Three years ago, thousands of babies were born with brain damage in Brazil, after their mothers contracted the Zika virus during pregnancy.

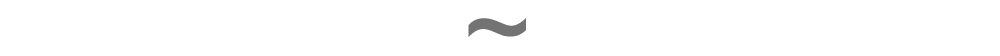

Their most prominent symptom was microcephaly - abnormally small heads.

While the Zika crisis was at its height, I learned that my own baby girl, Katy, had microcephaly too.

Over the next few years, as she grew into a toddler, I often thought about Brazil’s Zika babies. I wondered how they were developing and how their families were coping.

This spring, I went to Brazil to find out.

Two little boys are sitting cross-legged on mats in a brightly lit room filled with noise in Recife, north-eastern Brazil.

Supporting each child is a grown-up in a blue coat. A third strums out a samba song on guitar.

With help, one of the boys, Guilherme, is able to beat a drum in time with the music. But his little friend Daniel is unable to lift himself out of the arms of his attending therapist. Daniel smiles as he listens to the song, then nods off.

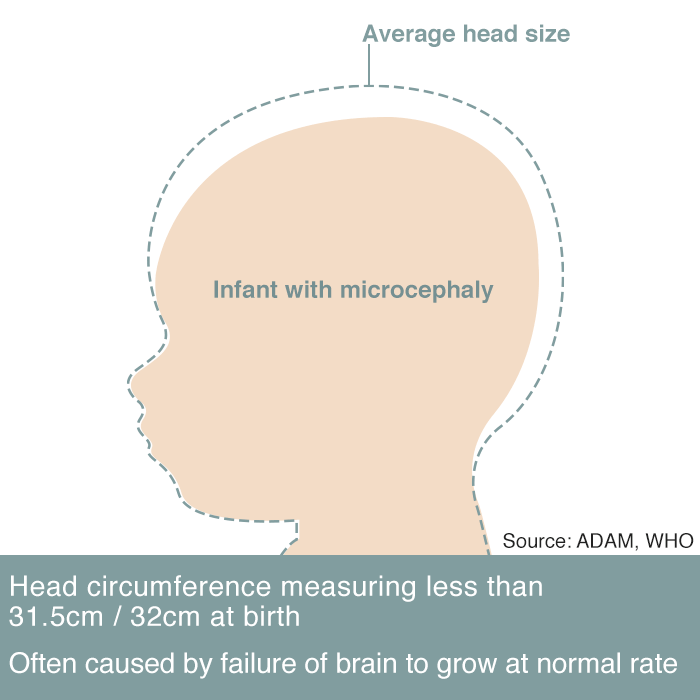

Both boys are growing up with congenital Zika syndrome (CZS), a set of physical impairments caused when their mothers were infected with the Zika virus while they were pregnant. In Brazil, more than 3,000 children were born with CZS, following the outbreak in 2015 and 2016.

The most well-known symptom is microcephaly – abnormally small heads. Three years ago the world’s news outlets were filled with pictures of screaming newborns, their heads so small that their scalps folded into a mass of wrinkles.

Guilherme didn’t look like that, exactly. But since he was born at the height of the Zika outbreak, his mother Germana Soares insisted doctors run some tests on her boy.

“The tests took a while to come back and when they did the doctor gave me the news in the worst manner possible, that is, with a bunch of predictions,” recalls Germana. “He’s never going to walk, he’s not going to survive more than a year, things like that.”

Guilherme cannot walk – yet – but he has exceeded many expectations. I watch as he is strapped into a web of bungee ropes and begins to bounce joyously up and down, a treatment known as spider therapy.

He also has a few words – “No!” definitely seems to be one of them – and when he gets the chance he grabs my microphone with surprising dexterity and strength.

“He has a really strong personality, he is very strong-willed,” says Germana. “He knows what he wants and when it’s a no, it’s a no.”

Maybe these character traits come from his mum. After the initial shock of Guilherme’s prognosis, Germana did more research about the challenges that lay ahead. She learned that her son would be much slower to develop than his peers.

“But I had been trying to have a baby for six years and I just wanted to have my boy,” she says. “So, I brought him home and dived into the world of having a disabled child.”

She soon started a WhatsApp group with other mothers she met at Guilherme’s numerous medical appointments. This evolved into a support network called the United Mothers of Angels, or UMA.

More than 400 women belong to this Zika sisterhood. They refer to one another as guerreiras, or warriors, and Germana is their indomitable leader.

After Guilherme’s physio session, I watch as she wheels him on to a bus paid for by the state government to take them home. I ask if all the Zika mums have access to this service.

“No, I am one of the only women that have access to this,” she says. “It’s because I am the leader of the association, I am very outspoken and a thorn in the side of the authorities.

“They think if they give me this service I’ll shut up, but I think if they can offer it to me they can offer it to everyone – and it’s not going to shut me up.”

