Mercury's youngest volcano found

- Published

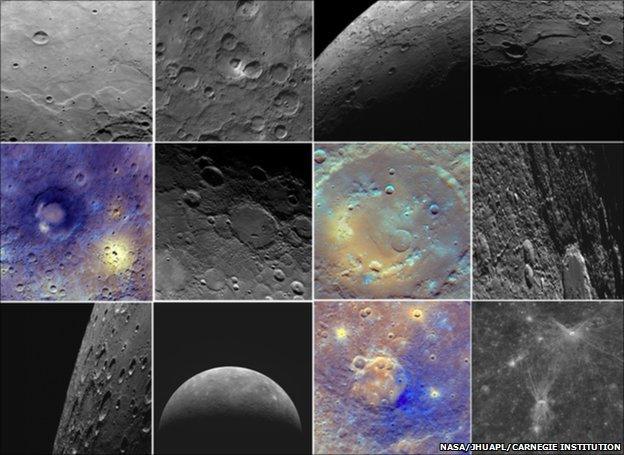

Images captured by Messenger have revealed surprising details about the planet

Scientists analysing data from Nasa's Messenger spacecraft say they have located some of Mercury's most recent volcanic activity.

This indicates that rather than being a tiny, long-dead planet, as scientists had assumed, Mercury was volcanically active for much of its "life".

The researchers say it also sheds light on how other planets in our Solar System evolved.

The findings are described in the journal Science.

The irregularly shaped depression in the centre could have been caused by a volcano

The new data have emerged from Messenger's recent third flyby of Mercury, ahead of the craft going into orbit around the planet in 2011.

This flyby revealed a basin that had been formed by a relatively recent impact. The basin has been named "Rachmaninoff".

"With the first flyby, we found evidence of volcanism all over the planet, which was pretty exciting," said Dr Louise Prockter, from Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Maryland, who led the research.

"But now we've done some age dating on this particular impact basin; it's one of the youngest on the planet and there are signs of volcanic activity [in it] that happened after the basin formed."

The age of this volcanic activity can be estimated only very approximately by examining the texture of the surface; the more overlaid impact craters, the older the surface structures are estimated to be.

Dr Prockter said: "This volcano is about two billion years younger than we would have expected. And it's possible that when Messenger gets into orbit, we'll find younger areas of volcanism.

"We want to know: was this a last gasp? Or is this more common than we thought?"

Planetary close-up

Dr David Rothery, an Earth scientist from the UK's Open University in Milton Keynes, said the findings could reveal clues about the evolution of our own planet, and even of those outside our Solar System.

He told BBC News: "Mercury is very close to the Sun, and when we're looking for planets around other stars - exoplanets - those that are closest to their stars are the easiest to see.

"So similar processes to those on Mercury might occur on exoplanets."

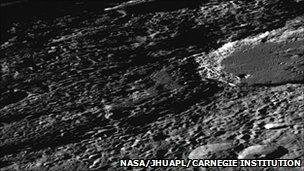

Messenger has revealed Mercury's surface in high resolution

Dr Prockter explained that, because Mercury is such a small planet, scientists would have expected it to "kick out" all of its heat very early on in its life.

The surface area of the planet is relatively large in relation to its volume, so all the heat generated underneath the surface should have escaped quickly.

Dr Rothery said: "We want to know what has kept Mercury going; it's clearly a much more dynamic planet that we expected."

Magnetic storms

In the same issue of Science, James Slavin, a space physicist at Nasa's Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, and colleagues, described evidence of very intense "magnetic substorms" on Mercury.

These occur on other planets, including Earth, bceause of the planet's magnetic field. This protects our planet from the hot, charged gas particles that flow away from the Sun as a "solar wind".

When the solar wind reaches the Earth it is deflected by the field. As a result, Dr Slavin explained, "part of the Earth's magnetic field gets pulled downstream by the solar wind to form a very long comet-like magnetic tail".

When conditions are just right, the solar wind can sometimes "load" that tail with many more lines of magnetic force to a point where it becomes unstable.

At Earth this loading goes on for about an hour before the tail's magnetic lines suddenly "break-off" - a portion return to Earth, while the rest are carried off by the solar wind.

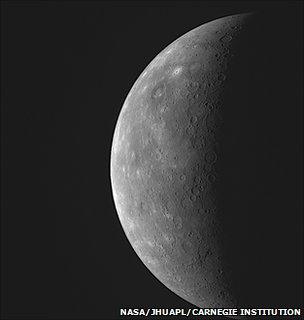

Messenger will go into orbit around the planet in March 2011

"The energy given up during this unloading drives the heating and acceleration of charged particles in the tail," explained Dr Slavin.

"This process produces the majestic auroras that can be seen in the high latitudes, as some of the charged particles rain down into the upper atmosphere."

The combined loading and unloading process is referred to as a magnetospheric substorm - it is a form of space weather that can even affect satellite communications.

Messenger flew through Mercury's magnetic tail in September 2009.

"During this third flyby, over a period of 30 minutes, we saw its magnetic tail load, and then - boom - it unloaded, a total of four times," said Dr Slavin.

"But these magnetospheric substorms at Mercury are a great surprise in that they last only about two minutes - 30 times quicker than at Earth."

Messenger's principal investigator Sean Solomon, of Carnegie's Department of Terrestrial Magnetism in the US, said: "Every time we've encountered Mercury, we've discovered new phenomena.

"Once Messenger has been safely inserted into orbit about Mercury next March, we'll be in for a terrific show."

Dr Prockter said: "The Solar System is like this giant laboratory where Earth is the control, and all the planets are different.

"Missions like this help us to understand how the whole Solar System evolved."