Rich nations 'failing to deliver climate cash'

- Published

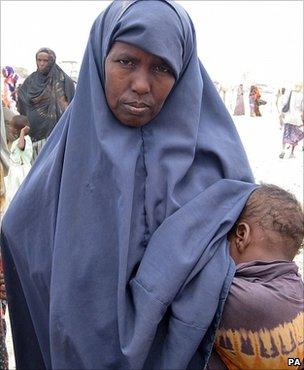

Campaigners say the money is essential to help people adapt to a changing climate

Rich nations are failing to live up to their promise of giving US$30bn to poor countries to help them cope with climate change, according to a report.

The money was pledged at last year's Copenhagen summit in order to build trust between rich and poor nations.

The scheme - championed by former UK PM Gordon Brown - is supposed to deliver the funds by the end of 2012.

But a report to the German government says much of the money has been taken from other aid budgets.

If the findings are correct, it confirms allegations by pressure groups that rich countries are repackaging existing funds and presenting them as special climate finance.

Campaigners claim programmes to tackle poverty will suffer if this is allowed to happen.

Cash transfer from rich to poor is a major theme at the Tianjin climate conference, the last major gathering before this year's UN climate summit in Mexico.

Delegates also heard an update about potential sources for the agreed $100bn long-term climate finance.

The report on the $30bn short-term cash, external is by the consultancy Climate Analytics. It says a total of $31.2bn has been pledged so far - more than the amount promised at the global gathering in the Danish capital last December.

Devil in detail

But the question is what counts as "new and additional finance". The term was used in the controversial Copenhagen Climate Accord, but has no agreed definition.

The paper concludes that if the only funds counted are new climate funds additional to official aid budgets since Copenhagen, then the sum raised so far is just $8.2bn.

The round of talks in China are the final ones before the UN climate summit in Mexico

A more generous definition of additional finance might see the allowable funds swelled to $17bn - but even this is far from the $30bn figure.

The report says there is very little transparency in rich countries' pledges.

The claim comes as rich nations are demanding transparency in developing nations' actions to tackle climate change.

"There must be much better verification of developed countries' finance proposals," Xie Zhenhua, China's chief climate negotiator, told BBC News.

Bill Hare from Climate Analytics said: "This is a really important issue because so much trust has been lost in the climate negotiations with so many rich nations failing to live up to their legally binding targets to cut emissions, then asking the developing nations to do more to tackle climate change.

"This fund will look like a scam if it's not improved. If you can't have trust - and this process has been severely damaged by lack of trust - it's going to be very bad news indeed."

John Drexage from the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) in Canada told BBC News: "We mustn't get too obsessed about this - if we are not careful a big chunk of the money will go in paying wealthy consultants from rich countries to find out how much money is new."

A former diplomat was more cynical about the "smoke and mirrors" of international finance: "Treasuries don't allow ministers to make spending pledges - they go into a side room and warn there is no new money available - then they get creative as to how to present a package that will look good on paper.

"There's a huge amount of grey area here - it's impossible to be precise on these figures."

Meanwhile, the meeting heard about progress from the high-level advisory panel tasked with finding the annual $100bn to be given by rich nations to poor nations from 2020.

This also formed part of the Copenhagen Accord from 2020, and the US$100bn was again first mooted by Gordon Brown, as a way to help poor countries cope with the projected consequences of climate change.

The panel's spokesman, Daniele Violetti, said the report would be finalised next week.

"The group is not proposing a 'silver bullet' for every problem - it's more a question of assessing what various revenues could generate over time," he said.

There could be eight sources of finance, most of them coming from the public sector.

It is reported that the panel has been considering bunker fuel taxes for aviation and shipping, but that a proposed Tobin tax (levy on currency traded across national borders) on financial transactions has been quashed by the US.

The panel's conclusions will be examined closely because the US and the UK both insist that public sector money will be used to leverage private sector investment - much of it from the carbon markets.

Henry Derwent, CEO of the International Emissions Trading Association, said governments might be over-estimating the cash that could be generated from markets.

"The current maximum primary market investment under the CDM (Clean Development Mechanism - the official international carbon trading market) is $2-3bn a year," he told BBC News.

"With the current trend in carbon prices, it doesn't seem to be going in the right direction to me - so it's hard to see how this could contribute a large proportion of $100bn."

The carbon market will burgeon if a comprehensive global deal on emissions is agreed - but observers in Tianjin are not optimistic that will happen in the next few years, if at all.

- Published7 October 2010