Back in 2015, when I was coming to terms with my own child’s diagnosis of microcephaly, the Zika mums of Brazil were portrayed as grieving victims of an uncontrollable disease. But three years on, the outbreak is over and it’s these women who are proving uncontrollable.

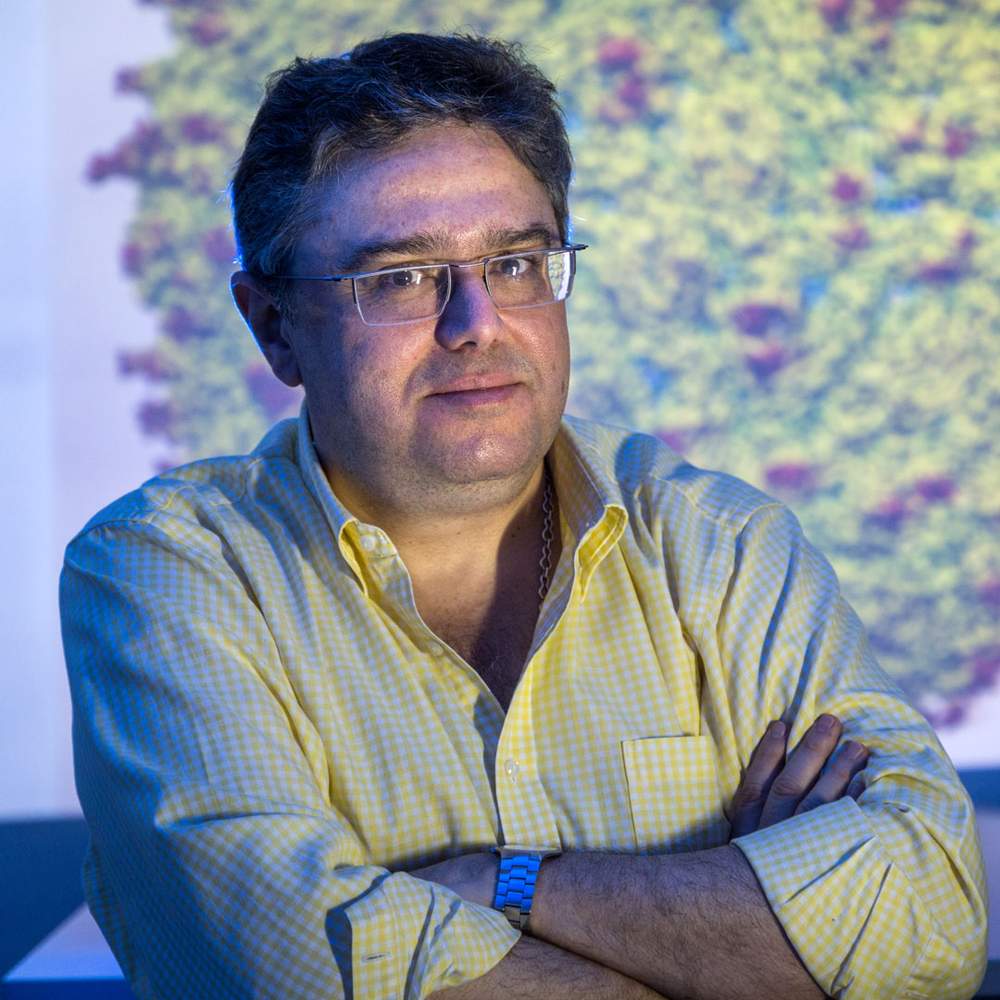

Germana’s son Guilherme came under the care of Dr Vanessa van der Linden, the paediatric neurologist credited with first spotting the trend of microcephaly in Recife.

Her first CZS case was in August 2015. The CT brain scans indicated a congenital infection, but the lab results came back negative for the usual suspects: toxoplasmosis, HIV, rubella and CMV, a common virus that can cause disabilities in babies. So Dr Vanessa – Brazilians like to call doctors by their first name – set to work investigating a genetic cause.

But then she started seeing other microcephaly cases in her public hospital in Recife. On 14 September, she saw three babies with the condition in one day. Typically she saw babies like that once every two or three months.

“Most congenital infections are sporadic,” she says. “So we needed to think of a new agent that can cause an infection, like an epidemic.”

Dr Vanessa notified Recife’s health secretary, and asked for financial support to step up her investigations. She also phoned another paediatric neurologist whose opinion she valued: her mother, Ana.

“I said, ‘Mummy, I think there is something strange. I think there is a new disease because I saw a lot of patients in two or three weeks with microcephaly and congenital infections.'

“Two days after that she called me back. ‘Vanessa, I think it’s true because I had seven patients with microcephaly on the same day.’”

A few weeks later, her brother Helio – another neurologist in Goiania, over 2,000km away – WhatsApped Vanessa some infant brain scans. He was seeing the same thing.

Much to his colleagues’ amazement, Dr Helio immediately notified the city’s health minister, and in time that child was identified as Goiania’s first congenital Zika case.

