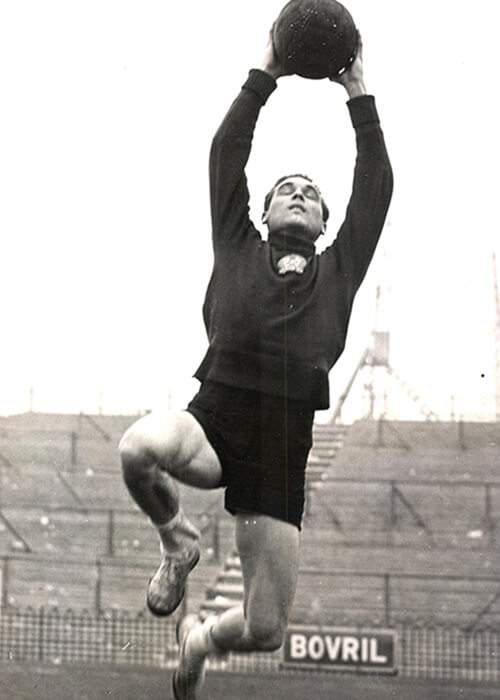

France Football - the magazine which still presents the Ballon d’Or - wrote that Yashin had “revolutionised the role of goalkeeper like no other before him, by always being ready to act as an extra defender” and by “starting dangerous counter-attacks with his positioning and quick throws”.

We might recognise the same in Manuel Neuer’s ‘sweeper-keeper’ role for Germany’s World Cup-winning side of 2014. Other innovators may have influenced him on the way - especially the Hungarian Gyula Grosics - but no goalkeeper captured the imagination quite like Yashin. The opening lines of a Yevgeny Yevtushenko poem written about him read: “Now here’s a revolution in football/The goalkeeper comes rushing off his line.”

Gyula Grosics

His individual place in history was assured. Today, it is his face, his flat cap, his outstretched dark sleeve on the poster for this summer’s World Cup in Russia. Yashin is a player who has passed into legend - even though his iconic hat was stolen, lifted off his head by a pitch invader after the 1960 European Championship final and never replaced (Valentina says he simply could not get used to another), and even though his famous black top was actually a very dark blue.

But Yashin was more than just a goalkeeper - he was a Soviet goalkeeper. And that has a far deeper significance than we might think. In Russia, the goalkeeper is the border - and when Yashin grew up the border was in grave peril indeed.

Valentina says: “Any mistake a goalkeeper makes, everyone can see it. They remember it. They’ll speak constantly about it. The goalkeeper suffers a huge amount of nervous tension in every single match because they are the last line, the one on the border. If that border is breached, it’s a goal.”

Yashin’s wife recalls the restless nights he would spend tossing and turning in bed as he agonised over a deflection that had spilled through his gloves, or a powerful shot he could not quite reach. Even if they had won the game, she says, it would be the same - because one slip is always one too many.

Yashin is believed to have kept over 270 clean sheets during his career

That is why the goalkeeper is a unique position in football, and in Russia the role carries an extra special significance. Valentina is not alone in comparing the goalline with the border.

Another to do so is the artist Aleksandr Rukavishnikov. There are many monuments to Yashin in Moscow, including two bronze works made by the celebrated sculptor.

Rukavishnikov is not a football fan, but he is a Yashin fan. Why? “He is a national hero - not only because of football but also because of his character, [because] of what a wonderful man he was.

He is a symbol of our greatest successes. He is a goalkeeper, and the goalkeeper is like the border. The defender of everything.”

When Yashin was a child, that frontline had been overrun; the borders had been breached.

Born in 1929, he was evacuated from Moscow with his family in autumn 1941 when the Nazis were just 70km away from the capital. St Petersburg - Russia’s second city, then called Leningrad - had been surrounded and food was already running short.

Between July and December 1941, the Nazis advanced into Russia, coming within just 70km of Moscow

That siege - the deadliest in history - would last 872 days and some 750,000 citizens would die. People boiled leather belts into soup, anything to survive. There was cannibalism. Even the mice starved - those that were not caught and eaten.

In his autobiography, Yashin wrote that his “childhood ended” at the age of 11 when he and his family arrived in Ulyanovsk, about 800km east of Moscow, chosen as a safe place to relocate the munitions factory where his father worked. By the time he turned 13, Yashin was working there himself, making bullets.

