Cave yields marsupial fossil haul

- Published

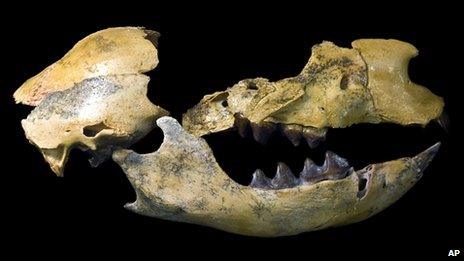

Nimbadon may have travelled in herds, say the scientists

Fossil hunters in Australia have discovered a cave filled with the 15-million-year-old remains of prehistoric marsupials.

The rare haul of fossils includes 26 skulls from an extinct, sheep-sized marsupial with giant claws.

The finds come from the Riversleigh World Heritage fossil field in north-west Queensland.

The beautifully-preserved remains have been described in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

"It's extraordinarily exciting for us," said University of New South Wales palaeontologist Mike Archer, co-author of the research.

"It's given us a window into the past of Australia that we simply didn't even have a pigeonhole into before.

"It's an extra insight into some of the strangest animals you could possibly imagine."

The giant-clawed, wombat-sized marsupial is named Nimbadon lavarackorum; researchers discovered the first of the Nimbadon skulls in 1993.

The palaeontologists have been stunned at how well preserved the fossils were - and by how many were found.

Discovering such a large assemblage suggests the animals may have travelled in herds - like modern-day kangaroos, said palaeontologist Karen Black, who led the research team.

The specimens offer an extra insight into the life of an extinct creature

But how the animals all ended up in the cave remains a mystery. One theory is that they accidentally plunged into it through an opening obscured by vegetation and either died from the fall, or became trapped and later perished.

The Nimbadon skulls include those of babies still in their mothers' pouches, allowing the researchers to study how the animals developed.

The skulls reveal that bones at the front of the face developed quite quickly, which would have allowed the baby to suckle from its mother at an extremely young age.

Those findings suggest that Nimbadon newborns developed very similarly to modern kangaroos - likely being born after a month's gestation and crawling into their mother's pouch for the rest of their development, Black said.

Nimbadon also may have something in common with another marsupial. The fossils revealed the creatures had large claws, which may have been used to climb trees - as koalas do, Dr Black explained.

"To find a complete specimen like that and so many from an age range is quite unique," said Dr Liz Reed of Flinders University in South Australia, who was not affiliated with the study.

"It allows us to say something about behaviour and growth and a whole bunch of things that we wouldn't normally be able to do."