Many of the mothers told Dr Vanessa that they'd had a rash during their pregnancy. It was just like dengue fever, they said, except the test for dengue came back negative.

We now know that the Zika virus infects and kills radial glia – the cells that go on to become neurons in the brain.

There is only so much a neurologist can tell a parent about their child based on an MRI brain scan. But in those first black-and-white images of the Zika babies, Dr Vanessa saw hints of what was to follow.

The frontal lobe was most badly affected, and this has serious implications for motor function. Now all 130 of her Zika-affected patients have problems with movement.

The cortex was also badly affected and the neurons leading to the white matter in the brain had calcified. This suggested epilepsy. Sure enough, two-thirds of her patients experienced seizures in their first year - double the frequency of a comparable group of children with cerebral palsy. She now believes that about 90% of her CZS patients have epilepsy.

Beyond these similarities, though, the children affected by Zika are a mixed bunch.

About 60% of Dr Vanessa’s CZS patients have profound and multiple learning disabilities, but some don’t seem cognitively delayed at all. Some patients engage well with the world, others seem autistic.

And while some children have small heads, others don’t have microcephaly, but hearing and vision impairments or spasticity in their limbs.

The Zika babies – whose many stories all became the same story, of the crisis, the outbreak – are emerging as a diverse and fascinating group of toddlers.

In early 2016, Maria Carolina became the third child in the city of Petrolina to be born with microcephaly.

“People were curious about her,” recalls her mother, Leticia Conceicao da Silva. “When I gave birth, the room was full. Everyone wanted to see her, to take a look at her.

“There were other mothers who didn’t want to share a room with us. They would say that my child was weird, that she looked like an animal.” The nurses drew a curtain around Leticia and her baby.

That first day of Maria Carolina’s life set the tone for the next few months, as mother and daughter learned to cope with two contradictory pressures from society: to cover up and to submit to the gawping of strangers.

A reporter from the local paper called up. “They wanted to spend the day with me and with her so they could understand what our life was like,” Leticia says. “But I turned them down, because I realised that they just wanted to sell more newspapers by exploiting my daughter.”

She loathed the tone of the reports she saw on TV, in which microcephaly was presented as a ghastly abnormality instead of a well-understood medical condition. Crass remarks about the Zika babies abounded – they were strange, they were ugly, they looked like E.T.

At the same time Leticia struggled with a crisis of confidence. She had raised four other children, but how would she cope with this unexpected burden?

Slowly, with support from a counsellor, she came to the conclusion that she would do it in more or less the same way.

As we talk, Leticia feeds Maria Carolina some porridge. She is in good health and eats well.

Leticia hopes that one day Maria Carolina will walk and talk like her older brothers and sister.

“That is my dream and I think it is hers too,” she says. “Because when she sees her siblings playing around, she gets anxious and excited, she wants to do the same things.”

We are talking in a health centre in Petrolina, where seven or eight families have gathered together.

On the floor next to me a physiotherapist is working with a little girl called Maria Luiza.

He bends her over a Swiss ball while a large white dog licks her back, stimulating her muscles.

I am surprised to see such esoteric therapy on offer in Petrolina. The city is 500km from the coast, in an isolated, impoverished region known as the sertao.

But I learn that more conventional therapies are also available. Both Maria Luiza and Maria Carolina go to different kinds of therapy two or three times a week – a rate that compares favourably to the special needs families I know in the UK.

Not everyone can make it to such services. The Brazilian government says 70% of children with CZS have received some form of specialist treatment - which suggests that almost 1,000 children have been left without.

Maria Luiza’s mother, Rafaela Coelho Araujo, feels differently about the news coverage of Zika in 2015 and 2016. Her child was not diagnosed with microcephaly at birth and it was only when Rafaela saw a news bulletin that she understood her child had the same condition.

“I used to like watching the news because I would learn from it,” she says. “I understood that it wasn’t happening just to me, there were other children in the same situation as her.”

However, like Leticia, Rafaela struggled to cope with the prying eyes of strangers. Then one day, her counsellor suggested that if she found the staring hard to deal with, she cover her child up. Rafaela considered the suggestion.

“I thought to myself: 'Why ever would I hide my daughter?' So I started to go out with her in public and people would look at us. I would look back at them with a smile on my face.

“They would ask me if she was ill. I would say she just had microcephaly. Sometimes I would pray to God to get more wisdom about how to reply to those people as I didn’t want to sound rude. I would run out of patience - but I would take a deep breath and try to stay polite.”

The mothers I am meeting are taking part in an event organised by Germana Soares, president of the United Mothers of Angels.

She is midway through a road trip through the sertao with an educational psychologist, a sanitation expert and a social worker.

The trip has been funded – after some nagging – by the health secretary of the state of Pernambuco.

