Gaia celestial mapper heads out of UK

- Published

From the UK, Gaia goes to France and its final preparations before the launch campaign

It should be one of the great space ventures of the decade.

The Gaia satellite will be sent far from Earth to map the positions of more than a billion stars in our galaxy.

Remarkable sensitivity should also enable the observatory to see hundreds of thousands of new celestial objects, including previously unknown planets.

The main structure of the spacecraft was moved this week from the UK factory where it has been for a year to undergo tests on its propulsion system.

EADS Astrium in Stevenage transported Gaia by road to Ampac-ISP at Aylesbury for checks on its cold gas micro-thrusters. Once this work is complete, the structure will then go to Astrium's Toulouse, France, facility for final preparations.

The European Space Agency (Esa) satellite is due for launch in 2012 on a Soyuz rocket from the new Sinnamary spaceport in French Guiana.

Gaia is a successor to Europe's Hipparcos space astrometry mission which ran in the late 1980s and early 1990s. It catalogued more than 100,000 stars in our galaxy.

Although a billion stars sounds a lot, it is perhaps just 1% of all the stars in our galaxy

The new mission is a step change in capability, however. Its billion-pixel camera system will give scientists an unprecedented 3D map of the sky.

Over a five-year period, it will chart the precise positions, distances, movements, luminosities, and changes in brightness of stars. These details will unlock new information about the structure, origin and evolution of our Milky Way Galaxy.

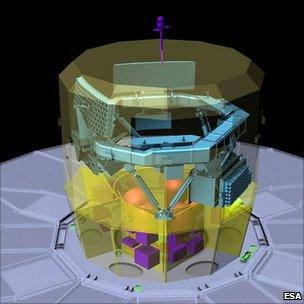

The payload module (blue) will eventually sit atop the service module (yellow)

And because Gaia will track anything that passes across its field of vision, it is likely also to see countless objects that had hitherto gone unrecorded - such as asteroids, planets beyond our Solar System, and tepid stars that never quite fired into life.

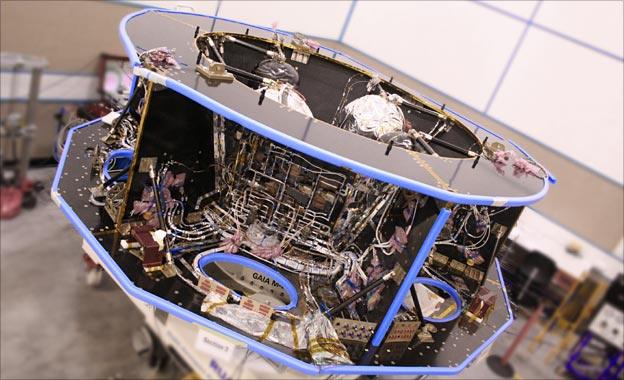

What you see in the image at the top of this page is Gaia's electrical and service module.

This is the part of the satellite that will do all of the "housekeeping" in space. It contains elements such as the attitude and orbit control system, the avionics, the computer and data handling subsystems. A large antenna will go underneath the structure to allow Gaia to talk to Earth.

What you do not see here is the payload module that will eventually go on top. This will be the unit that contains Gaia's telescopes and camera system.

Nor do you see the thermal shield which will open - petal-like - from the underside of the service module to give protection to Gaia's sensitive optics.

"Gaia came to Stevenage about a year ago as a bare structure," said the Astrium UK Gaia project manager, Andy Whitehouse.

"Since then we've integrated the propulsion system. We've built all of that offline and then put it on the structure. There's a lot of pipework that runs around inside, and the tanks are also inside as well."

Mark Tomlin, the assembly and integration test manager, added: "There wasn't much time to bring all this together. We've done almost 500 welds on the mechanical service module and that's taken us on the order of six months to achieve. It's been a monumental task. Each weld has to be X-rayed and cleaned."

A major task for the UK is in preparing Gaia's electronics and data processing units

As a lead member state of the European Space Agency, the UK is playing a prominent role on the mission, both scientifically and industrially.

The immense array of camera detectors, or CCDs (charge-coupled devices), is being provided by e2v at Chelmsford.

"The bulk of the work going on here at Astrium UK is on the electrical side, not the mechanical side," observed Dr Ralph Cordey, the company's head of science.

"This includes the crucial onboard processing units, which turn the prodigious amounts of data Gaia will get from its CCDs into a data stream that can be sent to Earth."