Iceland's volcanic eruption yields ash clues

- Published

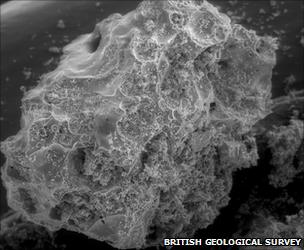

Microscopic images of ash were captured on tape

Samples collected using double-sided sticky tape could give fresh insight into the Eyjafjallajoekull eruption.

The samples could reveal how fine ash thrown up into the atmosphere by the Icelandic eruption fell to ground as clumps or "aggregates" of ash.

The British Geological Survey, external work will be used to create better models of how volcanic ash disperses after eruptions.

The eruption of the volcano in March this year caused chaos, shutting down huge swathes of European air space.

Long fingers

Dr Susan Loughlin, head of volcanology at the British Geological Survey, said the samples of ash retrieved from UK soil in the aftermath of the eruption came in a vast array of shapes and sizes.

"They're really quite beautiful. Some of the aggregates are dendritic, so they're really angular and have long fingers of... material.

"Others are quite round, quite blocky, quite densely packed," she told BBC News.

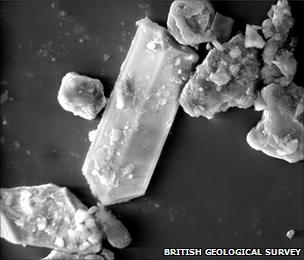

"And then we've also got really tiny crystals, which are very very beautiful under a microscopic view but extremely tiny."

Some of the individual grains of ash retrieved are less than one micron (a millionth of a metre) in diameter, while some of the clumps of ash are as large as 200 microns, about twice the width of a human hair.

The samples were collected on double-sided sticky tape as this method best preserves the structure of the fallen ash.

Fine analysis

The UK samples will be compared with those recovered in Iceland to build up a picture of how ash from the plume formed into these aggregates and fell to ground.

In Iceland itself, the process is thought to have been aided by electricity and water from the volcano's ice cap.

The particles come in the form of crystal and glass

"Near to the volcano, there's so much static in the plume with so much lightning going on, and that's causing the finer particles to stick together and fall out near the volcano," said Dr Loughlin.

"But also the plume was quite wet, and the films of water around these particles of ash are also causing them to stick together and they get larger and heavier and so they fall out."

This process of aggregation of the ash continued as the plume journeyed to Britain over the course of some 12 hours.

Understanding how quickly it occurred and how much fine ash remained in the sky will prove vital, she said. Data will go to the UK Met Office and be used to refine models of ash dispersal.

"What we want to know is how much ash is left up in the plume because that's what the civil aviation authorities are interested in.

"What we need to understand is how that plume evolves through time and how that fine ash is removed from the air."