Zika-affected families are at a turning point. Many have got over the initial shock of diagnosis, and reached a point of emotional and medical stability. Their attention is now turning outwards, to the social aspects of disability: how will their children live in this world? Where will they go to school? How will they be able to fulfil their potential in society?

“Being part of UMA gave us two options – either be a victim and don’t do anything, or become a protagonist in the lives of these kids, making sure they have access to their rights,” says Germana. “Our fight is to look for a better quality of life for these kids.”

Although Brazil has equal access legislation, it is not enforced in a systematic way. The main way to make things happen is to pester the powers-that-be.

Leadership is important. Last November, Germana became the first Zika mum in Recife to secure a day-care placement for her child. Within weeks of posting this breakthrough on Facebook, another six families in the city followed suit.

As she travels through the sertao, Germana is hoping to transform the mums she meets into guerreiras. But it’s not so straightforward. Many of the women were very young when they became pregnant and are locked into traditional gender roles. Some of them rarely leave the house without their husbands.

And the culture of the sertao is steeped in old-fashioned beliefs in providence.

“Many families will say it’s up to God to cure the children and they will sometimes stop their children’s treatment,” says Germana, frustrated.

“Everyone has to play their part. God gave men intelligence to create medicine – he shouldn’t have to descend from the heavens to give it to children.”

It has been suggested that the Zika virus came to Brazil during the 2013 Confederations Cup.

To be specific, some suspect it accompanied players or supporters from Tahiti, who played a match against Uruguay in Recife on 23 June (Tahiti lost 8-0).

At that time French Polynesia was in the middle of a Zika outbreak, which spread to Easter Island, the Cook Islands and New Caledonia.

An alternative theory, recently put forward by Brazilian researchers, is that it accompanied immigrants from Haiti, or Brazilian soldiers who had been stationed in the country.

The virus was first discovered in Uganda in 1947. A common question about Zika – and a cause of public scepticism about the disease – is why no birth defects had been seen anywhere before the virus landed in Brazil.

In fact, a retrospective study, published in 2016, found 19 cases of birth abnormalities in French Polynesia that were probably linked to Zika. Around that time, it seems the virus may also have mutated to become more virulent.

But the Zika outbreak in Brazil in 2015 was the first time the virus had a chance to run amok in a densely-populated area. The virus’s favourite host, the Aedes aegypti mosquito, does not fly far. Recife has a population of 1.5 million and in poorer areas the dwellings are low-lying and close together.

Aedes aegypti mosquito

Families affected by Zika overwhelmingly come from low-income backgrounds. Recent research by the statistician Wayner Vieira de Souza shows that the prevalence of microcephaly in the poorest parts of Recife was six times higher than in the wealthier parts.

Poor people are simply more exposed to mosquitoes. They live closer to the ground, are unlikely to have air conditioning at home, and travel by bus rather than car.

More than a third of Brazilians don’t have access to a constant supply of water, so they keep it in tanks – and the Aedes aegypti mosquito likes to breed in clean, still water.

In December 2015, the Brazilian government deployed 220,000 soldiers to go door-to-door with health inspectors in Recife and other affected parts of the country, to check whether residents were covering their water tanks.

Such efforts may have had an impact on the number of breeding grounds, but a 2017 report by Human Rights Watch was critical of the government’s focus on the domestic arena, rather than on large-scale improvements to the sanitation network.

With the responsibility of preventing Zika infection placed squarely on mothers, I wondered whether the Zika mums now felt guilty for their children’s disabilities.

Source: Brazilian Ministry of Health - Information based on notification dates by states to the ministry of health for congenital Zika syndrome.

“A certain sector of society blames women for everything,” says Germana Soares. “The government was irresponsible because the mosquito should have been controlled.”

She says the Brazilian government needs to account for what happened by paying families affected by Zika compensation in the form of a monthly stipend. She and other activists have teamed up with a sympathetic MP, who is pushing for legislation to give the women 5,000 reais ($1,200) a month for life.

“This is separate from disability benefits,” says Germana. “This is the government acknowledging there was an epidemic.”

