Stars reveal carbon 'spaceballs'

- Published

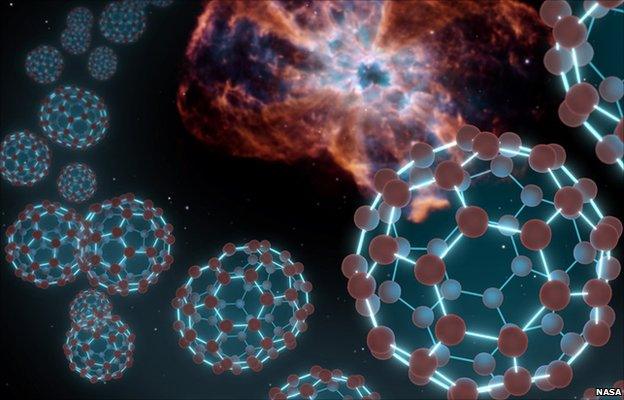

The football-shaped molecules are the largest molecules ever found in space

Scientists have detected the largest molecules ever seen in space, in a cloud of cosmic dust surrounding a distant star.

The football-shaped carbon molecules are known as buckyballs, and were only discovered on Earth 25 years ago when they were made in a laboratory.

These molecules are the "third type of carbon" - with the first two types being graphite and diamond.

The researchers report their findings in the journal Science.

Buckyballs consist of 60 carbon atoms arranged in a sphere. The atoms are linked together in alternating patterns of hexagons and pentagons that, on the molecular scale, look exactly like a football.

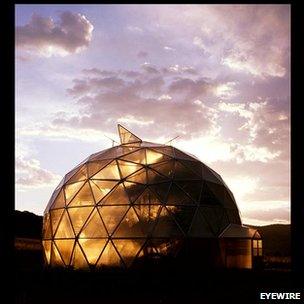

They belong to a class of molecules called buckminsterfullerenes - named after the architect Richard Buckminster Fuller, who developed the geodesic dome design that they so closely resemble.

The research group, led by Jan Cami from the University of Western Ontario in Canada, made its discovery using Nasa's Spitzer infrared telescope.

Professor Cami and his colleagues were not specifically looking for buckyballs, but spotted their unmistakable infrared "signature".

"They oscillate and vibrate in lots of different ways, and in doing so they interact with infrared light at very specific wavelengths," explained Professor Cami.

When the telescope detected emissions at those wavelengths, Professor Cami knew he was looking a signal from the largest molecules ever found in space.

"Some of my undergraduate students call me a world record holder," he told BBC News. "But I don't think there's a record for that."

The molecules were named after the developer of the geodesic dome

The signal came from a star in the southern hemisphere constellation of Ara, 6,500 light-years away.

Professor Cami said the discovery was perhaps not surprising, but was "very exciting".

"Lots of scientists have expected that they would exist in space, because they are amongst the most stable and durable of materials," he said.

"So once they've formed in space, would be very hard to destroy them.

"But this is clear evidence of an entirely new class of molecule existing there."

The researchers now want to find out what fraction of the Universe's carbon might be "locked up" in these spheres.

They also want to use the known properties of buckyballs to gain a better understanding of physical and chemical processes in space.

The discovery may even help shed light on other unexplained chemical signatures that have already been detected in cosmic dust.

Third way

Back on Earth, the discovery of buckyballs' existence was also accidental. Researchers were attempting to simulate conditions in the atmospheres of ageing, carbon-rich giant stars, in which chains of carbon had been detected.

"The experiments were set up to make those long carbon chains, and then something unexpected came out - these soccer ball type molecules, which just looked weird," said Professor Cami.

"And now it turns out that those conditions that were deliberately created in a laboratory actually occur in space too - we just had to look in the right place."

Sir Harry Kroto, now at Florida State University in the US, shared the 1996 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the discovery of buckyballs.

He commented: "This most exciting breakthrough provides convincing evidence that the buckyball has, as I long suspected, existed since time immemorial in the dark recesses of our galaxy.

"It's so beautiful that it's been hiding from us and it took an experiment trying to uncover what was going on in stars to find it."

He told BBC News: "All the carbon in your body came from star dust, so at one time some that carbon may have been in the form of buckyballs."