Parasite pioneer's worm naming reward

- Published

A UK scientist who has spent years involved in pioneering work to understand how a highly virulent parasite infects people in Tibet and western China has been rewarded - by having a microscopic worm that lives in voles' guts named after him.

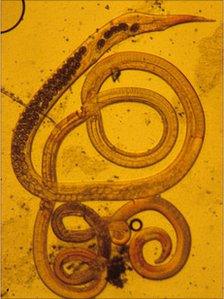

Having a worm named after him was a reward for Professor Craig's work

"We were collaborating with several groups, including a French group, specifically to identify those rodents that might act as a reservoir for this nasty parasite," explained Phil Craig, a professor of biology at the University of Salford.

"While doing this, a number of other organisms were found, including the one that was named Heligmosomoides craigi," he modestly recalled.

The worm is only found in the gut of a particular species of vole in the Microtus genus, which is endemic to parts of China and Mongolia.

The honour was bestowed upon him by French researchers earlier this year in recognition of devoting his "professional life to promoting parasite eco-epideiological studies in China".

For more than a decade, Professor Craig has been working in Tibet and western China to study the highly pathogenic parasite that is transmitted from dogs and foxes to people.

He insisted that the issue of zoonoses (diseases transmitted from animals to humans) on the Tibetan Plateau was the more interesting story, rather than how a niche species of roundworm got its name.

"What happens is that a Tibetan fox predates on a rodent, and the parasite is transmitted to the fox," he began.

"Now, if a dog eats a rodent infected with this particular parasite, then the dog can become infected and has the worm in its gut and can pass out infected eggs. That means people can become infected as a result of contact with the dogs or dog faeces."

'Hard to treat'

During field studies, Professor Craig and fellow researchers found that there was a higher than expected prevalence of cestodes (tapeworms) belonging to the genus Echinococcus, all of which are zoonotic and cause a disease called echinococcosis in humans.

"It is potentially a lethal disease," he warned. "Without treatment, about 95% of the people affected would die within 10 years of diagnosis.

"If someone gets infected with this parasite, they will not know for about 10-15 years.

"By that time, it is likely to be very advanced. Although it is a parasite, it starts destroying the liver with a big lesion and it is very hard to treat."

For some areas, where poor rural communities farm uplands a few hundred kilometres from the Plateau, he suggested that the expansion of agriculture in recent decades could have contributed to the high rates of infection.

"People have terraced hillsides and deforested areas for marginal agriculture. When you deforest an area and do not use it for agriculture then you get secondary scrub developing.

"This scrub - with shrubs, bushes and, to some extent, grasslands - is quite a good habitat for a number of vole species which we think are really excellent hosts for the parasite.

"That in itself may not be a problem, but people keep dogs... and dogs predate these rodents."

Double whammy

However, when the team began to hear about cases on the Tibetan Plateau, they knew that deforestation could not be a contributing factor.

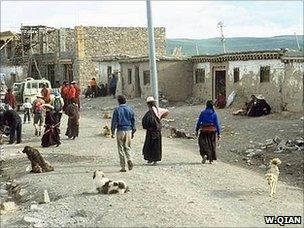

Dogs are a possible bridge for the parasites to infect humans

"Deforestation does not apply in Tibet because there are no trees above about 3,800 metres," Professor Craig explained.

"So we looked at this and asked why was there so much of the this rare, but nasty, disease around when there is apparently a homogenous grassland landscape?

"It turns out that it is not quite as homogenous as we think, and there might be a bit of anthropogenic influence [because] Tibet is under a bit of pressure - either voluntarily or through provincial governments - to put in fencing to protect pastures from overgrazing."

As a result of the fencing, the team observed two results:

"Firstly, you protect the pasture inside the fenced area," he said, "while outside these fenced areas tend to see an increase in overgrazing because it is common pasture.

"It seems from our studies, interestingly, that you get one set of voles that like the long grass, particularly within the fenced areas, and you get another set of small mammals that like the overgrazed landscape.

"Both sets of these animals are good hosts for this pathogen. We certainly find that the risk of human disease is greater in Tibetan communities with fencing than areas that remain unfenced."

Screening carried out by the team, using portable ultrasound equipment, revealed that about 15% of people were infected in some communities.

But Professor Craig added: "If you take certain proportions of Tibetans, such as herdsmen and pastoralist, then you find the figure is much higher - up to 20%."

'No vaccine'

The link between the parasite's natural reservoir and humans has been identified as dogs, which play an important role for families in these communities.

Dogs are part and parcel of Tibetan settlements

"Almost every Tibetan family in the areas of our studies would have at least one dog, perhaps up to five," the University of Salford researcher explained.

He added that the animals were effectively guard dogs to protect livestock from wolves and also to protect their houses/tents from unwanted visitors.

"So the dog is often tied up during the day outside the house or tent, and at night they are released when they go out and forage; this is when they do quite a bit of predation."

The team have been working in partnership with China's health ministry.

"We usually go in with three different teams," Professor Craig explained.

"One is a medical team, which would screen the local population, who volunteer to be screened. That team would also have physicians, so if a case was identified, that person would be offered treatment immediately.

"There is one particular drug which can have a useful effect - it might not cure, but it certainly will prevent the parasite doing more damage in the liver, but this has to be taken quite regularly.

"Another treatment is the surgical removal of the lesions via quite a serious operation."

The second team is known as the "dog team", which includes vets who take faecal samples from dogs, allowing the researcher to detect whether the dog is infected.

"There are some quite good de-wormers that can kill the parasites - but it is not a vaccine, if that dog then eats an infected rodent a few days later then it is going to become reinfected."

A few years ago, Chinese authorities began a control programme that involved establishing a regular "dog dosing regime" to limit the opportunities for the parasite to spread.

The final team is an "ecology team", made of ecologists and geographers who build up a picture of what is going on in the human settlements and within the wider landscape.

The work, Professor Craig explained, has led to the team identifying "hotspots", which have been prioritised in the national control programme.

While the team's research focuses on Tibet and China, the findings can be applied to other parts of the globe.

"It does have a wider relevance because of the red fox transmission that is occurring in Europe," he said.

"It is spreading in Europe because red fox numbers have risen dramatically; probably two reasons: rabies control has been very effective, and rabies used to kill about 20% of foxes in Europe.

"Secondly, they have become urbanised - as they have in the UK - and that is resulting in an increase in their numbers."

He said the prevalence of the parasite among local populations of red foxes in countries such as Poland, Belgium, Netherlands and western France - where it was once considered to be very low - was now on the increase. To date, the parasite has not been found in UK wildlife.

"But the rates within humans of this disease and other echinococcoses in Europe are very, very low compared to what we see in Tibetan communities."