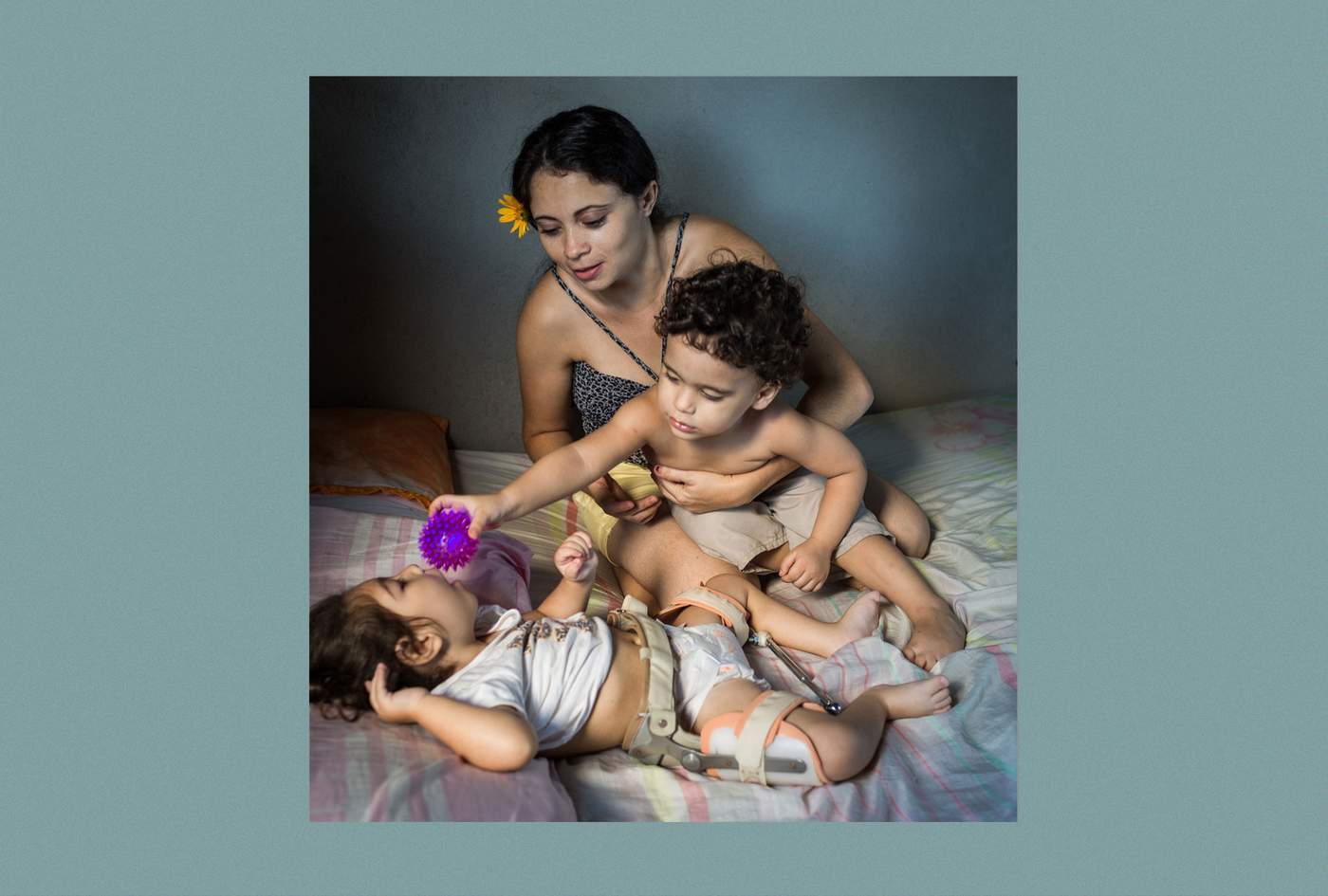

Melissa Vitoria Severina was born with a head circumference of 26.5cm. The average for baby girls in Brazil at full term is 34.5cm

Now, at two years old, she has a pretty heart-shaped face and glistening brown eyes. She has an obvious visual impairment, but listens attentively to the world around her. When I reach two fingers towards her, she grabs them in her fists.

My daughter is exactly a year older, and Melissa Vitoria reminds me powerfully of how she used to be. She is wearing a brace to keep her legs separated following recent hip surgery, but her mother Cassiana carries her awkward bundle with ease.

Meanwhile, Melissa Vitoria’s twin brother Edson Miguel jumps around, trying to get his mother’s attention. Unlike his sister, he doesn’t seem to have been affected by Cassiana’s Zika infection at all.

“Melissa has a wheelchair but it stays in my mother’s house,” says Cassiana. “Because he always wants to play with it, and ends up breaking bits off it.” Edson Miguel weighs 13kg (28.6lb) his sister weighs just 7.5kg. Cassiana says she can’t afford to pay for the fortified milk powder her daughter needs.

She lays Melissa Vitoria on her bed to do some physio exercises. She extends her daughter’s arms and gently taps her wrists to encourage the fists to open. One by one, Cassiana extends the fingers to accompanying whimpers from the little girl.

After the twins were born, prematurely, in January 2016, Cassiana didn’t want to hold them.

“The doctor said that was a shame,” she recalls. “I was crying a lot, I wasn’t well. I felt such deep anguish. I was overcome by negative thoughts, of doing bad things to the children.”

She remained in hospital for three weeks. On one occasion when Melissa wouldn’t stop crying, Cassiana began to squeeze the baby girl. Someone saw what she was doing and the next day a psychologist came to talk to her and her mother.

“Since then my mum has really helped me to look after Melissa,” says Cassiana, speaking quietly, with a nervous smile. “For two months after I left the hospital, I still wanted to give the babies away - but my mum refused.”

