Gulf oil leak: Biggest ever, but how bad?

- Published

The oil has covered waters key to creatures such as crabs

So now we know.

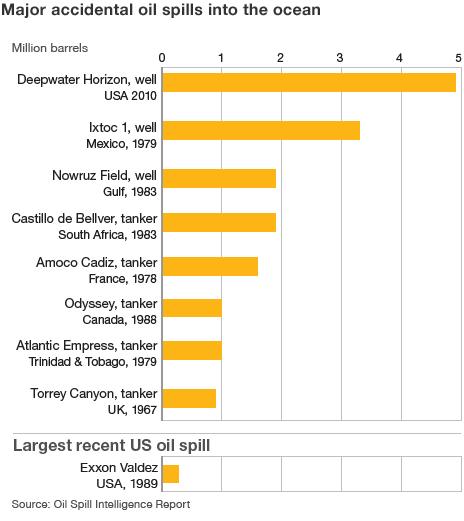

Following release of the US government's latest estimate, the Deepwater Horizon disaster is confirmed as the biggest ever accidental release of oil into the oceans.

It exceeds the 1979 Ixtoc I leak - also in the Gulf of Mexico. It's comfortably bigger than tanker releases such as the Torrey Canyon and Amoco Cadiz, and 20 times the size of the 1989 Exxon Valdez spill with which it is often compared.

Now that BP finally appears to have the flow under control, an important question - perhaps the most important of all - is being asked: it may have been the biggest, but was it the worst?

It is a simple-sounding question, but devilishly hard to answer.

What impacts are we talking about - on the coast, on the ocean surface, or the sea floor?

Which species are we including - fish, shrimp, insects, plants, birds, whales, turtles - or some combination of them all?

Are we looking long-term or short-term, local or regional - and are we to include or exclude impacts from the use of chemical dispersants and fires and the other containment measures?

One thing that is clear is that different parts of the Gulf coast have seen very different levels of impact.

Grasses in the wetland regions show damage - but they may recover

Two weeks ago, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (Noaa) announced that so little oil was being seen in a zone covering more than 26,000 square miles (67,000 sq km) - a quarter of US territorial waters in the Gulf - that fishing could safely re-start.

Yet in other areas, particularly along the coast, people are struggling daily to nurse oil-soaked birds back to health.

Many commentators were saying during the early days of the episode that the ecological impacts would depend largely on the vagaries of winds and tides; and so it has proven.

Noaa has said that about three-quarters of the 4.9 million barrels leaked into the Gulf waters has already vanished from the area - through evaporation, capture, burning, or dispersion.

But that still leaves more than a million barrels at sea.

As a formerly significant US figure said in the context of a different Gulf: there are known unknowns, and unknown unknowns.

Danger zone

Andy Nyman, an associate professor of Wetland Wildlife Ecology at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge, has spent years conducting laboratory and field research into the possible impacts of oil spills on the coastal wetlands that are so vital as nurseries for fish and shrimp, nesting grounds for birds and as coastal defences.

"It's going to be difficult to pick up the impacts of the oil spill and separate those from natural seasonal variability," he says.

"Impacts we'll be looking for in the short term include the loss of wetland grasses and reductions in fish and other things that live in the water.

"In the longer term we could see reduced productivity in these populations, but we may not be able to detect it because the annual variations are quite large."

He relates taking two trips along the coastal fringe in recent weeks.

In one zone, they could see virtually no impact on the grasses. In the other, a stretch of coast about 10km (six miles) long showed significant damage, with swathes of grass brown and shedding leaves.

Yet on many plants, new green stems were sprouting - just as happened on the grasses in Professor Nyman's experimental plot after he had coated them in oil to see how they would perform.

How the grasslands will fare in the long term is definitely a known unknown.

Time's lens will also reveal the impact on fish and shrimp, so vital to the local economy.

But again, the stock varies naturally from season to season; so picking out a specific impact of the oil leak could prove difficult.

Out in the Gulf itself, the impact on bluefin tuna is potentially significant. The spawning grounds have been covered in oil at times, and there are fears that an entire year's brood may be missing.

But that will not become clear for several years. Estimating the marine impacts will also be complicated by the fact that closing the fisheries has given stocks a respite from nets and hooks.

Deep unknowns

So how much do we know?

Several hundred thousand seabirds died from the Exxon Valdez spill - possibly as many as 600,000, according to some estimates.

By contrast, the number of birds found dead along the Gulf of Mexico coast is a little over 3,000.

Just over 500 sea turtles and 64 dolphins have also been found dead.

But that is partly a function of the leak's geography; turtles would not have been affected by the Exxon Valdez simply because they do not frequent the coasts of Alaska.

Conversely, the Exxon Valdez claimed the lives of several thousand sea otters - which do not live along the Gulf coast.

Turtles are among the animals affected by the leak

An important unknown - about which very little is known - is the importance of flows of oil deep underwater that were detected a couple of months ago and that almost certainly have dispersants mixed in.

The use of these chemicals is controversial. They keep the oil away from shore - but the cost is paid in clogged wads of crude that sink to the sea floor.

Paul Anastas, assistant administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency's (EPA) Office of Research and Development, acknowleged that dispersants were far from perfect, but said their use here had been, on balance, positive.

"The purpose of the dispersants is to put the oil in a form that can be broken down and degraded by natural microbes," he said.

"Once it makes to it to shore it is causing an impact on our most sensitve ecosystem that is extremely difficult to clean up and has an extreme negative impact on the ecosystem of the Gulf."

The EPA has just finished a batch of tests showing that dispersants mixed with oil are no more toxic to marine life in the Gulf than oil on its own - contradicting the claims of some critics.

The Deepwater Horizon operation saw the injection of 771,272 gallons (2,919,582 litres) of dispersant at depth, in addition to the 1,072,514 gallons (4,059,907 litres) used on the surface.

The impact of the deep water deployment is definitely an unknown unknown, as it has not been used on anything like this scale before.

Expeditions are planned to investigate the impact on reefs, but they have yet to report.

Other important investigations are going on into how quickly the oil is breaking down in the warm Gulf waters - something that should in principle happen much faster than in the icy conditions of Alaska's Prince Edward Sound, or the Cornish seas where the Torrey Canyon spilt its cargo in March 1967.

That rate will have practical implications for the seabirds that will come to winter along the Gulf coasts - the piping plover, the blue-winged teal and the northern pintail - because it will largely determine how much oil will be there to greet them.

Two decades on, the ecological impacts of Exxon Valdez are still being counted.

And while the warmer Gulf waters are unlikely to take quite so long to settle, even a preliminary reckoning will have to wait until the first wintering birds have returned, shrimping boats have cast their nets again right across their grounds, and the wetland grasses have had a first chance to shed their oily carapaces and sprout anew in a fresh Spring.

- Published21 July 2010