He wrote: “Girls and boys of my generation waited in line for bread, dreamed of victory on the front and a spare piece of lump sugar. We had to make sacrifices long before our time.”

They dragged the machines through the snow, rebuilding the factory out in the open. Food came from a nearby village, hauled 12km home on the back of a sleigh.

Eventually, the Nazis were driven out. By 1944, it became clear the “happy rumours of victory at the front spreading in the camp” were more than just hearsay and Moscow was deemed safe once more. Yashin and his family returned home. War would soon be over.

Germans soldiers retreating to the west by horse and cart on a snowy Soviet road in 1944

“In war, we received an experience that no course will ever be able to teach,” he wrote. “We were taught how to work - not out of fear or for promises, but to work for one's conscience and to work oneself to the bone. When we were competing for championships and titles, we weren't thinking about the rewards victory might bring, but were happy instead just to be able to play football.”

In other nations, you might find that the most revered footballers play further up the pitch. It could be the midfield schemer, the mercurial number 10, or the wily, sharp-elbowed centre-half. Yashin was a goalkeeper - the ultimate protector, the last line of defence.

The largest country on the planet is a complicated place - beautiful, damaged and proud. But the experience of war, a history of repelling foreign invaders, partly explains the special role of the goalkeeper in Russia.

Take a trip to Moscow’s Tretyakov gallery and you will see Aleksandr Deineka’s 1934 painting The Goalkeeper, a heroic body flinging itself towards the ball. Or there is the 1949 work by Sergei Grigoriev, in which a young boy with a bandaged knee and stoic frame crouches, ready to protect his makeshift goal on broken ground. Its title? The Goalkeeper.

In the 1936 Soviet film The Goalkeeper, the hero saves the day with a penalty stop and even scores the winner himself against a fictional international team clad in all black, resembling some kind of fascist enemy. A musical comedy, its final song contains the lines:

Hey, goalkeeper, get ready for battle. You’re a watchman by the gate. Imagine that behind you, the frontline lies in wait.”

Yashin rose from humble beginnings, through suffering and sacrifice, to become a giant of the 20th century game, and he shone brightest during a time of extraordinary Soviet achievement.

But the end of his life was marked by tragedy and terrible health problems. Despite severe illness, resting on crutches following a leg amputation, the great goalkeeper would address his admirers one final time. It happened when the Soviet Union itself was close to collapse.

Yashin was 41 when he stopped playing and, as Valentina says, “41 years is a lot”. “I remember in one of his final games, he landed after trying to dive for the ball and was just lying there. I thought: ‘Can it be that he’s hurt?’ He had concussion three times, he was in hospital for three days each time and I thought it was concussion again.

“He was lying there and didn’t get up. But then reluctantly he rose and went back into the goal. He threw the ball up the pitch and everything was OK. I asked him at home: ‘Why didn’t you get up? I was worried. People around me were worried.’ He said: ‘I didn’t want to too much. The cut grass smelled so nice, I really didn’t want to get up at all.’”

During our time in Valentina’s living room, the phone rings three times - she is in demand. A Russian documentary journalist wants to know whether the title of their programme should be Yashin: The Legend or Yashin: The Hero. Very little time of day is given to that particular caller.

Valentina Timofoeevna Yashina

We have been talking a long time, but about a whole lifetime. About how she had at first been reluctant to marry despite repeated proposals, eventually giving in at a chance meeting in a Moscow shop. About his final years, which were dogged by terrible health problems, his leg amputation, his two heart attacks and his two strokes. About how his lifelong friends from the Moscow factory he had worked in made him a sleigh so he could still go ice fishing with them in the winter.

Yashin spent much of his retirement indulging in what Valentina calls his second passion: fishing. But health was always a problem. Even during his career he had suffered from chronic stomach pain that Valentina blames on his wartime upbringing and the poor food. He remained a heavy smoker throughout his life - he found he could not stop, having started when he was about 13.

“I supported him as I could, but any person is not so happy when they’re in pain,” Valentina says. “Health is health. Football, it's a sport - and sport is work, hard work. He was a little gloomy sometimes. It was hard for him to walk, that was the first thing. Then there was the stomach, the heart attacks, the strokes. Of course it affected him - but no, he did not change.”