Things improved after Cassiana was given anti-depressants. She no longer takes the medication, but happiness remains elusive - she feels numb.

“It is bad to live without emotion,” she says. “I look for it, but I can’t find it."

She blames herself for Melissa’s disability, saying that she had wanted to hold off getting pregnant for another year, but her husband pressed her to start a family. She should have listened to her instincts, she says.

Her husband is unemployed, but he is often out of the house. Cassiana doesn’t trust him to look after the children anyway. Since she doesn’t work either, the family gets by on the single minimum wage they are entitled to for caring for a disabled person, worth 950 reais a month ($230).

Six days later, we meet Cassiana and Melissa again, at an eye appointment at the Altino Ventura Foundation, a charity that has diagnosed 285 cases of congenital Zika syndrome.

Of these, the organisation is involved in rehabilitation work with 161 children – the rest are on a waiting list. It’s an agonising funding gap for parents and doctors, since early intervention strategies become less effective as children get older and their brains lose plasticity.

“We feel so sorry and frustrated,” says the organisation’s president, Liana Ventura, “We could do so much more for these children if we had more help.”

Cassiana arrives, pushing Melissa in the wheelchair so coveted by her brother. She relays the week’s main drama. The previous day – the same day that her daughter underwent a brain scan – Cassiana was in her kitchen when she heard a cry from the red clay path that runs alongside her house. “Mummy, snake! Mummy, snake!”

Rushing outside, she saw her son playing with a black snake. “I was completely desperate, not knowing what to do, because I was at home alone in the house,” she says. “So I grabbed a knife and cut the snake in two and the two bits were squiggling around.

“He doesn’t stop, he’s very active – he’s very different from my little girl. He has enough energy for both of them.”

Melissa is called in to see the doctor, a visiting eye specialist from the US, Dr Linda Lawrence. Nearly all children with congenital Zika syndrome have problems with their vision. The disease impacts both the mechanics of the eye and how images are processed in the brain.

The doctor waves a paddle displaying a line drawing of a face in front of Melissa. “We’re looking to see if she can process the contents of a human face, especially the eyes and the mouth,” she explains. “It’s a higher cognitive visual skill.”

Despite her crossed eyes Melissa fixes her gaze on the face and smiles. The doctor is impressed. “She’s trying to figure it out, she’s trying to understand – and that’s a really good cognitive skill,” she says.

Cassiana’s children are not the only twins affected differently by the Zika virus.

Doctors know of another five such cases in Brazil, which include Vanessa van der Linden’s very first Zika microcephaly patient, from August 2015.

Doctors are interested in these twins because they still don’t understand why the Zika virus affects some babies more than others. Not only is the range of disability very wide, but 94% of babies whose mothers contracted Zika during pregnancy were born without any apparent impairments at all (though a further 8% developed problems in their first year).

Part of the reason is certainly the gestational age at the point of infection, with women who caught Zika in the first trimester at greater risk of having babies with more severe disabilities. But this is not always the case, and there must be other factors.

The viral load at the moment of infection might be one. Another could be the patient’s genetic profile – maybe some people have a built-in defence against the virus. Since Melissa and Edson are non-identical this could explain the differences between them.

The Brazilian geneticist Mayana Zatz harvested neural progenitor cells from three sets of non-identical twins where, like Cassiana’s children, only one seemed to be affected by CZS. Then in the lab she infected the cells with the Zika virus.

In each case, the virus replicated more quickly in the twin with microcephaly, which seems to confirm there is a genetic element to how babies respond to the virus. The finding is significant, because in time governments may be able to identify populations that are more susceptible to the disease.

However, it is unlikely that Cassiana will ever know the full explanation for her daughter’s disability. The difference between her children may simply have been caused by the physical characteristics of their placentas – maybe Melissa’s had a weak spot which allowed the virus to enter.

Or maybe, says Dr Ernesto Marques at the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation in Recife, it was just a matter of timing: Cassiana caught Zika, passed it on to her daughter, then built up an immunity to the disease that protected her son.

But he adds that the true picture may be even more complex.

“I would say although one of the kids doesn’t have microcephaly or perhaps doesn’t even have any hearing or visual problems – I am still concerned about that kid. And I think we should keep following him - I’m sure the mother will."

Recent experiments with Zika indicate that there may be further problems ahead.

“We don’t know what other kinds of cognitive development impact Zika could have. Maybe it’s not as severe as the other one – but some impact still could exist.”

For scientists, Zika remains an intriguing mystery. But for people directly affected by the virus the science is confusing and highly dubious.

The interplay of co-factors means that a mother may experience no symptoms of Zika during pregnancy but give birth to a very disabled child. At the same time she may know other women who had rashes and fever while pregnant, but whose children seem fine.

So it shouldn’t be a surprise that many of the families I meet in Brazil do not believe Zika was responsible for their children’s disabilities, but instead put their faith in a variety of conspiracy theories.

