'Rapid' 2010 melt for Arctic ice - but no record

- Published

The Arctic on 3rd September, as visualised using data from Nasa's Aqua satellite

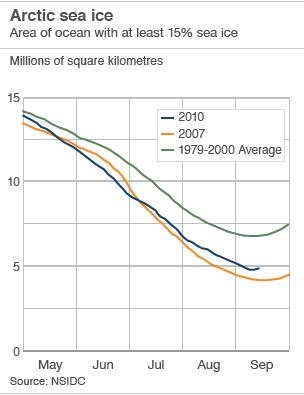

Ice floating on the Arctic Ocean melted unusually quickly this year, but did not shrink down to the record minimum area seen in 2007.

That is the preliminary finding of US scientists who say the summer minimum seems to have passed and the ice has entered its winter growth phase.

2010's summer Arctic ice minimum is the third smallest in the satellite era.

Researchers say projections of summer ice disappearing entirely within the next few years increasingly look wrong.

At its smallest extent, on 10 September, 4.76 million sq km (1.84 million sq miles) of Arctic Ocean was covered with ice - more than in 2007 and 2008, but less than in every other year since 1979.

Walt Meier, a researcher at the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) in Boulder, Colorado, where the data is collated, said ice had melted unusually fast.

"It was a short melt season - the period from the maximum to the minimum was shorter than we've had - but the ice was so thin that even so it melted away quickly," he told BBC News.

The last 12 months have been unusually warm globally - according to Nasa, the warmest in its 130-year record.

This is partly down to El Nino conditions in the Pacific Ocean, which have the effect of raising temperatures globally.

With those conditions changing into a cooler La Nina phase, Nasa says 2010 is "likely, but not certain" to be the warmest calendar year in its record.

Arctic ice is influenced by these global trends, but the size of the summer minimum also depends on local winds and currents.

This means ice can be concentrated in one region of the Arctic in one year, in another region the next.

This year, the relative absence of ice around Alaska has brought tens of thousands of Pacific walruses up onto land recently.

In terms of the longer-term picture, Dr Meier said the 2010 NSIDC figures tally with the idea of a gradual decline in summer Arctic ice cover.

But computer models projecting a disappearance very soon - 2013 was a date cited by one research group just a few years ago - seem to have been too extreme.

"The chances of a really early melt are increasingly unlikely as the years go by, and you'd need a couple of extreme years like 2007 in a row to reach that now," he said.

"But the 2040/2050 figure that's been quoted a lot - that's still on track. It could end up being wrong, of course, but the data we have don't disprove it."

NSIDC will release a full analysis of the 2010 data next month.

- Published15 September 2010

- Published9 July 2010

- Published12 June 2010