Inside UK forensic insects team

- Published

Immediately after death, a body emits chemicals which rapidly attract insects

At the top of a long staircase in a room in a tower, far away from the throng of visitors and other scientists and laboratories is the Natural History Museum's insectory.

And it's tucked away for a very good reason.

Inside, your senses are greeted by the smell of rotting dog food, the buzz of blowflies and the purple UV light of the fly killer ready to zap escapees.

This is where the museum's forensic entomologists breed different species of fly in a bid to help the police solve crimes.

Museum scientist Amoret Whitaker is one of just three forensic entomologists in the UK who regularly works with the police to determine the time of death of a corpse.

"As soon as a person dies, their body starts to decompose and they give off specific odours. These different chemical signals are very very attractive to insects. And in the inital stages it's especially blowflies."

Amoret Whitaker gives a tour of the 'insectory' at the Natural History Museum

"So when someone dies, fairly soon, it could be within minutes blowflies are attracted to the body and they will start laying eggs immediately. These will hatch into larvae or maggots and the developmental cycle will continue."

"You get a lot of male blowflies hanging around, sitting on plants around the body, waiting for suitable female mates."

And it is this cycle of life and death that is critical in helping the police when they are uncertain of the timing of someone's death.

Critical timing

By understanding the "succession" rates or the speed of growth of flies, from an egg to the larval then adult stage she and her colleagues can determine the likely time that person died.

But scientists only have developmental data on perhaps half of the twelve or so species of fly that are regulary found on dead bodies.

By breeding them in "captivity" under different temperature conditions they can get more accurate information about the timing of their growth and so the process of death.

Forensic entomology can help determine to within hours the time someone died.

The accuracy of that timing depends partly on how long the body has been decomposing. If she can get to see a corpse within days of its death, when that person died can be worked out to an accuracy within hours.

But, if the body has lain undiscovered for weeks, or even months, then the precision of timing can be narrowed to a matter of days.

This timing can even be used to help determine whether a suspicious death should be treated as murder.

"In some cases of assault, if someone has been seen leaving a pub after a fight say, then that person is found dead a few days later, if we can determine when they died to a matter of hours, we can help establish whether the person died from the assault or other causes."

The time of year can dramatically affect how a body decomposes. In one case Amoret and colleagues were involved in, a man disappeared in November but his body was not discovered until the following February.

One pathologist report suggested the body had been dead for just a few weeks. In fact because he had died in winter his body had effectively been "mummified".

Forensic Entomologist Amoret Whitaker explains how she preserves flies and maggots

The critical evidence came from Calliphora vicina, a bluebottle blowfly often found on dead bodies. C vicina grows all year round but in winter its development slows right down. While it remains alive, it becomes inactive at temperatures below 1C.

This peculiarly slow rate of development meant Amoret and colleagues could prove the man had died months ago rather than weeks.

The man had left a pub, taken a short-cut home then slipped and broken his neck.

The police regularly use Amoret and her colleagues' expertise.

"We can go two months with nothing but then be asked to help with six cases in a couple of weeks."

"It's rare that our evidence is used in court. It's more common that we give police a time window and they can then gather further evidence."

Forensic entomology can even be used in cases of burnt bodies, as insects may still be found, feeding within the body cavities. If a cadaver has been burnt this makes estimating time of death difficult for the pathologist.

Between working with police in the UK and research at the Natural History Museum, Amoret also works at the anthropology department at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville.

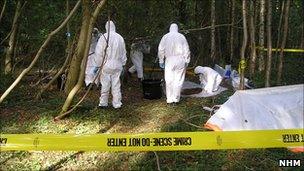

Pigs are used as a model for how human corpses decompose

There she compares the decomposition of dead pigs and human cadavers. Some people have nicknamed this place the "body farm".

In the summers of 2008 and 2009 she compared the decomposition of three pigs and three human cadavers.

Her research isn't finalised but initial results are positive, confirming that pigs are a good model for how a human corpse decays.

"The same species of insects are attracted during the same time periods to both types of cadaver. Large numbers of blowflies from days 1-5, fewer on days 6-7, and a large drop from day eight onwards," she told BBC News.

She also says this research will be very useful for all cases where insect evidence is used.

"This work will have a big impact when it's published, for forensic entomologists all over the world. As it will show that pigs are a good model for humans, and therefore all the data gathered using pig cadavers can be applied to cases involving human cadavers."

Amoret Whitaker is just one of the scientists demonstrating their research at the one night only event "After Hours: Science Uncovered" , externalat the Natural History Museum on Friday 24th September between 1600 and 2200