Red Sea coral growth 'to halt by 2070'

- Published

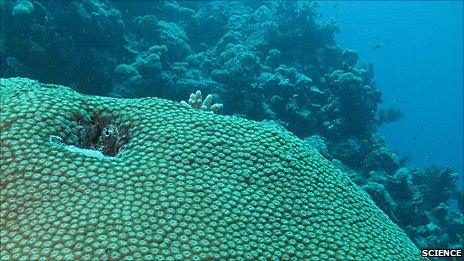

Diploastrea heliopora corals can reach a diameter of seven metres

A species of coral in the Red Sea could stop growing by 2070 if current warming trends continue, say scientists.

A team of US researchers, using 3D technology, said that the rate of growth of Diploastrea heliopora had declined by 30% since 1998.

Rising sea surface temperature was already "driving dramatic changes" in the growth rate in the important reef-building organism, they observed.

The findings have been published in the journal Science.

Co-author Anne Cohen, a research specialist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) in the US, explained that the team were able to measure the decline in growth by examining core samples from coral skeletons.

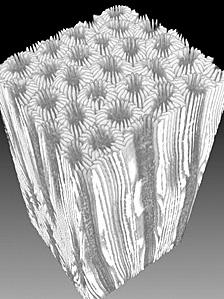

The coral's growth bands cannot be seen with the naked eye

"The coral is an animal, and the colony made up of millions of tiny, little animals - and they together build this huge thing that is seven metres in diameter," she told BBC News.

"As they are growing, they are building this calcium carbonate skeleton that the animal is basically leaving behind. If you cut through a colony, only the very top layer is actually living - the rest of it is all dead.

"What is really cool is that everything that the colony has experienced in its life, which can be very long - these colonies can live four or five hundred years - is recorded in the skeleton," Dr Cohen explained.

"It is recorded in annual growth bands, so we know exactly the year in which certain things happened."

The team collected "biopsies" from six colonies, which were then examined in a computerised tomography (CT) scanner.

"The scan reveals variations in density in calcium carbonate because the growth rings are caused by changes in density; what the CT scanner is effectively doing is revealing the annual growth bands for us, which you cannot see with the naked eye," Dr Cohen said.

WHOI used the technique because many of the corals had very complicated skeleton growth patterns, which were too complex to examine using 2D images.

Feeling the heat

By building up a profile of the growth bands, the researchers were able to see how much the coral had grown in any given year.

"We can also work out the density of the band, which tells us how much calcium carbonate the coral has put down," Dr Cohen added.

"We say in our paper, external that the upper growth rate has decreased by 30%, and the amount of calcium carbonate produced has decreased by 20% since 1998."

Using the precise chronology provided by the CT scans, the team were able to compare coral growth with the sea surface temperature (SST) record.

There was a critical temperature, 30.5C, above which the growth rate "basically plummetted".

"So we have identified a threshold temperature for growth," said Dr Cohen.

Using future climate change scenarios, the team calculated that the coral would "cease calcifying altogether by 2070", when summer SSTs were projected to exceed current summer values by 1.85C.

However, the team said this timescale was likely to be conservative.

"One reason why we say this is because we think the corals will bleach long before this," Dr Cohen explained.

"They are going to lose their symbiotic algae (zooxanthellae) long before they stop calcifying, and many of these corals will die at that point."

However, she was at pains to point out that the paper only considered the impact of rising SST on one species from the 250 or so in the Red Sea.

"It is a very important species - a dominant reef-building species - but it is only one species," she said.

"I expect that there are corals that are doing much worse than this species, but there might be others that are doing better in terms of thermal tolerance.

"Before we can talk about what the coral reefs are doing to do in the future, we really need more information about more species," she observed.

The team plans to carry out similar studies on other species. Dr Cohen said they had collected samples from another dominant reef-building species, which they were planning to examine in the coming months.