One of the theories is that the birth defects were caused by an out-of-date batch of rubella vaccines that were distributed across the north-east. Another is that the larvicide sanitation agents put in people’s water tanks to stop the Aedes aegypti mosquito breeding was itself poisonous.

Even Germana Soares believes this “poison” exacerbated the effects of the Zika virus.

“The multiple neural deformities and the way they vary – I believe it’s down to the poisoning,” she tells us. “No-one believes it was just Zika!”

Perhaps this disturbing trend is down to the way conspiracy theories spread on social media: during the outbreak, Zika myths were three times more likely to be shared than reliable news stories about the disease.

However, I know from personal experience that we special-needs parents often tell ourselves stories to explain our children’s impairments.

Especially in the early days, there is an irresistible urge to construct tenuous, far-fetched theories which explain everything. We might point the finger at other people or organisations, or it might be enough to blame ourselves through some imagined parenting misdemeanour.

We do this, I think, to give ourselves a sense of control over the situation. When it comes to Zika, there are still so many unanswered questions about the disease that a fairy tale may well be more palatable to families than half the truth.

Bruna Bezerra learned that her child would have microcephaly when she was six months pregnant.

She had never heard of the condition, so the doctor pointed at the ultrasound image and said: “You see those two little circles? Those are his eyes. And above that is just nothing.”

“Hearing that just killed me,” Bruna recalls. She wept for the whole two-hour journey from Recife back to her house in the hills around Caruaru. But when she got home her husband’s reaction surprised her. “Well, what does that change?” he asked her. “He’s still our baby.”

Baby Benjamin was born with a skull circumference of 24cm (the average for boys is 35.2cm) and his scalp was as wrinkled as a napkin in a restaurant. But his motor skills developed – by 15 months he was able to hold himself steady while being carried, and he could see and hear well. He became very attached to his father Mario, and would laugh whenever he heard his voice.

With their daughter, Mario had been awkward and stand-offish, Bruna says, but with Benjamin he was much more hands-on.

The couple had made a living sewing, but after Benjamin was born Bruna decided to study for a nursing qualification, so that she could take better care of the boy.

This was an impossible dream. Benjamin had appointments every day, and these were often in Recife. On those days, Bruna and the baby would leave home at 03:00 in the morning to get the government bus to Caruaru, then wait hours for a connecting bus to the state capital. They would get home at 20:00 or 21:00 at night.

Bruna swipes through photos of Benjamin on Facebook. Her old phone recently broke and she has lost most of the pictures she had of her son, so she is reliant on the ones saved on social media. Finally she finds what she’s looking for: Benjamin at 15 months. He is propping himself up on a floor mat and beaming at the camera.

The day after this photo was taken, Benjamin was taken into hospital in Recife. He had developed hydrocephaly, a build-up of fluid in the brain. He underwent an operation to have a valve implanted to release the pressure.

After the procedure, Bruna noticed that Benjamin’s testicles and abdomen were swollen. Doctors told her not to worry, but she knew something was wrong.

“He stopped eating, he stopped smiling, he looked like a different child – it wasn’t Benjamin anymore,” Bruna says.

Twenty-eight days after the operation, Benjamin required a blood transfusion. He slipped into a coma and was transferred to an intensive care unit at a different hospital. The following day Benjamin opened his eyes, but he couldn’t move. He had rashes on his forehead and bottom that looked like burned skin - a generalised infection, a doctor said.

He died eight days later, on 9 April, 2017. As she recalls these events, Bruna quivers with rage.

“A nurse actually said to my face: ‘Oh Mum, you know your child’s diagnosis – you know these kids aren’t going to live forever.’ I said: ‘A child could only have a few minutes to live, but you still need to look after him. That’s your duty of care!’

“You get to the hospital and they see your address – they see you are from the countryside and they assume you are illiterate and don’t know anything.”

Benjamin’s body arrived in Bruna’s village the day after his death. The family received no financial help with the burial. In fact, Bruna’s welfare payment for Benjamin was due to be paid into her bank that very day, but when she checked later on, it wasn’t there. The payments had already been cut off.

Officials in Brazil’s health ministry have pointed to these deaths as part of the reason for a slight rise in infant mortality in 2015.

“If it depended on me, I would have lived my whole life in the ICU with him, but would that have been good for him?” asks Bruna. “I think perhaps it’s selfish to want him to stay alive if he wasn’t well. He rested and maybe that was God’s will.”

But it was hard for Mario to accept. Bruna says that he shut himself off, and cried for a month. The couple disassembled Benjamin’s cot, but at Mario's insistence everything else in the nursery remains exactly as it was.

He is now working as a hospital porter – a job he managed to get with help from a doctor who Bruna met in the ICU. This doctor is also paying for Bruna to finally get her nursing qualification. “I did not manage to help Benjamin, but I would like to help other children,” she says.

So she leaves home every day at 17:00 to do the course and gets home at midnight.

