AMS particle detector lands at Kennedy Space Center

- Published

The Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer was loaded on to the Galaxy transporter at Geneva airport

The most expensive science experiment devised for the International Space Station (ISS) has arrived in Florida to make it ready for launch.

The Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer (AMS) will be attached to the outside of the orbiting platform to conduct a survey of cosmic rays.

Scientists hope the research will reveal new insights into the origin of the Universe and what it is made of.

The $1.5bn machine will be taken up to the ISS by space shuttle Endeavour.

The launch is currently scheduled for 26 February and could mark the final flight for the US space agency's re-usable spaceplane system.

AMS was delivered to the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in a US Air Force C5 Galaxy transporter plane from Europe.

The 7-tonne machine will be housed in a cleanroom over the coming months for some final tests before being packed into Endeavour's payload bay and rolled out to the launch pad.

The AMS project is the collaborative effort of 16 nations sponsored largely by the US Department of Energy.

Much of the technology in the experiment has been developed and built at Cern (European Organisation for Nuclear Research) near Geneva, Switzerland - the same facility that hosts the world's biggest particle physics experiment, the Large Hadron Collider.

AMS will be doing very complementary science.

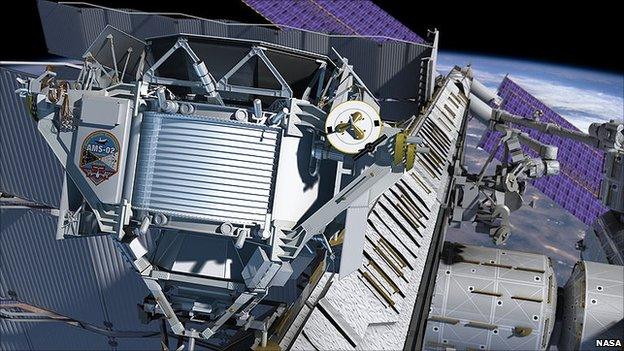

The device will be mounted on the station's truss, or backbone.

AMS will ride to space in the back of the Endeavour orbiter in February

Over the course of several years, it will count and characterise high-energy cosmic rays - fast-moving subatomic particles and nuclei that originate in deep space and which continually rain down on Earth.

Because the planet's atmosphere tends to filter out much of this torrent, an orbiting detection system is seen as the best way to get at the real statistics of these particles.

AMS will identify them by their charge, mass and energy, in order to determine their origin.

It will seek definitive data on whether the Universe retains any large quantities of anti-matter - matter with an alternate electrical charge to normal matter and which theorists suspect was created in equal amounts in the Big Bang but then destroyed.

The experiment also hopes to detect evidence for dark matter which scientists say makes up some 25% of the Universe but which is invisible to conventional telescopes.

In addition, AMS should provide valuable new information on astrophysical phenomena such as black holes and exploding stars - the high-energy locations thought to produce substantial numbers of cosmic rays.

Nobel Laureate and AMS project leader, Professor Sam Ting, travelled with the detector to America.

He told BBC News: "Over the past 50 years there has been enormous progress in understanding astrophysics and cosmology, but all these measurements have been in using light rays.

"In space, beside light rays, there are an enormous amount of charged particles - positrons, electrons, protons, deuterons, anti-deuterons and so forth. These have hardly been measured," he said.

"We want to study the physics of charged cosmic rays. No-one has put a detector with such a sensitivity - using the technology developed at Cern/LHC - in space before."

AMS was originally envisaged to cost just a few hundred million dollars, but the project has been subjected to a series of delays - some technical but mostly political.

At one stage, it looked as though the experiment would not even get to the ISS when Nasa announced the curtailment of the shuttle programme following the Columbia accident in 2003.

Additional funds provided by the US Congress and a reshuffling of the shuttle manifest eventually found AMS a ride to orbit.

AMS passes in front of Kennedy's vast Vehicle Assembly Building

Simonetta Di Pippo, the director of human spaceflight at the European Space Agency, was at Kennedy to greet AMS when it landed. She said the recent decision to extend the life of the ISS was good news for science.

"With the space station now staying in orbit for a minimum additional minimum 10 years, AMS will be able to achieve so much more," she told BBC News.

"We are trying to enlarge more and more the number of fields in which we use the space station. We are working on climate change experiments from the ISS; we are working on using the ISS more for exploration purposes, and in fields like space weather, observing the Universe and the Earth. We're showing how the ISS can be useful for science and society."

The Endeavour flight - designated STS-134 - is supposed to be the last shuttle mission before Nasa's orbiter fleet is retired to museums. But there are strong efforts now under way in Congress to add at least one further mission next year.

The AMS will be positioned atop the starboard truss, or backbone, of the space station

- Published2 July 2010