Fossils may be 'earliest animals'

- Published

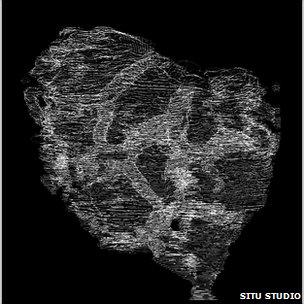

Digital imagery reveals a network of internal tunnels in the fossils

Tiny, irregularly shaped fossils from South Australia could be the oldest remains of simple animal life found to date.

The collection of circles, anvils, wishbones and rings discovered in the Flinders Ranges are most probably sponges, a Princeton team claims.

The rocks in which the forms were found are 640-650 million years old.

This is at least 70 million years older than some other claims for the most ancient animals in the fossil record.

The research, led by Professor Adam Maloof, is published in the journal Nature Geoscience.

"People have certainly proposed complex organisms, like eukaryotic algae or protists, and have even proposed animals in the form of trace fossils (preserved tracks) prior to the sponges that we report," he said.

"But I think we could confidently say that our sponges are the first somewhat convincing body fossils of an animal before the Ediacaran Period."

The Ediacaran, which came at the end of the last great global glaciation, produced indisputable evidence for animal life - slug-like organisms called Kimberalla, whose remains are found today in 555-million-year-old sediments in Australia and Russia.

But whilst these shapes are recognisably animal, the Flinders objects have been described as such only after lengthy analysis.

The Princeton team found them by accident whilst studying rocks the group thought might hold clues about environmental conditions just before the very severe ice age.

"We were accustomed to finding rocks with embedded mud chips, and at first this is what we thought we were seeing," Professor Maloof recalled.

"But then we noticed these repeated shapes that we were finding everywhere - wishbones, rings, perforated slabs and anvils. By the second year, we realised we had stumbled upon some sort of organism, and we decided to analyse the fossils.

"No-one was expecting that we would find animals that lived before the ice age, and since animals probably did not evolve twice, we are suddenly confronted with the question of how some relative of these reef-dwelling animals survived the 'snowball Earth'."

The fossils are visible in the Flinders rock as red shapes

The team could not remove the fossils from the surrounding limestone because they were completely embedded and made of the same material (calcite). Instead, the group cut thin sections and digitally reconstructed the forms to assess their internal structure.

"We took fossils home; we sliced and diced them up, imaging every 50 microns or so and generating 3D images of these fossils which were otherwise inaccessible to traditional techniques," Professor Maloof told reporters.

"The result is an object about a centimetre in size that most closely resembles sponges, which are animals."

Key to this interpretation is the presence in the organisms of small channels about a millimetre in diameter. Modern sponges display similar structures. As simple filter-feeders, sponges use these canals to extract food as seawater flows through the them.

The oldest known, generally accepted fossilised sponges prior to the Flinders claim are about 520 million years old.

Not everyone is ready to accept the Princeton assessment yet, however.

Dr Jim Gehling, a Senior Research Scientist from the South Australian Museum, said he saw no convincing evidence to support the interpretation that the "coco-pop breakfast-cereal-like forms" were ancient sponges.

The fossils were found in the West Central Flinders Ranges

"They may just as easily be mineralised bacterial cells or some other sort to single-celled microbes," he argued.

And he added: "Sponges should have first appeared in the Cryogenian Period about 650 million years ago - judging by times of branching in family trees in the animal kingdom, based on molecular clocks and the discovery of sponge biomarkers (steranes) preserved in rocks of this age.

"The problem is that we have no idea what the very earliest sponges may have looked like. This means that the discovery of any weird shape in rocks of this age may lead to claims of the 'oldest sponge-grade fossils'."