Computer blow to Europe's Goce gravity satellite

- Published

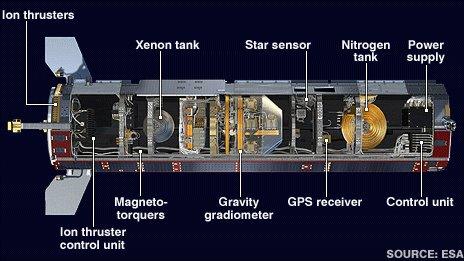

Goce flies lower than any other scientific satellite

A flagship European Earth observation satellite has been struck by a second computer glitch and cannot send its scientific data down to the ground.

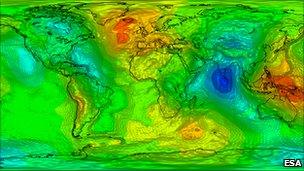

The Goce spacecraft is on a mission to make the most precise maps yet of how gravity varies across the globe.

In February, a processor fault forced operators to switch the satellite over to its back-up computer system.

This too has now developed a problem and engineers are toiling to make the spacecraft fully functional again.

The European Space Agency (Esa) remains confident the situation can be recovered, however.

"There's no doubt about it: we're in a difficult situation, but we are not without ideas," Goce mission manager Dr Rune Floberghagen told BBC News.

Only last year, Esa lost the use of an instrument on its billion-euro Herschel space telescope but still managed to find a way to bring it back online even though engineers were separated from the malfunctioning hardware by more than a million kilometres of space.

All the other systems on Goce continue to work normally, including the state-of-the-art gradiometer that senses the subtle differences in the pull of gravity from place to place on the Earth's surface.

The instrument's data-gathering has now been suspended and the spacecraft pushed higher into the sky while the latest anomaly is investigated.

Goce first ran into difficulties in February when it experienced an extremely rare chip failure in its primary, or A side, computer. The spacecraft was therefore switched across to its redundant, or B unit, while engineers sought to understand the problem.

Then on 18 July, the second computer was hit by separate issue. This anomaly affects a communication link between the processor board in the B computer and a module that prepares telemetry for transmission to the ground. As a consequence, software-generated telemetry cannot get to Earth.

The B computer has been re-booted but the error in the link persists.

The positive news is that the Goce operations team is making headway in getting some functionality back on the primary computer. The hope is that it can be made stable enough to handle telemetry tasks while the B unit is given the responsibility for processing.

"If we have just two half-computers, we can stitch them together and get Goce working again," said Dr Floberghagen.

The mission has been a remarkable venture to date. The satellite is the lowest-flying scientific spacecraft in operation today.

Its arrow shape, fins, and electric engine help keep it steady as it flies through the wisps of air still present at an altitude of 260km.

Even if it were to be lost now, Goce has collected some two-thirds of the gravity data originally expected from the mission at launch in March last year.

Some two-thirds of the gravity data originally expected from the mission have been acquired

This data will have many applications, especially in the area of climate studies by bringing new insights into how gravity influences the way ocean waters move and so redistribute heat around the planet.

In June, just before the latest anomaly set in, the Goce science team published its first geoid - a specialised map that traces "the level" on Earth.

Because gravity determines which way is "up" and which way is "down", the geoid makes it possible to compare two arbitrary points on the globe to determine which one is "higher" - critical information for anyone who might want to construct a pipeline across several countries that do not share a common height system, for example.

A senior investigation board at Esa is looking into the root causes of the computer failures, to understand the implications for other satellite missions.

"It's frustrating when you consider all the focus and effort that went into the building of the innovative parts of Goce, like its gradiometer - to see all that work perfectly, and then be faced with failures in elements that are really 'bread and butter' in any satellite mission," Dr Floberghagen observed.

The current recovery strategy is expected to take until at least the middle of September.