She is still in touch with the other Zika mums in Caruaru, and every now and then they will call her up to see how she is doing. They invite her to their meet-ups, but she can’t bear to go.

It is thought that about half the residents living on low incomes in the affected parts of Brazil caught the Zika virus during the 2015-2016 outbreak.

This is probably why it came to an end. Once a certain number of people have immunity to a disease it stops spreading through a population, a phenomenon known as “herd immunity”.

Since 2015, cases of Zika have been reported in more than 40 countries, though none has seen an outbreak on the scale witnessed in north-eastern Brazil.

But this merciful lull in infection rates has a downside. Some experts have expressed concern that the market is starting to lose interest in a vaccine.

The French drug company Sanofi announced last year that because of changes in US government funding for its Zika vaccine the work had been “indefinitely paused”, though it could be restarted if there is another outbreak.

At least nine other potential vaccines are undergoing clinical evaluation, however, and some are in phase II trials. But there are many challenges ahead. Crucial details about how the virus operates – in particular, how it interacts with dengue – remain unknown.

Because of the obvious ethical problem with testing a drug on pregnant women, the efficacy of any vaccine will be difficult to gauge. Scientists will have to use indirect methods, and will only know for sure whether it works when it is used during an outbreak.

And there will be another outbreak.

“It’s a matter of when,” says Dr Ernesto Marques, infectious diseases specialist at the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation.

“I don’t know when – maybe 10 years from now, maybe five years from now. It’s going to happen. First it’s going to happen somewhere else before it happens here again.”

As Germana devoted her life to Guilherme and to UMA, cracks began to show in her marriage.

In the end, the arrival of the child that she and her husband had longed for over many years precipitated their separation.

Germana says that three-quarters of the women in UMA split up with their partners after having their babies.

“Instead of becoming the woman’s partner, the men become another burden, saying, ‘Oh, you don’t give me any attention, all the attention is going to him. Where is my wife?’” she says. “And they start to look for other women.”

In 2015 and 2016 it was reported that mothers of Zika-affected babies were being “abandoned” by the children’s fathers. That certainly happened, but it would be wrong to think the Zika mums had no say in the matter. I met several women who told me they took the initiative in leaving the family home.

“My ex-husband drinks a lot,” explains Francileide Ferreira, who has four other children as well as her disabled two-year-old. “He brings the wrong sort of people home and I couldn’t deal with it any more, especially with a child like this. So I decided to leave the house. Now I have to pay rent, but it’s still worth it.”

Marcione Rocha moved to Recife from Betania, a small city six hours’ drive away. “Where I lived there is no treatment for my daughter,” she says. “All the therapies, paediatricians, we don’t have them there.”

After making numerous long trips to the city, she decided to relocate permanently with her little girl, Perala, and her three other children, leaving her husband behind.

“What I left behind wasn’t too important,” Marcione says. “The most important thing is to be with her, to help her develop, to be with the four of them. It wasn’t bad for me having her – it brought positive changes to my life.”

As she speaks, she dabs blusher on to a fellow Zika mum’s face.

We are at UMA’s headquarters in Recife, and a party is in full swing to celebrate mother’s day.

The building is packed with perhaps 70 women who are getting free makeovers, massages and dental check-ups.

A lawyer arrives to advise the women about government benefits. There is also a local MP, a counsellor, and four news crews.

Germana Soares is too busy directing all this traffic to spend time with the other mums, but in the afternoon, she finally grabs a moment to have some fun. She throws herself into the middle of a raucous, selfie-taking scrum and leads the others in a chant of “We will never be defeated.”

Meanwhile, their children are in the next room, being cared for by volunteers.

Mattresses are laid across the tiled floor. A few of the children sit upright and play with brightly-coloured toys, others lie down and gaze at cartoons on smartphones held in front of them, or doze through the humid afternoon. Able-bodied siblings linger nearby or scamper about in search of amusement.

I watch the news crews go about their work. I wonder how they will put their packages together, and how I would report this story myself if I didn’t have a child with microcephaly.

Sadly, disabled babies are almost always described in negative terms – not just by the press, but by doctors and even by their own parents.

That is because impairments are identified by observing what a child can’t do, rather than what they can do. Eventually, though, the people close to a child rise to the occasion. They learn to see him or her as an individual with his or her own special needs and potential.

But when people with little experience of disability walk into a room like this one, filled with children with significant needs, they don’t see this specialness – they just see lots of children who can’t sit up, crawl, or even swallow. They only see the can’t. To them, the love of the children’s parents is noble or brave, perhaps even a little delusional. The coverage of Zika in 2015 and 2016 was predicated on this idea of families caught up in a tragedy.

Is there a sense of disappointment in learning that your child will probably never walk or talk or fulfil the other expectations you might have had during pregnancy? Yes. Is there a period of adjustment? Definitely.

But loving your child is never brave. It’s the easiest thing in the world.