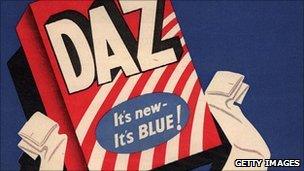

Biodiversity - a kind of washing powder?

- Published

Despite awareness of biodiversity increasing, some people still think it is a washing powder

When 2010 was named as the "year of biodiversity" by the UN, it began with a plea to save the world's ecosystems.

UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon said: "Biological diversity underpins ecosystem functioning... its continued loss, therefore, has major implications for current and future human well-being."

Radio 4's The World Tonight asked four experts what can be done to raise awareness of the issues surrounding biodiversity.

Kate Rawles, sustainability and environmental and ecological awareness lecturer at the University of Cumbria

Recently, members of the public were asked what biodiversity is. The most common answer was "some kind of washing powder".

Kate Rawles believes losing biodiversity is undermining our ability to meet basic needs

Modern societies are dangerously close to completely losing touch with the value of other living things and our place in natural systems.

If we are to arrest and reverse the rates of species extinction, the challenges are philosophical as much as they are political or economic and three major shifts in understanding are needed:

First, we need to tackle our sense of disconnection from the living world. We have lost sight of the fact that we are still earthbound animals living in ecosystems.

It is this disconnect that has allowed us to systematically degrade and destroy our own habitats without realising that just might be a problem for us.

Second, we need to understand our dependence on other forms of life. We like to think that we are the most important species on the planet but we need other species a lot more than they need us.

Losing biodiversity is not just about the tragic demise of the polar bear, it is undermining our ability to meet basic needs.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, other living things - from blue tits to basking sharks - are not just resources. We need other species but this is not the only reason why wiping them out matters.

This is to take an incredibly arrogant, and scientifically uninformed, view of life and its value - the ethical equivalent of thinking the sun revolves around the earth.

There is overwhelming evidence that having the chance to play outdoors in relatively natural surroundings as a child is the biggest factor in developing a concern for the environment as an adult. How we reconnect adults is more challenging.

Recognising the intrinsic value of other species in law so humans are put on a level playing field with other species would be a very good beginning.

Jonathan Porritt - founding director of Forum for the Future

It is a measure of the disconnect between humankind and the natural world that anyone could decide whether humans should be given priority over nature.

.jpg)

Jonathan Porritt believes that if we continue as we are going, then apocalypse truly looms

Without a fully-functioning, resilient natural world, we are nothing.

The principal reason we have put aside that natural wisdom is our obsession with economic growth. Growth drives everything and we simply ignore its mounting costs.

And the more of us human beings there are - 6.8bn today, 9bn predicted by 2050 - the higher those costs rise.

How much more incontrovertible scientific evidence do we need to understand that we have to change course now - not some distant point in the future - if we are to secure the foundations for our societies?

Here is the bottom line: if economic progress over the next two decades is based on the same war of attrition against nature that has characterised economic progress since the Industrial Revolution, then apocalypse truly looms.

And that means growth of a different kind - working within nature's limits not against them, ramping up the scale of biodiversity reserves on land and "no take zones" at sea to help restore our chronically depleted fisheries.

A proper price should be put on services that nature provides for us - climate regulation, flood control, building fertility in the soil and prioritising efforts to protect endangered species and habitats.

But that does not mean the end of economic progress.

The money required to do these things is a few billion dollars a year - a fraction of the rescue package put together recently to bail out the world's banks.

Scientists have identified biodiversity hotspots around the world that need the most urgent protection.

But each country also has to look in its own backyard. In the UK, much of the diverse flora and fauna is still at risk through intensive farming, new developments, inadequately funded protection schemes and so on.

If this government really wants to be "the greenest government ever", this should be priority number one.

Professor Jonathan Baillie - director of conservation programmes at the Zoological Society of London

Mammal, bird, reptile, amphibian and fish populations have declined by 30% over the past four decades.

Jonathan Baillie believes there is not much room left for the species we share the planet with

Current extinction rates are about 1,000 times higher then the average in the fossil record and, by 2020, at least 25% of the species on this planet are set to be lost.

We are threatening entire ecosystems we depend on for our very survival.

We still plunder forests and oceans with little understanding of what impact this will have on their ability to regulate our climate, provide oxygen or generate food.

The global human population was 3bn in 1960 and will be roughly 9bn by 2050. The global GDP was roughly £10tn in 1960 and estimated to be £100tn in 2050.

Put simply, we are not leaving much room or habitat for the 6-30 million species we share the planet with.

And there is the challenge of global warming.

Increased levels of CO2 result in oceans becoming more acidic, the temperature warmer and weather much less predictable.

This combination of increasing pressure on the Earth while reducing its ability to provide sets up the greatest challenge humanity has ever faced.

So far, the conservation and scientific communities have not effectively made the case that biodiversity is something everyone should care about.

Arguments must be strengthened on why it is important. We will only be successful at conserving biodiversity if it is truly valued.

Conservationists have been effective at addressing environmental issues such as cleaning up the Thames or stopping acid rain but threats to biodiversity are growing exponentially and they simply do not have the capacity to respond.

If we are to make progress, the concept of environmental sustainability must be put in the mainstream and result in solutions to growing challenges coming from all sectors of society.

Politicians will only take a real interest in biodiversity when it is a priority for the majority of people.

We need people to vote for politicians willing to talk about family planning and how we can prosper in a zero growth economy.

Chris Knight - associate director of PriceWaterhouseCoopers with responsibility for forests and ecosystems

In many ways, the last 10,000 years have seen us act as if nature is having a clearance sale, at rock bottom prices.

Chris Knight believes that NGOs and governments cannot deal with biodiversity problems alone

The reality now is that the sale must end soon, before we are out of stock.

Economic studies show we may be losing natural asset values each year equivalent to the combined GDP of India, Russia and Brazil.

While the private sector is often seen as part of the problem, business actually has a vested interest and a role to play in maintaining healthy, functioning ecosystems.

Already 50% of CEOs in Africa and Asia say they are concerned about biodiversity loss threatening their business growth.

But without real incentive, current responses to climate change demonstrate that human behaviours may not change at the speed needed to reduce the threat to biodiversity and ecosystems.

The evidence is clear- NGOs and governments cannot deal with the scale of the problem alone. If companies are clear on what societal goods they need to deliver - food, carbon sinks, freshwater, biodiversity - they will adapt and do it at scale.

Treating natural habitats as valuable long term assets means making far better use of existing land and creating an economic model which rewards farmers, companies and communities for protecting nature.

New global institutions, intelligent regulation and pragmatic approaches to conservation will help us balance human development and the maintenance of life support systems.

With regulatory certainty, flexibility and incentives, the private sector can deliver. In the 1990s, the US laid down regulation to stop the loss of wetland habitat, but gave business flexibility in how it met that.

There is now a $3bn industry in restoring native vegetation and endangered species habitat for profit - if losses are unavoidable in one state then wetland is restored elsewhere.

We need to think differently about the role of business: giving nature a value will allow markets to evolve to protect it.

This is one of a series of reports on biodiversity on The World Tonight , which broadcasts weekdays on BBC Radio 4 at 2200 BST. Listen again on BBC iPlayer.